U.S. carbon emissions increased in 2025, even as clean energy installations surged.

Economy-wide emissions rose by 2.4%, according to a new analysis of federal data by the research firm Rhodium Group. This ended a two-year streak of emissions reductions and clocks in as the third-largest emissions increase in the last decade. The country is still emitting 18% less than it did in 2005 (compare that to President Barack Obama’s goal of a 26% to 28% reduction by 2025), but the economy has resisted a smooth glide toward decarbonization.

“It’s not the most notable increase that we’ve seen, but in the context of this bumpy downward trend, it is an up year,” said Rhodium Group research analyst Michael Gaffney.

Some of that emissions increase came from factors that Gaffney referred to as statistical “noise,” namely a very cold winter that pushed up space-heating needs in buildings. That kind of variation is to be expected. But changes in the power sector could be more potent signals of things to come.

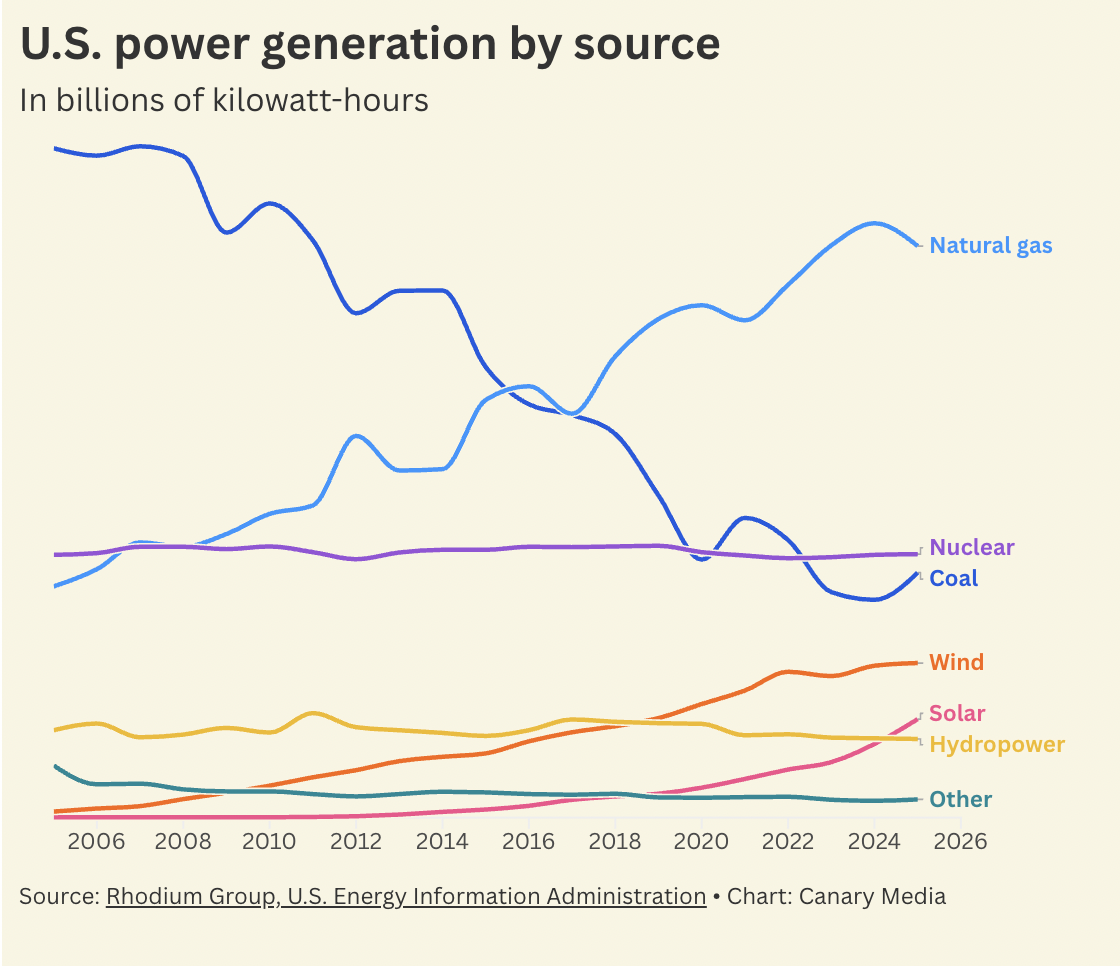

The power sector has generally led the U.S. economy in emissions reductions, largely because gas plants have outcompeted coal plants over the last two decades, and gas emits less carbon when burned than coal. But in 2025, coal proved that it’s not dead yet. Natural gas prices rose by 58% over 2024 levels, under pressure from space-heating demand and global exports via liquefied natural gas terminals. At the same time, demand for electricity soared: Generation increased by 2.4% from the year before, as data centers, crypto miners, and electric vehicles consumed more energy.

Taken altogether, the rise in demand at a time when gas was less economically competitive gave coal an opening in the markets, and its generation surged by 13% in 2025.

“This year is a bit of a warning sign on the power sector,” Gaffney said. “With growing demand, if we continue meeting it with the dirtiest of the fossil generators that currently exist, that’s going to increase emissions.”

AI data center demand shows every sign of increasing far beyond 2025 levels in the years ahead. That’s while export capacity for liquefied natural gas is on track to double by 2029, greatly expanding competition for U.S. gas supplies. The Trump administration has issued a flurry of “emergency” orders to block coal plant retirements, and many utilities are also choosing to push back planned coal plant closures as they respond to the sudden growth in power demand, Gaffney said.

Coal generation has plummeted by 64% from its peak in 2007, but it has rebounded for brief periods along that trajectory. 2025 offered a reminder that coal isn’t on a one-way street to obsolescence. Even without new coal plant construction, existing plants can ramp up operations when the opportunity arises, and could well continue to do so over the next few years.

The data from 2025 also challenges another truism in climate advocacy circles: that breakthroughs in climate technologies have decoupled economic growth from emissions growth. Last year, though, emissions increased faster than real GDP, which grew by a projected 1.9%, per Rhodium.

“Were this to persist, this would be a troubling sign for the broader transition, just because we’ve predicated this whole thing on ‘you can grow the economy without exploding emissions,’” said Ben King, Rhodium’s director of U.S. energy projects.

The brightest spot for decarbonization came, not surprisingly, with the wild success of solar energy. The power industry is building more gigawatts of solar than any other type of plant, and that construction pushed solar generation up by 34%.

“We did see a record year for solar generation last year — but for that, we would be in a much worse position from an emission standpoint,” King said.

However, solar is growing very fast from a small baseline, and on a national level, it still lags behind natural gas, nuclear, coal, and wind in total generation. Without the tremendous solar build-out, utilities might have burned even more coal. But solar alone couldn’t satisfy the growing demand for electricity last year.

Looking ahead at the durability of these trends, King said, “the question is, to what extent can policy actions continue to suppress that solar growth?”

Solar installations last year rolled forward on momentum created by supportive Biden-era policies. But the second Trump administration has taken numerous actions to block or slow renewable power plant construction. If those efforts succeed in slowing the pace of solar development, and power demand and gas prices remain high, the country could be on track for more emissions increases in the years to come.