Technological advances are expanding where geothermal electricity canbe produced - making it a cost-competitive, secure alternative to gas forindustry and other power-intensive users.

This analysis examines how advances in geothermal technology are changingthe prospects for geothermal electricity in Europe: its resource potential, costsand deployment trends. The report considers how policy conditions shape thepace of new projects and geothermal’s role in evolving electricity systems.

Modern geothermal is pushing the energy transition to new depths, opening up clean power resources that were long considered out of reach and too expensive. But today, geothermal electricity can be cheaper than gas. It’s also cleaner and reduces Europe’s reliance on fossil imports. The challenge for Europe is no longer whether the resource exists, but whether technological progress is matched by policies that enable scale and reduce early-stage risk.

Tatiana Mindekova

Policy Advisor, Ember

The EU’s Geothermal Action Plan must include clear commitments to liberate Europe’s power sector from costly fossil fuel dependency. The potential to replace 42% of coal and gas generation with geothermal is simply too significant to ignore. Ember’s report highlights the crucial role geothermal plays in delivering affordable energy, security, and competitiveness. With Energy Ministers and the European Parliament calling for concrete action, it is now up to the European Commission to remove the barriers to mass geothermal deployment.

Sanjeev Kumar

Policy Director, European Geothermal Energy Council

Europe has far more geothermal potential than is commonly accounted for. Next-generation geothermal strengthens Europe’s heat sector and extends its impact to clean, secure, and reliable electricity across much of the continent. Continued investment in innovation and supportive policy can turn this resource into a major pillar of EU’s clean firm power system.

Jenna Hill

Superhot Rock Geothermal Innovation Manager, Clean Air Task Force

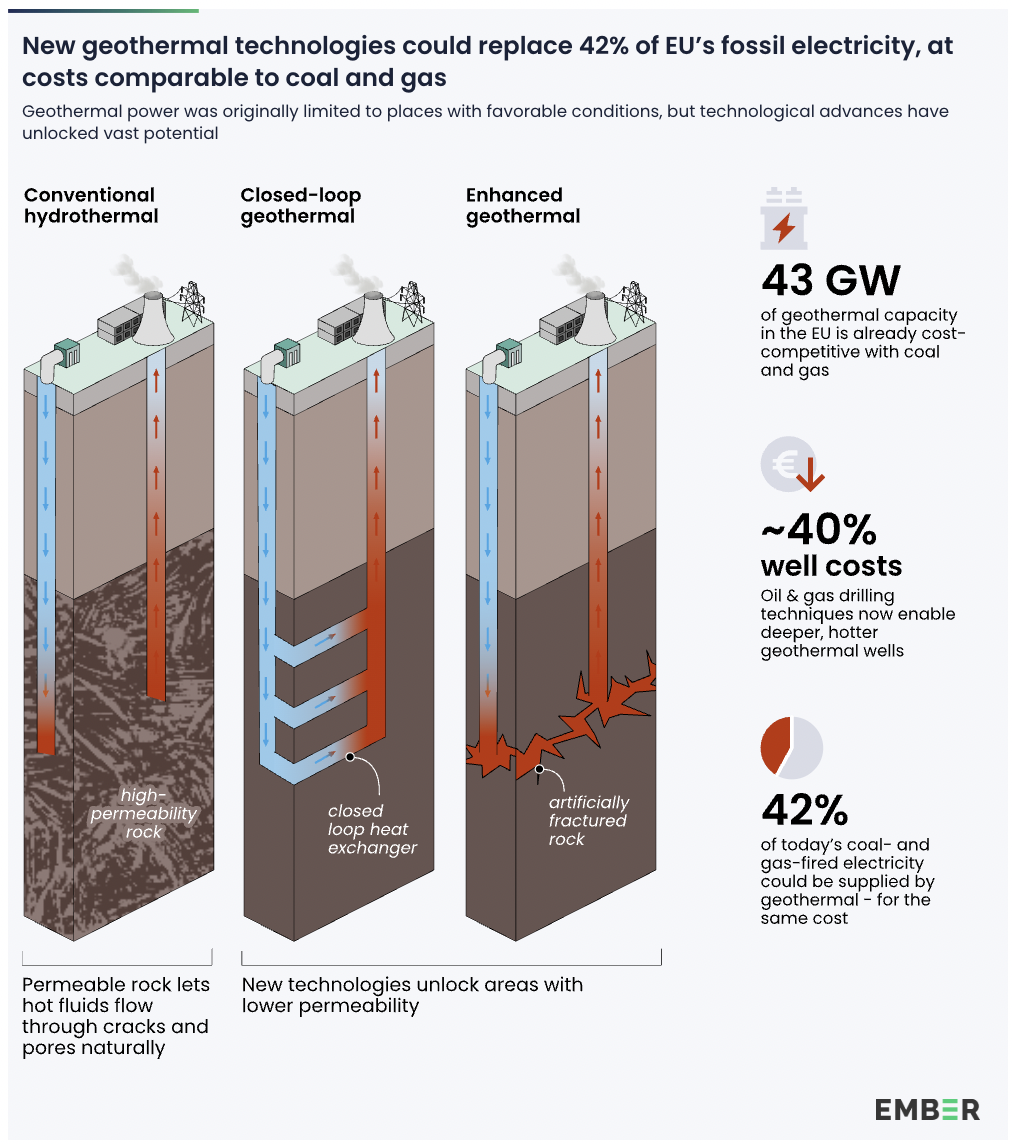

Technologies allow geothermal to deliver scalable and clean power across much of Europe. Not just in volcanic regions. Across the European Union, around 43 GW of enhanced geothermal capacity could be developed at costs below 100 €/MWh, placing geothermal firmly within reach as a competitive source of firm, low-carbon electricity. Yet much of this technological progress has gone largely unnoticed and geothermal is still widely viewed as unavailable across much of Europe.

Geothermal power generation was long considered viable only in volcanic regions such as Iceland or Indonesia. Conventional geothermal relied on underground rock formations that were both hot and naturally permeable, allowing water already present at depth to circulate and transport heat. These rare conditions confined large-scale deployment to a limited number of regions worldwide. As a result, geothermal energy remained a niche contributor to global electricity generation (99TWh or less than 0,5% in 2024) despite its dispatchable nature and low emissions profile.

During the last decade, progress in geothermal technologies – often referred to as ‘next generation geothermal’ – has removed the need for naturally occurring permeability, meaning the presence of open pores in rock that allow fluids to flow. New approaches can now create or enhance these flow pathways artificially. Combined with more cost-effective deep drilling and advances in power-conversion systems that enable electricity generation at lower temperatures, significantly expanding the range of geological settings suitable for geothermal power generation. As a result, geothermal deployment is expected to accelerate rapidly: by 2030, nearly 1.5 GW of new capacity is expected to come online each year globally, three times the level added in 2024. At the global level, geothermal could meet up to 15% of the growth in electricity demand by 2050.

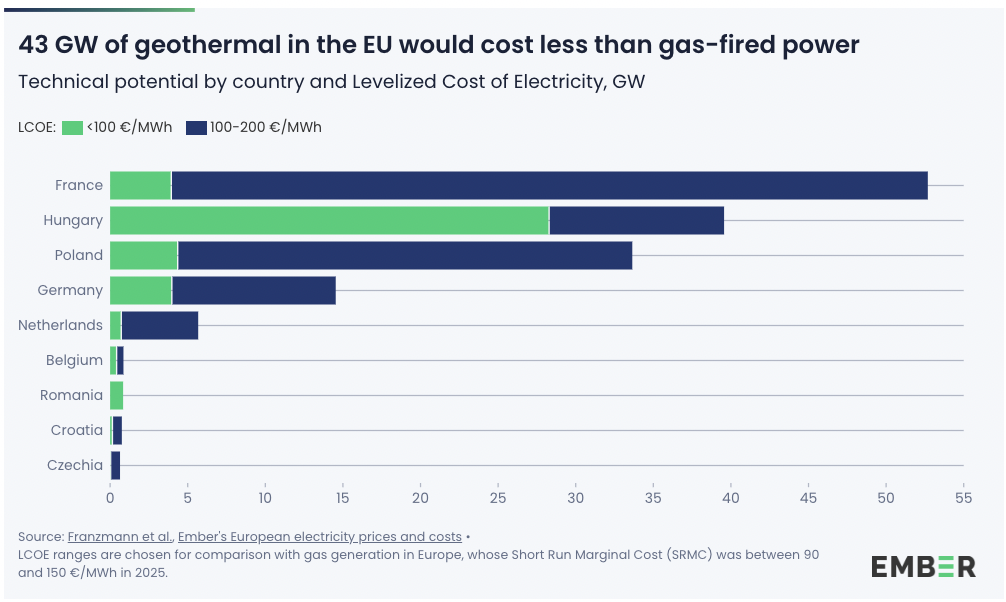

Recent advances in geothermal systems mean that geothermal electricity can now be produced at prices comparable to coal- and gas-fired generation, even outside traditionally high-temperature zones. Focusing on projects with estimated costs below 100 €/MWh – consistent with prices (short-run marginal costs) set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets – and accounting for reservoir behaviour, plant performance and drilling depth, the techno-economic potential for geothermal power in continental Europe reaches around 50 GW.

Under this threshold, Hungary accounts for the largest share, with around 28 GW, followed by Türkiye with almost 6 GW and Poland, Germany, and France with around 4 GW each.

For EU member states alone, this corresponds to around 43 GW of deployable geothermal capacity, capable of generating approximately 301.3 TWh of electricity per year given geothermal’s high capacity factor. This is equivalent to around 42% of all coal- and gas-fired electricity generation in the EU in 2025.

At these cost levels, geothermal power would be competitive with the prices set by coal- and gas-fired generation in European power markets, where short-run marginal cost has been oscillating between 90 and 150 €/MWh in 2025. Not only can geothermal power capacity be developed at low prices, but as a technology with no fuel costs, it brings the additional benefit of being insulated from fuel price volatility and exposure to rising carbon costs, strengthening its role as a stable source of firm, low-carbon electricity over time.

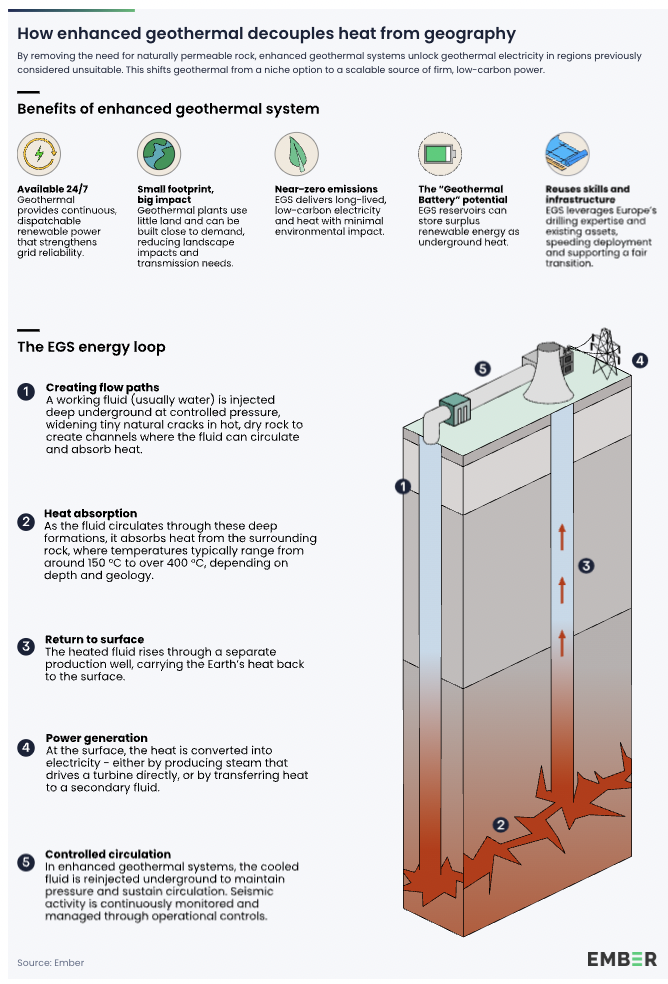

The potential of geothermal energy for electricity generation is expanded by changes in the design of geothermal projects. The term next-generation geothermal encompasses several design improvements to geothermal systems. These include accessing underground heat without relying on natural heat pathways, using artificial heat carriers, or creating closed-loop systems. A type of next generation technology most commonly deployed is Enhanced Geothermal System(s) (EGS). EGS can engineer reservoirs in deep, hot rock where natural water or permeability is low or absent, unlocking potential beyond traditional hotspots.

In EGS projects, wells are drilled into hot rock and permeability is created or enhanced to allow a working fluid to circulate and extract heat. The heated fluid is brought to the surface through these artificial cracks to generate electricity. Experience from recent projects shows that seismic risks resulting from such drilling can be managed through monitoring and operational controls.

Geothermal reservoirs can be operated flexibly to absorb surplus wind or solar electricity indirectly, primarily through increased pumping and injection, and later the release of stored thermal and pressure energy to generate additional power. By varying injection and production rates, operators can “charge” the reservoir and later “discharge” it to increase output during high-value periods. Simulations show that heat can be stored for several days with efficiencies comparable to lithium-ion batteries. Because this capability is built into the same infrastructure used for power generation, it adds flexibility at low additional cost.

In addition, geothermal operations can generate value beyond electricity through the recovery of critical minerals from produced brines. Lithium concentrations in geothermal brines typically range in levels that can be commercially viable using new direct lithium extraction techniques. These methods recover up to 95 % of the lithium contained in the brine, compared with roughly 60 % from hard-rock mining, while using far less water and generating almost no carbon emissions.

Geothermal electricity is already cost-competitive with fossil fuels in Europe. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) of geothermal power – the cost of producing one unit of electricity based on the construction and operating costs of a power plant over its lifetime – is already low, at around USD 60 /MWh, placing it below most fossil-fuel generation (~ USD 100 / MWh in Europe). This reflects geothermal’s high capacity factors and the fact that existing projects have largely been developed in favourable geological conditions using conventional designs, with average depth of well between 1 to 3km.

Drilling and reservoir development remain the dominant drivers of capital expenditure, making early-stage investment risk a central barrier for deeper and more complex projects. Over the past decade, however, drilling and reservoir-engineering techniques adapted from the oil and gas sector have reduced well costs by roughly 40%, enabling economically viable access to hotter and deeper resources. As these capabilities scale, they expand the share of geothermal resources that can be developed at competitive cost.

Geothermal electricity potential increases as drilling reaches deeper, higher-temperature resources, but the depth at which suitable temperatures occur varies significantly across countries. In the European Union, assessments limited to resources accessible at depths of up to 2,000 m — where sufficiently high temperatures are available only in a subset of locations — yield a relatively constrained level of technical potential (139GW). As access extends to deeper and hotter resources, geothermal conditions become more widely available across the EU. Extending the depth range to 5,000 m increases the estimated potential by more than 50 times, while access to resources down to 7,000 m results in an increase of roughly 180 times.

In the EU, projects that take advantage of the newly accessible resources are already under construction, reaching depths beyond 4000m. Moreover, there are existing projects that have already reached depths close to 5000m, demonstrating that utilising geothermal resources at these depths commercially is already achievable with today’s technology.

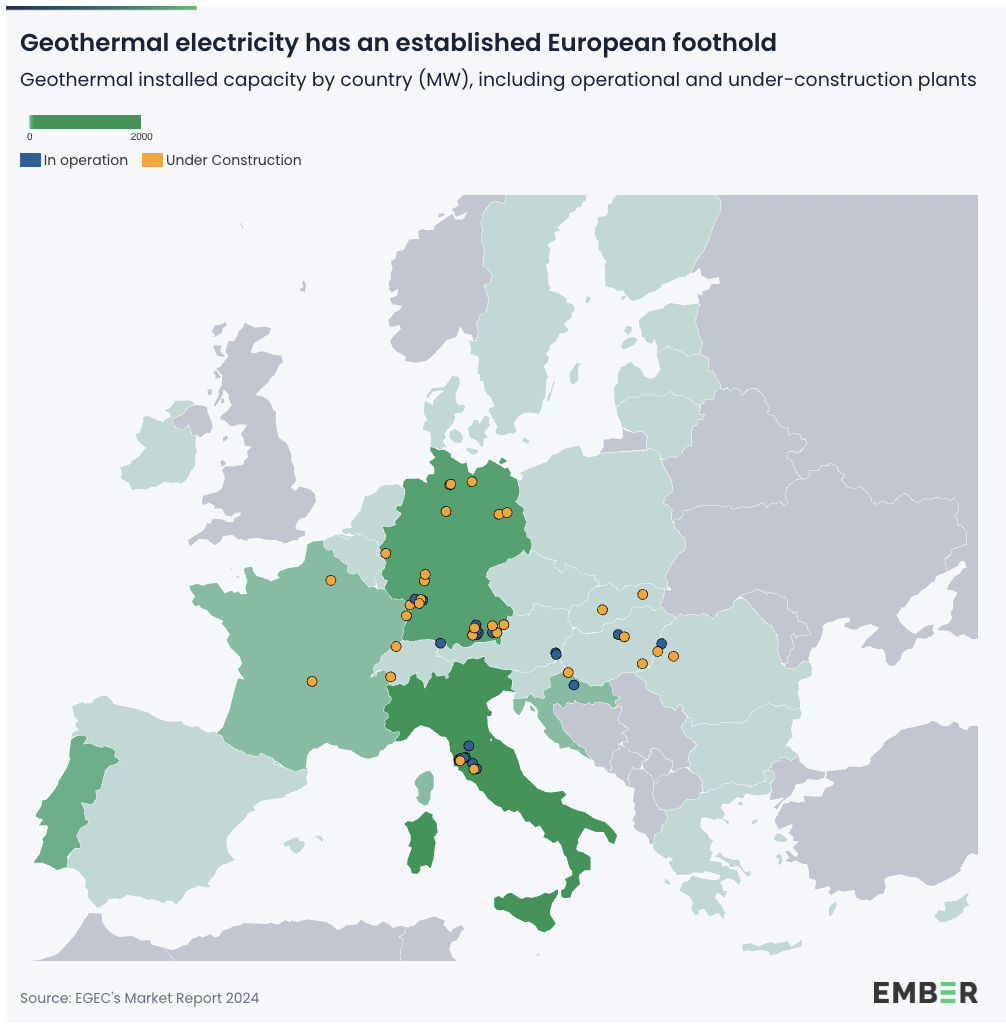

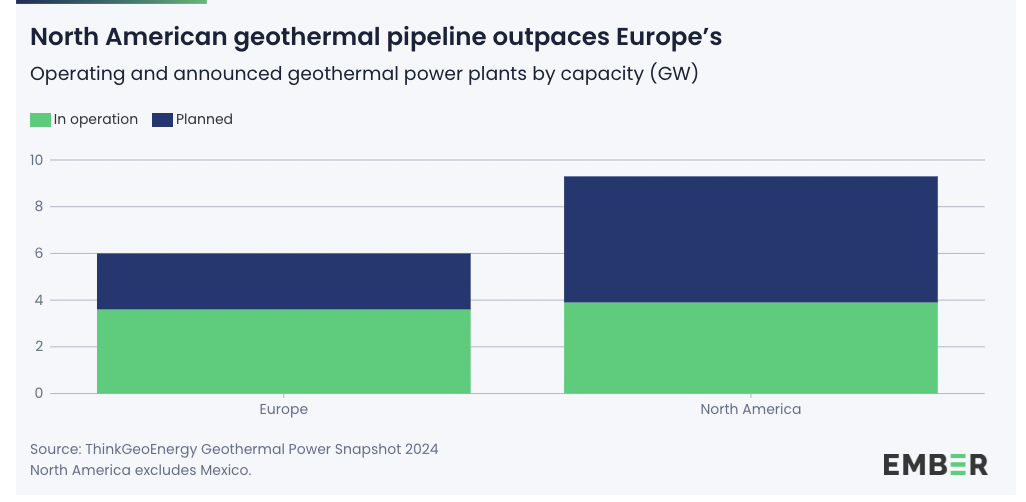

Europe played a central role in the development of geothermal energy. The world’s first geothermal electricity was produced in Italy, in 1904, and as of 2024, Europe had 147 geothermal power plants in operation. Of these, 21 have been producing electricity for more than 25 years, underscoring the long-term value of geothermal investments. In 2024, these plants produced around 20 TWh of electricity from just over 3.5 GW of installed capacity (roughly one-fifth of global geothermal capacity).

Geothermal generation in Europe remains highly concentrated. The majority of its output came from Türkiye, Italy and Iceland, which together accounted for nearly all geothermal generation in the region. Beyond these established markets, activity is spreading: several countries already produce geothermal electricity, including Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Austria and Portugal, while new capacity is under development in Belgium, Slovakia and Greece. Across Europe, around 50 geothermal power plants are currently moving through development, from early exploration to grid connection, with Germany leading in active projects.

Pilot EGS projects launched in France, Germany and Switzerland in the 2000s demonstrated that hot, impermeable rock could be converted into productive reservoirs. More than 100 EGS projects have now been carried out worldwide, with Europe accounting for the largest share (42), followed by the United States (33), Asia (15), and Oceania (12). More recently, EGS projects have moved from commercial demonstration to full scale development. Advanced geothermal systems are also progressing, with Europe’s first closed-loop project now operating as a grid-connected power plant in Germany.

Despite this progress, Europe is at risk of losing ground. Lengthy permitting processes, inconsistent national support and the absence of a coordinated EU strategy and accompanying policies have slowed commercial deployment. In contrast, projects in the United States and Canada are now scaling up many of the methods first tested in Europe, supported by targeted policy incentives and private investment. Delayed deployment also risks shifting learning effects, supply-chain development and cost reductions to other regions, increasing future costs for European projects even where resources are available. Without a stronger focus on market-scale financing, Europe may miss the economic and industrial benefits of technologies it helped pioneer.

Geothermal power plants could play a crucial role in meeting the fast-growing electricity demand of data centres, whose global consumption could more than double by the early 2030s. As data-centre capacity expands, geothermal offers a stable, always-available source of electricity that can be developed alongside these sites. Its continuous output helps balance the wider power system and reliably serves data centres energy-intensive operations over the long term.

Recent research by Project InnerSpace shows that if current clustering trends continue, geothermal could economically meet up to 64 percent of new data centre demand in the US by the early 2030s and even more when developments are located near optimal resources.

At the same time, AI is reshaping geothermal development. By analysing seismic and geological data, it helps identify promising sites, streamline drilling and improve performance – creating a feedback loop in which each technology accelerates the other.

Major technology companies are no longer experimenting with geothermal – they are deploying it. Announced in 2021 and now fully operational, Google’s partnership with Fevro marked the world’s first enhanced geothermal project built for a data centre. Others are following suit, with Meta signing a 150-megawatt deal with Sage Geosystems in the United States. In Europe, no similar cooperations were announced.

In the United States, geothermal power is now firmly within the clean-energy toolkit. Federal legislation such as the Inflation Reduction Act has expanded investment and production tax credits to include geothermal electricity, establishing clearer economic signals for developers. Meanwhile, geothermal enjoys bipartisan backing because it leverages drilling and subsurface expertise tied to familiar industries and offers around-the-clock output.

In Europe, several Member States, including Austria, Croatia, France, Hungary, Ireland, and Poland, have developed national geothermal road maps aimed at supporting subsurface investment, demonstration wells and domestic supply chains, in some cases backed by dedicated financing and targets.

Only more recently has momentum begun to build at the EU level. In 2024, both the EU Council and the Parliament voiced their support for accelerating geothermal and proposed a European Geothermal Alliance, to be set up by the Commission. As geothermal strongly aligns with the EU’s priorities on competitiveness, energy security and industrial decarbonisation, the forthcoming European Geothermal Action Plan is a much-needed and timely development.

However, translating strategic recognition into deployment will depend on how geothermal is integrated across broader EU policy instruments. As preparations for the next Multiannual Financial Framework advance, and initiatives such as the Industrial Decarbonisation Accelerator Act aim to strengthen permitting and demand signals for clean solutions, geothermal’s high upfront risk, long asset lifetimes and system value as a source of firm capacity make coordinated EU action particularly important. In practice, the effectiveness of European geothermal framework will hinge on progress in three areas at EU level:

Download the report here.

Hot stuff: geothermal energy in Europe [PDF]

Techno-economic geothermal capacity potentials for power in the EU are aggregated from data presented in the paper “Global geothermal electricity potentials: A technical, economic, and thermal renewability assessment” by Franzmann et al., whose cost curves are limited to the “Gringarten approach” for reservoir modelling (please refer to the original publication for further details).

Raw geothermal energy surface densities in Europe are computed starting from Global Volumetric Potential (GVP) data from the Geomap tool by Project Innerspace, in particular from the modules with 150 °C cutoff temperature (minimum for power applications) and depths of 2000 m, 5000 m and 7000 m.

GVP data points, reported on a geographical grid with 0.17×0.17 degrees latitude-longitude resolution, are then averaged over the surface of each analysed country to obtain national energy values, expressed in PJ/km2.

The conversion to useful electrical energy is then performed by multiplying each country’s total by exergy efficiency (~30%, based on a 150 °C temperature for hot rock and on a 25 °C temperature for ambient) and utilization (~20%, based on conservative ranges out of the GEOPHIRES v2.0 simulation tool) factors. Capacity equivalents are calculated assuming an 80% load factor and a 25-years lifetime for a modern geothermal power plant. Results from the steps in this paragraph were used to validate the methodology through benchmarking with aggregated values from “The Future of Geothermal Energy” report by IEA.

The extraction of the original GVP data by Project Innerspace was performed in November 2025. Features and availability of modules within the Geomap tool might have changed since then.

Estimates for electricity generation in the EU are based on an 80% load factor, consistent with the rest of the methodology and representative of modern geothermal power plants. While cumulative generation and capacity estimates for 2025 only would yield a load factor of around 65%, future technological (improvements in plant operations) and market (increases in electrification and grid availability) conditions can justify assumptions for utilization of geothermal power capacity at or above this level.

Throughout the report, “Europe” refers to the European Union plus Iceland, Norway, Switzerland, Türkiye, United Kingdom and Western Balkan countries, reflecting the geographical scope of geological resource assessments and existing geothermal deployment. Where analysis refers specifically to the European Union, this is stated explicitly.

The authors would like to thank several Ember colleagues for their valuable contributions and comments, including Elisabeth Cremona, Pawel Czyzak, Reynaldo Dizon, Burcu Unal Kurban, Eli Terry, and others.

We would also like to extend our gratitude to our partners Clean Air Task Force and European Geothermal Energy Council for providing external review as well as valuable data and insights.

The startup Fervo Energy has reportedly filed for an IPO to help fund its build-out of next-generation geothermal projects.

Nearly a year after first floating the idea, the Houston-based Fervo submitted a confidential S-1 filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, Axios Pro reported on Thursday. The startup has raised about $1.5 billion since 2017 as it works to build a 500-megawatt project in Utah — which would become the world’s largest “enhanced geothermal system” if completed as planned in 2028.

Fervo didn’t immediately return Canary Media’s requests for comment. When asked in December about a potential IPO, the company said by email, “We have a lot of capital needs going forward to fuel our planned growth and will be tapping a lot of different opportunities to make that happen.”

Fervo is at the fore of a fast-growing effort to unleash geothermal energy across the country. Geothermal represents only about 0.4% of total U.S. electricity generation, largely because existing technology is constrained by geography or challenging economics.

But new techniques developed by Fervo and its competitors are breathing fresh life into the century-old industry — and attracting significant funding as electricity demand soars, including from tech giants. Geothermal is also the rare form of clean energy to win acceptance from the Trump administration, which has spared the fledgling industry from the targeted policy attacks and sweeping funding cuts that it’s lobbed at wind and solar energy.

Thursday’s IPO news comes on the heels of two other major funding announcements this week from geothermal startups Zanskar and Sage Geosystems, both of which are pursuing unique approaches to harnessing Earth’s heat for providing clean, around-the-clock power.

On Wednesday, Zanskar said it raised $115 million in a Series C funding round led by Spring Lane Capital to develop its “gigawatt-scale pipeline” of projects. The Salt Lake City–based company uses AI and modern prospecting tools to identify naturally occurring reservoirs of hot water and steam that are hidden beneath the surface, without the visible signs — like vents and geysers — that typically help developers find hot spots.

Zanskar recently announced the discovery of one such geothermal system in western Nevada, which it says has the potential to produce more than 100 MW of electricity using traditional drilling technologies, marking a key proof point for the firm.

Meanwhile, Sage Geosystems said it closed over $97 million in Series B funding, in a round led by conventional geothermal giant Ormat Technologies and investment firm Carbon Direct Capital. The funding will support the build-out of Sage’s first commercial-scale project, to be located at one of Ormat’s existing power plants.

Sage’s approach to geothermal energy involves tapping into both heat and pressure from hot, dry rocks found deep underground. The company drills wells and fractures rocks to create artificial reservoirs that it pumps full of water. Sage then cycles the water in and out of the fracture and jettisons the liquid to the surface in order to drive turbines and produce electricity.

Fervo, for its part, also uses fracking tools to create artificial reservoirs for generating power. In 2023, the company hit a key milestone when it completed the world’s first commercial pilot system to use “enhanced” drilling methods. This 3.5-MW facility in Nevada was built with support from Google, which is also working with Fervo to develop 115 MW of geothermal energy to power the tech giant’s data centers in the state.

Now, along with the IPO filing, Fervo is gearing up to mark an even bigger achievement: completing the first 100 MW of its 500-MW Cape Station project in Utah and delivering power to the grid in October.

HAYDEN, Colo. — For decades, Dallas Robinson’s family excavation company developed coal mines and power plants in the rugged, fossil-fuel-rich region of northwest Colorado. It was a good business to be in, one that helped hamlets like Hayden grow from outposts to bustling mountain towns — and kept families like Robinson’s rooted in place for generations.

“This area, with the exception of agriculture, was built on oil and gas and coal,” said Robinson, a former town councilor for Hayden.

But that era is coming to a close. Across the United States, bad economics and even worse environmental impacts are driving coal companies out of business. The 441-megawatt coal-burning power plant just outside Hayden is no exception: It’s shutting down by the end of 2028. The Twentymile mine that feeds it is expected to follow.

Coal closures can gut communities like Hayden, a town of about 2,000 people. That story has been playing out for decades, particularly in Appalachia, where coal regions with depressed economies have seen populations decline as people strike out for better opportunities elsewhere. Robinson, a friendly, gregarious guy, fears the same could happen in Hayden.

“I grew up here, so I know everyone,” he said. “It’s hard to see people lose their jobs and have to move away. … These are families that sweat and bled and been through the good and the bad times in small towns like this.”

Struggling American coal towns need an economic rebirth as the fossil-fuel industry fades. Hayden has a vision that, at first, doesn’t sound all that unusual. The town is developing a 58-acre business and industrial park to attract a diverse array of new employers.

The innovative part: companies that move in will get cheap energy bills at a time of surging utility costs. The town is installing tech that’s still uncommon but gaining traction — a geothermal heating-and-cooling system, which will draw energy from 1,000 feet underground.

In short, Hayden is tapping abundant renewable energy to help invigorate its economy. That’s a playbook that could serve other communities looking to rise from the coal dust.

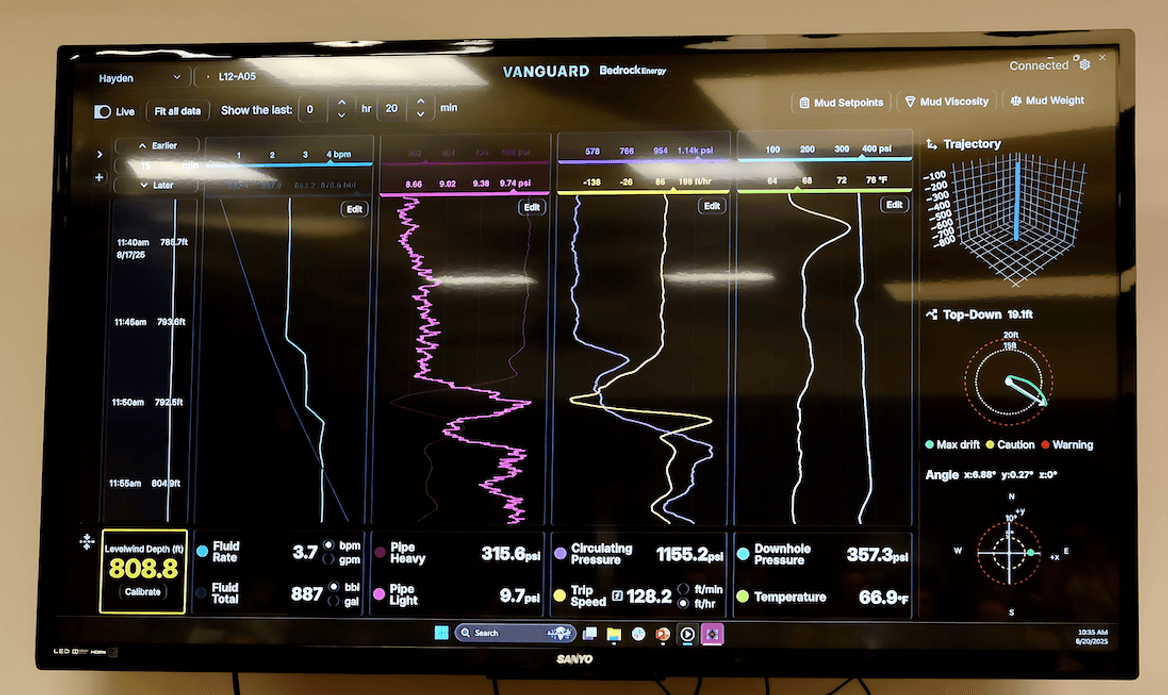

At an all-day event hosted by geothermal drilling startup Bedrock Energy this summer, I saw the ambitious project in progress. Under a blazing sun, a Bedrock drilling rig chewed methodically into the region’s ochre dirt. Once it finished this borehole — one of about 150 — it would feed in a massive spool of black pipe to transfer heat.

Bedrock will complete the project, providing 2 megawatts of thermal energy, in phases, with roughly half the district done in 2026 and the whole job finished by 2028. Along the way, constructed buildings will be able to connect with portions of the district as they’re ready.

“We see it as a long-term bet,” Mathew Mendisco, city manager of Hayden, later told me, describing the town as full of grit and good people. Geothermal energy “is literally so sustainable — like, you could generate those megawatts forever. You’re never going to have to be reliant on the delivery of coal or natural gas. … You drill it on-site, the heat comes out.”

Geothermal is also the rare renewable resource that the Trump administration has embraced. In July, Secretary of Energy Chris Wright, whose firm invested in geothermal developer Fervo Energy, helped convince Congress to spare key federal investment tax credits for the sector.

These incentives apply to both the deep projects for producing power as well as the more accessible, shallower installations for keeping buildings comfy. Unlike geothermal projects for power, ones for direct heating and cooling don’t depend on geography; any town can take advantage of the resource.

“We disagree on the urgency of addressing climate change, [but] this is something that Chris Wright and I agree on,” Colorado Senator John Hickenlooper (D), a trained geologist, told a packed conference-room crowd on the day of the event. “Geothermal energy has … unbelievable potential to, at scale, create clean energy.”

The eventual closure of the Hayden Station coal plant, which has operated for more than half a century, has loomed over the town since Xcel Energy announced an early shutdown in 2021.

The power plant and the mine employ about 240 people. Property taxes from those businesses have historically provided more than half the funding for the town’s fire management and school districts — though that fraction is shrinking thanks to recent efforts to diversify Hayden’s economy, Mendisco said.

Taking into account the other businesses that serve the coal industry and its workers, according to Mendisco, the economic fallout from the closures is projected to be a whopping $319 million per year.

“Really, the highest-paying jobs, the most stable jobs, with the best benefits [and] the best retirement, are in coal and coal-fired power plants,” Robinson said.

But coal has been in decline for over 20 years, largely due to growing investment in cheap fossil gas and renewables. While the Trump administration tries to defibrillate the coal industry and force uneconomic coal plants to stay open past their planned closure dates, states including Colorado still plan to phase out fossil fuels in the coming years. Colorado’s remaining six coal plants are set to shutter by the end of the decade.

Hayden aims for its business park to help the town weather this transition. With 15 lots to be available for purchase, the development is designed to provide more than 70 jobs and help offset a portion of the tax losses from Hayden Station’s closure, according to Mendisco.

“We are not going to sit on our hands and wait for something to come save us,” Mayor Ryan Banks told me at the event.

Companies that move into the business park won’t have a gas bill. They’ll be insulated from fossil-fuel price spikes, like those that occurred in December 2022, when gas prices leapt in the West and customers’ bills skyrocketed by 75% on average from December 2021.

In the Hayden development, businesses will be charged for their energy use by the electric utility and by a geothermal municipal utility that Hayden is forming to oversee the thermal energy network. Rather than forcing customers to pay for the infrastructure upfront, the town will spread out those costs on energy bills over time — like investor-owned utilities do. Unlike a private utility, though, Hayden will take no profit. Mendisco said he expects the geothermal district to cut energy costs by roughly 40%, compared with other heating systems.

The setup will deliver such massive savings because geothermal appliances, which draw energy from the always-temperate Earth, are the most efficient space-conditioning tech you can get. They pump out the same amount of heat as a fossil-fuel-fired furnace while using just one-sixth to one-quarter of the energy.

Municipally owned geothermal districts are rare in the U.S., but the approach has legs. Pagosa Springs, Colorado, has run its geothermal network since the early 1980s, when it scrambled to combat fuel scarcity during the 1970s oil embargo. New Haven, Connecticut, recently broke ground on a geothermal project for its train station and a new public housing complex. And Ann Arbor, Michigan, has plans to build a geothermal district to help make one neighborhood carbon-neutral.

Hayden’s infrastructure investment is already attracting business owners. An industrial painting company has bought a plot, and so has a regional alcohol distributor, Mendisco said.

One couple is particularly excited to be a part of the town’s clean energy venture. Nate and Steph Yarbrough own DIY off-grid-electrical startup Explorist.Life; renewable power is in the company’s DNA. The Yarbroughs teach people how to put solar panels and batteries on camper vans, boats, and cabins to fuel their outdoor adventures, and Explorist.Life sells the necessary gear.

“When we bought that property, it was largely because of the whole geothermal concept,” Nate Yarbrough told me. “We thought it made a whole bunch of sense with what we do.”

Reducing reliance on hydrocarbons, he noted, is “a good thing for society overall.”

The geothermal network that could transform Hayden’s future is mostly invisible from aboveground. Besides the drilling rig and a trench, the most prominent features I spotted were flexible tubes jutting from the earth like bunny ears.

Those ends of buried U-shaped pipes will eventually connect to a main distribution loop for businesses to hook up to. Throughout the network, pipes will ferry a nontoxic mix of water and glycol — a heat-carrying fluid that electric heat pumps can tap to keep buildings toasty in the winter and chilled in the summer.

Despite their superior efficiency, these heat pumps are far less common than the kind that pull from the ambient air, largely due to project cost. Because you have to drill to install a ground-source heat pump, the systems are typically about twice as expensive as air-source heat pumps.

But the underground infrastructure lasts 50 years or more, and the systems pay for themselves in fuel-cost savings more quickly in places that endure frostier temperatures, including Rocky Mountain municipalities like Hayden. Those long-term cost benefits were too attractive to ignore, Mendisco said.

Hayden’s project “is 100% replicable today,” Mendisco told attendees at the event, which included leaders of other mountain towns. Geothermal tech is ready; the money is out there, he added: “You can do this.”

Colorado certainly believes that — and it’s giving first-mover communities a boost.

In October, the state energy office announced $7.3 million in merit-based tax-credit awards for four geothermal projects. Vail is getting nearly $1.8 million for a network, into which the ice arena can dump heat and the library can soak it up. Colorado Springs will use its $5 million award to keep a downtown high school comfortable year-round. Steamboat Springs and a Denver neighborhood will share the rest of the funding.

At least one other northwest Colorado coal community is also getting on board with geothermal. In the prior round of state awards, the energy office granted $58,000 to the town of Craig’s Memorial Regional Health to explore a project for its medical campus.

With dozens of communities warming to the notion, “it’s an exciting time for geothermal in Colorado,” said Bryce Carter, geothermal program manager at the state energy office.

So far, the state has pumped $30.5 million into geothermal developments — with over $27 million going toward heating-and-cooling projects specifically — through its grant and tax-credit programs. The larger tax-credit incentive still has about $13.8 million left in its coffers.

Hayden, for its part, is also taking advantage of the federal tax credits to save up to 50% on the cost of its geothermal district. That includes a 10% bonus credit that the community qualifies for because of its coal legacy. After also accounting for a bonanza of state incentives, the $14-million project will only be $2.2 million, Mendisco said.

Tech innovation could further improve geothermal’s prospects, even in areas with less generous inducements than Colorado’s. Bedrock Energy, for one, aims to drive down costs by using advanced sensing technology that allows it to see the subsurface and make computationally guided decisions while drilling.

“In Hayden, we have gone from about 25 hours for a 1,000-foot bore to about nine hours for a 1,000-foot bore — in just the last couple of months,” Joselyn Lai, Bedrock’s co-founder and CEO, told me at the event. Overall, the firm’s subsurface construction costs from the first quarter of 2025 to the second quarter fell by about 16%, she noted.

Hayden is likely just at the start of its geothermal journey. If all goes well with the business park, the town aims to retrofit its municipal buildings with these systems to comply with the state’s climate-pollution limits on big buildings, Mendisco said. Hayden’s community center could be the first to get a geothermal makeover starting in 2027, he added.

Robinson, despite coal’s salience in the region and his family’s legacy in its extraction, believes in Hayden’s vision: Geothermal could be a winner in a post-coal economy. In fact, he’s interested in investing in the geothermal industry and installing a system in a new house he’s building, he said.

“I’ve lived a lot of my life making a living by exploiting natural resources. I understand the value of that — as well as lessening our impact and being able to find new and better,” Robinson said. “This is the next step, right?”

ITHACA, N.Y. — A faded-red wellhead emerged in the middle of a pockmarked parking lot, its metal bolts and pipes illuminated only by the headlights of Wayne Bezner Kerr’s electric car. He stepped out of the vehicle into the dark, frigid evening to open the fence enclosing the equipment, which is just down the road from Cornell University’s snow-speckled campus in upstate New York.

We were there, shivering outside in mid-November, to talk about heat.

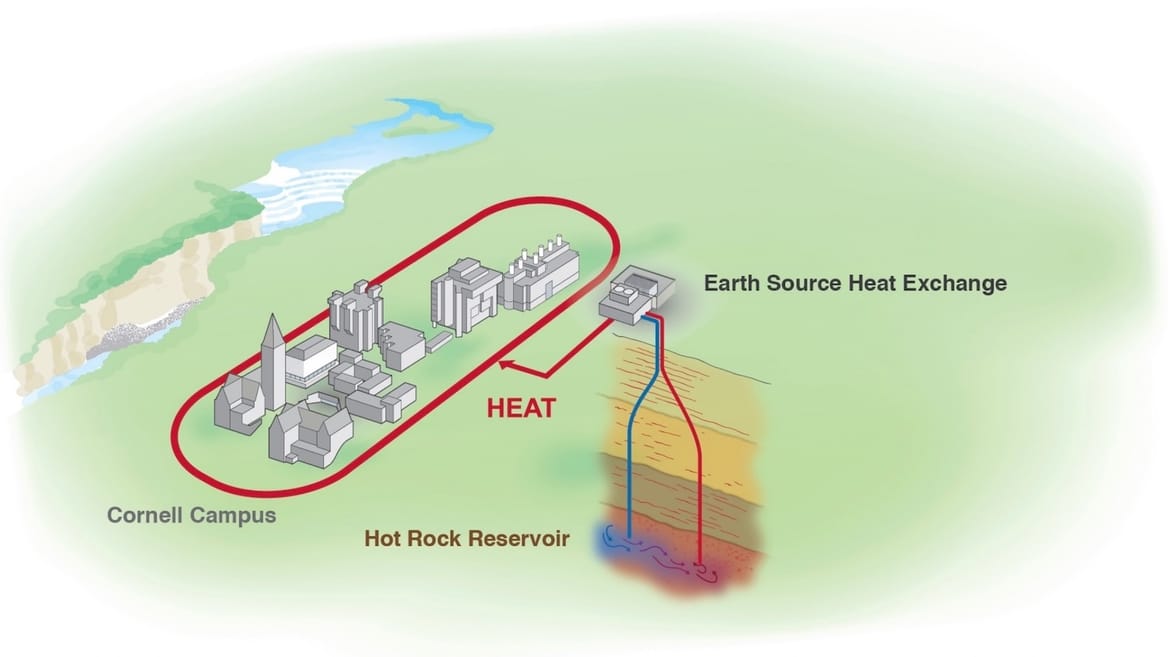

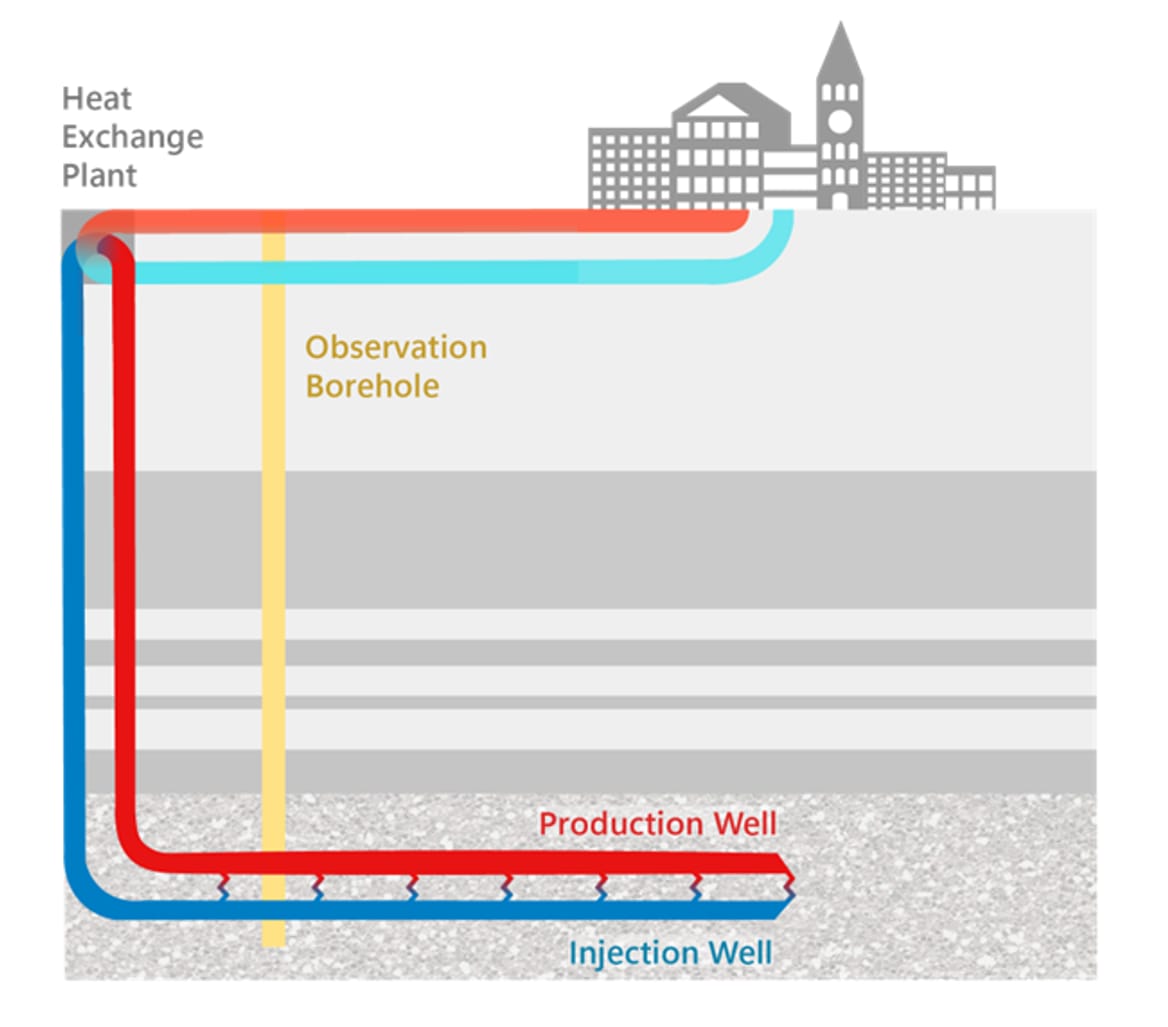

Bezner Kerr is the program manager of Cornell’s Earth Source Heat, an ambitious project to directly warm the sprawling campus with geothermal energy pulled from deep underground. The wellhead was the tip of the iceberg — the visible part of a nearly 10,000-foot-long borehole that slices vertically through layers of rock to reach sufficiently toasty temperatures. Cornell is using data from the site to develop a system that will replace the school’s fossil-gas-based heating network, potentially by 2035.

“We can’t decarbonize without solving the heat problem,” Bezner Kerr repeated like a refrain during my visit to Ithaca.

The Ivy League university is trying to accomplish something that’s never been done in an area with rocky geology like upstate New York’s. Most existing geothermal projects are built near the boundaries of major tectonic plates, where the Earth’s warmth wells up toward the surface. Iceland, for example, is filled with naturally heated reservoirs that circulate by pipe to keep virtually every home in the country cozy. And in Kenya and New Zealand, geothermal aquifers supply the heat used in industrial processes, including for pasteurizing milk and making toilet paper.

Bezner Kerr and I, however, stood atop a multilayered cake of mudstone, limestone, sandstone, and other rocks — seemingly everything but water. To access the heat radiating beneath our feet, his team will need to create artificial reservoirs more than 2 miles into the earth.

America’s geothermal industry has made significant strides in recent years to generate clean energy in less obvious locations, and it’s done so by adapting tools and techniques from oil and gas drilling. One leading startup, Fervo Energy, is developing “enhanced geothermal systems” in Utah and Nevada to produce clean electricity around the clock. The approach involves fracking impermeable rocks, then pumping them full of water so that the rocks heat the liquid, which eventually produces steam to drive electric turbines.

Earth Source Heat plans to use similar methods to drill a handful of super-deep wells and create fractures near or within the crystalline basement rock, where temperatures are consistently around 180 degrees Fahrenheit, no matter the weather above. The project is also unique in that, among next-generation systems, it’s focused only on heating buildings — not supplying electricity — for the nearly 30,000 students and faculty. That’s because heat represents the biggest source of Cornell’s energy use, and its largest obstacle to reducing planet-warming emissions.

On the chilliest days, the campus can use up to 104 megawatts of thermal energy, which is more than triple its peak use of electrical energy during the year.

Such a ratio poses a big conundrum for not only large institutions like Cornell but also any cold-climate cities that burn fossil fuels to keep warm, as well as manufacturing plants that require lots of steam and hot water for steps as varied as fermenting beer, making oat milk, and sterilizing equipment.

Right now, one of the most immediate ways to cut emissions from thermal energy use is to replace gas-fired boilers and the like with heat pumps and other electrified technologies. But that can substantially increase a city’s or factory’s electricity use. In an ideal world, all the new power demand would be satisfied by renewable energy projects and served by a modern and efficient grid, helping limit the costs and logistical headaches of ditching fossil fuels.

In reality, though, the U.S. electricity system is straining to keep up with the emergence of data centers, new factories, and electrified buildings and vehicles. Utilities are pushing plans to build new gas-fired power plants and proposing higher electricity rates to cover the costs. New York, for its part, is failing to meet its own goals for installing gigawatts of new renewables and energy storage projects by 2030, in part because of barriers to permitting projects in the state. New York’s independent grid operator recently warned of “profound reliability challenges” in coming years as rapidly growing demand threatens to outpace supply.

Geothermal heating could provide a way to curb thermal-energy emissions without burdening the electric system even more, said Drew Nelson, vice president of programs, policy, and strategy with Project InnerSpace, a nonprofit that advocates for geothermal energy use.

“Electrification is great, but that’s a whole lot of new electrons that need to be brought onto the grid, and a whole lot of new transmission and distribution upgrades that need to be made,” Nelson said by phone. “For applications like industrial heat, or building heating and cooling, geothermal almost becomes a ‘Swiss Army knife,’ in that it can help reduce demand.” Using geothermal energy directly is also far more efficient than converting it to electricity, since a lot of energy gets lost in the process of generating electrons.

Still, deep, direct-use geothermal systems like the one Cornell is developing are relatively novel, and many manufacturers and city planners are either unfamiliar with the solution or unwilling to be early adopters.

Sarah Carson, the director of Cornell’s Campus Sustainability Office, explained that Earth Source Heat is intended to reduce technology risks and costs for other major heat users that might benefit from geothermal, including the region’s dairy producers and breweries. We spoke inside her office, which is attached to the 30-megawatt gas-fired cogeneration plant that currently provides both electricity and heating for the campus.

“We’re working really hard to build a ‘living lab’ approach into the ethos of how we approach things,” she said. “Can we not only take care of our own [carbon] footprint but also help develop and demonstrate solutions that could scale out?”

Earlier on that overcast day, Bezner Kerr and I drove to the shores of Cayuga Lake.

Winds whipped up the grayish-blue waters, which form one of the 11 long, skinny Finger Lakes that glaciers etched into the Earth millions of years ago. Cayuga Lake is, in a way, the inverse of a heated geothermal reservoir. Cornell uses the chilly lake to cool the water that circulates across campus, replacing the need for industrial chillers that use lots of refrigerants and electricity.

Inside the Lake Source Cooling facility, giant blue pipes intersect through pieces of equipment called heat exchangers. Since heat naturally flows from hotter objects to colder ones, the lake water acts like a magnet, pulling heat out of the campus-water loop. The lake-water loop then moves the heat down to the cold bottom of Cayuga, and the cycle repeats. Bezner Kerr said Earth Source Heat will do the same but in reverse, flowing hot water up to the surface and returning the cooled-off water underground, where the earth can continuously reheat it.

Initially, he said, the new geothermal system will connect to an existing underground hot-water loop that heats East Campus, including two energy-intensive research buildings. This first stage is expected to cost over $100 million and could be completed in the next few years. Depending on how Earth Source Heat performs, the university might expand the system to warm around 150 large buildings on the main campus.

The university’s approach is far more intensive than the geothermal systems that cities and high-rise buildings are increasingly deploying across the country. An underground thermal network in Framingham, Massachusetts, consists of 90 holes drilled about 650 feet deep that heat 36 homes and commercial buildings; it also uses electric heat pumps to boost the temperatures coming out of the ground. Cornell’s home city of Ithaca has proposed piloting its own thermal network to heat and cool buildings on a city block.

Jefferson Tester, a Cornell professor and the principal scientist for Earth Source Heat, said these shallower geothermal systems aren’t as practical for heating the 15-million-square-foot campus.

For one, the university would need to drill north of 10,000 smaller wells to adequately warm all its buildings, instead of the five very deep wells it has planned. And digging deeper into the ground will allow Cornell to use the heat straight away, without adding heat pumps.

Tester joined Cornell in 2009 to help launch Earth Source Heat, which is part of the university’s larger plan to achieve a carbon-neutral campus in Ithaca by 2035. For over a decade, faculty and engineers gathered data and developed models to get a better sense of the region’s geology, heat resources, and potential for drilling-related earthquakes, often in partnership with the U.S. Department of Energy.

But to fully grasp the subsurface’s conditions, they needed to drill. “And once you understand the geology well enough … you could go anywhere in this region” to harness geothermal energy, Tester said.

In 2022, the university drilled that first 10,000-foot-long hole, which is called the Cornell University Borehole Observatory, in the parking lot. “It was the same level of intensity as an oil-and-gas exploration rig,” Bezner Kerr recalled. “It was oil-and-gas workers drilling a well that produces knowledge instead of producing hydrocarbons.” Cornell received about $7 million from the Energy Department for the project, which cost around $14 million to deploy.

Now the team is ready to drill again, though the timing of the next phase is up in the air amid funding uncertainty.

Earth Source Heat wants to reopen the borehole, deepen it, and use fiber-optic cables and other tools to study how the rock responds to stress and high-pressure injections of water — data that will inform the design of the final system. In 2024, during the Biden administration, Cornell applied for over $10 million from the Energy Department for the project, with plans to line up drilling equipment this year. But the Trump administration hasn’t yet responded to the request.

If the team can finish the second phase of its borehole observatory, the next step will be to drill a demonstration well pair — two vertical spines with horizontal legs, and fractured rocks in between — to begin heating part of East Campus.

The drilling delays come as Cornell faces growing criticism from climate activists both on and off campus, who argue that the university isn’t reducing its emissions nearly fast enough to help limit global temperature rise. Cornell on Fire, a climate-justice group, has raised concerns that Cornell is using Earth Source Heat as a “delay tactic to avoid undertaking necessary actions now on other critical fronts.” The group says Cornell should immediately provide more adequate funding for the geothermal project and be more transparent about its timeline for implementing the system.

Meanwhile, Carson said her office is feeling pressure from climate advocates to start replacing the current gas-fueled heating network with electrified technologies like heat pumps and electric boilers. But she and her colleagues believe that swiftly boosting Cornell’s electricity demand would require increasing gas-fired power generation off campus, reducing the school’s CO2 footprint on paper without lowering emissions overall. Even so, Carson’s team is evaluating a range of potential solutions, including heat-storing batteries and shallower geothermal networks, in case Earth Source Heat doesn’t work as well as hoped.

These tensions highlight the tricky reality of developing big and novel clean-energy projects. A well-designed, smartly managed geothermal system could help decarbonize heat for buildings and factories over the course of many decades. But finding the right locations and best ways to install those networks takes careful planning, patience, and significant upfront investment. That can be tough to stomach, both for project investors antsy to see financial returns and for citizens eager to dump polluting fossil fuels today.

“We’ve got to be thinking about a long-term, multigenerational commitment” for tackling climate change, Tester said. “And that is really hard for people.”

To Bezner Kerr, it doesn’t seem like larger discussions on decarbonization fully acknowledge just how big of a challenge heat represents — and what it would mean to electrify all the country’s heating needs. We were speaking then in his office, where a grayish chunk of Potsdam sandstone retrieved from deep below sat in a white plastic bucket next to his desk.

“It’s like there’s this huge train coming down the tracks,” he said. “And nobody realizes we’re about to get flattened by this thing if we do it wrong.”

A correction was made on Dec. 10, 2025: This story originally misstated Cornell on Fire’s position on the Earth Source Heat project; this piece has been updated to more accurately reflect the group’s stance.

The startup Fervo Energy just raised another $462 million to build America’s next generation of geothermal power plants.

On Wednesday, the Houston-based company said it closed a Series E funding round led by a new investor, B Capital, a global venture capital firm started by Facebook cofounder Eduardo Saverin. With the latest announcement, Fervo says it’s raised about $1.5 billion overall since 2017 as it develops what could become the world’s largest “enhanced geothermal system” in Utah.

“Fervo is setting the pace for the next era of clean, affordable, and reliable power in the U.S.,” Jeff Johnson, general partner at B Capital, said in a news release.

The Series E funding comes as Fervo reportedly prepares to become a publicly traded company, which would let it raise even more capital for its ambitious projects. When asked about a potential IPO, Fervo said only that the company is “focused on executing our development plan” in an email to Canary Media. “We have a lot of capital needs going forward to fuel our planned growth and will be tapping a lot of different opportunities to make that happen.”

Fervo is part of a burgeoning movement in the U.S. and globally to unleash geothermal energy in many more places.

The carbon-free energy from deep underground is available around the clock, but it represents only about 0.4% of total U.S. electricity generation — largely because the existing technology is constrained by geography. Today’s geothermal plants rely on naturally occurring reservoirs of hot water and steam to spin their turbines and generate power, which are available in a limited number of places.

Fervo’s approach involves creating its own reservoirs by fracturing hot rocks and pumping them full of water. The company uses the same horizontal drilling techniques and fiber-optic sensing tools as the oil and gas industry in an effort to reach deeper wells and hotter sources than is possible with conventional geothermal technology.

Its flagship development, Cape Station, is well underway in Beaver County, Utah. The project’s initial 100-megawatt installation is on track to start delivering power to the grid in October 2026, which will make it the first commercial-scale enhanced geothermal project to hit such a milestone worldwide, according to Fervo. An additional 400 MW is slated to come online in 2028.

“It’s very exciting to see at this point in time, because of the tangible progress that has been made,” Sarah Jewett, Fervo’s senior vice president of strategy, told Canary Media. “It’s really looking like a power project out there” in Utah, she added, noting that an electrical substation and three power facilities now sit alongside the drilling equipment and well pads. About 350 people currently work at the site.

Fervo has already completed a pilot project in Humboldt County, Nevada. The 3.5-MW facility went online in November 2023 and supplies power directly to the Las Vegas-based utility NV Energy. Google, which backed the project, also joined the Series E as one of Fervo’s new investors.

The financing announced this week will enable the startup to continue building Cape Station and to start development on other project sites where Fervo is conducting rock and soil analyses, Jewett said. One of the new projects will be in Nevada, where Fervo is working with NV Energy and Google to develop 115 MW of geothermal energy that will power the tech giant’s data centers. But the startup isn’t ready to disclose more details on the other locations.

Jewett said the fact that Fervo’s Series E was oversubscribed — meaning the firm raised more funding than it initially sought — is a reflection of the robust U.S. market for clean energy that’s available 24/7, not only for powering data centers but also for new domestic factories and electrified vehicles and buildings.

“There is just massive demand for the type of electricity that we’re providing,” she said.

Hot rocks might be the next big thing in energy.

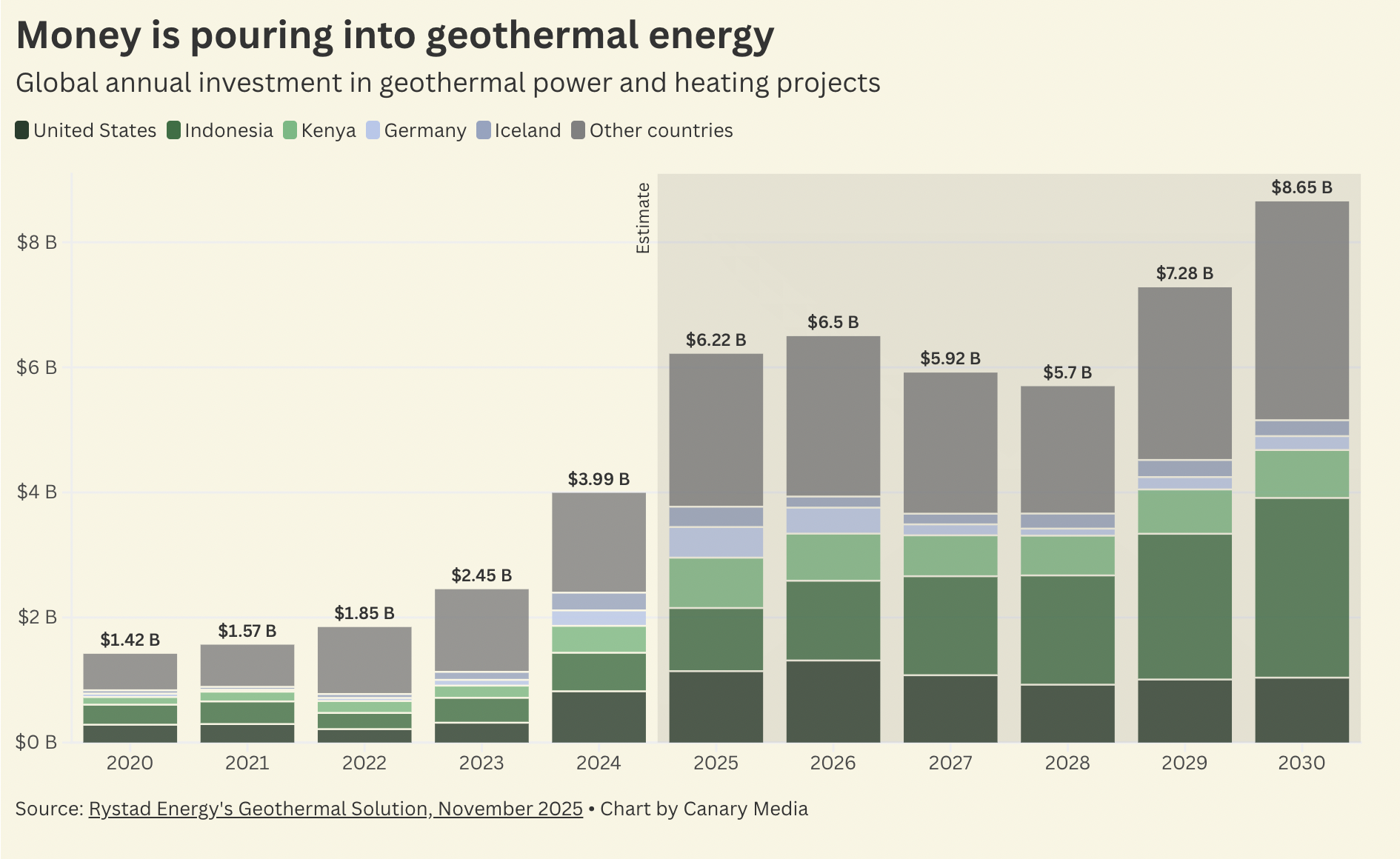

Global investment in geothermal energy is growing quickly — and it’s expected to keep climbing in the years to come, per new data from research firm Rystad Energy.

At the start of the 2020s, less than $2 billion flowed each year toward projects that harness the Earth’s natural underground heat to either produce electricity or directly warm buildings. By 2030, that figure could hit nearly $9 billion, Rystad predicts.

Geothermal systems have been around for decades in places where the Earth’s warmth sits close to the planet’s surface — think regions with lots of hot springs, for example. But decarbonization goals and rising power demand are fueling renewed enthusiasm for the always-available clean energy source, and emerging technologies mean companies can tap into it in areas with more challenging terrain.

Geothermal heating is most popular in Europe, where there’s growing interest in using the energy source for thermal networks that can warm up multiple buildings. Iceland, which has long leveraged its volcanic geology to keep homes toasty, is the famous example here.

When it comes to electricity, geothermal makes up less than 1% of the world’s supply. The U.S. is the global leader in terms of geothermal power capacity, with much of it located in California’s steamy Geysers region. It’s no surprise, then, that America is among the countries investing the most in the energy source, topping the chart this year and last.

Rystad doesn’t expect the U.S. to be No. 1 for much longer, predicting that volcano-laden Indonesia will steal the top spot for investment starting in 2027. Even so, geothermal could have a bright future in the U.S. It’s something of a unicorn: a clean energy source that has broad support among both Democrats and Republicans.

Geothermal energy is undergoing a renaissance, thanks in large part to a crop of buzzy startups that aim to adapt fracking technology to generate power from hot rocks virtually anywhere.

Meanwhile, the conventional wisdom on conventional geothermal — the incumbent technology that has existed for more than a century to tap into the energy of volcanically heated underground reservoirs — is that all the good resources have already been mapped and tapped out.

Zanskar is setting itself apart from the roughly one dozen geothermal startups currently gathering steam by making a contrarian bet on conventional resources. Instead of gambling on new drilling technologies, the Salt Lake City–based company uses modern prospecting methods and artificial intelligence to help identify more conventional resources that can be tapped and turned into power plants using time-tested technology.

On Thursday, Zanskar unveiled its biggest proof point yet.

The company announced the discovery of Big Blind, a naturally occurring geothermal system in western Nevada with the potential to produce more than 100 megawatts of electricity. It’s the first “blind” geothermal system — meaning that the underground reservoir has no visible signs, such as vents or geysers, and no data history from past exploration — identified for commercial use in more than 30 years.

In total, the United States currently has an installed capacity of roughly 4 gigawatts of conventional geothermal, most of which is in California. That makes the U.S. the world’s No. 1 user of geothermal power, even though the energy source accounts for less than half a percentage point of the country’s total electricity output.

The project is set to go into development, with a target of coming online in three to five years. Once complete, it will be the nation’s first new conventional geothermal plant on a previously undeveloped site in nearly a decade, though it may come online later than some next-generation projects.

“We plan to build a power plant there, and that means interconnection, permitting, construction, and drilling out the rest of the well field and the power plant itself. But that’s all pretty standard, almost cookie-cutter,” said Carl Hoiland, Zanskar’s cofounder and chief executive. “We know how to build power plants as an industry. We’ve just not been able to find the resources in the past.”

Prospecting is where Zanskar stands out. While surveying, the company’s geologists found a “geothermal anomaly” indicating the site’s “exceptionally high heat flow,” according to a press release. The team then ran the prospecting data through the company’s AI software to predict viable locations to drill wells in order to test the temperature and permeability of the system.

Zanskar drilled two test wells this summer. Roughly 2,700 feet down, the drills hit a porous layer of the resource with temperatures of approximately 250 degrees Fahrenheit. The company said those “conditions exceed minimum thresholds for utility-scale geothermal power” and “contrast greatly” with other areas in the region, which would require digging as far down as 10,000 feet — potentially viable for the next-generation technologies Zanskar’s rivals are pitching.

The firm’s announcement comes as the U.S. clamors for more electricity, in large part because of shockingly high forecasts of power demand from data centers. Many of the tech companies developing data centers, like Google and Meta, are eager to pay big for “clean, firm” power — electricity that is carbon-free and available 24/7. Geothermal, whether advanced or conventional, is a tantalizing option for meeting those standards, and tech giants already anchor some next-generation projects.

Ultimately, Zanskar thinks it can convince data centers to colocate near where it finds resources.

If it’s able to find additional untapped resources that are suitable for conventional technology, Zanskar could deliver new geothermal power faster and cheaper than the flashier startups on the scene can. Those firms, including Fervo Energy and XGS Energy, are making significant progress in bringing down the cost of their drilling techniques, but they are still using new technologies that remain more expensive than the traditional approach, which has been refined over time.

“The core reason we started the company is we came to believe that the Department of Energy’s estimates of hydrothermal potential were just orders of magnitude too low and were all based on studies that are over 20 years old,” Hoiland said. “We think that there’s 10 times more out there than they thought, and that every one of those sites can be 10 times more productive in terms of the number of megawatts they can generate.”

Among the notable cheerleaders of this same theory? The chief executive of the leading next-generation geothermal company. Responding to a post on X from Zanskar cofounder and chief technology officer Joel Edwards describing how much more conventional geothermal remains untapped, Fervo CEO Tim Latimer wrote, “Joel makes a great point about geothermal that you see all the time in resource development: when technology improves, turns out there’s a lot more of something than we thought.”

This story was first published by Inside Climate News.

The U.S. Department of Energy has approved an $8.6 million grant that will allow the nation’s first utility-led geothermal heating and cooling network to double in size.

Gas and electric utility Eversource Energy completed the first phase of its geothermal network in Framingham, Massachusetts, in 2024. Eversource is a corecipient of the award along with the city of Framingham and HEET, a Boston-based nonprofit that focuses on geothermal energy and is the lead recipient of the funding.

Geothermal networks are widely considered among the most energy-efficient ways to heat and cool buildings. The federal money will allow Eversource to add approximately 140 new customers to the Framingham network and fund research to monitor the system’s performance.

The federal funding was first announced in December 2024 under the Biden administration. However, the contract between HEET and the Department of Energy was not finalized until Sept. 30 and was just announced Wednesday. The agreement, which allows construction to move forward, comes as the Trump administration is clawing back billions of dollars in clean energy funding, including hundreds of millions of dollars in Massachusetts.

“This award is an opportunity and a responsibility to clearly demonstrate and quantify the growth potential of geothermal network technology,” Zeyneb Magavi, HEET’s executive director, wrote in a statement.

The existing system provides heating and cooling to approximately 140 residential and commercial customers in the western suburb of Boston. The network taps low-temperature thermal energy from dozens of boreholes drilled several hundred feet below ground, where temperatures remain steady at 55 degrees Fahrenheit. A network of pipes circulates water through the boreholes to each building, enabling electric heat pumps to provide additional heating or cooling as needed.

“By harnessing the natural heat from the earth, we are taking a significant step toward increasing our energy independence and promoting abundant local energy sources,” Charlie Sisitsky, Framingham’s mayor, wrote.

Progress on the project is a further indicator that despite their opposition to wind and solar, the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress appear to back geothermal energy.

President Donald Trump issued an executive order on his first day in office declaring an energy emergency that expressed support for a limited mix of energy resources, including fossil fuels, nuclear power, biofuels, hydropower, and geothermal energy.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, passed by Republicans and signed by Trump in July, quickly phases out tax credits for wind, solar, and electric vehicles. However, the bill left geothermal heating and cooling tax credits approved under the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 largely intact.

A reorganization of the Department of Energy announced last month eliminated the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy but kept the office for geothermal energy as part of the newly created Hydrocarbons and Geothermal Energy Office.

“The fact that geothermal is on this administration’s agenda is pretty impactful,” said Nikki Bruno, vice president for thermal solutions and operational services at Eversource. “It means they believe in it. It’s a bipartisan technology.”

Plans for the expansion project call for roughly doubling Framingham’s geothermal network capacity at approximately half the cost of the initial buildout. Part of the estimated cost savings will come from using existing equipment rather than duplicating it.

“You’ve already got all the pumping and control infrastructure installed, so you don’t need to build a new pump house,” said Eric Bosworth, a geothermal expert who runs the consultancy Thermal Energy Insights. Bosworth oversaw the construction of the initial geothermal network in Framingham while working for Eversource.

The network’s efficiency is anticipated to increase as it grows, requiring fewer boreholes to expand. That improvement is due to the different heating and cooling needs of individual buildings, which increasingly balance each other out as the network expands, Magavi said.

The project still awaits approval from state regulators, with Eversource aiming to start construction by the end of 2026, Bruno said.

“What we’re witnessing is the birth of a new utility,” Magavi said. Geothermal networks “can help us address energy security, affordability and so many other challenges.”

New Haven, Connecticut, has broken ground on an ambitious geothermal energy network that will provide low-emission heating and cooling to the city’s bustling, historic Union Station and a new public housing complex across the street.

The project will play a crucial role in the city’s attempt to decarbonize all municipal buildings and transportation by the end of 2030. As one of Connecticut’s first geothermal energy networks, it will also serve as a case study of how well the technology can both lower energy costs and reduce greenhouse gas emissions as the state considers promoting wider adoption of these systems.

“At the end of the day, you’re going to have the most efficient heating and cooling system available for our historic train station as well as roughly 1,000 units of housing,” said Steven Winter, New Haven’s executive director of climate and sustainability. “Anything we can help do to improve health outcomes and reduce climate change–causing emissions is really valuable.”

In climate-conscious states across the country, thermal energy networks are emerging as a promising way to reduce reliance on fossil fuels for heating, lower utility bills, and create a pathway for the gas industry to transition its business model for a cleaner-energy future. These neighborhood-scale systems use ground-source heat pumps and a web of underground pipes to deliver heating and cooling to connected buildings.

The thermal energy for heating can come from a variety of sources, including geothermal systems, industrial waste heat, and surface water. Because no fossil fuels are directly burned to produce heat, the only emissions are those created generating the electricity to run the network. At the same time, the systems insulate customers from volatile and rising natural gas prices.

“There’s a lot of excitement around networked geothermal because it actually offers solutions to a lot of problems,” said Samantha Dynowski, state director of Sierra Club’s Connecticut chapter. “It can be a more equitable solution for a whole neighborhood, a whole community — not just a single home.”

The practice of deploying such systems as a neighborhood loop is relatively new, but the component parts are well established: Geothermal heat pumps have been around for more than 100 years, and the pipe networks are very similar to those used for natural gas delivery.

“The backbone technology is the same kind of pipe you use in the gas system,” said Jessica Silber-Byrne, thermal energy networks research and communications manager for the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition. “They’re not experimental. This isn’t an immature technology that still needs to be proved out.”

There are a handful of networked geothermal systems around the United States, owned by municipalities, private organizations, and universities. A couple of miles away from the Union Station project, at Yale University, development is underway on a geothermal loop serving several science buildings.

But the idea is catching on among gas utilities, too. The nation’s first utility-owned geothermal network came online in Framingham, Massachusetts, in June 2024, and just received an $8.6 million federal grant that will allow it to double in size. Across the country, 26 utility thermal energy network pilots are underway, and 13 states have passed some form of legislation exploring or supporting the approach, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition.

In Connecticut, a comprehensive energy bill that passed earlier this year established a grant and loan program to support the development of thermal energy networks. Advocates are now pushing Gov. Ned Lamont, a Democrat, to issue the bonds needed to fund the new initiative.

The New Haven network could provide a concrete example of the opportunities offered by such systems.

The plan began when the federal government was seeking applications for its Climate Pollution Reduction Grant program, an initiative created by President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. Union Station seemed like an excellent property to retrofit because of its age, its size, and its prominent role in the city: Nearly a million travelers pass through the station each year, making it one of Amtrak’s busiest stops and an excellent platform for demonstrating the potential of geothermal networks.

“We thought it would be a powerful message to send for this beautiful landmark building that’s also the gateway to the city,” Winter said.

In July 2024, the federal program awarded the proposal just under $9.5 million; though there were questions earlier in the year about whether the Trump administration would attempt to block the money, the grant program ultimately proceeded. Planners expect federal tax credits and state incentives to cover the remaining $7 million in the project budget.

The network will use as many as 200 geothermal boreholes. Fluid will circulate through pipes in each of these wells, picking up thermal energy stored within the earth; in hotter weather, when cooling is needed, the systems will transfer energy back into the ground.

The city began drilling the first test boreholes in November. The results were promising: One test hole was able to extend down 1,200 feet, significantly farther than the 850 feet projected, Winter said. If more boreholes can be drilled that deep, it could mean fewer holes are needed overall — and thus less materials — making the project more efficient, he said.

Construction of the network is still in the early stages. The test boreholes should be completed this month, and the design of the ground heat exchanger — the underground portion of the system in which the thermal energy is transferred — is about halfway done, Winter said. The city is also preparing to accept proposals for the retrofit of the heating and cooling systems in the station itself.

The goal is to have the system up and running in the latter half of 2028. The apartment units, which are still in the design phase, will be connected to the system as they are built.

Even as the initial plan comes together, New Haven is already considering the possibility of expanding the nascent network to include more buildings, such as other apartment units under development nearby, existing buildings in the neighborhood, and a police station around the corner, Winter said.

“Ideally, we end up with a municipally owned thermal utility that can help decarbonize this corner of the city and provide affordable, clean heating and cooling,” he said.

In the early 2000s, the owners of the Mammoth Pacific geothermal station proposed expanding the plant into an area just east of California’s Yosemite National Park. The project boasted on its website in 2004 that the potential new wells, which would be located in one of the state’s richest heat resources, had been “carefully chosen to reduce or avoid potential environmental impacts.”

By 2009, the company had produced a study on how the development could impact plant life. The power station had been running since the 1980s, so the decades of data on its safe operation seemed to bode well for a swift approval at a moment when, much like today, rising electricity demand and concern over climate change were converging to bolster development of carbon-free power. The prospects looked so good that, in 2010, geothermal giant Ormat Technologies bought the company that owned Mammoth. In 2013 — a decade after the expansion was first conceived — federal regulators gave the project the green light.

Yet that was just the start of Mammoth Pacific’s permitting saga.

An environmental group and local opponents quickly accused regulators of failing to properly consider how the geothermal project could release organic gases into the atmosphere and groundwater, and filed a lawsuit under the California Environmental Quality Act. The litigation took years to resolve. By the time Ormat finally completed the expansion in 2022, the so-called Casa Diablo IV project had been in the works for nearly two decades.

“People in the industry know it took 17 years to expand an existing facility,” said Joel Edwards, the cofounder and chief technology officer at the geothermal startup Zanskar. “And that’s the last facility that’s been built in California.”

Building a new geothermal plant from scratch on an undeveloped site, he said, would presumably “be an even bigger lift.”

A bill that California lawmakers passed almost unanimously last month promised to change that calculus for the geothermal industry. AB 527 would have provided geothermal developers with categorical exemptions to CEQA reviews, clearing the way for companies to carry out the most expensive part of the process — drilling wells to identify viable hot-rock resources — without the costly burden of lawsuits and ecological assessments the state’s landmark environmental law imposes. A companion bill, known as AB 531, gives geothermal energy projects the same special “environmental leadership” status as solar, wind, energy storage, and hydrogen facilities.

But, in a move that has mystified the industry, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) vetoed AB 527. In his letter explaining the rejection, Newsom said the legislation would have required state regulators to “substantially increase fees on geothermal operators to implement the new requirements imposed by the bill.”

Of more than half a dozen industry executives and analysts that Canary Media spoke to, however, none believed that argument.

“Something doesn’t add up,” said Samuel Roland, a research fellow at the Foundation for American Innovation who has tracked the bill. “It was a political play for him.” The foundation is a right-leaning think tank that advocates for speeding up energy deployments.

While Roland said it’s difficult to determine exactly which groups may have persuaded the governor to block the legislation, “the only people who were objecting were environmentalists,” a dynamic that echoes the fight against Mammoth Pacific’s expansion.

“It does seem like it was a giveaway to environmental groups,” Roland said.

Izzy Gardon, a spokesperson for Newsom, declined to comment. “The Governor’s veto message speaks for itself,” he wrote in an email to Canary Media.

California’s unique geology has made it the destination for the geothermal industry for decades. The Western Hemisphere’s first commercial geothermal power station opened in California in 1960. That plant — The Geysers geothermal complex, located in a valley of the Mayacamas Mountains north of the San Francisco Bay Area — remains the world’s largest electrical station powered by the planet’s heat.

The state has enormous untapped potential — and a growing need for electricity. California has shut down all but one of its nuclear power plants over the past few decades. In recent years, persistent drought has made the state’s hydroelectric stations less dependable. Solar generation has soared, and a growing fleet of batteries has helped steady the supply when sun-soaked days threaten to overwhelm the grid with electrons and dark nights send panels’ production plummeting. But the state remains reliant on natural gas and power imports from neighboring states to meet surging demand. To achieve its carbon-cutting goals and bring down electricity rates that are more than double that of nearby states, California needs to increase its supply of clean, firm generation.

Burning biomass, such as dry wood cleared from California’s forests to help prevent wildfires, could provide one option — but that still generates carbon dioxide, and the demand for wood might encourage logging of healthy trees. Despite the state’s reversal of its plan to shut down Diablo Canyon, its final atomic station, building new nuclear reactors is still banned in California. Hydropower is dogged by water scarcity. That makes geothermal a particularly attractive choice.

It’s not without some drawbacks. Conventional geothermal, which involves drilling down into underground reservoirs warmed by volcanic heat, is limited to easily accessible areas and comes with the challenge of maintaining the subterranean water source over time. Next-generation geothermal companies are rapidly advancing drilling techniques that the oil and gas industry perfected in recent years to go deeper and harvest heat from dry, hot rocks, vastly expanding the locations with potential to generate energy. In a seismically active state, that carries some risk since the version of next-generation geothermal that uses hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, technology to drill could trigger earthquakes.

But every energy source comes with challenges, and neighboring states such as Utah, Nevada, and New Mexico are aggressively pursuing next-generation geothermal projects.

In theory, the best place to develop those first-of-a-kind plants would be California, with its energy-affordability woes and status as a major global economy.

“Utah has low prices, and geothermal is still expensive,” said Thomas Hochman, director of infrastructure and energy policy at the Foundation for American Innovation. “If you want to bring geothermal down to cost parity with other technologies, you have to sell it to Californians. As a result, geothermal scaling runs through California.”

For the most part, however, developers are steering clear of the Golden State. Companies such as Fervo Energy, XGS Energy, and Sage Geosystems — three of the biggest next-generation startups — are based in Houston and are pursuing debut projects in Utah, New Mexico, and Texas itself. Zanskar, a developer using modern prospecting methods to tap conventional geothermal resources, is headquartered in Salt Lake City. States such as Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, and Oregon are “really exciting” as potential next areas for development, Edwards said.

“If California ever fixes CEQA,” he added, “it could be huge.”

The regulatory hurdles represent “the only real barrier” to geothermal taking off in the Golden State, said Wilson Ricks, a Princeton University researcher who focuses on geothermal.

“You can find projects pretty much all across the Western states but very few, if any, in California, despite it being the biggest potential market,” Ricks said.

“It’s stark. People are exploring projects in Texas, which has far, far worse-quality resources than the ones in California,” he added. “That’s because of the regulatory environment there. So the fact that regulatory barriers are going to remain in place doesn’t give me a lot of confidence that California’s going to be leaping ahead on geothermal anytime soon.”

In response to emailed questions, Fervo said it maintains leases near the Salton Sea region, an area with vast geothermal potential. But those parcels aren’t currently under development since the state’s permitting regime makes investing in drilling too risky.