After Susan Lindsay got rooftop solar panels installed on her home in Greensboro, North Carolina, she wanted the low-income households she visited as a parent educator to be able to do the same — but without the expense.

“I realized how hard that would be for any of these families I was working with, but also how quickly it reduced my energy burden,” she said. “I started looking around for people trying to get clean energy into the hands of people who don’t make as much money.”

Soon, Lindsay found a coalition of groups working to solarize their communities. The basic concept has been around for nearly two decades: Organizers vet installers, negotiate prices, and recruit as many residents as possible to go solar during a limited sign-up window. The more participants, the lower the cost, thanks to the power of bulk purchasing.

As part of Solarize the Triad — a campaign that covers the north-central region of North Carolina, anchored by the cities of Greensboro, Winston-Salem, and High Point — Lindsay raised money and in-kind donations to help low- and moderate-income families go solar. Plus, she said, “I introduced my neighbors to all the ways they could get solar panels,” and many did. “I feel like I multiplied my contribution.”

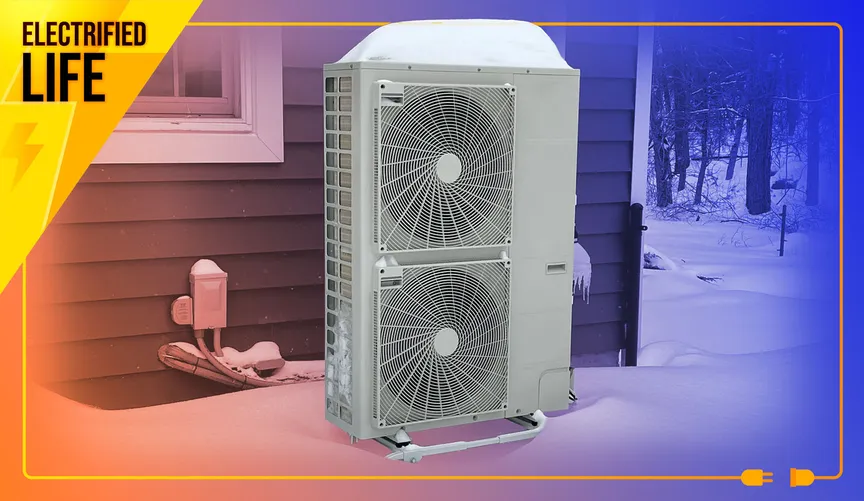

Indeed, in a campaign that ran from July 2024 to the following May, Solarize the Triad led to three houses of worship and over 70 households installing solar. Now, Lindsay is among those kicking off a similar effort called Electrify the Triad, which officially launched last Saturday. The latest initiative focuses on electrification: switching out gas heat, stoves, and hot water appliances for electric versions; installing EV chargers; and increasing efficiency — all steps to reduce fossil-fuel combustion, improve indoor quality, and lower household bills.

Lindsay plans to participate in the program, too — not just recruit for it. “I’m doing this because I really want to be more energy-efficient and to help other people be more energy-efficient,” she said. “It’s not enough for me just to make my house work. We need to do this collectively.”

When it comes to electrification, “information is power”

Backed by many of the same nonprofit partners that made Solarize the Triad a success, including the Piedmont Environmental Alliance and the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters Foundation, the electrification initiative includes contractors ready to install electric heat pumps, hook up induction stoves, upgrade electrical boxes, and make other energy-saving home improvements.

Undergirding Electrify the Triad is Bright Spaces, a Georgia-based firm that has supported over 20 Solarize campaigns around the country by bringing organizers, installers, and participants together through its online platform. Electrify the Triad is its third electrification effort; the others are in the Atlanta suburb of Decatur and Buncombe County, home to Asheville, where the company also has an office.

Of course, not all lessons from Solarize the Triad — a discrete project focused on one technology — will translate to the electrification campaign, which has no set end date. The key benefit of Electrify, said Ken Haldin, development partner for Bright Spaces, is that organizers identify contractors and help participants navigate how to cut costs and reduce their carbon footprint when they’re ready.

“With solar, you either have it or you don’t,” Haldin said. The options under the electrification umbrella, by contrast, are myriad, and a homeowner could swap out old, inefficient appliances with electric versions over time, rather than all at once. “It’s less binary than solar is. It’s much more a matter of choice and timing.”

The new campaign comes at a key moment for households looking to ditch their gas appliances. While the Trump White House and congressional Republicans have already eliminated some tax credits for home solar and efficiency and are attempting to dismantle others, the administration of North Carolina Gov. Josh Stein, a first-term Democrat, is pushing in the opposite direction.

Last year, North Carolina was the first in the country to launch a home energy rebate program created with funds from the Biden-era climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act. State officials announced last month that the cash-back program aimed at low- and middle-income households, which was rolled out in phases, is now available in all 100 counties. Each family can access up to $14,000 for electrification and up to $16,000 for home energy-efficiency upgrades.

Participation in Electrify the Triad isn’t limited by income, but the state rebates will help expand it to scores of households that otherwise might not be able to afford the up-front cost of high-efficiency appliances, added insulation, and other energy-saving measures, even though the outlays will pay for themselves over time in the form of lower utility bills.

“Information is power,” Haldin said. “If you can be guided on the proper way to move forward” on electrification, he said, “then you’re already on a money-saving track. And if someone can point you to an incentive that’s applicable, now you’ve redeemed a coupon you didn’t know you had.”

Building on the success of Solarize

Among the designers and planners of Electrify the Triad is Shaleen Miller, sustainability and intergovernmental relations director for Winston-Salem. While the city’s climate target of carbon neutrality by 2050 is limited to its own vehicles, buildings, and other operations, she said, “what’s good for the city residents is good for the city.”

Now that the program is officially launched, other members of the team are beginning outreach. That includes Dawn Lewis, a retiree who, with her husband, recently moved from Austin, Texas, to Winston-Salem to be closer to her adult children on the East Coast.

In Texas, Lewis, a member of the United Methodist Church, had embraced the “creation care” philosophy. “Creation is this incredible gift, and we’re asked to do a good job of taking care of it, and we’ve kind of done a horrible job,” she explained. “So, it’s important for us to go out there and try to resolve that.”

After starting a creation care group at her church in Austin, she formed a network of groups from other Methodist churches around the city. “I’m working to do that same thing here,” she said, starting with Ardmore United Methodist Church in Winston-Salem and expanding to other houses of worship throughout the Yadkin Valley.

Lewis, who also participated in Solarize the Triad, said many of the same organizing tactics will apply to Electrify: reaching out to neighborhoods, businesses, and communities of faith to have person-to-person and group conversations.

“The hope is to try to get as many people as possible aware, educated, and then engaged,” she said. “Solarize was successful. I think this will be, too.”

.svg)