See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

It’s official: Grid batteries broke another record.

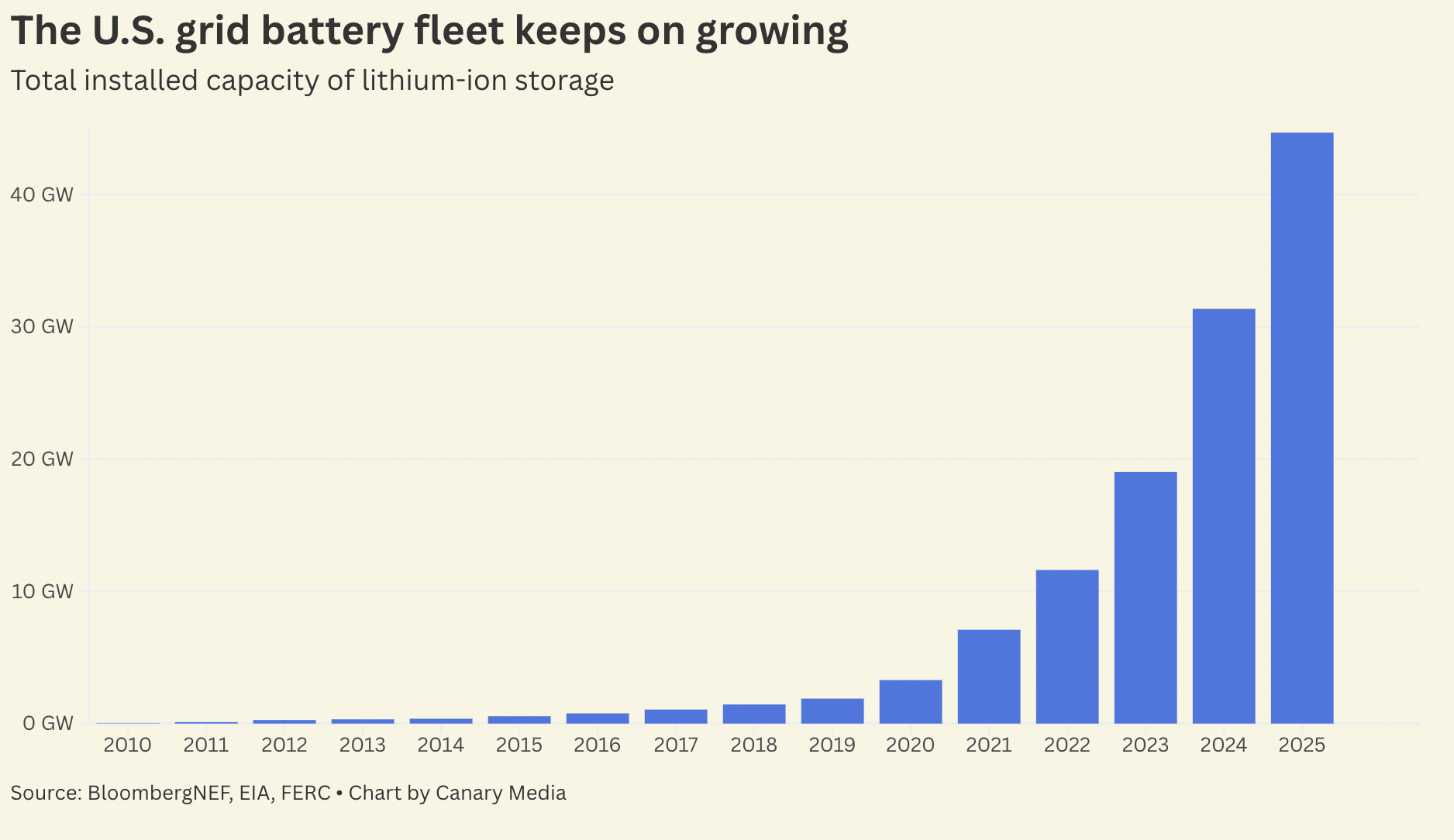

More than 13 gigawatts of energy storage was installed across the U.S. last year, per a new report from the Business Council for Sustainable Energy and BloombergNEF. That’s up from the roughly 12 GW installed in 2024.

It’s the latest reminder of the meteoric rise of battery storage, a quick-to-deploy technology that’s key to cutting emissions from the electricity system. Storage enables the grid to bank electricity when it’s cheap and abundant — like when surplus solar is generated in the middle of a sunny day — and deploy it when prices are high and electrons are scarce.

Less than a decade ago, the sector was little more than an intriguing possibility. Energy storage in America mostly meant massive, decades-old pumped-hydro storage projects and a handful of small lithium-ion battery plants.

In 2017, only 500 megawatts of grid battery capacity was online in the U.S.; now, there are individual battery installations larger than 500 MW. Still, the sector had big expectations for itself back then: In 2017, the Energy Storage Association set a goal of reaching 35 GW of storage capacity by 2025.

Last year, the sector smashed that goal, hitting it in July and ending the year with nearly 45 GW of installed capacity.

Increasingly abundant solar power, rising energy demand, and declining battery costs have combined to propel the storage sector to these lofty heights. To date, most utility-scale batteries have been plugged into the grids of Texas and California, two solar-soaked states with radically different approaches to encouraging storage growth.

In the coming years, the storage sector has a smoother path to continued growth than do renewables.

Yes, it faces some challenges. Federal tax incentives are now contingent on compliance with strict but vague anti-China supply-chain rules. Developers also have to deal with tariffs and increasing local opposition.

But, unlike for solar and wind, tax credits for storage were spared in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act that President Donald Trump signed into law in July. Also unlike solar and wind, the battery industry has not yet attracted much explicit trash-talking from either Trump administration officials or Trump himself. Storage is also increasingly cheap and fast to build.

These facts, plus the urgent need for new sources of affordable energy as utility bills rise, have the storage industry poised for continued growth in the years to come.

This analysis and news roundup come from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

President Donald Trump has all but dismantled U.S. efforts to curb pollution that’s warming the planet and harming human health.

Yet with every federal blow to climate action, states have launched a counterpunch. Take Colorado: After Trump and congressional Republicans ended federal EV tax credits, the state juiced its own clean-car incentives. California has meanwhile inked a deal with the United Kingdom to cooperate on clean energy and climate efforts. And several other states are considering “climate superfund” laws, which seek to hold fossil fuel companies financially responsible for climate change–induced damages.

But instead of doubling down on decarbonization in this critical hour, and despite touting that it has one of the most ambitious climate laws in the country, New York is quietly backing away from its efforts.

The most recent and symbolically loaded move concerns that very same climate law, the 2019 Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. New York’s utility regulator is currently considering suspending its marquee clean-energy goal, which requires the state to get 70% of its power from renewables by 2030 and 100% by 2040.

To be clear, New York is not on track to meet this target anyway. But behind the proposed rollback is a petition, signed by two natural gas company veterans, which claims that the target will jeopardize grid reliability, Gothamist reports. New York’s grid operator has cautioned that power shortfalls are a mounting risk, but environmental advocates point out that the warning doesn’t take a ton of soon-to-connect clean energy projects into account. That includes two offshore wind projects that have been slowed by the Trump administration.

It’s just the latest climate retreat by Gov. Kathy Hochul, a Democrat who is up for reelection this year.

Last year, New York was poised to implement a first-of-its-kind ban on fossil-fueled heating and appliances in new homes and buildings. But in November, just before the rule was set to take effect, the state said it wouldn’t enforce the regulation while a lawsuit continued to play out.

Hochul has also repeatedly delayed the implementation of the cap-and-invest program that’s essential to New York’s emissions goals, leaving what could be billions of dollars for renewables construction and energy-efficiency projects in limbo.

And while Hochul has called for more clean energy and nuclear power to meet rising demand, she has also signaled natural gas is essential to the state’s energy strategy, as she allowed a previously rejected pipeline to move forward.

Hochul’s motive for most of these moves has been clear: She’s worried about rising power prices in the state and has cited a need to “govern in reality” amid the federal government’s clean energy assault. But as a warming climate puts New York and the rest of the world increasingly at risk, running in the wrong direction on decarbonization is anything but governing in reality.

What the endangerment finding rollback means for automakers

The EPA last week revoked the endangerment finding, which underpins the U.S. government’s authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. This rollback has upended federal tailpipe emissions regulations, which the administration says will curb vehicle prices and save Americans as much as $1.3 trillion by 2055.

But the EPA’s own analysis tells a different story, The Guardian reports. It estimates Americans will rack up more than $1.4 trillion as they buy more fuel, need more repairs, and face increased traffic and noise — essentially negating those touted savings.

And it’s unlikely that U.S. automakers will backtrack on vehicle efficiency like the EPA wants, experts tell The New York Times. The rest of the world is still moving toward electric vehicles, so cars that use more gasoline are the opposite of what other countries — and many Americans — will buy.

Fake public comments are clean energy’s latest threat

As if clean energy didn’t have enough challenges to deal with.

Last June, Southern California’s top air-quality authority rejected a plan that would have pushed the region away from gas appliances. Regulators received tens of thousands of comments opposing the plan, but a Los Angeles Times investigation found at least 20,000 of them appear to have been AI-generated. The agency’s staffers also reached out to some alleged commenters, and at least three said they hadn’t written a comment.

The incident is similar to what Canary Media’s Kathiann M. Kowalski reported on earlier this month. In Ohio, state regulators may reject a solar farm that received dozens of public comments opposing it. But as the project’s developer found, and Kowalski verified, more than 30 of those commenters appear to have used fake names or lied about living in the county where the solar farm will be built.

Another coal-plant prop-up: Documents indicate that the Trump administration will move to let coal plants emit more hazardous pollutants, including mercury, in an attempt to juice the industry. (New York Times)

Chillin’ with Duke Energy: Canary reporter Elizabeth Ouzts let North Carolina utility Duke Energy remotely lower her thermostat in exchange for bill credits, and even in a recent cold spell, Ouzts says she found the savings meaningful. (Canary Media)

Illinois’ nuclear reversal: Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker (D) calls for the state to build at least 2 gigawatts of nuclear capacity, just a month after lifting the state’s long-standing moratorium on nuclear construction. (Bloomberg)

Cancer Alley’s new threat: Louisiana residents already saturated with petrochemical pollution now face a wave of “blue ammonia” plants, which will burn fossil fuels and potentially saddle them with even more emissions. (Floodlight)

Power surge: 2025 was a tough year for clean energy in the U.S., but grid batteries still set another installation record as more solar power came online and power demand rose. (Canary Media)

Heat pumps can save households money on their utility bills and are essential to cutting carbon emissions. The catch? The superefficient appliance can cost thousands of dollars more than a new gas furnace.

Zero Homes aims to change that. The startup just raised $16.8 million to make it cheaper and easier for homeowners to switch to heat pumps.

Founded in 2022, the Denver-based company can scope and size the all-electric systems without ever stepping foot inside a customer’s home. Its digital platform cuts the cost of a heat pump installation by 20% on average, with much greater savings common in hard-to-reach rural areas, according to Grant Gunnison, Zero Homes’ founder and CEO.

Prelude Ventures led the Series A funding round. “Homeowners want comfort, and they want it easy,” Matt Eggers, Prelude’s managing director, said in a statement. “Zero Homes has built the missing digital infrastructure for home upgrades, making it dramatically easier for millions of homeowners to adopt efficient, modern systems without friction.”

The first step in getting a heat pump is sizing: figuring out how big a system needs to be to efficiently and comfortably heat and cool a home. It’s crucial to get that right. A wrong-size system can lead to worse comfort, bigger energy bills, a shorter appliance lifespan, and a greater risk of health-harming black mold.

Historically, quoting a heat pump system’s size has been a hands-on job. Most heat pump installers visit a home to conduct what’s called a Manual J assessment: the gold standard method to determine how much heating and cooling a building requires to keep occupants comfortable. An in-person visit adds time and expense before customers have even committed to a project. And that, according to Gunnison, unnecessarily inflates heat pump costs.

Reducing those “soft costs” is especially important now, as utility bills rise nationwide. Electricity and piped gas prices are the biggest drivers of overall inflation.

The startup aims to cut project costs by eliminating the need for an in-person Manual J step with software. By using the company’s free phone app, an individual can take photos and videos of their home and receive a heat pump quote, with all applicable rebates and tax credits included. Once a homeowner agrees to the price, Zero Homes schedules a vetted contractor to get the system up and running.

Beyond reducing costs, this has the added benefit of being less disruptive to customers than the traditional, on-site procedure, which requires a homeowner to coordinate with an HVAC contractor.

“We want to … be nationwide,” said Gunnison, a former general contractor and an MIT-trained engineer who once worked on satellite communications and remote imaging at NASA.

To achieve that scale, Zero Homes relies on partnerships with independent installers that it subcontracts with. Currently, the company operates in Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Illinois, and California.

Zero Homes’ approach has gained some traction. The U.S. Department of Energy validated the startup’s remote assessments in 2024, Gunnison reported. The Air Conditioning Contractors of America also that year approved the startup’s software as a tool to perform the organization’s trademark Manual J calculations remotely.

Gunnison declined to share whether the company was profitable, but he did say that its revenue had grown by a factor of 10 from 2024 to 2025. Customer service calls on the installations it has managed are “very low,” he added. And Zero Homes’ installer network has expanded to nearly 100 contractor businesses.

“We get rid of a lot of the overhead that costs them a lot of time and heartache, so that they can be successful,” Gunnison noted. “We don’t charge them for leads; [we] fill their calendars.”

A number of utilities and power co-ops, including ComEd, Great River Energy, and Tri-State Generation and Transmission Association, have hired Zero Homes to deploy heat pumps in their service territories. A couple of local governments have also expressed confidence in the company: Chicago partnered with Zero Homes as part of its Green Homes program, and Colorado is giving the business a $745,000 boost through its economic development office to expand its Denver-area operations.

Several other startups around the country are specializing in heat pump installations, such as Elephant Energy, Tetra, Forge, Quilt, and Jetson — which recently raised $50 million to get its in-house-designed heat pump into more buildings.

Gunnison plans to use the new infusion of capital to double his company’s 25-person headcount this year and improve its software capabilities, he said.

It used to take Zero Homes several days to provide a quote to a homeowner who had submitted a scan. Now that process is complete in about one day. By the end of 2026, the startup aims to slash that time to 30 minutes, Gunnison noted.

“Once we can consistently deliver that, then we will very, very rapidly expand geographically.”

Before temperatures plunged to the teens in the wee hours of Feb. 2 in North Carolina, Duke Energy pleaded with customers like me to conserve.

Since electricity supplies would be strained, the utility said in a blanket email, we could help avoid planned blackouts by lowering our thermostats and perhaps putting on a sweater. I got a text, too, asking me to cut back on “nonessential energy use.” In other words: Embrace my inner Jimmy Carter.

The missives worked, in that Duke didn’t have to schedule outages around the state, but they also provoked resentment. At public hearings, some complained that large customers like data centers probably didn’t get the same appeal. On social media, I saw at least one energy policy wonk contend that the utility should be paying customers — not just asking them nicely — to reduce their energy use.

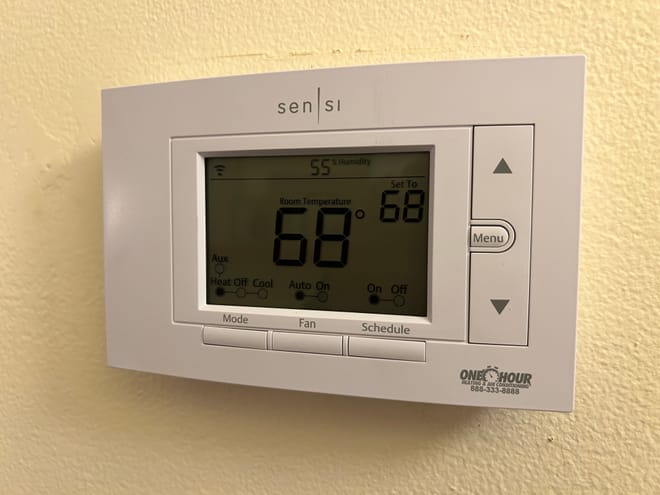

But it turns out that Duke also does that. I should know: Late last year, I joined the throng of Tar Heels who let the company remotely adjust our smart thermostats by a few degrees when needed in exchange for a credit on our bills. It’s just one example of the sort of demand-response program that clean energy advocates say should be expanded not just in North Carolina but also nationwide, as climate change leads to more frequent extreme weather that taxes electricity supplies.

While broad solicitations like the one I received on Feb. 1 can help relieve stress on the grid when every watt counts, paying customers to enroll in ongoing programs can have a more substantial effect. Plus, they offer some much-needed utility-bill relief for households dealing with skyrocketing energy costs in North Carolina and beyond.

A version of the incentive program I participate in has been around for nearly two decades, after a 2007 law required Duke to invest more in energy efficiency. Long an option in the summer for those with central air conditioning, the scheme was recently extended into the winter. Around 500,000 customers are enrolled in the warm months, Duke says, and some 66,000 are signed up in the cold months. (Participation is lower in the winter partly because many customers heat their homes with gas rather than electricity, per the utility.)

Duke hasn’t yet analyzed the precise effectiveness of this one residential incentive program during this year’s unusually frigid temperatures. But it says the combination of this household initiative, similar ones for business customers, and the mass conservation request all made a difference.

“The collective efforts of customers in our demand response programs and those who voluntarily reduced their energy use made a substantial impact during the stretch of extreme cold and unusually high energy demand,” spokesperson Jeff Brooks said in an email. “Across our Carolinas service areas, customers helped reduce demand on the grid by contributing hundreds of megawatts of electric load reduction.”

Hundreds of megawatts is no small matter. It’s the equivalent of the grid getting an additional small gas-fired power plant — but without the associated pollution or cost.

For consumers, there were clear upsides, too.

In Raleigh, where I live, the scheme is called EnergyWise. In other parts of Duke’s territory, it’s called Power Manager. Everywhere, the idea is the same: Customers with electric heat and thermostats connected to the internet get a $150 credit for enrolling, then $50 a year after that, plus whatever money we save by using a little less heat than we might otherwise. It’s not a staggering amount, but since the average Duke household in North Carolina spends about $154 a month on electricity, it’s not nothing, either.

For my part, the savings have been meaningful. I live in a small house powered partly by solar panels, so I’m not a prototypical Duke customer. But since joining the program in early December, I’ve paid the utility all of $6.45, thanks to the sign-up incentive. (My bill due in March, to be fair, is close to $130.) With Duke proposing rate increases of 15% in the coming years — and a 2025 law requiring households to shoulder more of the burden when the company buys power from outside the state — I’ll take the extra dollars where I can.

“Active savings events,” whereby Duke lowers my temperature setting a few degrees for one or two hours, happen a few times a month, per the company, or not at all if the weather is mild. A message on my physical thermostat, and on the phone app that controls it, tells me when an event is underway. I can opt out at any time by changing the temperature as I see fit.

A Gen Xer, I grew up in a household where only one person — my father, born in the throes of the Great Depression — could control the thermostat. His rule was kind but firm, with winter settings that never exceeded the high 60s. Sometimes he would cheerfully encourage an extra layer and start a fire. At night, he always set the temperature much lower.

Perhaps that upbringing, together with my career as an energy reporter, explain why I’ve felt the need to override a savings event only once so far. It wasn’t to raise the temperature but to lower it during the recent cold snap: I woke up in the middle of the night and realized I’d accidentally set the thermostat higher than normal. While Duke’s system had adjusted the heat down a few degrees, I wanted it to be colder still — a little bit for the planet, a little bit for bedtime coziness, but mostly for my wallet.

Of course, plenty of people will balk at giving Duke — a monopoly that almost by definition breeds distrust — control over their thermostats. And I can surely see how the entreaty for households to voluntarily conserve left a bitter taste when the company was reporting sky-high profits.

But I suspect there are scores of people like me, who are happy to do their part and save a little money at the same time with basically no risk. As for the half million North Carolinians already enrolled in the program, I know one thing for sure: They aren’t all energy reporters with solar panels.

A correction was made on Feb. 19, 2026: This story originally misstated the date of the Duke Energy email as Feb. 2; it came on Feb. 1.

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist’s weekly newsletter.

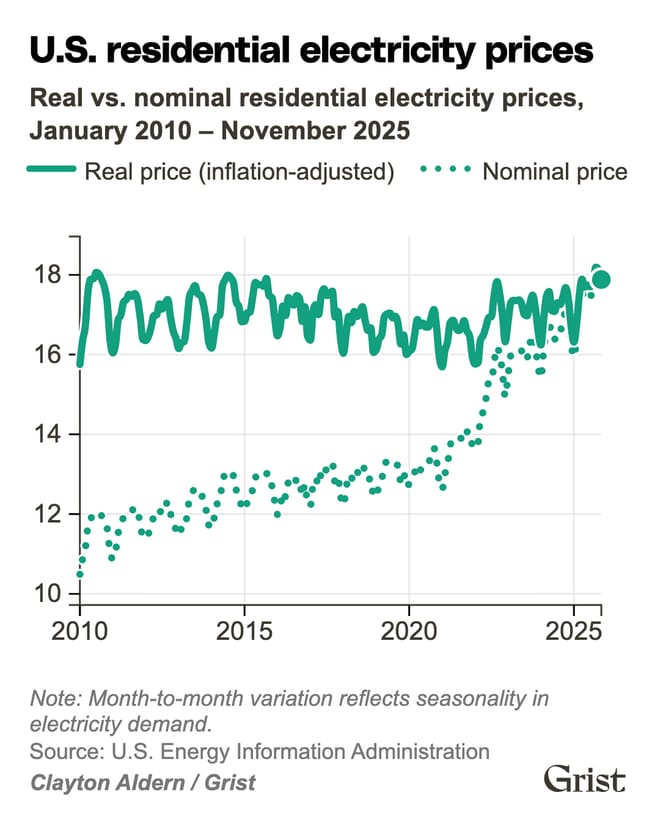

It’s no secret that U.S. electricity prices have been rising over the last few years: The average residential energy bill in 2025 was roughly 30 percent higher than in 2021. This jump is largely in line with the overall inflation Americans have experienced during this period. As the cost of groceries, gas, and housing has increased, so too has the cost of electricity.

But there are big differences from state to state and region to region. Some places — like California and the Northeast — have seen mammoth price increases that outpaced inflation, while costs have held steady in other parts of the country, or even fallen in relative terms. Nearly everywhere, though, rising electricity costs have strained the budgets of low-income households in particular, since they spend a much larger share of their earnings on energy, compared with wealthier Americans.

Higher energy bills have also become a political flashpoint. Over the past year, rising electricity prices have helped push voters to the polls, and politicians have taken note. In Virginia and New Jersey, newly elected governors campaigned heavily on reining in utility bills. In Georgia, incumbent utility regulators were booted out by voters, who elected two Democrats to the positions for the first time in two decades.

A wide range of culprits have been blamed for the surge in electricity prices, with energy-hungry data centers shouldering much of the criticism. Tariffs, aging power plants, and renewable energy mandates have also come under fire. But the reality is far more nuanced, according to recent research from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the latest price data from the federal government’s Energy Information Administration. Electricity prices are shaped by a complex mix of factors, including how utilities are structured, how regulators oversee them, regional divergences in fuel prices, and how often the grid is stressed by heat waves or cold snaps. In many states, the biggest driver is the rising cost of maintaining and upgrading grids to survive more extreme weather — the unglamorous work of replacing old poles and wires.

But the forces driving high bills in California aren’t the same as those affecting households in Connecticut or Arizona. In this piece, we highlight one key driver of recent price trends in each region of the country. (The regions below are organized alphabetically, with individual entries for Alaska, California, Hawaiʻi, the Midwest, the Northeast, the Pacific Northwest, the Southeast/Mid-Atlantic, the Southwest/Mountain West, and Texas.) While the dynamics of every utility bill are different — including those within the same state — recent data demonstrates the many challenges ahead as public officials promise a laser focus on energy affordability.

Key factor: Geographic isolation

Alaska’s electricity prices are among the highest in the country, largely because the state’s power grid operates in isolation. Unlike utilities in the lower 48 states, Alaska’s providers can’t import electricity from neighboring states or Canada when demand spikes or supply runs short. That isolation limits flexibility and drives up costs. Utilities also have to spread the expense of generating and transmitting power across a relatively small customer base. The state’s primary grid, known as the Railbelt, serves about 75 percent of Alaska’s population. Beyond it, more than 200 microgrids power rural communities, many of which rely heavily on diesel generators. These structural challenges contribute to electricity rates that are roughly 40 percent higher than the national average.

Electricity prices have been rising in the state over the past decade, even after adjusting for overall inflation. A study by researchers at the Alaska Center for Energy and Power found that residential rates for Railbelt customers increased by about 23 percent between 2011 and 2019. Rural customers saw a roughly 9 percent increase during the same period.

While more recent data charting electricity prices adjusted for inflation isn’t readily available, energy costs are likely to grow in the state. That’s because Alaska depends on natural gas for electricity generation and heating, and it relies on the Cook Inlet basin for natural gas. With supplies dwindling in that reserve, the state is expected to face a shortage soon. If it chooses to import natural gas, it will be much more easily affected by price swings in the natural gas market. State regulators have also approved a 7.4 percent interim rate increase for the Golden Valley Electric Association, the primary utility that serves the Fairbanks area. A full rate case review is underway, and a final decision on the rate will be made in early 2027.

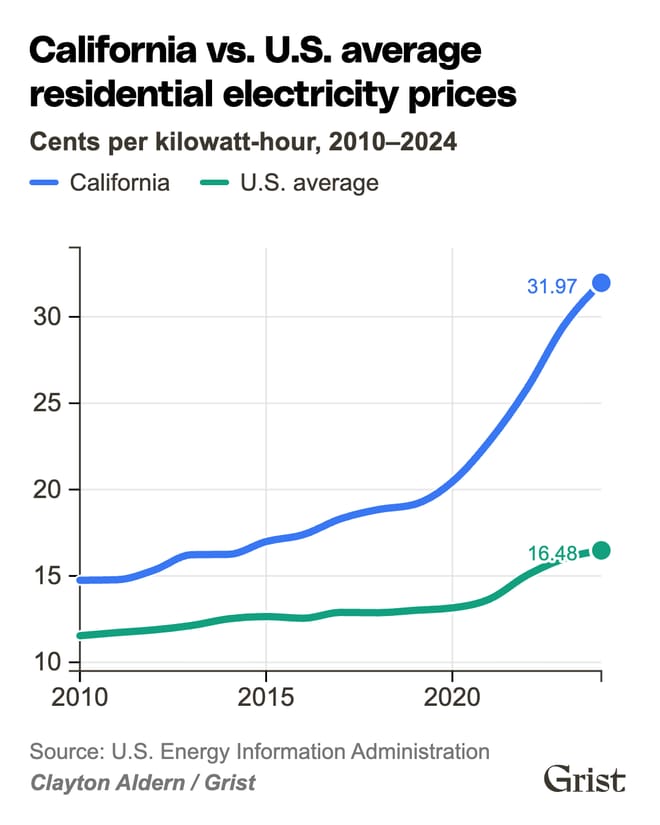

Key factor: Wildfires

Californians have long paid above-average electricity prices. Since the 1980s, rates in the Golden State have typically been at least 10 percent higher than the national average. For decades, however, those higher per-kilowatt-hour prices were largely offset by lower electricity use as a result of the state’s relatively temperate climate. In other words, electricity in California cost more per unit, but residents consumed far less than households in many other states, keeping average monthly bills relatively low. That began to shift in the mid-2010s when the state began experiencing more frequent and larger wildfires. Since then, electricity prices have outpaced consumption, leading to exorbitantly high energy bills.

Between 2019 and 2024, California had the largest increase in retail electricity prices of all U.S. states. Monthly energy bills in 2024 averaged $160, roughly 13 percent higher than the national average. Much of that increase has been driven by the soaring cost of infrastructure upgrades aimed at reducing wildfire risk, along with rising wildfire-related insurance and liability costs. After the 2018 Camp Fire, PG&E declared bankruptcy, citing $30 billion in estimated liabilities. Utilities have also poured billions of dollars into replacing aging transmission and distribution lines and expanding the grid to meet growing demand.

California’s high rate of rooftop solar adoption has also played a complicated role in rising prices. As more customers install rooftop solar, they purchase less electricity from the grid. That leaves utilities with the same fixed infrastructure costs — but fewer kilowatt-hours over which to spread them. The result: higher per-unit rates for customers who remain more dependent on grid power. Since renters and low-income Californians are less likely to benefit from residential solar, rising electricity rates hit them harder.

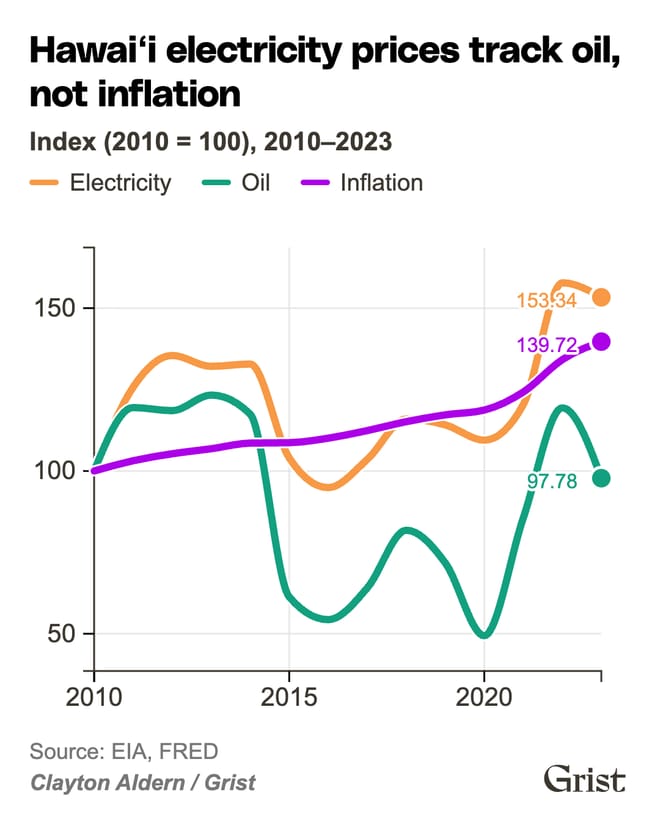

Key factor: Oil dependence

Hawaiʻi has the highest electricity bills in the country. Average residential rates rose by about 8 percent between 2019 and 2024, even after adjusting for overall inflation, and the typical household now pays more than $200 per month for electricity.

Those high costs are rooted in the state’s unique energy system. Hawaiʻi remains heavily dependent on oil to generate power, and many of its oil-fired plants are aging and relatively inefficient. That reliance ties electricity prices directly to global oil markets. Hawaiian Electric, the state’s primary utility, purchases crude oil on the open market and pays to have it refined before it is burned to produce electricity — meaning fluctuations in both crude prices and refining costs show up on customers’ bills.

While oil prices have eased in the past couple of years, they spiked sharply in 2022 following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, driving up fuel costs and, in turn, electricity rates. Refining costs on the islands have also risen in recent years, adding further pressure to household bills. Fuel and equipment must also be shipped thousands of miles from the mainland — and often transported between islands — adding significant logistical costs. Hawaiʻi’s power grids are also small and isolated. Electricity generated on one island cannot easily be transmitted to another, limiting flexibility and preventing the kind of resource sharing common on the continental grid. Together, those structural constraints help keep electricity prices in Hawaiʻi persistently high.

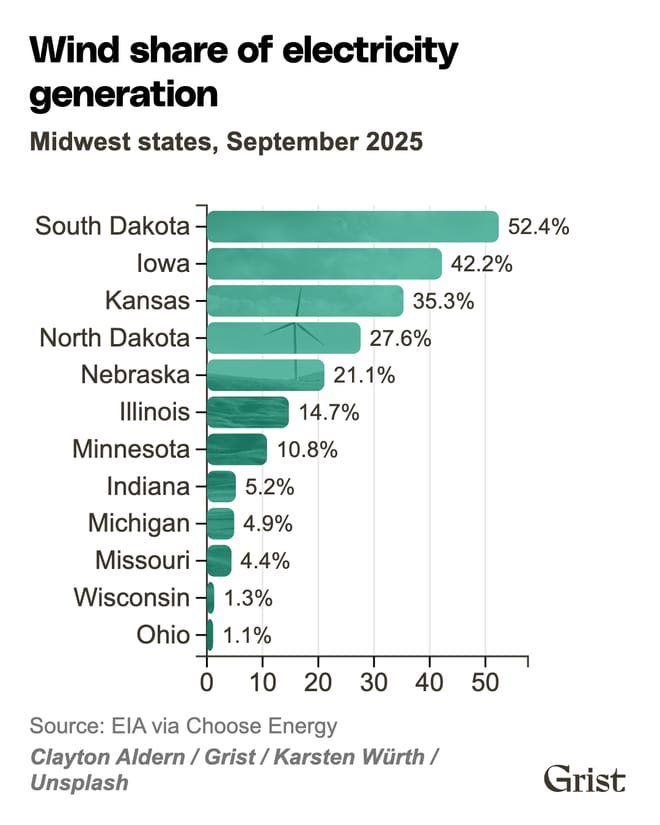

Key factor: Wind energy

The Midwest and Great Plains states saw only modest changes — and sometimes even declines — in inflation-adjusted retail electricity prices per kilowatt-hour between 2019 and 2024. Average monthly electricity bills typically fall between $110 and $130.

This stability is largely a renewable energy success story: Many Midwestern states are now deeply reliant on wind power. Wind supplies more than 40 percent of electricity in Iowa and South Dakota, and more than 35 percent in Kansas. Investments in utility-scale wind and solar have helped shield consumers from price shocks tied to natural gas volatility, since renewables have no fuel costs and can reduce exposure to sudden spikes in gas prices. Research also shows that these investments can lower wholesale electricity prices by displacing higher-cost generation during periods of high wind and solar output.

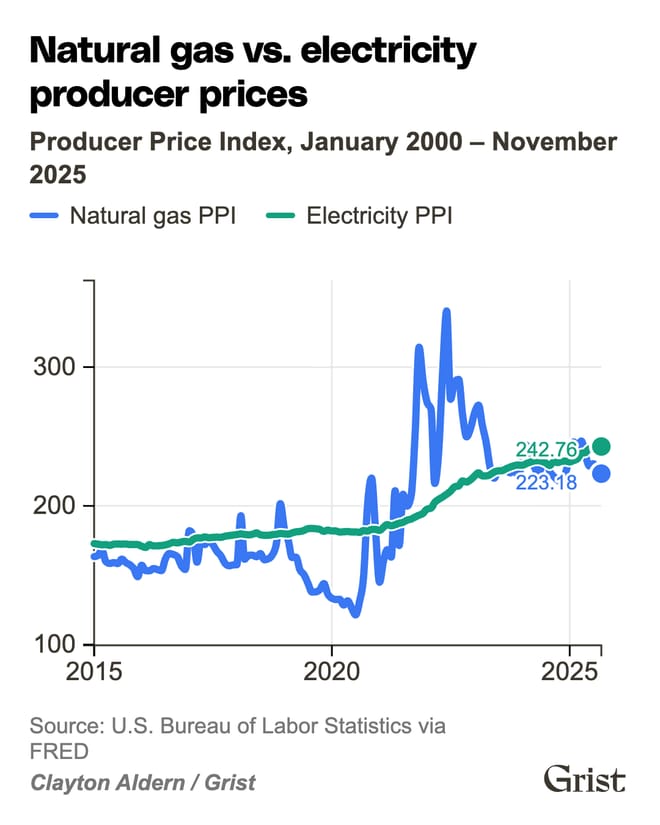

Key factor: Natural gas prices

Aside from California and Hawaiʻi, northeastern states experienced some of the steepest increases in retail prices between 2019 and 2024. Prices in New York and Maine rose by more than 10 percent over the last few years. Connecticut residents pay nearly $200 per month for electricity.

The region’s heavy reliance on natural gas as both a home heating fuel and a source of utility-scale electricity is a major driver of high energy bills, especially in winter. When temperatures drop, demand for natural gas surges as homes and businesses burn more fuel for heating. Power plants are then forced to compete with those heating needs for the same constrained supply. (Gas has to be transported to the region via pipelines that stretch as far as Texas.) With no easy way to bring in additional gas, prices spike, and those increases ripple through to power bills.

A combination of forces has worsened natural gas constraints in recent years, pushing electricity prices even higher, particularly during cold snaps. More households in the region are switching to heat pumps and buying EVs, driving up demand for power. International energy policies, like increasing U.S. exports of liquefied natural gas and the global gas crunch caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, are driving up fuel costs stateside. Utilities in the Northeast, like those elsewhere in the country, are also pouring money into infrastructure upgrades, and those investments are being passed on to customers through higher bills.

Key factor: Hydropower

Retail electricity prices in the Pacific Northwest rose only modestly over the last few years, at least compared with the country’s general rise in the cost of living. Inflation-adjusted prices in Washington and Oregon increased by about 5 percent between 2019 and 2024, while Idaho and Montana saw slight declines. In 2024, average monthly energy bills across the four states ranged from about $105 to $130, roughly in line with the national average. (This is not to say that customers haven’t noticed growing totals on their energy bills; the Energy Information Administration estimated that Oregon’s average retail price increased by 30 percent between 2020 and 2024, which is roughly in line with overall inflation over the last several years.)

So why has the region been largely insulated from the inflation-adjusted cost spikes that have struck neighboring areas like California? Hydropower. Abundant, low-cost hydroelectric generation has long kept energy bills in the Pacific Northwest — and the climate impact of the region’s power generation — among the lowest in the country. And while utilities in these states are facing rising costs tied to wildfire mitigation and infrastructure upgrades, cheap and plentiful hydropower has so far helped offset those increases.

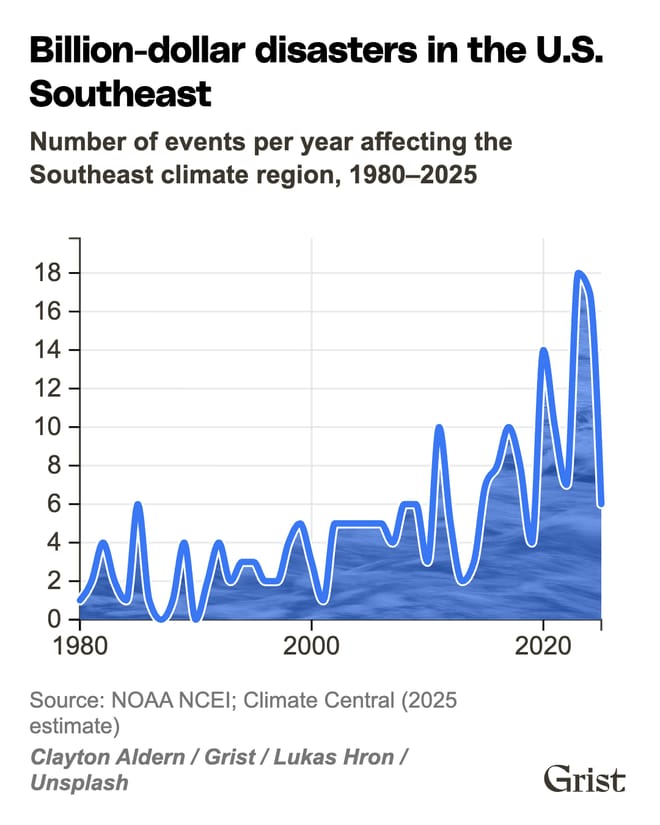

Key factor: Extreme weather

Southeastern states frequently face hurricanes, flooding, and extreme heat. In recent years, the number of billion-dollar disasters in the region has increased, an ominous sign of the havoc that climate change will wreak. Utilities are fronting the costs of both weathering these events and rebuilding in their aftermath — and then they pass them on to their customers.

The cost of distributing electricity — think the power lines that deliver energy to your home — rose significantly in the Southeast over the past few years, driven mostly by capital expenditures to upgrade and build new infrastructure. In Florida, for instance, damage from Hurricanes Debby, Helene, and Milton in 2024 resulted in residential price increases from 9 to 25 percent the following year. Similarly, Entergy Louisiana’s plan to harden its grid costs a whopping $1.9 billion, much of which will be borne by customers through rate increases.

Some states in the region, such as Virginia, have also seen a major influx of data centers, which consume enormous amounts of electricity. In some areas, utilities are upgrading infrastructure to meet that demand, raising concerns that those costs could push electricity prices higher. However, a national study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that an increase in demand in states between 2019 and 2024 actually led to lower electricity prices on average. That’s because when there’s more demand for power, the fixed costs of running a utility — such as maintaining the poles and wires that deliver electricity to your home — are spread out over a greater number of customers, leading to lower individual bills.

In Virginia, the world’s largest data center hub, electricity prices rose only modestly between May 2024 and May 2025, despite a rapid build-out of new facilities. But that dynamic could shift as hyperscalers construct ever-larger campuses. Ultimately, prices will hinge on how utilities and regulators choose to plan and pay for that demand.

For now, however, extreme weather remains one of the region’s main drivers of rising costs.

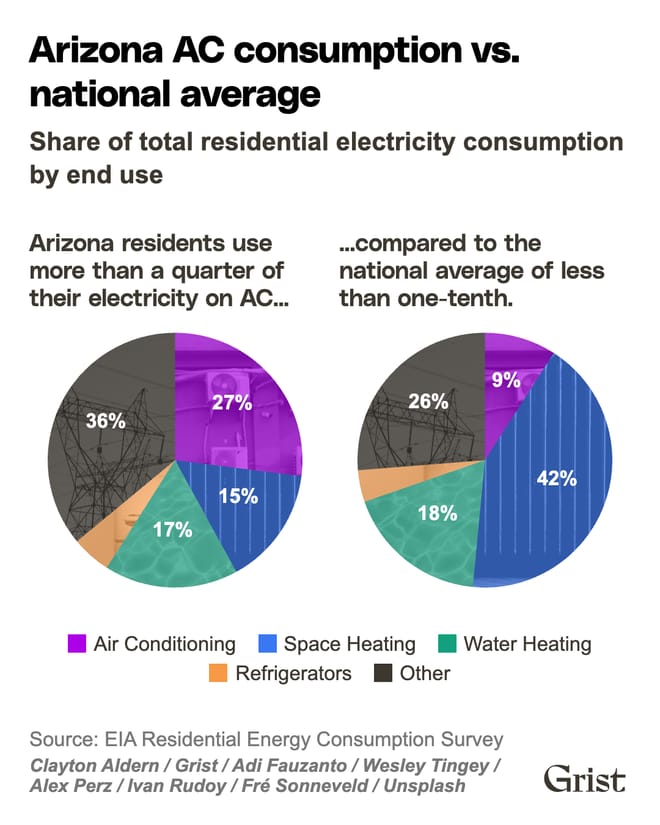

Key factor: Hotter summers

Arizona and New Mexico saw a nominal decrease in retail electricity prices between 2019 and 2024, after adjusting for overall inflation. However, there is a big difference between the states in how much residents pay for energy every month. Energy bills in New Mexico averaged just $90, while in Arizona they were nearly double, at $160.

The main difference between the two states comes down to the fact that a greater share of Arizona residents are exposed to scorching summer temperatures — and therefore more air conditioning usage, especially in population centers like Phoenix. (Average summer highs in Phoenix are about 20 degrees Fahrenheit higher than they are in Albuquerque, New Mexico’s largest city.) As a result, Arizonans use an additional 400 kWh every month, which leads to higher energy costs.

Arizona residents could also see higher prices in the coming years as a result of rate cases that are being considered, which, if approved, will take effect in 2026. Both Arizona Public Service and Tucson Electric Power are asking the state to approve a 14 percent increase in rates, which could translate to an increase of about $200 in average household energy bills per year. Both utilities have justified the increase by citing the need to modernize the grid as well as higher costs of constructing and maintaining infrastructure.

Key factor: Regulatory free-for-all

Texas is a land of contrasts. Though it’s an oil-and-gas stronghold, the Lone Star State generates a significant share of its electricity from wind and solar. And unlike most states, it operates its own power grid and runs a deregulated electricity market in which electricity prices can swing sharply from hour to hour.

In Texas, local utilities compete to buy power from generators — natural gas plants, wind farms, and solar arrays among them — in a wholesale market, and then sell that energy to customers. The system gives consumers a lot of choice in picking utility providers, but it also allows utilities to pass on wild swings in the price of power generation. If the cost of natural gas skyrockets during a particularly cold winter when solar is less available, for instance, wholesale electricity prices jump with it. This can lead to eye-popping energy bills, like those seen during 2021’s Winter Storm Uri. The setup ultimately leaves consumers exposed to price shocks, especially when extreme weather hits.

Perhaps as a result, rising electricity costs in Texas are driven by the cost of delivering power — and in particular by swings in natural gas prices, since gas-fired power plants are the state’s primary providers when weather conditions don’t enable wind and solar. While average retail electricity prices fell by a little more than 5 percent between 2019 and 2024, Texans still pay some of the highest energy bills in the country, reflecting surging demand driven by population growth and industrial expansions as well as sharp price spikes during the state’s scorching summers and winter months.

As the state’s population grows, new data centers get built, and more renewable power is brought online, utilities are also having to invest heavily to expand the grid and harden it against extreme weather like Uri, during which at least 246 people died, mostly due to hypothermia. One analysis found that transmission costs grew from $1.5 billion in 2010 to over $5 billion in 2024 and could surpass $12 billion per year by 2033.

Anita Hofschneider contributed reporting to this piece.

Five years ago, Winter Storm Uri brought the Texas power grid to its knees. Temperatures plunged across the state for nearly a week, power plants froze, natural gas supply lines failed, and the grid operator came within minutes of a total system collapse. More than 4 million Texans lost electricity, many for days. Over 200 people died. It was the worst infrastructure failure in modern Texas history.

In the years since, Texas has quietly built one of the largest renewable energy and battery storage fleets in the world. According to capacity data from the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, the state has added roughly 31 gigawatts of solar capacity and 17 GW of battery energy storage — enough to power millions of homes. Over the same period, the legislature mandated weatherization of power plants and natural gas infrastructure, ERCOT improved its operational procedures, and new market mechanisms were introduced to better coordinate solar and storage.

The results speak for themselves. Since Uri, the Texas grid has faced three major winter storms that each set new all-time winter peak demand records. In every case, the grid held. No rolling blackouts. No load shedding. No emergency curtailments. Demand kept climbing, and the grid kept delivering.

This track record matters because a prominent Texas think tank, the Texas Public Policy Foundation, has published a widely circulated analysis arguing that ERCOT’s reliance on solar and battery storage is making the grid less reliable in winter. The analysis is authored by Brent Bennett and uses real ERCOT data. But as this article will show, Bennett’s own numbers contradict his conclusions — and the actual performance of the grid over the past five years contradicts them even more decisively.

The following chart I worked up offers a quick summary: Texas’ reliability has increased dramatically in recent years in direct proportion to the renewables and battery storage it has added.

The above data tells the story. At the time of Uri, ERCOT had roughly 5 GW of solar and less than 1 GW of battery storage. When Winter Storm Elliott arrived in December 2022, it had 14 GW of solar and 2 GW of storage. By Winter Storm Heather, in January 2024: 22 GW and 4 GW. By Winter Storm Kingston, in February 2025: 30 GW and 9 GW. And now, as we pass the fifth anniversary of Uri: approximately 35 GW of solar and 15 GW of battery storage.

During each of these storms, peak winter demand set a new record — climbing from 74,525 MW during Elliott to 78,349 MW during Heather to 80,525 MW during Kingston. Just three weeks ago, the grid sailed through another major winter storm with over 11,000 MW of operating reserves and ERCOT said it did “not anticipate any reliability issues on the statewide electric grid.”

In none of these events did ERCOT order load shedding. This is the track record that Bennett’s analysis asks you to ignore.

Now let’s turn to Bennett’s projected numbers for 2030. His Figure 1 posits that ERCOT could have 103,802 MW of firm output against a speculative peak demand of 110,000 MW — his estimate, not ERCOT’s. That’s a gap of roughly 6 GW. His projected battery fleet by 2030? Forty-three gigawatts.

Read that again: a 6-GW shortfall covered by 43 GW of batteries.

Bennett’s response to this rather obvious mismatch is to reframe the question entirely. Instead of asking whether batteries can cover peak demand windows — which is what they’re designed to do — he converts the entire battery fleet into a single energy metric: 77 GWh, which he says is “equivalent to running a single 1 GW thermal power plant for the duration of this three-day storm.” It’s a striking comparison. It’s also irrelevant to how batteries actually operate in ERCOT.

Nobody designs, operates, or dispatches battery storage as a 72-hour baseload resource. Batteries are designed to shave peaks, provide rapid frequency response, and bridge the morning and evening demand ramps when solar output is low. A 43-GW battery fleet can inject enormous amounts of power during exactly the narrow peak windows that Bennett’s own Figure 2 identifies as the problem periods. During Winter Storm Heather, ERCOT’s post-storm analysis confirmed that batteries were “partially supplementing the lack of solar generation available” during the coldest pre-sunrise hours — the exact scenario Bennett says they can’t handle.

Perhaps the most revealing aspect of Bennett’s analysis is what he doesn’t discuss: the massive existing fleet of gas, coal, and nuclear generation that forms ERCOT’s backbone. He projects 103,802 MW of firm winter output in 2030. That fleet — overwhelmingly fossil and nuclear — carries the grid through the vast majority of every storm hour in his model. The assumed thermal outage rate is only 12% — a figure drawn from ERCOT’s reliability assessments — meaning 88% of the thermal fleet performs through the modeled storm.

Bennett constructs a scenario in which batteries fail by defining success as continuous 72-hour discharge, while simultaneously taking for granted the thermal fleet of 80-plus GW that keeps the lights on during the bulk of his modeled event. The batteries aren’t replacing that fleet. They’re supplementing it during the peak demand windows that the thermal fleet alone can’t quite cover — which is precisely the role that ERCOT’s system planning envisions for them.

The contrast between Bennett’s theoretical model and actual ERCOT performance is stark. During Winter Storm Elliott, solar contributed roughly 8 GW at peak, and real-time prices dropped from over $3,000/MWh to under $100 within 90 minutes of sunrise. During Heather, large flexible loads curtailed voluntarily, demonstrating the demand-side response that Bennett barely acknowledges. ERCOT CEO Pablo Vegas has specifically identified the growth in battery capacity as “perhaps the most significant factor affecting grid stability,” while University of Texas energy professor Michael Webber credited “significant investments in more solar and more batteries and demand response” as key factors in the grid’s most recent winter storm performance.

None of these experts are claiming the grid faces zero risk. ERCOT’s probabilistic risk assessment, as reported in NERC’s winter reliability assessment, puts the chance of controlled load shed this winter at about 1.8% — low, but not zero. The question is whether Bennett’s framework for evaluating that risk is sound, and on that point, the data he himself relies on says no.

Bennett’s piece concludes that ERCOT needs “market design changes that redirect revenue away from wind and solar and toward resources that can work in all types of weather conditions.” That’s a policy preference dressed up as an engineering conclusion. His own data doesn’t support it.

What his data actually shows is that ERCOT has a manageable peak-demand gap that battery storage is well positioned to address, supplemented by a massive thermal fleet that provides the overwhelming majority of firm capacity during winter events. The December 2025 launch of ERCOT’s Real-Time Co-optimization Plus Batteries (RTC+B) market is specifically designed to optimize exactly this kind of coordination — dispatching storage where and when it creates the most grid value.

The real question isn’t whether batteries can run for 72 hours straight. No one is asking them to. The question is whether the combination of 100-plus GW of firm thermal capacity, a rapidly growing battery fleet, improving demand-response capabilities, and better weatherization standards can keep the lights on during winter storms. The last five years of actual performance — including three consecutive record-breaking winter peaks — provide a clear answer.

Bennett’s analysis works only if you accept his premise that battery storage should be evaluated as a baseload replacement rather than what it actually is: a fast-dispatching, peak-shaving complement to the thermal fleet, which helps dramatically in firming up renewables like wind and solar. Reject that premise, and his crisis narrative dissolves into the numbers he himself provides.

A massive new battery has entered service in southern Maine, providing a much-needed boost to the Northeast’s efforts to expand clean and affordable energy.

Developer Plus Power wrapped up its Cross Town Energy Storage project in late November, but publicly inaugurated it last week in a ceremony featuring Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat, who has championed clean energy for the state and is currently running for Senate. Now, the small town of Gorham, nine miles inland from Portland, hosts a battery plant capable of injecting 175 megawatts for up to two hours, a bigger capacity than any other battery in New England.

“During Winter Storm Fern, we were 100% available and ready to contribute capacity with no emissions,” said Polly Shaw, chief external relations officer at Plus Power. “With a response capability of 250 milliseconds, there’s no faster asset that New England can rely on to help when they need capacity or grid services.”

New England states have issued a raft of energy storage targets in recent years, meant to complement their bevy of commitments to grid decarbonization. By 2030, Massachusetts aims to have 5 gigawatts, Connecticut 1 gigawatt, and Maine 400 megawatts. So far, however, it’s been slow going, even as storage has taken off in states like California and Texas. New England has managed to build just two battery installations with more than 100 megawatts: Plus Power’s Cross Town and its 150-megawatt Cranberry Point Energy Storage project, which came online in Massachusetts in June.

Plus Power has distinguished itself by entering into markets before they become saturated. For these two projects, the company won seven-year contracts in a 2021 forward capacity auction for the Independent System Operator New England, which runs wholesale power markets for the region’s six states. ISO-NE subsequently switched its capacity auctions to one-year awards — a move that complicates storage development in the region, as short-term contracts make it harder to attract project financing.

As it stands, Plus Power can claim the federal investment tax credit for 30% of the cost of the storage plant. Then it can earn revenue from the capacity contract and by bidding ancillary services in the wholesale market. Batteries can also arbitrage energy by buying when it’s cheap (typically when there’s an influx of renewable production) and selling when it’s expensive (typically when there’s increased reliance on gas-burning peaker plants).

Plus Power hired 25 full-time employees during construction of Cross Town and will employ two permanent maintenance staff now that the largely automated facility is running. It will contribute $8 million in tax revenue to Gorham, Shaw said.

Cross Town has an advantageous location in southern Maine, near Portland, the state’s biggest city. That allows it to work around transmission constraints, charging up when onshore wind farms are producing farther north, and then making that power available when Portland or points south need it, Shaw noted.

This serves Maine’s target of having 90% renewable and 100% clean energy by 2040, among the more assertive clean-energy goals in the country. Batteries can help this goal by improving utilization of renewable electricity. Maine also passed its 2030 storage mandate in 2021; Gorham knocked out nearly half of that single-handedly.

The state is planning a competitive storage solicitation this year to keep moving toward the target.

“Maine is such a leader on renewable energy, climate policy, and battery storage policy that it sent a long-term signal to come and invest in Maine,” Shaw said.

The battery could also tie into evolving conversations around energy affordability, which has become a primary political concern around the country. Mainers pay among the highest rates in the country for electricity and home heating. State energy analysts recently published a report that pinpointed fossil gas prices as a key driver of higher energy prices, since gas-burning plants typically set the market price for power in the region. Batteries provide peak power on demand without burning gas — and a broader build-out of facilities like Cross Town could put downward pressure on those sky-high prices.

This story was originally published in the Daily Yonder. For more rural reporting and small-town stories, visit dailyyonder.com.

When Chad Raines took over his family’s Texas cotton farm in 2008, he thought the going would be easy. That’s because their first year was relatively profitable — but the success was short-lived.

“The next 11 years was just loss after loss after loss,” Raines said in a Daily Yonder interview. “We just kept digging our hole deeper.” Raines soon began to question whether he should continue running the farm or pivot to something else.

Then came a third option, one in the form of solar panels and sheep: a type of farming called agrivoltaics. Now, he raises 3,000 head of sheep on about 8,000 acres throughout West Texas, and all under solar panels.

Raines is contracted by the solar companies to graze his sheep under their panels, keeping the vegetation short and feeding his sheep at the same time. He is one of a growing number of farmers leasing out their own land to renewable energy companies or grazing livestock on land already in use for solar or wind.

Scientists say widespread renewable energy development — the vast majority of which will be located in rural America — plays a key part in decreasing the country’s carbon emissions, but pushback from the Trump administration has stalled progress on many solar and wind projects.

In August 2025, the U.S. Department of Agriculture ended funding to loan programs that supported solar projects on farmland. The agency pointed to rising farmland prices as the primary reason for shutting down these projects.

“Our prime farmland should not be wasted and replaced with green new deal subsidized solar panels,” Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins said in a press release. The USDA defines prime farmland as land with the “best combination of physical and chemical characteristics for producing food, feed, forage, fiber, and oilseed crops.” These characteristics include a region’s growing season, soil properties, and water supply.

“Subsidized solar farms have made it more difficult for farmers to access farmland by making it more expensive and less available,” Rollins said.

Whether this claim is true is up for debate. Land use experts say the real threat to farmland is urban sprawl into rural areas, not solar development.

“Thousands of acres [of farmland] are going to [urban development], and that’s completely taking it out of commission,” said Jeff Risley, executive director of a new organization called the Renewable Energy Farmers of America. The group helps farmers negotiate land leases with solar and wind companies.

Once an area is turned from farmland into parking lots or apartment buildings, the likelihood of it returning to agricultural land is extremely low. “Solar and wind, it’s a 30- to 40-year commitment, but it can also go back to agriculture land at the end of that time,” Risley said.

Over the next two years, solar is projected to be the fastest-growing power generator in the country, according to a recent report from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. An estimated 83% of solar projects are expected to be built on farmland, according to projections from the American Farmland Trust.

While the estimated amount of farmland to be converted to solar is just a small fraction of the total farmland available in the U.S., for some rural residents, the transition is an unwelcome wave on the horizon.

In upstate New York, Alex Fasulo has spent the last year organizing against a solar project in the town of Fort Edward that would have an estimated 530-acre footprint with solar arrays, access roads, power lines, and a substation. She’s garnered more than 650,000 followers on Instagram alone, posting videos opposing the project, which is being conducted by the Canadian energy company Boralex.

For Fasulo, the solar development threatens the rural way of life she was looking for when she first moved to the area in 2023.

“I knew I was going to be surrounded by houses, farmhouses, and farms,” Fasulo said. “But [had I known] a commercial industrial complex would be able to come into this rural zoning, I would’ve bought land next to a Walmart [instead]. I didn’t sign up for this.”

This sentiment is shared by many neighbors of utility-scale solar projects, especially in states like New York, where there are more small communities interspersed with farmland, making solar development a lot more noticeable than in a state like Texas, where hundreds of acres of contiguous land can be developed far from any town.

“When solar comes into a place like that, it can feel like, ‘Oh my gosh, it’s taking over all of our land,’” Risley said. He tries to encourage the communities he works with to see solar projects as an opportunity rather than a threat to rural lifestyles. Risley recommends the use of a community benefit agreement, which is a contract between the solar developer and the town that can guarantee the building of a new grocery store or community center.

“On top of taxes that they might earn locally, you can also think about: What does our community need, and could this development help us achieve it?” Risley said.

Solar development on farmland could also help mitigate rural America’s carbon footprint. A 2025 report by the philanthropy organization Rural Climate Partnership found that 38% of the country’s total carbon emissions come from rural America, despite being home to less than 20% of the total population.

That’s because carbon-intensive industries are located in rural places — like agriculture, which accounts for 10.5% of total U.S. emissions. One way to shrink this footprint is through the widescale deployment of renewable energy projects, which the report said could create more rural jobs, provide tax revenue to local communities, and diversify farmers’ incomes.

“If you are used to looking at farmland that’s been growing corn or soybeans, I will not deny that replacing those crops with solar panels is a significant aesthetic change,” said Scott Laeser, senior working lands adviser for the Rural Climate Partnership.

“It’s a concern that we see raised, but I think that also assumes that our farmland has always been used the way that it’s used today, even though we used to have much more pasture and crop diversity in our agricultural landscape.”

To Laeser, introducing solar panels into the mix is just the latest in an ever-changing farm landscape.

“I think that as we build more solar projects and as developers incorporate design efforts … like trees and bushes along the edges of the projects to reduce the abrupt visual change, and people design projects based on topography as well, it can help minimize some of those concerns,” Laeser said.

But progress could be slow for at least the next three years because of the Trump administration’s attempts to limit solar development on farmland. This includes halting funding to the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP), which provides grants to farmers and rural small-business owners to install solar panels and make energy efficiency improvements to their operations.

“It’s really unfortunate because many of those [REAP] projects are not large, and so they’re not being built on prime farmland generally,” said Alex Delworth, senior clean energy policy associate at the Center for Rural Affairs. “They’re taking up a pretty small project size.”

The current status of REAP funding is unclear. In the same August announcement about ending funding to renewable energy loan programs, the USDA said it would ensure that “American farmers, ranchers and producers utilizing wind and solar energy sources” could install units that are “right-sized for their facilities.” No explanation was provided for how the USDA decides what is “right-sized” or not, and as of Jan. 19, 2026, there’s been no announcement for a new REAP grant cycle.

Regardless of what happens at the federal level, solar development is still underway in many parts of the country. Texas, where Chad Raines grazes his sheep, is projected to overtake California in solar production by 2030, according to research from the Solar Energy Industries Association. Much of this development will happen on farmland if current trends continue — and it could be one of the only ways farmers can make a living.

“If you want farmers or landowners to stop taking farmland out of agriculture and putting it into renewable energy, then the first thing that needs to be fixed is the farming landscape,” he said. Competing with large agribusiness has become a nearly impossible venture for most small and midsize producers.

“It needs to be more profitable for farmers to be able to make it,” Raines said.

Since the late 1800s, the grid has used more or less the same devices to convert electricity to different voltages. They’re called transformers — and they’re in increasingly short supply as power demand surges nationwide.

A crop of startups wants to solve that problem and modernize transformer technology at the same time — and they’re raising financing to do it.

On Wednesday, solid-state transformer startup Heron Power closed a $140 million Series B round from investors including Andreessen Horowitz’s American Dynamism Fund and Breakthrough Energy Ventures.

The new financing will allow the Northern California–based startup to build a factory at a yet-to-be-disclosed U.S. location capable of churning out 40 gigawatts of its medium-voltage power-conversion gear annually. It plans to start full-scale production in the second half of 2027 and have hundreds of megawatts of equipment produced by the end of that year.

Heron Power has already lined up 50 gigawatts of orders with more than a dozen prospective customers that are “actively engaged in technical product collaborations,” according to CEO Drew Baglino, who founded the startup in 2025 after an 18-year career at Tesla.

The firm is looking to initially sell not to utilities but rather to operators of solar and battery farms and data center campuses, which need to convert electricity as well. So far, it has disclosed only two of its early customers: Intersect Power, a major clean-energy developer that Google is acquiring for $4.75 billion, and Crusoe, a data center developer building a 1.2-gigawatt campus in Abilene, Texas.

While Baglino declined to share details about other prospective customers, he did say that Heron Power has been bringing many of them into its lab to see the prototype equipment being put through its paces. “We’re also doing integrated full-system deployments later this year,” he said. “It helps immensely for folks to get a sense of what we’re talking about and see the power processing in front of them.”

Heron Power isn’t the only company building next-generation power-conversion equipment. DG Matrix is planning to deploy its solid-state transformer via strategic partnerships with PowerSecure, a major developer of microgrids and data-center power systems that’s owned by utility Southern Co., and with Exowatt, a startup providing solar and thermal energy storage systems to data centers.

On Wednesday, the Raleigh, North Carolina–based DG Matrix announced a $60 million investment led by Engine Ventures and including Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and electrical-equipment manufacturing giant ABB. The Series A funding will enable the company to scale up manufacturing and deepen “strategic partnerships with datacenter developers, hyperscalers, utilities, and industrial customers,” according to the company’s press release.

Another startup in the space, Resilient Power, was acquired last year by electrical equipment giant Eaton in a deal worth as much as $150 million.

Solid-state transformers digitally manipulate the flow of electricity, employing the same kind of power electronics that are used in solar and battery inverters and in electric vehicle drivetrains. “Solid state” refers to the semiconductors that make that digital power manipulation possible. “Transformers” is a nod to the 19th-century electromechanical devices that convert the voltage of alternating current via copper wires wound around iron cores.

Solid-state transformers are a timely replacement for those devices for a couple of reasons. They’re far more flexible than old-school electromagnetic devices, meaning engineers can do more things with one device. They’re also urgently needed because conventional power equipment — particularly transformers — has been unable to keep up with the demand created by the fast-growing electricity sector.

The technology itself is not brand new. High-frequency digital power-switching technologies are already used for specialized purposes such as massive high-voltage direct current (HVDC) converters. And inverters — another form of digital power-switching tech — are an integral part of EV chargers and solar and battery installations.

Over the past decade or more, various efforts to expand the role of solid-state power-conversion technologies to replace a wider array of systems have struggled to gain traction, given high costs and technical challenges. But Heron Power’s Baglino thinks that the time is right for this tech, as costs come down and major customers seek out effective alternatives to the backlogged and increasingly expensive conventional options.

As with many other digital technologies, “power semiconductors have had their own version of Moore’s law,” Baglino said. In the past five years or so, these improvements have made it “not only feasible but economically attractive to replace inverter skids — with an old-school transformer at solar and battery facilities — with a power electronics solution.”

Those “inverter skids” he mentioned are shipping-container-size combinations of electrical gear — step-down and step-up transformers, switching and protection gear, and inverters themselves — that convert direct current from solar panels and batteries to grid-ready alternating current. Similar combinations of gear are used to convert grid electricity to direct current needed to power heftier commercial and industrial sites — such as data centers.

Unlike traditional high-efficiency transformers, solid-state power-conversion devices don’t need specialized grain-oriented electrical steel, which is now in short supply. Instead, they use the same silicon carbide and gallium arsenide semiconductor supply chains feeding EV markets, Baglino said, “and the EV supply chain has expanded rapidly over the past decade or so.”

Solid-state transformers also weigh less and take up less space than the gear they replace, he said. They’re capable of a wider range of functions, including regulating power quality fluctuations, which can wreak havoc on data centers, and they can be used for multiple applications, unlike traditional equipment.

As for the cost, Baglino said prices for Heron Power’s electronics are competitive with those for traditional tech. “We’re not asking for any premium over the solutions they’re buying right now.”

Like DG Matrix and Resilient Power, Heron Power is targeting data centers, solar and battery farms, and dense EV charging sites for early adoption, since that’s a “fast-growing market with motivated customers,” Baglino said.

Heron Power’s Heron Link devices are designed to handle typical utility distribution substation voltages of 34.5 kilovolts and to deliver 600-volt direct current. That higher-than-typical voltage aligns with the latest data center power architectures being pursued by major AI players such as Nvidia.

“But we have every intention of bringing the benefits of solid-state transformers to the AC-to-AC world,” he said, referring to the need for transformers to step voltage up and down without converting it to direct current. “A single SST can decouple faults, it can do power factor control, it can do voltage regulation, frequency regulation, all this monitoring and control of the power flow that utilities don’t have with passive transformers.”

While these are all useful capabilities, utilities are not eager adopters of novel technologies. Over the previous decade, companies that have built power electronics for utility distribution grids have closed up shop or have been acquired and fallen from public view.

But the combination of technical improvements and growing grid pressures may make this decade different. “Once we prove the technology is performing well” for solar farms and data centers, Baglino said, “we can go back to utilities.”

Back in the summer of 2024, Minnesota utility Xcel Energy proposed a novel approach to building virtual power plants, the networks of rooftop solar systems, home batteries, and other energy equipment that can operate in tandem to reduce strain on the electric grid.

Instead of working with other companies to cobble together solar arrays and batteries at homes and businesses — the traditional model for VPPs — Xcel wanted to install, own, and control those devices itself, using its grid expertise to deliver a better bargain for its customers at large.

Now, a year and a half later, the plan is in — and clean energy advocates, solar industry groups, and state agencies say it doesn’t live up to Xcel’s promises.

In filings with the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission, these groups say Xcel’s Capacity*Connect (C*C) plan, unveiled in October, is likely to be slower, more costly, and less impactful in relieving grid stresses and energy costs than the customer-centered VPP programs already in place or being rolled out — including one by Xcel in Colorado.

As Minnesota’s Office of the Attorney General wrote in its initial comments, “Although Xcel suggests that C*C is uniquely innovative, it may simply be a uniquely expensive way to accomplish the same thing other states have accomplished for less ratepayer money.”

Xcel is asking for permission to spend at least $152 million to deploy 50 megawatts of batteries, and up to $430 million for 200 megawatts, through 2028. Those costs will be borne by its customers. And as capital expenditures, they will offer the utility a guaranteed profit on every dollar spent — a perk Xcel wouldn’t get if it relied on the traditional VPP model.

In its petition to regulators, Xcel says the plan is a first step in learning how to best integrate distributed energy resources across its grid, as called for by state utility policy for the past decade. It also argued that “non-utility-owned resources could deliver, at best, a portion of the anticipated system and customer benefits.”

Backers of this utility-led approach include Jigar Shah, a Biden administration Department of Energy official who has long championed the value of using batteries and other distributed energy resources — DERs in the jargon — as an alternative to big, costly, and hard-to-build power plants and transmission lines.

“For the first time in my professional career, we have a utility company formally agreeing with the fact that distributed power plants are essential to maintaining reliability and meeting load growth,” Shah wrote in a December LinkedIn post. “This is a huge win for our entire industry, and efforts by industry groups to torpedo this proposal can’t see the forest for the trees.”

But John Farrell, co-director of the nonprofit consumer advocacy group Institute for Local Self-Reliance and a longtime utility critic, argues that Xcel Energy is trying to monopolize the grid value of solar and battery systems, which customers are already willing to pay for to save money and provide backup power.

Utility ownership might be an acceptable alternative if it could be done faster and cheaper than the VPPs being put together by solar and battery installers like Sunrun, Tesla, and a host of other companies, Farrell said. But “if utilities are supposed to be so good at this, why is the cost-benefit analysis underwater?” he asked. “And why is it so slow?”

Logan O’Grady, executive director of the Minnesota Solar Energy Industries Association, doesn’t want to be too critical of Xcel’s plan. After all, his group and other solar advocates have spent years pushing utilities to rely more on rooftop solar, backup batteries, and other DERs. It hasn’t been easy. Utilities have long been leery of the reliability of these technologies, and instead prefer tried-and-true grid upgrades and utility-controlled equipment.

“This has been a tricky one, because for 10 years, people on our side have been saying to the commission and utilities, there’s value in the distribution system — you should invest there,” he said.

That argument is backed by an analysis from the DOE, promoted by Shah during his tenure, that found rooftop solar systems, backup batteries, electric vehicles, smart thermostats, and grid-responsive water heaters could provide 80 to 160 gigawatts of VPP capacity by 2030 in the U.S. That would be enough to meet 10% to 20% of the nation’s peak grid needs and save utility customers roughly $10 billion in annual grid costs.

“So when [Xcel’s] proposal first came out, in one sense it was like, ‘They’re finally listening to us,’” O’Grady said. “But in another sense it was, ‘They’re going too far by proposing only utility ownership.’”

That’s a significant departure from the status quo, the Minnesota Solar Energy Industries Association, Coalition for Community Solar Access, and Solar Energy Industries Association trade groups wrote in comments to the Minnesota PUC. “Traditional VPPs are technology-agnostic portfolios of customer-sited and third-party-owned resources,” they wrote. “Participation is open, competitive, and decentralized.”

By contrast, Xcel’s C*C plan would rely completely on utility-owned batteries of between 1 and 3 megawatts, the kind that usually come in shipping containers. Xcel plans to pay an undisclosed amount to businesses or nonprofits willing to host those batteries on their properties. But rather than connecting the equipment in those customers’ buildings, the utility would instead connect the batteries directly to its grid, preventing them from providing emergency backup power to participating customers.

To secure customers willing to host those batteries, Xcel Energy has proposed hiring Sparkfund, a company founded in 2013 that has promoted the “distributed capacity procurement” concept that forms the basis of the C*C plan. Xcel’s plan marks its first stab at implementing distributed capacity procurement.

But deploying utility-owned batteries via a single commercial partner is “unprecedented in VPP programs and raises significant competitive-market concerns,” the solar trade groups wrote.

Chris Villarreal, president of consultancy Plugged In Strategies and former director of policy at the Minnesota PUC, shares those concerns. In comments filed on behalf of the R Street Institute, a free market–oriented think tank where he serves as an associate fellow, Villarreal recommended that regulators reject the plan or, at a minimum, “ensure Xcel does not exercise monopoly power at the expense of other competitive and potentially lower-cost alternatives.”

“There are a couple of things that annoy me about this from a practical perspective,” Villarreal told Canary Media. “One is the exercise of monopoly power over competitors.” Xcel is proposing to give Sparkfund access to grid and customer data that “no competitor would be able to get” without signing nondisclosure agreements, he said. “Meanwhile, we have community solar gardens, solar developers, storage developers, that want to do the same thing.”

This lack of grid transparency is troubling, O’Grady said, given Xcel’s track record of making it difficult for customers and third-party developers to add batteries and community and rooftop solar to its grid. “Minnesota has a grid-congestion problem, and lack of utility investment to solve that problem,” he said.

At the very least, Xcel should subject its battery systems to the same process third-party developers and customers must go through to connect to the grid, O’Grady said. Under the C*C plan, “they circumvent that entire waitlist to interconnect — and that doesn’t seem fair.”

State regulators anticipated these concerns. The Minnesota PUC’s 2024 order allowing Xcel Energy to pursue the C*C plan required the utility to compare the costs and benefits with those of “alternative models” using customer and third-party-owned resources.

But Xcel Energy appears to have short-shrifted that requirement, said Erica McConnell, a staff attorney at the nonprofit Environmental Law & Policy Center. Instead of offering a cost comparison, Xcel asserted in its petition that “anything less than full operational control and visibility of these assets — which will operate functionally as part of our system — could present safety risks for our employees and the public and could create cybersecurity risks for our system.”

These statements appear to ignore the experience of other utilities managing VPP programs, McConnell said. In essence, she said, the utility dismissed the prospect of alternative approaches by saying, “‘It’s dangerous if we let other parties do it.’ That’s disappointing to us. We need alternative pathways.”

Xcel Energy disputes that it ignored regulators’ instructions. The utility lacks “quantitative information” on those alternatives, and “would need to speculate on these costs and benefits, which would inevitably lead to unresolvable disputes,” it wrote in reply comments.

Xcel also highlighted that it’s offering customers and third-party developers other pathways to add solar and batteries to its grid, including its long-running community solar program and incentives for backup batteries. Nearly all of the more than 1.3 gigawatts of distributed solar and storage on Xcel’s system in Minnesota is owned by third parties, it noted.

But the C*C program is focused on solving a much broader range of challenges on its grid, which requires greater precision than Xcel can achieve from customer-owned batteries, the utility said. It argues that it needs such rigorous control over the systems to cut costs and improve overall grid reliability for customers at large, in what it called a “marked shift in distributed energy policy.”

Critics have their doubts, however, about whether the benefits of Xcel’s plan will outweigh the costs.

The Minnesota Office of Attorney General wrote in its comments that it supports efforts to meet the state’s carbon-cutting goals while keeping rising energy and grid costs in check. But it also asked regulators to put a “hard cap” on Xcel’s spending, noting that it “stands to be a quite expensive program.”

Xcel’s C*C budget calls for spending up to $430 million for deploying 200 megawatts of batteries, it wrote, which equates to $2,150 per kilowatt of battery installed — well above typical costs for grid batteries.

It’s also more expensive than what Xcel Energy intends to spend on a gas-fired “peaker” power plant it’s planning to build in Lyon County, Minnesota, the office noted. That’s despite data from DOE’s VPP report indicating that typical VPP capacity can be more than 40% cheaper than that of conventional peaker plants, which run only at times of extremely high demand.

And Xcel’s proposed budget is well above what the Public Service Co. of Colorado, Xcel Energy’s utility in that state, intends to spend on its proposed Aggregator Virtual Power Plant pilot program. That program will pay third-party aggregators that equip customers with resources — including batteries, smart thermostats, smart water heaters, smart heat pumps, and EV chargers — that can inject electricity onto the grid or reduce power use. It is targeting 125 megawatts of capacity for a five-year budget of $78.5 million, or roughly $625 per kilowatt.

Xcel says these comparisons don’t tell the whole story. The Colorado program covers only five years of payments to aggregators, while the Minnesota program is modeled to cover the cost of assets for 20 years, Xcel spokesperson Theo Keith told Canary Media in an email. “When you model both programs over 20 years, their costs are similar.”

“Capacity*Connect will be more complex to operate and coordinate than the Colorado [program],” Keith added, because it’s designed to do more than simply reduce peak electricity demands across the entire grid.

Instead, C*C is meant to target particular points on the utility’s distribution grid that might otherwise need costly upgrades. This is the portion of the system that, unlike giant transmission lines that cover long distances, brings power directly to homes and businesses. Costs related to the distribution grid are the single biggest driver of rising utility bills in the U.S.

“Through the deployment of distributed batteries, we (and thus our customers) will save more money by avoiding more expensive grid upgrades than the payments made to program participants,” Keith wrote.