A first-of-a-kind project underway outside Portland, Oregon, could provide a model for data centers to connect to the grid without driving up utility bills and carbon emissions.

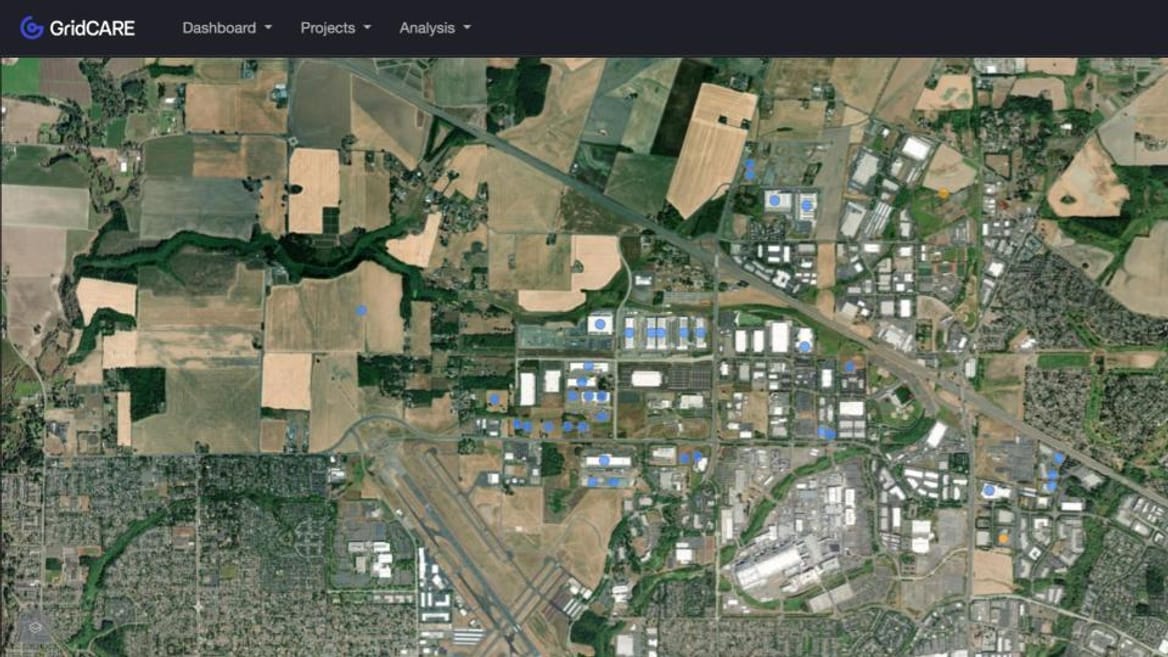

Silicon Valley startup Gridcare launched in May with a promise that its artificial intelligence–powered software can help actualize one of the hottest concepts in the electricity sector: data center flexibility. Last month, it announced the successful use of its software by utility Portland General Electric (PGE) to bring 80 megawatts of data center load online next year in Hillsboro, Oregon.

That’s not a ton of new computing load, considering the gigawatts’ of prospective data center expansions being planned across the country. But as a real-world example of a utility planning around a data center’s commitment to reduce power use during moments of high demand, the project may well be a breakthrough.

“We’ve moved from the theoretical to the practical,” said Larry Bekkedahl, Portland General Electric’s senior vice president of strategy and advanced energy delivery. “This is our first project where that flexibility really comes into play.”

Around the country, utilities are planning massive investments in fossil-fired power plants and grid capacity because of the boom in power demand from data centers. Those spending plans threaten to impose enormous costs on utility customers already struggling to keep up with rising electricity rates.

Data center flexibility agreements could be an elegant solution. If the facilities can ease off their massive power use during the handful of hours per year that they would otherwise overload the grid, they should be able to get connected to the grid sooner — and utilities could defer costly infrastructure upgrades that in some cases include more fossil-fuel power plants.

Other data centers are testing the use of batteries or flexible computing or a combination of both to reduce the burden placed on the grid. But public announcements of flexibility agreements between utilities and data center developers are few and far between — and the technologies that could allow them to become more common are still emerging.

Amit Narayan, Gridcare’s CEO and co-founder, believes PGE’s use of his company’s software may be the “first project of its kind where a utility has been able to accelerate data center expansion at this scale.”

Narayan said the startup also has projects underway with unnamed tech giants and data center developers, as well as with utilities including California’s Pacific Gas & Electric.

“We have these new tools of real-time visibility and dispatchability and control of distributed energy technologies,” Narayan said. “Why do we have to live with the old assumptions of designing around worst-case scenarios?”

In order to understand how PGE and Gridcare’s approach differs from that of other data center flexibility projects around the country, it’s important to grasp the complexity of the problem PGE is trying to solve for its Hillsboro data center cluster.

Hillsboro, a major hub for chipmaker Intel and a terminus for multiple fiber-optic cables connected to Asia, is experiencing “huge demand for data centers in the 50-megawatt to 500-megawatt range,” PGE’s Bekkedahl said. Those data centers are powered by the utility’s transmission grid, which is structured as a network that shares power across multiple interconnected nodes. And existing electricity demand is already pushing that grid close to its operating limits in the Hillsboro area.

Data centers seeking more power from that constrained grid have put PGE in a bind, he said. Under traditional utility planning, the network would have to be scaled up to provide enough power to serve every customer during times of peak demand.

“But there are only a few peak hours, during maybe five to 10 days a year, that we need to meet those peaks,” he said. Building enough transmission to serve them all would take years, cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and yield a grid that’s far bigger than what’s needed most of the time.

Flexibility projects aim to prevent the need to overbuild by reducing the demand peaks that new data centers cause. But PGE can’t make plans based on what a single data center might do. It has to consider the growth plans of all the customers connected to that part of the grid, during every hour of the year, for years into the future — and then also consider the impact on PGE’s regional transmission network and generation fleet.

Human grid planners simply can’t parse through all those variables at once, Bekkedahl said, even with the help of standard planning software.

“That’s where Gridcare came in and helped us model,” he said. Through Gridcare’s software, PGE identified a combination of flexibility opportunities that could allow data centers to add 80 megawatts of additional power use next year, instead of waiting years for traditional grid upgrades, he said.

Narayan is familiar with complex computing challenges. He founded, built, and sold a semiconductor design company called Berkeley Design Automation in the 2000s. Next, he launched Autogrid, a “virtual power plant” software provider that was sold to Schneider Electric, the French energy equipment and services giant, in 2022 and is now part of utility software company Uplight.

Gridcare applies similar computing techniques to model the interactions of lots of power-hungry customers across a dynamic, networked grid, he said.

“You have a major combinatorial-explosion issue here,” Narayan said. “Instead of analyzing one case and one dispatch scenario, which planning teams do — and which is itself very complicated — you have to analyze 200,000-plus scenarios and contingencies.”

Under traditional grid-modeling methods, “that’s typically done in a sequential way, one project and one scenario at a time,” he said. But that’s a highly impractical approach to finding solutions quickly enough to inform utility decision-making.

As Narayan noted, “We have to look at many different projects, each with its impact on ramp and load, over the next five to 10 years. We have to look at very many different scenarios of flexibility. And we have to do it for every hour of the year.”

Recent developments in AI and computing power have made this complex problem solvable: “We’re able to take all the sources of flexibility that may exist, and then examine all the combinations and permutations that exist, and find the lowest-cost way to manage those constraints.”

Not all utilities are ready to rely on flexibility as an alternative to hard grid upgrades. But PGE has been working for years on modernizing its grid operations to support distributed energy and flexibility and bring in real-time data from AI-enabled smart meters, which has given its grid operators confidence in understanding and managing customer-sited energy resources, Bekkedahl said.

With that expertise to back up Gridcare’s revelation of the options at hand, PGE has been able to approach data centers in the Hillsboro area to propose mutually beneficial commitments, he said.

“Those data centers that are willing to work with us, if they’re willing to be flexible, we’ll put them at the top of the queue” for additional power, Bekkedahl said. “For someone who says, ‘Nope, we’re going to want 100 percent,’ well then, we say, ‘You’ll wait for us to build the transmission.’”

At least one data center has already pulled the trigger on a project identified by the collaboration between Gridcare and PGE. Last month, Aligned Data Centers announced plans to work with energy-storage specialist Calibrant Energy to deploy a 31-megawatt/62-megawatt-hour battery across the street from its Hillsboro data center. It’s the first publicly revealed project that’s part of the scope of work enabling the 80 megawatts of additional capacity that PGE will be able to energize next year.

Once it’s turned on sometime next year, that battery will allow Aligned to expand its computing capacity at the data center years faster than it would have been able to by waiting for PGE to upgrade its grid to supply its peak power demand. Aligned didn’t disclose how many megawatts of increased power demand its expansion will cause, a sign of the highly competitive nature of today’s data center market.

Accelerating that “speed to power” has become an overweening obsession of data center operators seeking to meet tech giants’ AI ambitions, and flexibility is increasingly pointed to as the way forward.

A February report from a Duke University team led by researcher Tyler Norris found that the U.S. has nearly 100 gigawatts of existing capacity for data centers that can curtail less than half of their total power use during peak demand events, which occur about 100 hours of the year. Last month, Energy Secretary Chris Wright ordered the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to fast-track a rulemaking process to prioritize such flexible interconnections on U.S. transmission grids.

But data centers can’t afford to invest in batteries like this without clear commitments from utilities that those investments will in fact resolve the grid constraints preventing them from getting online faster.

“This is where PGE was a fantastic partner with us,” said Michael Welch, Aligned’s CTO. “They were able to model these scenarios and understand them with a high degree of accuracy, and provide the greatest impact without wasting capacity. As that came into clarity for us, we were able to work within those constraints.”

Bekkedahl emphasized that PGE is taking its time in its work with Gridcare. While the utility hopes to interconnect 400 megawatts of expanded data center load in Hillsboro by 2029, “we’re not putting on 400 megawatts tomorrow,” he said. “There’s a stepping-stone process here. We want to see it in action before we believe it.”

Nor can PGE completely avoid building more transmission and generation to meet its fast-growing demand for power. “We’re going to have to build out. This is just a bridging strategy,” he said.

But any approach that can increase the amount of electricity that PGE sells without adding exorbitant grid costs should help reduce the impact on customers at large, Bekkedahl said. “Bringing down the peak, and bringing up the overall utilization of the system, makes it more affordable for all customers.”