Energy storage is having a moment — but the batteries that are taking off today only have enough juice to provide a few hours of grid power. Developers technically could stack up more batteries for longer-term storage, but that gets prohibitively expensive. For a renewables-dominated grid to ride out days of poor solar production or even just an entire night, a breakthrough in cost-effective, longer-term storage is needed.

Over the last couple decades, venture capitalists have recognized this transformative possibility and heaped billions of dollars into the sector known as long-duration energy storage, or LDES. They have little to show for their efforts. The startups that haven’t gone bankrupt have built some factories and early installations, but have not built any particularly large-scale projects, at least in the U.S.

A few weeks ago, I saw something in the desert outside Reno, Nevada, that got me thinking the investors and startups may have been barking up the wrong tree all along.

Former Tesla Chief Technology Officer JB Straubel unveiled a surprising new project in June at the Tahoe campus of his lithium-ion recycling company, Redwood Materials. Instead of ripping apart old electric vehicle battery packs, his engineers arranged them across a patch of desert and hooked them up to an adjacent solar field. This assemblage now stores so much clean power that it can run a small on-site data center, rain or shine, night or day.

In other words, instead of inventing a brand-new technology tailored for long-term storage, Redwood made it way cheaper to stack enough time-tested lithium-ion batteries to accomplish that goal.

Unveiling this new business line, Straubel wasn’t just diversifying his revenue streams. He was staking claim to the long-duration storage market writ large.

“We’re confident this is the lowest-cost storage solution out there,” Straubel said. “Not only just lower than new lithium-ion batteries, but lower than compressed-air energy storage, lower than iron-air, lower than a number of these other ones that carry a little more technology risk.”

As he spoke, Straubel pointed at a bar graph depicting the costs of those types of LDES technology, as well as thermal storage, pumped-hydro storage, and flow batteries. Naturally, the chart showed his used batteries clocking in cheaper than all of them.

It’s a big claim. Second-life battery development is even newer than the LDES field; prior to Redwood, only a handful of companies, like B2U Storage Solutions and Element Energy, had built large-scale second-life storage plants, and those were just in the last few years. The sector has a lot of work to do to convince customers and financiers that the gently used battery packs can be trusted to hold up over years of service. And with new lithium-ion packs getting ever cheaper, the discount offered by used batteries may prove tenuous.

Still, Straubel’s first operating project, which holds 63 megawatt-hours of energy storage, is already bigger than any novel battery installation in the U.S. If Straubel takes this concept mainstream, it could revolutionize the arms race for long-duration storage — and radically improve the odds of running the economy on a largely renewable grid.

At the June event, Straubel essentially asserted that his band of desert engineers, in just a few months of tinkering, has outmaneuvered the researchers and companies working on long-duration for decades.

That deserves some scrutiny — but even pinpointing the costs of the competition is challenging.

“There are a lot of flavors of long-duration storage. What all of them have in common is that actual deployments have been very limited up until now,” said Pavel Molchanov, who analyzes cleantech companies for financial services firm Raymond James. “To make any clear-cut statements about which particular flavor is cheaper than any other would be quite premature.”

Redwood says its second-life battery installations cost less than $150 per kilowatt-hour today, for systems that can deliver power over 24 to 48 hours. The company’s datapoints on the prices of other battery types were drawn from BloombergNEF’s 2024 analysis of the LDES field, augmented with Redwood’s internal estimates for what a complete iron-air system would cost today, since that technology isn’t yet commercially available.

Iron-air is under development, most famously, by Straubel’s former Tesla Energy compatriot Mateo Jaramillo at Form Energy, a VC darling that’s raised more than $1.2 billion to date. Redwood calculated iron-air costs at higher than $150 per kilowatt-hour, but Form has stated its intentions to sell batteries below $20 per kilowatt-hour when its factory reaches full production scale.

It’s worth noting that not all these technologies are directly comparable, because companies design and market them at different durations based on their technical sweet spots. If a technology works especially well at, say, 12 hours duration, the company might not even sell it for 48-hour configurations.

“Part of the issue with comparing long-duration storage systems and prices is that every company will give you their price point for a different duration,” said James Frith, a longtime battery analyst now at VC firm Volta Energy Technologies. “Then you’re thinking, how do I normalize this? How do we get to a base point that is comparable amongst the technologies?”

Epistemological issues aside, Redwood accurately diagnoses that the LDES sector’s struggle to deliver real installations at super-low cost leaves an opening for new competitors.

Brand-new lithium-ion batteries aren’t economically viable at longer durations, though their limits keep expanding as battery prices fall.

“Lithium-ion storage systems with longer durations require more battery cells, making the system capital-intensive and less economically competitive compared to emerging long-duration storage alternatives,” said Evelina Stoikou, head of battery technology and supply chain research at BloombergNEF.

Pumped-hydro and compressed-air energy storage work for longer durations, but they are huge, billion-dollar infrastructure projects of the sort that don’t get built anymore in the U.S. (Canadian company Hydrostor is attempting to break that curse with a $1.5 billion, 500 MW/4,000 Mwh compressed air project in California; if it gets permits to build, it might be online by 2030.)

Flow batteries — which store energy in tanks of liquid electrolytes — have been kicking around for decades with some success in China, where they benefit from government favor. In the U.S., they’ve not gained much traction.

Meanwhile, many LDES startups have made the strategic error of designing exotic storage solutions to eke out a few more hours, under the incorrect assumption that lithium-ion would never be able to compete at four, then six, and then eight hours.

Take ESS, which has developed an iron-based flow battery since 2011: Despite leaning into “long-duration” branding, the company was selling an Energy Warehouse with a bit over six hours duration, and only this year announced a “strategic shift to the 10+ hour product.” (Its board members had to throw in more cash last month to sustain the company through that shift, and gamely agreed to forgo personal compensation for the year.)

The LDES companies most vulnerable to competition from Redwood are the ones that aren’t actually very long-duration, and which haven’t gotten big enough to make their products cheaper.

That’s not to say the other LDES contenders are left quaking in their boots.

“We’re a long way away from proof that second-life batteries are a proper utility-grade asset, capable of 20 years of daily cycling,” said Ben Kaun, who for years analyzed LDES technologies for the Electric Power Research Institute and now works for battery startup Inlyte Energy. “I don’t see an existential threat to LDES.”

The sector has even been showing signs of life, at least compared to its dismal track record from the preceding decade. Form completed its factory in Weirton, West Virginia, and broke ground on its first commercial deployment, in Minnesota, last summer. The company plans to deliver its first batteries to the project in the coming weeks, for commissioning this fall. Over in the Netherlands, a Dutch startup called Ore Energy recently installed a small 100-hour system of its own iron-air battery, based on research at the Delft University of Technology.

Flow batteries have built up considerable installed capacity in China, but that trend hasn’t gotten much coverage in English-language press, said Eugene Beh, CEO and cofounder of California-based flow-battery startup Quino Energy. His strategy is to leverage the now-mature supply chain for flow-battery equipment but to drop in an electrolyte based on quinones, commonly used in clothing dyes, instead of the more expensive vanadium that’s popular in China.

Italian startup Energy Dome has moved swiftly from demo to commercial operations with an iconoclastic design: It stores energy by compressing carbon dioxide in a controlled environment; decompressing it turns a turbine and generates electricity. After building a pilot and a commercial project in Sardinia, Energy Dome just announced an equity investment from Google for an undisclosed amount and a commitment to build its systems to power Google’s data center expansion around the world.

These more out-of-the-box LDES companies might take solace in a few limitations that second-life battery developers must overcome to mount a serious challenge.

Second-life companies take hundreds of batteries from different manufacturers, with different patterns of wear and tear, then operate them all in concert. If that was easy, more people would be doing it by now. Firms that get this wrong could start fires, and fire safety is one of the key arguments used against lithium-ion installations, both by rival technologists and the general public.

Then again, Straubel has as much experience as anyone with the inner workings of lithium-ion batteries. At Tesla, he built the nation’s leading electric-car company and a wildly successful stationary-storage business with the Powerwall and Megapack.

Then there’s the question of longevity. The batteries were pulled out of vehicles for a reason: usually due to their capacity degrading, though other problems develop with age, like higher internal resistance, which makes batteries heat up during discharge. If second-life packs need to be swapped out too frequently, it undercuts the ease and cheapness of the model.

That leaves the matter of supply. Success in second-life depends on a steady and cheap source of gently used EV packs. Here Redwood has a unique advantage, in that the company was constituted to collect the nation’s battery waste and recycle it. Straubel said Redwood was receiving less than 1 gigawatt-hour of used EV packs two years ago, and now is pulling in more than 5 GWh per year.

The available supply of used EV packs is “going to follow roughly the same curve as electric vehicle adoption, but lagging by, let’s say, 10 years,” Frith said. “So we are going to start seeing the volume of packs growing, and I think the real volumes start to kick in closer to 2030.”

Indeed, he added, the growth in volume of used EV packs could parallel the growth of demand for long-duration storage: Few customers buy it now, but many analysts expect demand to grow by the end of the decade as renewables saturate the grid.

It’s too soon to know if used EV batteries will actually wipe the floor with the more unconventional long-duration battery technologies. But the scale and price point of Redwood’s first project announces them as a force to be reckoned with in this arena.

In doing so, Redwood puts a new spin on an energy-storage maxim that venture capitalists keep forgetting, or simply ignoring: Lithium-ion always wins.

Challengers that rely on different chemistries have to build up from negligible production scale and convince customers to take a chance on a design that few people have seen before. It’s a clear uphill battle.

Lithium-ion batteries, in contrast, command an unmatched and ever-expanding scale of industrial production, mostly in China but increasingly in the U.S. too. That manufacturing juggernaut unlocks incremental gains from economies of scale and continual innovation. It also confers consumer confidence, because the technology has such a clear track record of performance.

“Compared to most experts’ predictions, the costs have gone down faster and the performance has improved faster for lithium-ion than people predicted 10 years ago,” said Jeff Chamberlain, who helped the Department of Energy license battery technology to General Motors and LG Chem back in the late 2000s, and now invests in storage technologies as CEO of Volta Energy Technologies.

Nonetheless, investors continued to bet that the streak would end, and they could own a piece of the transformational tech that would triumph for longer-term storage.

“What a lot of startups and investors are doing is assuming the LDES market will exist and it will be enormous, and they’re assuming lithium-ion won’t solve the problem,” Chamberlain said. “I believe that is a very, very bad assumption.”

Over the last decade, lithium-ion has steadily chipped away at use cases where new battery inventions were supposed to win out. New lithium-ion is starting to push into six-hour configurations and beyond, said Stoikou, from BloombergNEF. Global average pricing for turnkey grid storage averaged $165 per kilowatt-hour in 2024, per the data firm’s 2024 survey.

Now, the cost savings from reusing lithium-ion packs accelerate the chemistry’s push into the long-duration market — something that would be a big win for grid-decarbonization efforts, while delivering the LDES hopefuls yet another stinging loss.

Clarifications were made on August 6 and August 7, 2025: This story has been updated to reflect Eugene Beh’s full title and to note that Hydrostor is attempting to build a large-scale compressed air project in California.

A surge of housing development in a Boston suburb is providing evidence that natural-gas bans and strict energy-efficiency standards do not slow new construction or make it more expensive. Indeed, these guidelines can even boost the growth of affordable housing, say local advocates.

In 2024, Lexington, Massachusetts, banned gas hookups in new construction and adopted a stringent building code that requires high energy-efficiency performance. Yet these regulations have not stopped the town of roughly 34,000 from permitting some 1,100 new units of housing — 160 of which will be affordable — over the past two years.

“Opponents said, ‘It’s going to cost so much, you’re going to stop the development of affordable housing.’ But that clearly wasn’t the case,” said Mark Sandeen, a member of the town select board and the board of the Lexington Affordable Housing Trust.

As Massachusetts aims to get to net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, the state has for several years prioritized policies that encourage the transition away from fossil fuels, particularly natural gas, which heats about half of the state’s homes. In 2022, Massachusetts launched a pilot program allowing 10 communities — including Lexington — to prohibit the use of fossil fuels in new construction and major renovations. In late 2023, utilities regulators issued an order that makes explicit the state’s goal of getting off natural gas, and lays out strategies and principles for reaching this goal.

Detractors, however, have consistently argued that requiring or even heavily encouraging all-electric construction would make housing more costly and difficult to build at a time when Massachusetts is facing an acute housing shortage. In 2022, then-Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, memorably said the idea of fossil fuel bans gave him “agita,” so worried was he that such municipal regulations would suppress housing growth.

Similar battles have played out across the country, from California to New York.

There is plenty of evidence that electrified, highly efficient homes don’t need to come with a price premium.

A 2022 study by think tank RMI found that, in Boston, all-electric homes are slightly less expensive both to build and to operate than mixed-fuel homes — and that was before Massachusetts’ investor-owned utilities adopted lower wintertime rates for homes with heat pumps. In 2023, Massachusetts-based advocacy group Built Environment Plus found that building larger multifamily and affordable housing developments “net-zero ready” — that is, highly efficient and with all-electric heating — costs about 4% less up front than the conventional approach.

After Lexington changed its zoning rules in 2023 to allow more multifamily development, its energy regulations did not, as naysayers had feared, deter developers from taking advantage. The planning board has approved nine projects, ranging from a proposal to redevelop an unused commercial space into a seven-unit building, to a complex combining 312 residential units with 2,100 square feet of retail space.

The new construction will include both rental units and condos available to purchase that will, in total, increase available housing in town by 9%. Much of the new housing will be market-rate, and Lexington — where the median condo went for $915,000 in the first quarter of 2025 — is not an inexpensive place to live.

However, most of the construction driven by the new zoning is required to make 15% of its units affordable. On top of these private projects, the town has decided to develop a municipally owned property into a 40-unit affordable housing development, bringing the total number of affordable units on the horizon to about 200.

The municipal project will include four residential buildings designed to be energy-efficient and to minimize the square footage of halls and other common areas, which will reduce the cost of heating and cooling these spaces. Solar panels on the roofs will offset the electricity consumed by the building’s heat pumps, said Dave Traggorth, principal with Causeway Development, the company chosen to develop the property.

“Ultimately, what the tenant is paying for in their electric bill is really just cooking and lights,” he said. “It really reduces the utility bills for residents.”

All of these new projects — market-rate and affordable — will be prohibited from using fossil fuels to run furnaces or other appliances because of the town’s requirement that new construction be fully electric.

The town has also adopted an optional, more rigorous version of the state building code that requires new, multifamily projects over 12,000 square feet — which applies to most of those in the pipeline in Lexington — to build to passive house standards, which require a very well-sealed building envelope and dramatically reduced energy use compared to a conventionally built structures.

“This is what you can do at the local level,” said Lisa Cunningham, cofounder of climate advocacy organization ZeroCarbonMA.

While Lexington is a particularly active town, the other nine communities that have banned fossil fuels in new construction have all reported that the rules have posed no obstacle to development, Cunningham said. Restrictive zoning and antidevelopment sentiment among residents are much more pressing problems, she said.

For the eventual residents, the benefits go beyond the knowledge that their homes are helping cut emissions. Homes designed to passive house standards use far less energy than those that are conventionally built, creating ongoing savings for homeowners and tenants, and have been found to generally have better indoor air quality. When the power goes out, these well-sealed buildings can keep interior temperatures comfortable for days.

It is no accident that residential developers were ready to jump when opportunities opened up in a town with stringent efficiency and electrification rules. Massachusetts has been laying the groundwork for years, said Lauren Baumann, director of sustainability and climate initiatives for the Massachusetts Housing Partnership, a nonprofit that works to expand affordable housing.

“There has been this deliberate effort to develop an ecosystem to support this kind of construction,” she said.

In 2019, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center awarded $1.73 million in grants to eight affordable, multifamily projects to help accelerate the adoption of passive house standards in multifamily construction by demonstrating that the approach makes financial sense. That same year, the state’s energy-efficiency program administrator, Mass Save, launched an initiative offering money to multifamily projects for feasibility studies, energy modeling, and analyses of post-construction energy performance.

These incentives gave architects and contractors a lower-risk way to become familiar with a new approach to building. And familiarity, in this case, bred knowledge, skills, and enthusiasm.

“Those early project pilots really did give people the experience they needed in order to feel comfortable,” Baumann said. “We just saw an explosion of interest.”

Traggorth has seen this evolution in his work. Five years ago, he said, if he approached a contractor to discuss building to passive house standards, he was often greeted with confusion. Now, “every contractor that’s building multifamily has a couple of projects that have been passive house certified,” he said. “They have learned their lessons.”

Alicia Brown, director of the Georgia Bright Coalition, wants people to know that the $7 billion Solar for All program is starting to bring affordable solar power to her home state — even as the Trump administration threatens to kill it.

With the $156 million Solar for All grant the coalition won last year, it’s installing no-cost rooftop solar for low-income homeowners and expanding a two-year-old pilot program that offers low-cost solar and battery installations for thousands more residences. It’s also planning to back community solar projects and is helping finance solar and batteries at churches that promise to use the cheap power to lower utility bills for disadvantaged households and provide shelter during grid outages.

Now this program and others being actively developed by state agencies, municipalities, tribal governments, and nonprofits that received Solar for All grants are in jeopardy. The Environmental Protection Agency, which administers the grant program, is preparing to send letters to all 60 awardees informing them that their funding will be terminated, according to news reports this week citing anonymous sources.

The National Association of State Energy Officials (NASEO), a group representing the state agencies responsible for managing a large chunk of Solar for All funding, also widely circulated an email warning that the EPA could be on the brink of ending the program.

“We do not have any additional details or validation of the news that has been reported,” NASEO President David Terry wrote in the email, which was shared with Canary Media. “Yet, the information received yesterday comes from a credible source.” (NASEO did not immediately respond to requests for comment.)

Cutting Solar for All funding would be a mistake, said Michelle Moore, CEO of Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit Groundswell. Over the next five years, the program promises to deliver more than $350 million in annual electric bill savings to more than 900,000 low-income and disadvantaged households — desperately needed relief in a time of high and rising utility costs.

And the more than 4 gigawatts of solar power the program aims to bring online, much of it backed up by batteries, could help utilities across the country meet growing demand at a time when the Trump administration and Republicans in Congress have undermined the policies supporting clean energy growth.

Groundswell is using its $156 million Solar for All grant to launch the Southeast Rural Power Program, open to municipal utilities and rural cooperatives across eight Southeastern states to develop more than 100 megawatts of distributed solar and battery projects.

Those projects could cut electricity bills in half and improve local resilience for more than 17,000 households. That’s a vital source of new grid capacity for a region facing unprecedented growth in demand for electricity, Moore said.

“This country is short on power right now. We need every electron we can get,” she said. Terminating Solar for All at this stage would equate to “this administration raising electricity bills for more than 1 million families. Now is not the time.”

Solar for All, an initiative of the Inflation Reduction Act’s $27 billion Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund (GGRF), had its funding frozen in January as part of a broader attack on Biden-era climate and environmental programs.

In the face of court orders declaring these freezes unlawful, in February the EPA reopened funding for Solar for All and other congressionally mandated programs. Since then, Georgia Bright hasn’t experienced any difficulty accessing its Solar for All funds, Brown said.

But because of the way that reimbursement is structured under the program, the coalition and other Solar for All awardees need the EPA to continue to make funds available to cover ongoing expenses. “It’s not like there’s $156 million in our bank account,” she said.

Other EPA-administered programs haven’t fared so well. EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin is still blocking $20 billion in funding for the broader GGRF program and is appealing federal court orders to release the money. EPA is also facing a class-action lawsuit demanding it release the billions of dollars in environmental justice block grants it terminated.

Solar for All has been something of a bright spot amid these roadblocks, Brown said. In recent months, grantees like Georgia Bright have begun rolling out their first rounds of funds.

In May, Vermont’s Department of Public Service announced $22 million in grants for low-income-housing solar projects. Last month, Michigan’s Office of Climate and Energy announced eight projects, ranging from an agrivoltaics installation near a municipal airport to solar panels on a multifamily building serving low-income seniors. And the Nevada Clean Energy Fund, a nonprofit green bank, last month announced its first project — nearly $1 million to help a sober living facility in Reno install rooftop solar.

“It seems like this program has bipartisan support — it certainly does in Nevada — because there’s a big need for it. Reducing energy costs is important, particularly in our economic environment,” said Kirsten Stasio, CEO of the Nevada Clean Energy Fund. “If an affordable housing owner needs to pay more for their utility bills, it means they are paying less on supportive services for their tenants.”

The EPA’s initial funding freeze was concerning, said Chris Walker, head of national policy and programs for Grid Alternatives, the country’s largest free solar installation nonprofit and prime contractor for more than $300 million in Solar for All grants. Still, “we were confident we were on a solid legal footing to continue the work, and continued staffing and contracting processes, with a bit of nervousness about what might be coming,” he said.

Now, as Grid Alternatives prepares to launch its first Solar for All projects, he said, “We’re in capacity-building mode and compliance mode.”

Rumors that the EPA plans to terminate Solar for All have been swirling for months, said Jillian Blanchard, vice president of climate change and environmental justice at Lawyers for Good Government, a nonprofit coalition of attorneys, law students, and activists that’s challenging other EPA funding cuts.

“There are many, many Solar for All grantees doing everything in their power to move things forward,” she said. “But EPA is not making it easy.”

Cutting off Solar for All grants would almost certainly draw a legal challenge, given that the funds were awarded by the EPA last year under contracts that cannot be terminated without cause.

“If leaders in the Trump administration move forward with this unlawful attempt to strip critical funding from communities across the United States, we will see them in court,” Kym Meyer, litigation director for the Southern Environmental Law Center, told Canary Media. “We have already seen the immense good this program has done on the ground, and we won’t let it be snatched away to score political points.”

Complicating matters, Blanchard said, is the megalaw passed by Republicans in Congress last month, which officially repealed statutory authority for the GGRF and rescinded unspent funds from the program. The law, however, does not claw back obligated funds, she said.

An EPA spokesperson declined to say if the agency intends to terminate Solar for All grants, but told Canary Media in a Tuesday email that “with the passage of the One Big Beautiful Bill, EPA is working to ensure Congressional intent is fully implemented in accordance with the law.”

Blanchard said that language in the megalaw clearly indicates that the intent of lawmakers was to retain obligated spending from the GGRF. “If EPA does this unilaterally, it will be pulling a complete bait and switch on the American people, increasing utility bills, and flouting congressional intent,” she said.

Terminating Solar for All funds wouldn’t just harm the communities burdened by high and rising electricity prices, said Sachu Constantine, executive director of nonprofit advocacy group Vote Solar. It would also hurt utilities struggling to meet rising electricity demand.

A growing body of research shows that low-income neighborhoods and communities of color face greater risks of power outages and grid failures, partly due to decades of underinvestment in the grids that serve them. Solar for All “targets frontline underinvested communities, which means it’s targeting weak spots on the grid,” Constantine said. “It’s infrastructure in the right places for the right people.”

And solar and batteries are the right technology to solve the problem, he contended. Solar panels and lithium-ion batteries are not only the cheapest and fastest-to-deploy sources of new grid supply; they’re also capable of lowering peak electricity demands that drive the lion’s share of utility costs, by serving as virtual power plants.

“When we don’t have to deploy the most expensive peaker [power plants], when we can better utilize the distribution lines, we’re saving the cost for everyone,” he said. “We’re taking the entire system and making it run better.”

That’s a role Georgia Bright wants to play with its community-benefits solar program, Brown said. Last month, the Georgia Public Service Commission approved a long-term resource plan from Georgia Power, the state’s biggest utility, which has been criticized by environmental and consumer advocates for extending the life of aging coal-fired power plants and opening the door to building up to 8.5 gigawatts of new fossil gas–fired turbines.

But the plan also includes a pledge from Georgia Power to develop a pilot program that will seek up to 50 megawatts of solar and battery capacity from customers. Georgia Bright worked to get that program included in the utility’s plan, Brown said — and it plans to use its community-benefits solar program to help churches, nonprofits, businesses, and multifamily housing properties install the solar and batteries to participate in it.

“I think we’ll hit the 50 megawatts pretty quickly — and the commission is open to raise that limit,” she said. “They recognize if you need to serve all this new load, you can’t wait on natural gas plants that have a five-year backlog to get a turbine.”

Groundswell’s Southeast Rural Power Program offers similar fast-start options for utilities struggling to meet growing demand for power, Moore said. “It’s a straightforward way to work across the Southeast in very diverse states with very diverse needs.”

SECO Energy, a rural electric cooperative in Florida, is one of the potential partners for Groundswell’s new program. About 80,000 of SECO’s roughly 250,000 customers are low and moderate income, and “Solar for All checks a lot of the boxes for us to serve that segment of the population,” SECO CEO Curtis Wynn said.

“We’re in a high-growth area, and during the last two or three days, the heat index was over 100 degrees — it puts a strain on our system,” he said. “If there’s a way we can use grant dollars to buy down the cost of generation today that’s going to remain stable in the next 20 years in a rising-cost environment, that’s a huge advantage.”

Figure 1. Heat Content in the Top 700 Meters of the World's Oceans, 1955–2023

This figure shows changes in heat content of the top 700 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2023. Ocean heat content is measured in joules, a unit of energy, and compared against the 1971–2000 average, which is set at zero for reference. Choosing a different baseline period would not change the shape of the data over time. The lines were independently calculated using different methods by government organizations in four countries: the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute (MRI/JMA). For reference, an increase of 1 unit on this graph (1 × 1022 joules) is equal to approximately 17 times the total amount of energy used by all the people on Earth in a year (based on a total global energy supply of 606 exajoules in the year 2019, which equates to 6.06 × 1020 joules).4

Data sources: CSIRO, 2024;5 IAP, 2024;6 MRI/JMA, 2024;7 NOAA, 2024

Web update: June 2024

Figure 2. Heat Content in the Top 2,000 Meters of the World’s Oceans, 1955–2023

This figure shows changes in heat content of the top 2,000 meters of the world’s oceans between 1955 and 2023. Ocean heat content is measured in joules, a unit of energy, and compared against the 1971–2000 average, which is set at zero for reference. Choosing a different baseline period would not change the shape of the data over time. The lines were independently calculated using different methods by government organizations in three countries: the United States’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute (MRI/JMA). For reference, an increase of 1 unit on this graph (1 × 1022 joules) is equal to approximately 17 times the total amount of energy used by all the people on Earth in a year (based on a total global energy supply of 606 exajoules in the year 2019, which equates to 6.06 × 1020 joules).4

Data sources: IAP, 2024;6 MRI/JMA, 2024;7 NOAA, 20248

Web update: June 2024

When sunlight and energy trapped by greenhouse gases reach the Earth’s surface, the world’s oceans absorb some of this energy and store it as heat. This heat is initially absorbed at the surface, but some of it eventually spreads to deeper waters. Currents also move this heat around the world. Water has a much higher heat capacity than air, meaning the oceans can absorb larger amounts of heat energy with only a slight increase in temperature.

The total amount of heat stored by the oceans is called “ocean heat content,” and measurements of water temperature reflect the amount of heat in the water at a particular time and location. Ocean temperature plays an important role in the Earth’s climate system—particularly sea surface temperature (see the Sea Surface Temperature indicator)—because heat from ocean surface waters provides energy for storms and thereby influences weather patterns.

Increasing greenhouse gas concentrations are trapping more energy from the sun. Because changes in ocean systems occur over centuries, the oceans have not yet warmed as much as the atmosphere, even though they have absorbed more than 90 percent of the Earth’s extra heat over the last half-century,1 and even as the rate of ocean heat uptake has doubled since 1993.2 If not for the large heat-storage capacity provided by the oceans, the atmosphere would warm more rapidly.3 Increased heat absorption also changes ocean currents because many currents are driven by differences in temperature, which cause differences in density. These currents influence climate patterns and sustain ecosystems that depend on certain temperature ranges.

Because water expands slightly as it gets warmer, an increase in ocean heat content will also increase the volume of water in the ocean, which is one of the major causes of the observed increases in sea level (see the Sea Level indicator). For all these reasons, ocean heat content is one of the most important indicators tracking the causes and responses of a changing climate.

This indicator shows trends in global ocean heat content from 1955 to 2023. Measurement data are available for the top 2,000 meters (nearly 6,600 feet) of the ocean, which accounts for nearly half of the total volume of water in the world’s oceans. This indicator also shows changes representative of the top 700 meters (nearly 2,300 feet) of the world’s oceans, where much of the observed warming has taken place. The indicator measures ocean heat content in joules, which are units of energy.

Organizations around the world have calculated changes in ocean heat content based on measurements of ocean temperatures at different depths. These measurements come from a variety of instruments deployed from ships and airplanes and, more recently, underwater robots. Thus, the data must be carefully adjusted to account for differences among measurement techniques and data collection programs. Figure 1 shows four independent interpretations of essentially the same underlying data for the top 700 meters of the ocean, and Figure 2 shows three independent interpretations for the top 2,000 meters of the ocean.

Data must be carefully reconstructed and filtered for biases because of different data collection techniques and uneven sampling over time and space. Various methods of correcting the data have led to slightly different versions of the ocean heat trend line. Scientists continue to compare their results and improve their estimates over time. They also test their ocean heat estimates by looking at corresponding changes in other properties of the ocean. For example, they can check to see whether observed changes in sea level match the amount of sea level rise that would be expected based on the estimated change in ocean heat.

Data for this indicator were collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and other organizations around the world. The data were analyzed independently by researchers at NOAA, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, China’s Institute of Atmospheric Physics, and the Japan Meteorological Agency’s Meteorological Research Institute.

1 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2021). Climate change 2021—The physical science basis: Working Group I contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (V. Masson-Delmotte, P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S. L. Connors, C. Péan, S. Berger, N. Caud, Y. Chen, L. Goldfarb, M. I. Gomis, M. Huang, K. Leitzell, E. Lonnoy, J. B. R. Matthews, T. K. Maycock, T. Waterfield, O. Yelekçi, R. Yu, & B. Zhou, Eds.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896

2 IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). (2019). Summary for policymakers. In The ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate: Special report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157964.001

3 Levitus, S., Antonov, J. I., Boyer, T. P., Baranova, O. K., Garcia, H. E., Locarnini, R. A., Mishonov, A. V., Reagan, J. R., Seidov, D., Yarosh, E. S., & Zweng, M. M. (2012). World ocean heat content and thermosteric sea level change (0–2000 m), 1955–2010. Geophysical Research Letters, 39(10), 2012GL051106. https://doi.org/10.1029/2012GL051106

4 IEA (International Energy Agency). (2021). Key world energy statistics 2021. www.iea.org/reports/key-world-energy-statistics-2021

5 CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization) (2024). Update to data originally published in Domingues, C. M., Church, J. A., White, N. J., Gleckler, P. J., Wijffels, S. E., Barker, P. M., & Dunn, J. R. (2008). Improved estimates of upper-ocean warming and multi-decadal sea-level rise. Nature, 453(7198), 1090–1093. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07080

6 IAP (Institute of Atmospheric Physics). (2024). Update to data originally published in Cheng, L., Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J., Boyer, T., Abraham, J., & Zhu, J. (2017). Improved estimates of ocean heat content from 1960 to 2015. Science Advances, 3(3), e1601545. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1601545

7 MRI/JMA (Meteorological Research Institute/Japan Meteorological Agency). (2024). Global ocean heat content. www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/kaiyou/english/ohc/ohc_global_en.html

8 NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). (2024). Global ocean heat and salt content: Seasonal, yearly, and pentadal fields. www.nodc.noaa.gov/OC5/3M_HEAT_CONTENT

At the end of June, California Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) signed into law AB 130, a sweeping bill that aims to make it easier to build housing, reforms that many lawmakers and experts agree are long overdue given the state’s severe housing crisis.

But one provision could needlessly slow the state’s progress on its climate and clean energy goals, according to advocates. The law pauses updates to state and local building codes — the mandatory construction standards meant to ensure that new buildings are safe and energy efficient — for the next six years.

Buildings account for a quarter of California’s carbon pollution. And the state’s building standards, which are normally revised once every three years, have been a powerful decarbonization tool. The latest statewide energy code, already finalized, takes effect Jan. 1, 2026, and encourages developers to build all-electric homes with both heat pumps and heat-pump water heaters — super-efficient, zero-emissions appliances that are safer than gas-fired options. In addition to updating codes, California has eliminated subsidies for new gas lines.

These regulations are working; “California is an electrification-forward state,” said Sean Armstrong, managing principal of Redwood Energy, a design firm specializing in net-zero, all-electric affordable housing development. In 2023, 80% of line extension requests by builders to utilities Pacific Gas & Electric and San Diego Gas & Electric were electric-only, according to the California Energy Commission, the agency responsible for developing the building energy codes. The commission expects that the majority of new houses built under the latest code will be all-electric.

Now, though, the state will skip a scheduled 2028 residential code update, blocking it from pushing builders to go further to cut emissions. Starting Oct. 1 this year, the new law will also prevent local jurisdictions from updating their own, more ambitious building standards, known as reach codes.

These could include measures not yet enacted in the state rules, such as encouraging heat pumps for multifamily buildings, mandating all-electric renovations, and requiring that broken central air conditioners be replaced with heat pumps that can both warm and cool spaces. That last idea is an inexpensive way to decarbonize heating, according to Matt Vespa, senior attorney at nonprofit Earthjustice.

Seventy-four local governments in California have passed reach codes that encourage or require all-electric new construction. With the pause on updates looming, San Francisco is now racing to get an all-electric requirement for major renovations on the books before the Oct. 1 deadline.

AB 130 does allow for some exceptions that could let local governments implement stricter building requirements even after the cutoff date.

The law permits the state commission and local governments to update building codes in emergencies to protect health and safety. Perhaps the climate emergency will qualify, said Kelly Lyndon, cochair of the advocacy alliance San Diego Building Electrification Coalition.

Cities and counties can also adopt updates that are necessary to carry out greenhouse gas emissions reduction strategies spelled out in their state-mandated general plans. These road maps must have been adopted by June 10, 2025, and code updates can’t ban gas.

“At least one of these exceptions is going to work for folks who want to make further progress on climate,” said Merrian Borgeson, director of California policy with the Natural Resources Defense Council’s Climate & Energy Program. “Unfortunately … [AB 130] makes it more complicated and creates more red tape.”

Vespa pointed out that many jurisdictions may be able to take advantage of the exception for preexisting aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Among the 482 city plans, 409 mention “greenhouse gas” — an indicator that local leaders are pursuing emissions cuts. The phrase also shows up in 52 of 58 county general plans.

Sacramento’s general plan, for example, stresses “a continued focus on improving the performance of both new and existing buildings.” A local code update to swap old air conditioners with heat pumps could fit within AB 130’s exemption, Vespa said.

But it’s too soon to say who might try the strategy first. “Some jurisdictions are really looking towards their legal experts to interpret [the exception language],” said Madison Vander Klay, senior manager of government affairs at the nonprofit Building Decarbonization Coalition.

But even with its exclusions, the moratorium “is a big problem for emissions, affordability, and cost savings,” Vander Klay said.

Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas (D) and Assemblyperson Nick Schultz (D), who authored the initial standalone bill to pause building codes, AB 306, championed the idea as a way to help solve California’s housing affordability crisis and spur rapid recovery after the wildfires that torched areas of Los Angeles County in January. That bill eventually got folded into AB 130.

“California home prices are double the national average, and the rent is too damn high. So many folks cannot afford to live in California,” Schultz said on the Assembly floor in April. “This pause … will provide stability and certainty in the housing construction market by temporarily freezing the standards by which people need to meet to construct their home.”

It’s unclear whether the bill will actually make homes more affordable, though. “Building codes have never been what drives high costs in California — certainly not the energy code,” Borgeson said.

A 2015 study conducted by the University of California LA for Pacific Gas & Electric backs that up; the authors noted that they couldn’t find a statistically significant relationship between California’s energy-efficiency code and home construction costs.

“There isn’t a lot of evidence that waiving codes helps affordability,” Vander Klay said. “The building codes overall are required [by law] to be cost-effective.” Any up-front costs must be outweighed by savings.

The standards have delivered, sparing Californians more than $100 billion in avoided energy costs over the last five decades, according to the Energy Commission. The code that takes effect next year is expected to net more than $4.8 billion in savings over 30 years.

Research also shows that building all-electric homes is typically faster and cheaper than building those with gas. A 2019 analysis by energy consultancy E3, for example, estimated that building a new all-electric home in most parts of California costs about $3,000 to $10,000 less than building a home that’s also equipped with gas. Similarly, a 2022 study by the New Buildings Institute found that constructing an all-electric single-family home in New York costs about $8,000 less than a home with gas. A UC Berkeley team used these and other findings to conclude in an April report that the most cost-effective way to rebuild after the LA fires is likely all-electric.

With the moratorium, the commission will have to skip the 2028 residential code cycle. That omission could result in tens of millions of dollars in lost utility bill savings for households, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition. Notably, the commission will be able to work on the following code update, so it can take effect as planned in 2032.

In the wake of AB 130, the Building Decarbonization Coalition’s Vander Klay is urging the Legislature to reauthorize California’s successful cap-and-trade program to support home electrification by making heat pumps and other decarbonizing tech more affordable. “There is still an opportunity … this year for the state to look at carving out funding to provide incentives,” she said.

In passing AB 130, state lawmakers took aim at rules that they contend stifle development. Underpinning this strategy is a notion popularized by a recent book, “Abundance.” Authors Ezra Klein of The New York Times and Derek Thompson, contributing writer at The Atlantic, make the case that well-intentioned but overly protective regulations can foster scarcity — in this case, of housing — and thus interfere with leaders’ ability to deliver on the promises of a better life.

But Vander Klay argues that lawmakers should view strong building codes as a way to help create abundance. “Abundance is this idea that we should all have access to housing, we should all be able to afford our energy bills … we should all be able to have access to clean air and clean water and healthy homes,” Vander Klay said.

Clean energy technologies like heat pumps are part of an abundant, safer, more climate-resilient future, she noted. “We have building codes as a tool to support building what we need safely and quickly and affordably.”

The humble streetlight doesn’t look like a particularly attractive target for theft. But in Los Angeles, a mind-boggling 27,000 miles of copper wire connect those lights to the power grid — and thieves are tearing that wire out at an alarming rate. Public employees can’t keep up with repairs, leaving frustrated neighborhoods in the dark for months on end.

The sun-drenched city has recently discovered a promising new solution: It’s swapping out traditional streetlights for solar-powered versions that are not attached to the larger power system and thus have no copper wire to steal. Instead, the new lights are equipped with batteries that fill up on solar energy during the day and discharge it after dusk falls.

“It’s been tremendously successful,” said Miguel Sangalang, executive director and general manager of LA’s Bureau of Street Lighting.

While copper-wire theft isn’t a new plight for LA, it’s become more prevalent in recent years as rising prices have made it more lucrative to sell the stolen metal. In the last decade, theft and vandalism have jumped from representing just a few percent of the Bureau of Street Lighting’s service requests to 40% today, according to a spokesperson for the department. Since 2020, the city has spent over $100 million repairing such damage. On Reddit, residents complain of “pitch black” neighborhoods that feel unsafe.

The city isn’t about to replace all of its more than 220,000 streetlights with solar. So far, it’s only deployed around 1,100 of the new fixtures, and plans to install at least 400 more this fiscal year. The Bureau of Street Lighting is still figuring out its long-term strategy, but for now, it’s focused on rolling out solar lights where they can immediately do the most good: areas with lots of theft.

“[We’re] testing it in incremental steps,” Sangalang said. “But we see ourselves going into it much harder and much faster in the near future.”

Other U.S. cities are thinking along the same lines. Clark County, home to Las Vegas, began testing solar streetlights last summer after dropping more than $1.5 million over two years to fix vandalized lights. St. Paul, Minnesota, decided to install the city’s first solar streetlights this year, fed up after spending over $2 million in 2024 on repairs only for thieves to strike again days later. San Jose, California, which had about 1,000 streetlights out due to copper theft in early July, is currently planning a pilot, pending funding availability.

These are small-scale experiments, but they still reduce planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions by introducing more clean energy into major cities. One of the solar lighting companies that LA is working with estimates that deploying 10 of its sun-powered streetlights in Europe would cut carbon emissions by 60 metric tons over four decades — the same pollution footprint as seven flights around the Earth.

Inspired by a suggestion from a field electrician, LA began testing off-grid solar lights in 2022 with $200,000 in grants from the city’s innovation fund. In early 2024, the city rolled out its first concentrated, large-scale deployment of 106 solar lights in the Van Nuys neighborhood — a hotspot for theft that is located far from the Bureau of Street Lighting’s headquarters downtown.

“We’d spend two hours on the road trying to do a repair if we had to go back and forth,” Sangalang said.

The goal in Van Nuys was to create a “maintenance-free zone,” said a spokesperson for the Bureau of Street Lighting. It’s working: In a year and a half, the department hasn’t had to deal with a single instance of damage related to theft and vandalism. Among community members, “the sentiment continues to be that they’re great and that we need to see more of them in the city,” said LA Councilmember Imelda Padilla, a Democrat who represents Van Nuys.

With that track record, the city has since rolled out hundreds more solar lights in the Watts, Boyle Heights, and Historic Filipinotown neighborhoods.

“This is one of those things where, across the board, whether you care about the environment or not, lighting is the best deterrent to crime, right?” Padilla said. “It makes it so that families and single women and children can enjoy the Southern California weather late into the night.”

For the record, LA is also taking other steps to deter copper-wire theft, such as encasing wire enclosures in concrete, replacing copper with less valuable aluminum wiring, and standing up a special police task force.

What sets solar lights apart are their benefits unrelated to theft, Sangalang said: The systems cut the city’s energy bills and can stay lit during blackouts. Plus, they each take only about 30 minutes to install on average (after prep work), since the new lighting fixture, solar panel, and battery pack are often simply attached to an existing streetlight pole.

The big catch with solar streetlights has always been their up-front cost. According to the LA Bureau of Street Lighting, a single solar- and battery-equipped lighting unit can cost around $3,250 — a huge jump from the $300 to $500 price tag for standard equipment.

It’s not easy to sell city leaders stressed about budget shortfalls on the idea of spending thousands of taxpayer dollars replacing perfectly fine grid-connected streetlights with their solar counterparts. But copper-wire theft is completely upending the calculus.

A single repair to address copper theft can cost between $750 and $1,500, Sangalang explained, meaning that “in a place where I would have had to go repair two, maybe three times, the solar light itself would have paid for itself in that same time frame.”

Despite the momentum toward solar streetlights, infrastructure-scale deployment is still just beginning in the U.S., said Hocine Benaoum, CEO of Texas-based Fonroche Lighting America, one of the companies supplying LA with solar lights.

City governments in this country are often risk-averse when it comes to new technology. Fonroche, which was founded in France in 2011, lights highways and communities around the world, but its municipal customers in the U.S. typically insist on first trying out just a handful somewhere like the back parking lot of a public works building, he said. Once they find out that works, the lights often get tested on a slightly more public site like a dog park or a pickleball court before — finally — a city feels comfortable installing them on residential streets.

“We were lighting whole countries in Africa, highways, whatever,” Benaoum said with a smile. “And in the U.S., you meet with the city manager and public works, and they tell you, ‘OK, yeah, we love your product. Let’s put it in the dog park.’ So there are a lot of dogs that are happy with Fonroche in the U.S.”

In LA, Sangalang is gaining confidence in the technology, although sun-fueled fixtures don’t yet meet the city’s brightness standards for major streets. Other areas aren’t good candidates for solar lights because tall buildings block the sun for much of the day.

Off-grid solar lights also can’t support the EV chargers and telecom equipment that LA hooks up to grid-connected lights, according to the Bureau of Street Lighting. While Sangalang is considering the potential of solar-powered lights that also feed into the grid, he said that technology is less developed.

“[Solar lights are] a great tool in the toolbox for the larger system,” Sangalang said, “understanding that you must use different tools for different places.”

After a decade of urging from clean energy advocates, utility Duke Energy finally has a plan to let its North Carolina customers access detailed information about their electricity use.

Approved by state regulators on July 16, the program has backing from the state customer advocate and the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association. But critics say unresolved aspects, including the size of the fee Duke charges third parties for data access, will determine its success or failure.

The Duke plan is a step toward solving a common problem for utility customers, large and small: They don’t have ready access to complete, granular information about their energy use or an easy way to share that data with others. That can complicate decarbonization efforts for a range of consumers, from households that want rooftop solar to cities aiming to shrink their carbon footprints.

The city of Charlotte, for instance, owns one of the world’s busiest airports, which it aims to power entirely with clean energy by the end of the decade. But dozens of private entities within the facility have electricity accounts, so city officials don’t know exactly how much power the entire complex uses — or how much renewable energy they need to meet their target.

At the other end of the size spectrum, individuals considering energy-efficiency improvements, rooftop solar panels, or switching to a heat pump often don’t have a full picture of when their energy use peaks or which appliances gobble up the most power.

Limited access to energy-usage data is hardly confined to Duke, said Michael Murray, who cofounded the nonprofit Mission:data after realizing that getting usage data in his home state of California was like pulling teeth.

“California actually had the first policy on this in the country in 2013,” Murray said, thanks in part to his group’s advocacy. Now, Mission:data engages with utilities commissions in about 10 states every year. “To date, we’ve gotten policies in place for about 41 million electric meters in the country. Not all the policies are perfect,” he said. Referencing the freshly approved Duke plan, he added, “this is certainly one of those.”

Like North Carolina-based advocates, Mission:data has been cajoling Duke for better data access for years. And though the group declined to endorse the proposal put forward in November by the utility, in-state advocates, and others, Murray doesn’t question the rationale of those who backed it.

“It does make some progress for the communities who are interested in energy benchmarking,” he said.

That’s especially welcome under the Trump administration, which has created countless new barriers to adopting clean energy. With the November proposal now blessed by regulators, communities and individuals alike are better equipped to take advantage of what federal climate programs still exist — and to decarbonize in general.

“There are still some [climate programs] that are absolutely out there that are moving forward,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory and legal counsel for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association.

For example, North Carolina’s federally funded $156 million Solar for All program, called EnergizeNC, is intended to help low-income customers put rooftop panels on their homes. Improved data access will enable them to right-size those installations.

“[The state is] still dotting a lot of I’s and crossing T’s on program design,” Blumenthal said, “so this data access capability could be very useful.”

Individual customers contemplating solar or high-efficiency appliances like heat pumps can still access a 30% federal tax credit, though only until the end of this year.

Aggregate data that shows the combined energy use of multiple utility customers can help cities like Charlotte administer a new state law that allows commercial building owners to borrow money for renewable energy and energy-efficiency upgrades and pay it back on their property tax bills.

“We do have a lot of large buildings with multiple tenants,” Aaron Tauber, Charlotte’s sustainability analyst, said last fall when the access program was first proposed. “I’m just really excited for these building owners to really — for the first time — gain an understanding of how their buildings are using energy.”

Granular details about energy use at 15-minute intervals are also helpful for customers as Duke and other utilities across the U.S. experiment with time-of-use rates and virtual power plants. Virtual power plants are networks of rooftop solar, home batteries, and other distributed energy resources that utilities can manipulate to support grid reliability at large, while time-of-use rates are electricity charges that vary over the course of the day to nudge energy use to periods of low demand.

“Duke has been making this big push to time-of-use rates,” Blumenthal said, noting that the utility just got a pilot program approved to encourage customers to charge their EVs overnight, when the grid is typically less strained.

But certain features of the new data access program remain unsettled, and the devil could be in those details, says Murray.

Customers can receive two years of their own individual data for free. But Murray worries that regulators will allow Duke to charge exorbitant access fees for aggregated data or to third parties, which would undercut the program.

“Authorized third parties will be charged ‘commission-approved fees’ — but these will be determined later, and could be anything,” he said. “Maybe if the fees are $3, this is fine, but what if they’re $100 or $200?”

In the latter case, third parties would be more likely to resort to “screen-scraping,” a practice that’s illegal at worst and inefficient at best, whereby energy service contractors obtain usage data by combing through customers’ online account profiles with their usernames and passwords.

What’s more, Murray said, “third parties must meet Duke’s ‘cybersecurity risk assessment,’ which is unknown and could be unilaterally changed at Duke’s whim, creating business uncertainty. There is also the risk of Duke discriminating against third parties and accepting some while rejecting others.”

Time is of the essence. Duke has pledged to implement the rules within 18 months — a promise underscored by the recent order from the Utilities Commission.

Asked when Duke planned to submit proposed fees and cybersecurity standards, Duke spokesperson Logan Stewart said it “will file a plan with the Commission within 30 days of the order, which details the … plan for implementing the data sharing functionality.”

That means a more fleshed-out proposal could come in mid-August, and Mission:data will be watching.

“This is not the utilities’ proprietary business data that they can hide from disclosure,” Murray said. “This is the customer’s data. They own their data. And they should be able to exchange that with whoever they want, even if the utility is not happy about that.”

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Just under three years ago, the Inflation Reduction Act went into law and generated tens of billions of dollars’ worth of investment in domestic manufacturing of clean energy technologies. President Donald Trump has turned that wave into a ripple.

Since Trump took office in late January, companies have paused, canceled, or shuttered 26 different manufacturing projects that would have brought $27.6 billion in investment and nearly 19,000 jobs to communities across America, according to new data from The Big Green Machine, a project from Wellesley College.

Over that same time period, 29 new projects were announced for a total of just $3 billion.

Under the Biden administration, companies pledged well over $100 billion in factory investment, thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act’s incentives for manufacturers and for project developers and people to buy American-made solar panels, batteries, electric vehicles, and more. The cleantech manufacturing surge was so significant that it pushed overall manufacturing construction to heights not seen in decades.

Areas represented by Republicans in Congress stand to gain the most from this factory boom. More than 80% of the clean-energy manufacturing investment announced as of February would flow to Republican-led districts; over 70% of the jobs would go to these places.

But under Trump’s new “big, beautiful” law, the future of those projects is less certain.

The law did not repeal tax credits for most clean-energy manufacturers, but it will eat away at their customer base by scrapping subsidies for wind and solar developers. It also introduced strict anti-China stipulations to the manufacturing tax credit, which could be a headache for companies to comply with, depending on how the Treasury Department decides to enforce the rules.

These factors, in addition to the increasingly volatile business environment in the U.S., do not bode well for the clean-energy manufacturing boom regaining momentum in the near term. Nor do Trump’s beloved tariffs hold much promise as a way forward. Previous attempts to boost domestic solar-panel manufacturing via tariffs alone have failed, and experts say Trump’s measures will actually drive costs up for U.S.-based producers.

That’s not to say cleantech manufacturing is now a lost cause in the U.S. — some solar producers, for example, are feeling optimistic. But what’s increasingly clear is that the short-lived boom times are over, and any manufacturing success stories from this point on will be in spite of the federal government rather than because of its generous support.

Offshore wind leasing is effectively dead in the U.S. following a Trump administration order issued this week.

Large swaths of U.S. waters that had been identified by federal agencies as ideal for offshore wind are no longer eligible for such developments under an Interior Department statement released Wednesday.

In the four-sentence statement, Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) said the U.S. government is “de-designating over 3.5 million acres of unleased federal waters previously targeted for offshore wind development across the Gulf of America, Gulf of Maine, the New York Bight, California, Oregon, and the Central Atlantic.”

The move comes just a day after Interior Secretary Doug Burgum ordered his staff to stop “preferential treatment for wind projects” and falsely called wind energy “unreliable.” Analysts say that offshore wind power can be a reliable form of carbon-free energy, especially in New England, where the region’s grid operator has called it critical to grid stability. It also follows the Trump administration’s monthslong assault on the industry, which has included multiple attacks on in-progress projects.

The outlook was already grim for new offshore wind leasing activity following President Donald Trump’s executive order in January that introduced a temporary ban on the practice. Wednesday’s announcement makes that policy more definitive. Wind power advocates say it will erase several years of work from federal agencies and local communities to determine the best possible areas for wind development.

“My read on this is that there is not going to be any leasing for offshore wind in the near future,” said a career employee at the Interior Department, who Canary Media granted anonymity so they could speak freely without fear of retribution.

Figuring out the best spot to place offshore wind is an involved undertaking. The proposed areas start off enormous and, according to the Interior staffer, undergo a careful, multiyear winnowing process to settle on the official “wind energy area.” Smaller lease areas are later carved out of these broader expanses.

Take the process for designating the wind energy area known as “Central Atlantic 2,” which started back in 2023 and is now dead in the water.

The draft area — or “call area” — started out as a thick belt roughly 40 miles wide and reached from the southernmost tip of New Jersey to the northern border of South Carolina, according to maps on BOEM’s website. Multiple agencies, including the Department of Commerce, the Department of Defense, and NASA, then provided input on where that initial area might have been problematic. NASA, for example, maintains a launch site on Virginia’s Wallops Island and in 2024 found that nearby wind turbines could interfere with the agency’s instrumentation and radio frequencies.

The winnowing didn’t stop there. By 2024, according to BOEM’s website, its staff was hosting in-person public meetings from Atlantic City, New Jersey, to Morehead City, North Carolina, to gather input from fishermen, tourism outfitters, and other stakeholders. Under a wind-friendly administration, a final designation and lease sale notice would have likely been released this year or by 2026, based on a timeline posted to BOEM’s website.

But the Trump administration is no friend to offshore wind.

Trump officials have repeatedly targeted wind projects by pulling permits and even halting one wind farm during construction. Last month, Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” sent federal tax credits to an early grave, requiring wind developers who want to use the incentives to either start construction by July 2026 or place turbines in service by the end of 2027. The move is particularly devastating for offshore projects not already underway. Currently, five major offshore wind farms are under construction in the U.S., and when they come online, they will help states from Virginia to Massachusetts meet their rising energy demand with carbon-free power.

Wednesday’s order halts all work on Central Atlantic 2 and similar areas, like one near Guam, and also revokes completely finalized wind energy areas with strong state support. One example is in the Gulf of Maine, where Gov. Janet Mills, a Democrat, has been a fierce advocate for the emerging renewable sector.

These wind energy areas could hypothetically be re-designated by a future administration or the policy reversed, according to the Interior Department employee. Still, in the best case, that means developers will have to wait several more years for new lease areas to become available, further slowing down an industry whose projects already take many years to go through permitting and construction.

Plans are in the works to build America’s first new aluminum smelters in nearly half a century. The two facilities, slated to go online in Oklahoma and possibly Kentucky in the coming years, would dramatically boost domestic production of the versatile metal if completed as planned.

But for that to happen, they will first have to secure a steady supply of electricity, at a time when AI data centers and other industrial facilities are competing fiercely for a share of the country’s limited power resources, and as the grid is strained by surging demand.

The smelters proposed by Emirates Global Aluminium and Century Aluminum would be energy hogs. Each plant is expected to produce about 600,000 metric tons of aluminum each year, requiring enough electricity annually to power the state of Rhode Island. That’s because the process of converting raw materials into primary aluminum requires hundreds of megawatts of power running at near-constant rates.

For the economics to pencil out for either facility, that power will need to be cheap. And it will need to be produced from carbon-free sources, like wind or solar, for the aluminum they produce to be more competitive on the global market, which increasingly favors low-carbon metal.

Unfortunately for American aluminum producers, both clean and affordable power are only getting harder to come by.

Electricity demand in the U.S. is rising faster than supply is forecast to grow, which is pushing up prices. Aging grid infrastructure and slow permitting timelines have long delayed the build-out of new power generation. Now the Trump administration and GOP-led Congress are creating additional financial and legal headwinds for wind, solar, and battery storage projects — the only resources that can be built fast enough to meet demand in the near term.

“With clean energy tax credits going away, we can reasonably expect the cost of electricity to go up in all markets,” said Annie Sartor, the aluminum campaign director for Industrious Labs, an advocacy organization. “That’s just profoundly challenging to aluminum facilities that are looking for electricity … especially in a moment when there’s a rush on electricity nationally.”

The deepening power crunch represents a major roadblock in the quest to reshore U.S. manufacturing.

The Trump administration recently raised tariffs on aluminum and steel imports from 25% to 50% to bolster the business case for producing primary metals domestically. It has also preserved a crucial award for Century Aluminum’s smelter that was issued in the final days of the Biden administration. In January, the Department of Energy awarded Century a grant of up to $500 million as part of a federal industrial decarbonization program, much of which has since been defunded.

But to successfully kick-start an American aluminum renaissance, the government and utilities will also need to make larger long-term investments in the nation’s ailing electricity sector, and develop tools that allow smelters to not just take power from the grid, but to help it run more smoothly, experts say.

“Ultimately, this is about energy,” said Matt Meenan, vice president of external affairs for the Aluminum Association, a trade group that supports an “all-of-the-above” approach to electricity sources.

“And until you crack that nut,” he added, “I think we’re going to have a hard time becoming fully self-sufficient for primary aluminum in the U.S.”

Aluminum companies worldwide produced 73 million metric tons of primary, or virgin, aluminum in 2024. The lightweight metal is used to make products as varied as fighter jets, power cables, soda cans, and deodorant. It’s also a key component of clean energy technologies like electric vehicles, solar panels, and heat pumps.

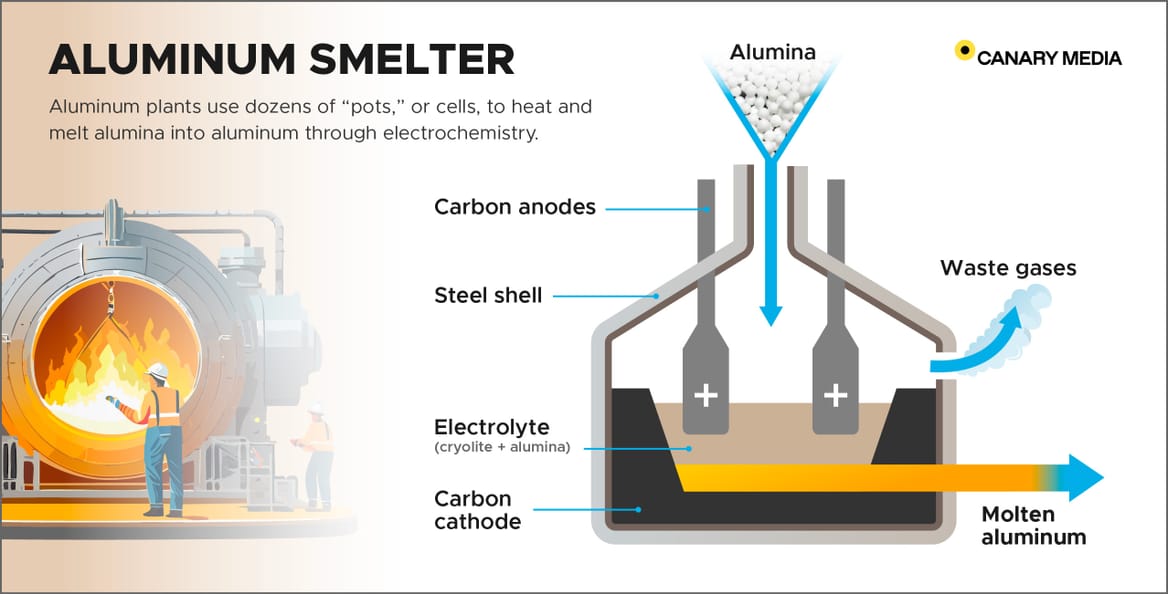

Producing aluminum contributes about 2% of total greenhouse gas emissions every year. The majority of those emissions come from generating high volumes of electricity — often derived from fossil fuels — to power smelters. The smelting process involves dissolving powdery white alumina in a scorching-hot salt bath, then zapping it with electrical currents to remove oxygen molecules and make aluminum.

The United States was once one of the world’s top producers of primary aluminum. In 1980 — the last year a new smelter was built — the nation had 33 operating facilities, many of which relied on cheap power from public hydropower plants. But then industrial electricity rates began to rise after the federal government restructured energy markets in 1977.

Deregulation was “the single most important factor leading to the near total demise of the primary aluminum industry,” the Aluminum Association said in a recent white paper entitled “Powering Up American Aluminum.” The U.S. industry’s downward spiral accelerated further after China joined the World Trade Organization in 2001, leading to a glut of inexpensive Chinese aluminum on the global market.

Today, just four American smelters remain operational. In 2024, they produced an estimated 670,000 metric tons of primary aluminum, or less than 1% of global production. The U.S. mainly makes secondary aluminum from scrap metal, which totaled over 5 million metric tons last year. While secondary production is growing, it can’t fully replace the need for strong and durable primary aluminum.

“There’s always going to be a role for primary aluminum,” Meenan said. “And we do think having smelters here is really important.”

Century Aluminum and Emirates Global Aluminium both say their new smelters will mark a new beginning for the U.S. primary-aluminum sector. The two facilities would together nearly triple the nation’s primary-aluminum capacity when they come online, potentially around 2030.

Century Aluminum first unveiled plans for its smelter in March 2024, after the Biden-era Department of Energy launched a $6 billion initiative to modernize and decarbonize America’s industrial base. As part of the award process, Century said its Green Aluminum Smelter could run on 100% renewable or nuclear energy and would use energy-efficient designs, making it 75% less carbon-intensive than traditional smelters.

At the time, the Chicago-based manufacturer identified northeastern Kentucky as its preferred location for the smelter, though the company was also evaluating sites in the Ohio and Mississippi river basins. More than a year later, Century still hasn’t picked a final project site for the $5 billion smelter — because it hasn’t yet locked down its power supply.