In some parts of California, the lead state on electric vehicles, utilities are facing a challenge that will eventually spread nationwide: Local grids are struggling to keep up with the electricity demand as more and more drivers switch to EVs.

The go-to solution for this type of problem among most utilities is to undertake expensive upgrades, paid for by all their customers, so that the grid can accommodate the new load.

But there’s a cheaper option: Utilities could simply make sure that the EVs that plug into their grids aren’t all charging at the same time.

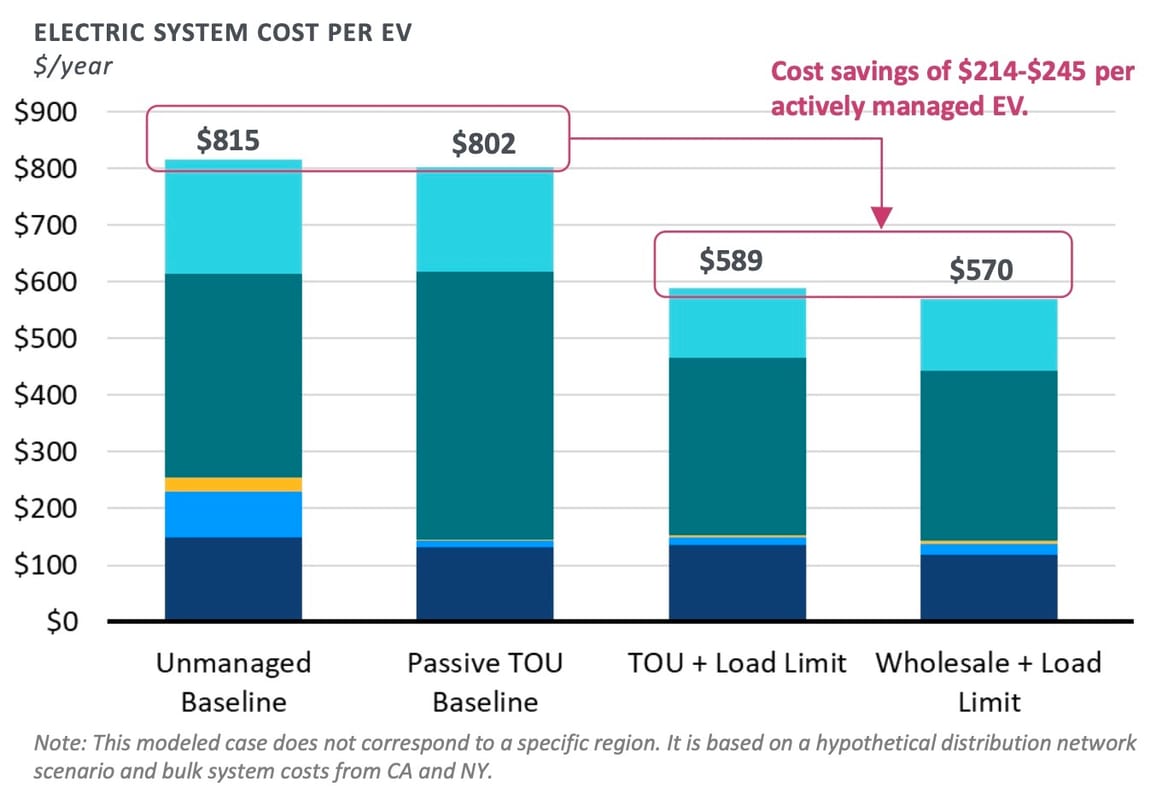

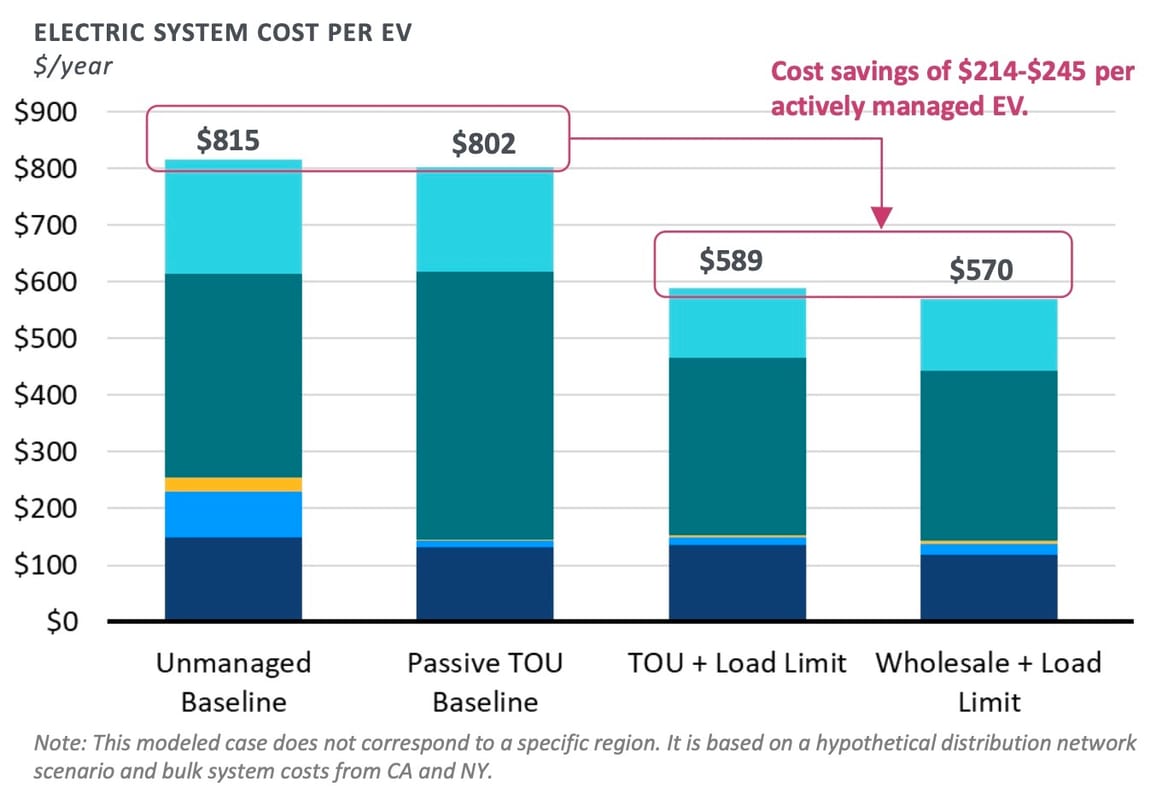

So finds a new report prepared by The Brattle Group, an energy consultancy, on behalf of EnergyHub, a company that operates virtual power plants (VPPs) for more than 170 utilities. In an analysis of 58 EV owners in Washington state, the authors found big cost benefits from “active managed charging,” the process of modulating when and how much EVs charge to minimize their impact on the grid.

It’s a crucial finding, as researchers say the approach is most effective when deployed before lots of EVs show up on utilities’ grids. Previous research has found that the cost of unmanaged charging could add as much as $2,500 per utility customer once EVs reach higher levels of penetration on utility grids. In California, that cost is already impacting utilities’ plans. Other fast-growing EV regions, including New York and Massachusetts, could soon face similar challenges.

Managed charging is a simple concept but not a simple task. To make it work, utilities have to get EV owners to enroll in managed charging programs, which requires convincing them that they won’t be left with a depleted battery when they need to drive somewhere.

Utilities also need to persuade their regulators — and their own internal grid planners — that these charging regimes are reliably relieving the local transformers, feeder lines, and substations that would otherwise be overloaded by too many EVs charging at once. If utilities can’t do that, they’ll wind up having to build new grid infrastructure anyway.

Managed charging isn’t a new idea. Utilities across the country are starting to test such programs operated by EnergyHub, Camus Energy, ev.energy, Kaluza, WeaveGrid, and other companies.

And the benefits of scaling up such programs could be major, said Akhilesh Ramakrishnan, managing energy associate at The Brattle Group. “With active managed charging, you can roughly double the capacity of the grid to host EVs,” he said.

That would help utilities contain the high and rising costs of maintaining and expanding their distribution grids, which now make up the biggest share of rapidly rising U.S. utility rates.

To achieve the savings that this approach promises, “it’s really important that the solution is implemented without damaging customers’ reliance on their cars,” Ramakrishnan said — in other words, making sure “that their cars are charged by when they need them.”

That’s where more sophisticated managed charging comes in, said Freddie Hall, a data scientist at EnergyHub. The company runs managed EV charging pilots for utilities such as Arizona Public Service and Southern Maryland Electric Cooperative, and applied similar techniques to the EV drivers in Washington state analyzed for the new report.

EnergyHub takes pains to forestall the risk of leaving EV owners without the charge they need by the time they need it, Hall said. For example, “we’ve found that some people don’t constantly update their charge-by time settings,” he said, referring to the deadline that each driver sets to have a full battery. So EnergyHub uses drivers’ past charging behaviors to forecast when they typically unplug and to make sure they’re scheduled to be fully charged by that time.

Occasionally, that requires allowing EVs to collectively pull more power from the grid than permitted under the “load limits” that utilities have set for the transformers, distribution feeders, and substations delivering it, he noted. To deal with that, EnergyHub dispatches charging in ways that minimize those overloads: “We spread out that charging to achieve a lower peak over a longer duration.”

EnergyHub’s managed charging doesn’t just limit impacts on the distribution grid, Hall said, but also co-optimizes for when power is cheaper across the grid at large. It targets times when wholesale electricity prices are low — although it will choose to forego that cheaper energy if using it would violate its local load-limit settings.

These techniques require a lot of information, making them harder to implement than time-of-use rates — the most common way that utilities try to limit EV charging loads today.

Those programs typically charge more for power at times when the grid at large is under peak demand stress, usually during late afternoons or early evenings in the summer or early mornings in the winter, and they charge less for power during off-peak times, typically late at night.

But these time-of-use rates can actually cause more grid stress than they resolve, Ramakrishnan said. That’s because they create a secondary “snapback effect” when rates change from expensive to cheap, and everyone’s EV starts charging at once.

“We’re not trying to say that time-of-use is a bad solution in general, or doesn’t work at all,” Ramakrishnan said. “At lower penetrations, there’s value in shifting EV load to move away from the time that other loads peak. But fairly quickly — when you get to 7% to 10% penetration — EVs themselves start to set the peak.”

That’s one reason why the report recommends that utilities start working on active managed charging programs before EV purchases start to overwhelm the grid. The other reason is to match the pace of how utilities plan ahead for grid investments, Hall said.

“I worked at two utilities before coming to EnergyHub. Grid planning is a multiyear-type deal,” he said. “Getting infrastructure for the distribution grid takes up to 18 or more months. Solutions like these help utilities put off some decisions for up to 10 years, if not more.”

The ability to push out grid upgrades is particularly valuable at a time when power demands are growing even as utilities are under pressure to contain costs, Ramakrishnan said. “A lot of utilities are capital constrained right now.”

At the same time, EVs represent a massive opportunity for utilities to increase electricity sales — and that could put downward pressure on the rates that all customers have to pay. That’s because regulators set those rates based on how much money utilities need to earn to cover their costs. More sales divided by fewer costs means lower rates over the long run.

At the very least, managed charging can better align EVs’ costs with their benefits, Ramakrishnan said. “One, you push the upgrade out and can save money for longer,” he said. “Two, the upgrade gets pushed out to when there are more EVs — that means there are more EVs paying for it.”