It’s been a difficult year for clean energy in America. President Donald Trump entered office in January and promptly stopped the transition away from fossil fuels and toward solar, wind, and batteries in its tracks. Right?

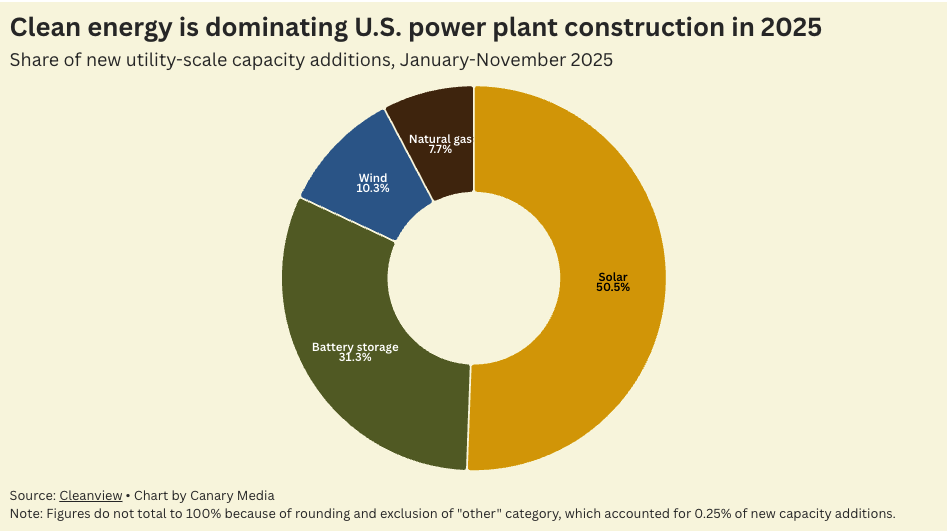

Not quite. In fact, for all of Trump’s paeans to “beautiful, clean coal” and to natural gas, it’s clean energy that has once again led the way this year. Through November, 92% of new power capacity added to the grid in 2025 came in the form of solar, wind, or storage, according to Cleanview analysis of U.S. Energy Information Administration data shared with Canary Media.

That’s in line with figures from recent years. In 2024, 96% of U.S. capacity additions were carbon-free.

This year, solar alone accounted for half of new capacity added to the grid through November, while storage made up 31%. Despite Trump’s all-out assault on wind energy — and his pledge that no “windmills” would be built during his term — the energy source has so far accounted for more gigawatts of new electricity than gas turbines have.

It’s worth noting that December is typically the busiest month for new energy deployments in the U.S., so these numbers will look a bit different when the full-year data comes in. It’s also possible that clean-energy deployments are artificially high right now as developers race to complete projects before Trump’s restrictions on lucrative tax credits kick in. And, overall, fossil fuels still generate a much larger share of U.S. electricity than renewables do — even if solar and wind are closing that gap.

Still, the figures underscore the warnings made by energy experts, policymakers, and advocates: The Trump administration is playing with fire by trying to limit the development of solar, battery, and wind energy right when electricity demand is rising at its fastest rate in decades.

These are the quickest sources of energy to deploy. Meanwhile, gas turbines face a supply-chain crunch that is both driving up the cost of some new power plants and making it near impossible to build enough gas facilities to meet new demand, even if climate concerns weren’t a factor.

Should Trump administration policies succeed in drastically slowing down solar, batteries, and wind next year, it’ll only make the mounting energy-affordability crisis even worse.

This year in energy has been an absolute blur. We started with President Donald Trump’s declaration of a federal energy emergency, saw the gutting of clean-energy tax credits, and finished with an Election Day where affordability took center stage.

Now, with 2025 almost behind us, let’s rewind and revisit the 10 stories that defined this year.

Trump declares an energy emergency

On his first day in office, Trump set course for a total revamp of the American energy landscape. Step one: Citing rising power demand to declare a national emergency on energy, all while freezing funds for clean energy programs. Trump proceeded to use that “emergency” to prop up fossil fuels — more on that below.

Interior Department halts — then restarts — Empire Wind construction

The Trump administration’s laser focus on killing offshore wind became impossible to ignore when, in April, it ordered Empire Wind to stop work. The turbines off New York had only been under construction for a few weeks, and the stop-work order was eventually lifted. The story essentially repeated itself a few months later with the nearly complete Revolution Wind project.

The Department of Energy forces coal plants to stay open

In May, the U.S. DOE cited its “emergency” to force Michigan’s J.H. Campbell coal plant to run past its retirement date. That order has been extended twice, and so far, the plant has racked up more than $100 million in costs for utility customers. The DOE later ordered other soon-to-retire fossil-fueled plants to keep operating.

The “Big, Beautiful Bill” guts clean energy incentives

On the Fourth of July, Trump signed into law the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which was big but certainly not beautiful for clean energy. The legislation took an axe to the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act and its tens of billions of dollars in funding for the energy transition.

Nuclear gets a federal boost

At least one carbon-free power source has been exempt from Trump’s hit list. The administration has elevated nuclear power as a solution to rising power demand, including by promoting the restart of some retired nuclear plants. It’s also poured funding into the development of small modular reactors and other next-generation technologies.

Batteries have a stellar year, again

Energy storage was also spared the Trump administration’s wrath, though tariffs and “foreign entity of concern” rules will likely weaken the industry. Still, the U.S. installed 12.9 GW during the first three quarters of the year, already beating 2024’s total installed capacity of 12.3 GW.

EVs’ record quarter and collapse

Federal tax credits for EV purchases went out with a bang. In the three months before their expiration at the end of September, the U.S. saw nearly 440,000 new EVs hit the roads, smashing the past quarterly sales record. But now that we’re in a post-incentive world, EV sales have sunk.

Blue-state climate grants slashed

One of the Trump administration’s biggest attacks on clean energy came in October, when the DOE moved to claw back nearly $8 billion in grants for climate and energy projects, largely in states that voted for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris in the 2024 election. The Justice Department later admitted in a court filing that those states’ politics put them in the administration’s crosshairs.

Data center opposition reaches a fever pitch

Data centers and their potential to use huge amounts of energy became a top concern in 2025, especially in hot spots like Virginia and Texas. State legislatures introduced close to 200 bills regarding data centers this year, with about 50 aimed at incentivizing their development, and others targeting their impact on the environment and on electricity costs for other consumers.

Energy affordability defines state elections

Democrats swept this year’s few statewide elections, many of which centered on rising energy prices. Both New Jersey Gov.-elect Mikie Sherrill and Virginia Gov.-elect Abigail Spanberger campaigned on promises to tackle spiking energy costs, and the two Democrats who won seats on the Georgia Public Service Commission said they’d push to build more clean, cheap energy.

Ford trades EV ambitions for battery storage

From electrifying its bestselling F-150 to building a massive manufacturing complex in Tennessee, Ford once aspired to lead the EV transition. That all changed this week as the company announced it will incur nearly $20 billion in charges to extricate itself from its EV investments. That Tennessee facility, known as BlueOval City, will build gas-powered trucks in lieu of electric models, and production of the F-150 Lightning will end.

But as Ford backs away from EVs, it’s entering a new market. The automaker will repurpose its Kentucky EV battery facility to build grid-scale batteries instead. As Canary Media’s Julian Spector put it, Ford is essentially copying Tesla’s game plan to expand into storage — but without an EV stronghold to fall back on, it could be a risky move.

Another coal plant restart — and more to follow?

As you read above, the Trump administration’s coal plant restarts are a huge piece of its fossil-fuel-boosting agenda, and we got two more updates on that front this week. On Tuesday, the DOE ordered Unit 2 of TransAlta’s Centralia, Washington, coal power plant to stay open for the next 90 days. TransAlta has been planning since 2011 to shutter the facility, and was prepared to do so this month to comply with a Washington state law prohibiting coal burning that takes effect next year.

A similar situation may soon play out in Indiana, Canary Media’s Kari Lydersen reports. Two coal plants in the state are supposed to close this month, but their owners have told regulators they anticipate orders from the Trump administration will keep the facilities running.

Also this week: The U.S. House passed a bill that will broaden the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s authority to keep power plants online past their scheduled retirements.

Not so fast: The U.S. House passes the SPEED Act, an attempt at revamping the National Environmental Policy Act to hasten energy project permitting, but the bill faces a big hurdle in the Senate: opposition from climate-hawk Democrats. (Inside Climate News)

The sun is setting: Solar companies face a “mad rush” of customers looking to get panels before federal tax credits expire, leading to installation delays that could cause many hopeful buyers to miss out on the incentives. (The Verge)

Can you dig it? A Colorado coal town prepares for the closure of its nearby power plant by building an industrial park that aims to attract businesses by offering low-cost geothermal heating and cooling. (Canary Media)

Fusion fight: China pulls ahead in its race with the U.S. to prove and commercialize fusion energy technology, largely because it’s devoting far more resources to the effort. (New York Times)

Keeping renewables rolling: Tribal nations look to loans and philanthropy to keep building planned clean energy projects after the Trump administration revokes the Solar for All program and other federal funding. (Utility Dive)

Planning committee: A New Hampshire program that deploys experts to help small towns plan for a transition to clean energy inspires a federally funded nationwide pilot. (Canary Media)

Winter woes: The National Energy Assistance Directors Association predicts U.S. home heating prices will rise an average of 9.2% this winter compared to last — about three times the rate of inflation — thanks to increasing gas and electricity prices and cold conditions. (New York Times, news release)

The Georgia Public Service Commission on Friday approved a controversial plan that will allow the state’s biggest utility to commence one of the largest new fossil-fuel buildouts in the country — a move that critics fear will raise utility bills for most Georgia residents over the coming years.

The last-minute settlement was approved unanimously by the five commissioners, all Republicans. The vote came just weeks before two of those commissioners are set to be replaced by Democrats who won upset victories in the November election by running on the issue of energy affordability.

Back in November, staff at the PSC recommended that the commission allow Georgia Power to build only about one-third of the nearly 10 gigawatts of new gas-fired power plants and batteries the utility had requested. Friday’s decision instead gives it the go-ahead to move forward on building the full total.

The utility has justified that scale by pointing to forecasts of booming electricity demand due to new data-center construction. In recent weeks, however, even Georgia Power has reduced its data-center demand projections. And across the state and the country, concerns are rising that the boom in artificial intelligence that is driving data-center investments may be a bubble about to burst.

That’s why PSC staff deemed the utility’s full buildout plan too risky — and why energy experts and consumer and environmental advocates oppose it. Should Georgia Power build all of that infrastructure while data-center demand fails to materialize, its customers would be forced to pay higher bills for the unnecessary power plants.

“It is a massive financial gamble,” said Jennifer Whitfield, a senior attorney at the Southern Environmental Law Center, one of several groups protesting Georgia Power’s gas-heavy buildout plan. “The bottom line is that we don’t need this much energy based on the data that’s been provided.”

The PSC staff expect the plan to raise average household utility bills by about $20 per month, or possibly more if gas prices rise or data-center demand fails to show up, according to testimony from November. Those costs would be layered on top of six rate hikes since late 2022 that have already increased average residential bills by $43 per month, and which helped propel the two incoming Democratic commissioners to victory in November.

Georgia Power can expect to profit handsomely from the commission’s decision. The utility revealed in a Securities and Exchange Commission filing last week that the plan would allow it to invest $16.3 billion in “company-owned projects” — capital investments on which the utility earns a guaranteed rate of return.

To avoid passing extra costs onto consumers, Georgia Power would need gigawatts’ worth of data centers to be built and to continue buying electricity for decades.

Right now, it’s highly uncertain whether those data centers will ever show up.

“[O]nly a fraction of the requested capacity is backed by data center customers that have signed contracts for electric service, and even less have signed contracts covered by the protections contemplated in the Commission’s new rules and regulations,” the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy and Sierra Club wrote in a briefing filed with the commission. “With no data center customer committed to pay for most of the capacity Georgia Power is requesting for the entirety of the assets’ lifetimes, ratepayers will inevitably be on the hook.”

PSC staff in November testified that only about 3.1 gigawatts of Georgia Power’s buildout should be approved right away, based on the number of data centers that have executed contracts with the utility. It also proposed allowing about 4.3 gigawatts more on condition that additional data centers sign definitive contracts by March 2026.

Indeed, PSC staff’s forecasts of demand growth between now and 2031 were far lower than Georgia Power’s: about 6 gigawatts less under a “lower large-load materialization assumption,” and about 4 gigawatts less under a “greater large-load materialization case.”

Utilities and regulators across the country are struggling to manage similar mismatches between the unprecedented boom in proposed data centers and the increasing uncertainty that those plans will come to fruition.

When the new Democratic commissioners take office next month, it’s unclear whether they’ll be able to adjust the plan or rein in costs.

Foes of the plan are pressing commissioners to use their authority to force Georgia Power to update its load-growth forecasts and report on changing costs for the power plants it plans to build, and to retract approval for spending plans that may no longer be justified by growing demand.

But Whitfield noted that Friday’s vote by the commission authorizes Georgia Power to begin charging customers for the expenses it incurs to build and procure the resources approved by the plan.

“If in the future the commission were to modify its certification order — which it could — Georgia Power would still be able to recover any costs it incurred up to that point,” she said.

It’s also unclear whether the settlement agreement will force Georgia Power to follow through on its public pledges to limit the impact of its data center–driven investments on everyday customers, Whitfield said. Her group filed a motion earlier this week asking the commission to order Georgia Power to provide more information about its plan to use revenue from data centers and other large customers to put “downward pressure” on rates for typical residential customers.

“There are so many loopholes in the financial assurances that staff tried to achieve when it entered into this stipulation,” she said. “The end result is nearly meaningless for a typical Georgia Power customer … The reality is, we just don’t have any reassurance that all of us aren’t going to be on the financial hook for it.”

In the waning days of Governor Phil Murphy’s tenure, New Jersey officials unveiled an updated Energy Master Plan that calls for 100% clean electricity by 2035 and steep reductions in climate pollution by midcentury. Since 2019, the state has used the first version of the plan as the backbone of its climate strategy, promising reliable, affordable, and clean power.

The blueprint lands at a moment when delivering on all three goals is increasingly in doubt.

While the second Trump administration rolls back federal clean-energy support, PJM Interconnection, the regional grid operator that serves New Jersey and a dozen other states, struggles to manage surging electricity demand from artificial intelligence data centers.

“The Energy Master Plan is a statutorily required report to chart out New Jersey’s energy future,” said Eric Miller, who leads the Governor’s Office of Climate Action and the Green Economy. While not binding, it is the state’s official roadmap to attain its climate goals.

Miller’s office and the state Board of Public Utilities developed the plan with public input and help from outside consultants.

Under the plan, New Jersey is betting heavily on utility-scale solar and battery storage. State modeling envisions total solar capacity climbing to about 22 gigawatts by 2050, which is four times today’s roughly 5 gigawatts of installed solar. On paper, it would be enough to supply nearly all the state’s current households over a year. To get there, the plan assumes adding about 750 megawatts of new solar each year from 2026, roughly double the pace of solar construction in 2024.

The plan’s release follows a governor’s race in which energy costs dominated, and voters chose U.S. Rep. Mikie Sherrill, a Democrat who campaigned on preserving Murphy-era climate targets, over Jack Ciattarelli, a Republican who argued for a slower transition.

“Voters sent a clear message that clean energy is the most cost-effective path forward and the smartest long-term investment,” said Ed Potosnak, head of the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters and a local council member in Franklin Township.

The plan lands as New Jersey enters what Miller calls the “load-growth era.”

For roughly two decades, electricity demand in PJM’s footprint, which stretches from New Jersey to Illinois, was flat or falling as aging power plants retired and efficiency improved. That trend has flipped because of data centers.

“What we saw in 2024 into ’25, and I think what we’re going to see for the next 15 years, is a scenario where demand on the electric grid is growing,” Miller said.

For years, New Jersey spent billions subsidizing hundreds of thousands of electric vehicles and thousands of buildings to electrify. Now, Miller said, “some of the techniques for greenhouse gas reductions are going to have to kind of meet the moment,” by taking a more proactive role in engaging with PJM or by filling in the dearth in clean energy incentives caused by the Trump administration.

The recent PJM capacity auctions have added billions of dollars in costs for customers across the region. This showed up as a 20% jump in summer electricity bills in New Jersey this year, which became a hot campaign issue during its recent gubernatorial race.

“The wholesale price of electricity is determined by PJM and federal policy, and then also the price of natural gas,” said Frank Felder, an energy economist who has advised regulators. “New Jersey can’t do much about that.”

Participating in a fast-track rulemaking process that PJM initiated to address data center–driven demand, outgoing governor Murphy joined other governors in proposing that data center developers bring their own power generators in exchange for quicker permit processing.

PJM seeks to decide which proposals to pursue this month and file them with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission by the end of the year.

Layered on top of PJM’s turmoil are decisions coming from Washington.

Experts repeatedly pointed to President Donald Trump’s second-term moves to strip away clean-energy tax incentives from the Inflation Reduction Act and to impose new tariffs on imported solar panels and wind equipment. They say those steps have raised costs and driven off developers.

Potosnak called it “Trump’s clean energy ban” and said the administration’s opposition to offshore wind “derailed the best chance we had to get massive amounts of offshore wind going that would have begun lowering our utility rates this year.” Several major Atlantic projects, including those planned off New Jersey’s coast, have been canceled or delayed.

Offshore wind “was a big piece of trying to get to 100% clean electricity by 2035,” Felder said. With new contracts unlikely for several years, he warned that New Jersey could be “back at basically square one” by the end of the decade.

Even so, Felder and others urged caution against writing off renewables entirely. Robert Mieth, a Rutgers University researcher who studies power systems, noted that offshore wind is well established in Europe and that, with or without U.S. manufacturing, “there will be access to competitive and affordable renewable technology from other countries.”

In the meantime, state officials point to progress in areas they can influence more directly.

Miller noted that New Jersey has gone from roughly 20,000 plug-in vehicles in 2018 to about 270,000 today, after lawmakers set clear targets and funded incentives and chargers.

The state’s “nation-leading solar program,” he said, is “primarily state-incentivized, primarily state-funded,” and it can keep expanding — albeit more slowly now — even as federal tax credits expire.

“The cheapest energy is the energy you don’t have to make,” Potosnak said, citing efficiency programs, rooftop and warehouse solar, and batteries on parking lots that “drive down utility costs for families and businesses” while cutting pollution.

For all its detail, the Energy Master Plan is not binding.

“The Energy Master Plan does not have the force of law,” Miller said. It has been “very informative,” he added, but “it is not a legal requirement that we follow it exactly.”

Gov.-elect Sherrill will determine how closely New Jersey hews to the map. Neither she nor her opponent had any role in shaping the modeling, Miller said, and the plan was not written with a particular “political future” in mind. Instead, Miller said, the Murphy administration hopes the incoming governor will treat it as “a very useful modeling exercise” or a guide.

Advocates are already trying to lock some of those targets into a statute. Potosnak’s group is backing a lame-duck bill that would incorporate the state’s 2035 goal of 100% clean energy — currently in place from a 2023 Murphy executive order — into state law.

If it passes, he said, it would give residents and environmental groups the right to sue if future administrations fall short and send a signal to investors that New Jersey’s direction will not change with every election.

At the start of next year, companies that make and buy energy-intensive commodities like steel and aluminum will enter the era of CBAM — the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism.

CBAM is a first-in-the-world policy by the European Union that charges fees on imports based on how much planet-warming pollution was produced in their manufacturing. On Jan. 1, 2026, the carbon tariff will officially take effect, raising costs for European businesses that source products from dirty facilities abroad.

The policy is part of the EU’s broader effort to drive the decarbonization of heavy industries in the 27-member bloc as well as globally. It’s already having a ripple effect, with other countries considering adopting their own carbon-pricing schemes and international firms investing in cleaner technologies to make their exports more enticing to Europe.

Here’s what to know as the landmark policy goes into effect.

In 2005, the EU launched the Emissions Trading System, the first scheme in the world to limit greenhouse gas emissions from power plants and industrial facilities. The ETS caps the total amount of carbon pollution that each operator is allowed to spew. The companies can then buy allowances that give them the right to generate 1 metric ton of CO2-equivalent. The idea is that making it costlier to pollute will incentivize businesses to clean up their operations.

Until now, however, the ETS has given what experts call a “free pass” to producers of certain trade-exposed commodities. Manufacturers argued that raising the costs of producing goods in Europe would make their industries less competitive on the global market. It could also push key customers, including European automakers, to import cheaper materials from countries without stringent climate policies — a phenomenon known as “carbon leakage.”

As the EU phases out these free passes, CBAM is designed to plug such a leak.

“It doesn’t make sense that you basically ask your own producers to produce in a certain way, to be as clean as possible, or else ask them to pay a price, and then let others — competitors from outside Europe — bring in their products and then compete unfairly,” Mohammed Chahim, the European Parliament’s lead negotiator on the carbon border fee, said on the Energy Policy Now podcast earlier this year.

The EU officially finalized CBAM’s rules in May 2023. Later that year, a “transitional phase” began for importers of goods from six carbon-intensive sectors: aluminum, cement, electricity, fertilizers, hydrogen, and iron and steel. Companies had to begin filing quarterly reports listing the direct and indirect carbon emissions of those products.

On Dec. 31, that phase will end, kicking off the “definitive period.”

Starting next month, in addition to tracking emissions, importers will pay a fee on covered products like steel rods, metal wiring, and ammonia. Initially, the fee will be a small percentage of the average quarterly price of CO2 allowances under the ETS — though participants could pay less, or nothing at all, if the exporting country has a similar carbon-pricing scheme in place. Over eight years, the CBAM tariff will gradually increase to represent 100% of the weekly average allowance price.

At the same time, the EU will wind down the special treatment it’s given to trade-exposed industries under the regional cap-and-trade scheme, requiring European manufacturers to gradually pay more for their facilities’ emissions.

The free allowances were “always viewed as a bit of a black mark on Europe’s decarbonization ambitions,” said Trevor Sutton, who leads the program on trade and the clean energy transition at Columbia University’s Center on Global Energy Policy. European regulators have billed CBAM as a “necessary component” to meeting the region’s climate goals — a way to curb industrial emissions without endangering its economy, he added.

To start, the rules will only apply to importers that bring in more than 50 metric tons of goods every year. According to the EU, this threshold excludes roughly 90% of importers, who are mainly small and medium-sized businesses, but still captures around 99% of emissions from CBAM-covered goods, since large manufacturers represent the bulk of industrial imports.

CBAM has dominated global discussions on climate policy and trade in recent years. But the regulation itself is surprisingly narrow in scope. Targeted products only make up 3% of EU imports from countries outside the bloc. And the carbon footprint of those goods collectively represents about 0.31% of global greenhouse gas emissions in 2022, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Still, “it’s a topic that inspires intense emotions,” Sutton said.

Critics, including Europe’s trade partners in the Global South, have argued that the carbon tariff amounts to protectionism — an excuse to shut out foreign competition — and “green imperialism,” since Europe is unilaterally making decisions that affect producers abroad. Mozambique, for instance, sends 97% of its aluminum exports to the EU, leaving it especially exposed.

Manufacturers within the EU have also pushed back against CBAM and the related decline in free CO2 allowances, claiming that the measures put companies at a competitive disadvantage in global markets and will inflate costs for producers. Last week, the head of French aluminum producer Constellium urged Europe’s regulators to “eradicate” CBAM altogether. Importers and their suppliers have also expressed frustration at the onerous and confusing requirements involved with tracing and reporting emissions, Sutton said.

Even so, some of the EU’s key trading partners are responding to CBAM’s signals. Since the measure passed, countries like Brazil and Turkey have introduced domestic carbon-pricing policies. The United Kingdom is set to implement its own Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism starting in 2027. China, for its part, has started shipping steel made using hydrogen to Italy — a move experts say could set the stage for increasing Chinese green-steel exports.

Sutton said that CBAM “has helped drive a conversation and elevated the salience of carbon pricing” in other countries, while also setting “a foundation for decarbonization of European industry.”

Colorado just set a major new climate goal for the companies that supply homes and businesses with fossil gas.

By 2035, investor-owned gas utilities must cut carbon pollution by 41% from 2015 levels, the Colorado Public Utilities Commission decided in a 2–1 vote in mid-November. The target — which builds on goals already set for 2025 and 2030 — is far more consistent with the state’s aim to decarbonize by 2050 than the other proposals considered. Commissioners rejected the tepid 22% to 30% cut that utilities asked for and the 31% target that state agencies recommended.

Climate advocates hailed the decision as a victory for managing a transition away from burning fossil gas in Colorado buildings.

“It’s a really huge deal,” said Jim Dennison, staff attorney at the Sierra Club, one of more than 20 environmental groups that advocated for an ambitious target. “It’s one of the strongest commitments to tangible progress that’s been made anywhere in the country.”

In 2021, Colorado passed a first-in-the-nation law requiring gas utilities to find ways to deliver heat sans the emissions. That could entail swapping gas for alternative fuels, like methane from manure or hydrogen made with renewable power. But last year the utilities commission found that the most cost-effective approaches are weatherizing buildings and outfitting them with all-electric, ultraefficient appliances such as heat pumps. These double-duty devices keep homes toasty in winter and cool in summer.

The clean-heat law pushes utilities to cut emissions by 4% from 2015 levels by 2025 and then 22% by 2030.

But Colorado leaves exact targets for future years up to the Public Utilities Commission. Last month’s decision on the 2035 standard marks the first time that regulators have taken up that task.

The commission’s move sets a precedent for other states working to ditch fossil fuels from buildings even as the federal government eliminates home-electrification incentives after Dec. 31. Following Colorado’s lead, Massachusetts and Maryland are developing their own clean-heat standards.

Gas is still a fixture in the Centennial State. About seven out of 10 Colorado households burn the fossil fuel as their primary source for heating, which accounts for about 31% of the state’s gas use.

If gas utilities hit the new 2035 mandate, they’ll avoid an estimated 45.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gases over the next decade, according to an analysis by the Colorado Energy Office and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. They’d also prevent the release of hundreds more tons of nitrogen oxides and ultrafine particulates that cause respiratory and cardiovascular problems, from asthma to heart attacks. State officials predicted this would mean 58 averted premature deaths between now and 2035, nearly $1 billion in economic benefits, and $5.1 billion in avoided costs of climate change.

“I think in the next five to 10 years, people will be thinking about burning fossil fuels in their home the way they now think about lead paint,” said former state Rep. Tracey Bernett, a Democrat who was the prime sponsor of the clean-heat law.

Back in August, during proceedings to decide the 2035 target, gas utilities encouraged regulators to aim low. Citing concerns about market uptake of heat pumps and potential costs to customers, they asked for a goal as modest as 22% by 2035 — a target that wouldn’t require any progress at all in the five years after 2030.

Climate advocates argued that such a weak goal would cause the state to fall short on its climate commitments. Nonprofits the Sierra Club, the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project, and the Western Resource Advocates submitted a technical analysis that determined the emissions reductions the gas utilities would need to hit to align with the state’s 2050 net-zero goal: 55% by 2035, 74% by 2040, 93% by 2045, and, finally, 100% by 2050.

History suggests these reductions are feasible, advocates asserted.

“We’re recommending targets that put us on a technology-adoption curve — a trajectory that’s been seen over and over again,” said Ramón DC Alatorre, senior program manager at the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project. “There’s a tremendous amount [of] mature technology available today in order to be able to meet these targets.”

Heat pumps, for example, have a track record of holding their own even in Denver’s deepest freezes. Some companies are devising ways to bring installation costs way down. And the state is making the tech more affordable via a federally funded rebate program for low-income households and tax credits worth hundreds of dollars for both customers and contractors.

Expecting the market to move more slowly than advocates predicted, the Colorado Energy Office and the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment recommended a 41% cut. But then in September, after reviewing stakeholders’ comments, the agencies dropped it to 31% — a “more realistic, yet still ambitious goal,” they wrote.

The agencies’ 41% proposal was “far better supported” by their own analysis, Commissioner Megan Gilman said at the Nov. 12 commission meeting: Agencies found that this target comports with the clean-heat law. The 31% figure, by contrast, seemed untethered to the legislation’s mandates, she noted.

The commission’s decision doesn’t factor in concerns about the cost of decarbonization — nor is it meant to, Gilman said. The regulators will address cost-effectiveness when they evaluate utilities’ specific plans for complying with the statute, which are required every four years. Xcel Energy, the state’s largest utility, will file its next plan in 2027.

Even as Colorado doubles down to leave gas in the past, Xcel isn’t planning to relinquish the fossil fuel anytime soon.

Xcel provides gas to 1.5 million customers across the state. From 2025 to 2029, the utility is seeking to invest more than $500 million per year on the gas system — costs passed on to customers via their energy bills. That’s a bigger investment than Xcel’s $440 million plan for 2024 to 2028 to reduce reliance on gas by implementing clean-heat measures.

Overbuilding gas infrastructure now could have decades-long ramifications for energy bills. “If utilities are not scaling these [electrification] programs, the customers left on the gas systems are ultimately going to face higher costs,” said Courtney Fieldman, utility program director of the Southwest Energy Efficiency Project.

Colorado is nudging gas utilities to instead become clean-heat utilities; for example, lawmakers have directed the companies to pilot zero-emissions geothermal heating projects and thermal energy networks.

Meanwhile, the commission’s November decision sends a clear signal that utilities need to adjust their gas-demand forecast, the Sierra Club’s Dennison said. While advocates hoped that regulators would create more policy certainty by setting targets beyond 2035, commissioners demurred. They have until 2032 to get those standards finalized.

“The targets that conservation advocates have proposed are achievable,” said Ed Carley, an expert on building decarbonization policy at Western Resource Advocates. Adopting them “is really our opportunity to be a leader in achieving our greenhouse gas emissions goals — and demonstrating that market transformation is possible.”

WESTERN MACEDONIA, Greece — For more than a decade, Lefteris Ioannidis had been saying what no one wanted to hear: Coal is dying, and it’s time to prepare for what comes next.

He could see the writing on the wall while serving as mayor of Kozani, the largest city in Western Macedonia, even as other local politicians wanted to build new power plants and dig more coal from the region’s sprawling mines. The president of the coal workers’ union said Ioannidis was dead wrong.

But coal production had been sagging since the early 2000s. The power plants were getting too costly to run, thanks to new pollution rules. And extracting and burning the fossil fuel — which in Western Macedonia is mined in vast open pits that over the decades have destroyed homes, entire villages, and lives — was clearly incompatible with the European Union’s vision for a green future.

Still, even Ioannidis didn’t believe Greece would abandon coal so soon.

Just over a decade ago, more than half the country’s electricity was produced by burning through mountains of lignite, the lowest-grade form of coal. Now, if all goes according to plan, Greece aims to shutter its last two coal-fired power plants next year and stop producing coal from most of its mines, including one that is among the largest in Europe. In coal’s place, the country is building clean energy — mostly solar — at a feverish pace.

Western Macedonia, a landlocked and sparsely populated region far north of Athens and the iconic whitewashed buildings of the Cyclades islands, is at the center of this rapid transition.

The region sits atop the biggest lignite deposits in Greece. Over the course of six decades, the once state-owned PPC Group pulled hundreds of millions of metric tons of coal from the area’s soil, producing thousands of jobs and eventually most of Greece’s electricity — along with devastating environmental and health consequences.

Today, things are changing. Blue-black lakes of solar panels shimmer across the valley floor, busily converting the bountiful Greek sun into clean energy, while others wait to be plugged into the grid. The installations stretch to the edges of quiet mines and surround idled power plants. Lonely plumes of steam escape from the cooling towers of the few coal units that remain online, wavering in the wind like white flags of surrender.

Soon, PPC will complete the construction of 2.1 gigawatts of solar in Western Macedonia, erected mostly on top of remediated coal lands. It will be the largest cluster of solar panels in Europe. Most of it was built within the last 12 months.

The success of the region’s energy transition is undeniable. But so too is the failure to build an economy for the post-coal era. Even though Greece announced back in 2019 that it would eliminate coal, uncertainty reigns over Western Macedonia’s future, and the region remains wracked by poverty and unemployment.

“We had an economy dominated just from coal, and everybody knew that the coal would have to end,” said Ioannidis. “But nobody did anything to prevent the disaster. It’s like the Titanic — everybody dancing on board, but the disaster is coming.”

Most of PPC Group's massive solar cluster in Western Macedonia was built recently, as is visible when comparing satellite imagery from October 2024 to April 2025.

The situation underscores an urgent question as 17 other European nations work to eliminate coal over the coming years: How can a country do what’s right for the planet without wronging the people who depend on fossil fuels for jobs?

The European Union is searching for answers: In 2021 it created a €17.5 billion fund “to ensure no one is left behind on the road to a greener economy.”

The following year, Greece became the first country to have a just-transition plan approved by this fund. But to date, only a sliver of the nearly €1 billion allocated specifically to Western Macedonia has trickled into the impacted communities. There’s not yet a large-scale flagship project in operation — something to demonstrate what a world without coal might look like.

Ioannidis says the lack of progress is unacceptable, the result of a top-down, Athens-led approach that has left little room for the locals to shape their own destiny.

“The main path is to create a bottom-up strategy,” he said. “But I’m not optimistic. I’m not waiting for anything from the government. For them, Western Macedonia is only a very small part of Greece. … Anything outside Athens, it’s not a priority.”

This sense of fatalism hangs over the region like smog. Frustrated by the lack of progress, many residents are leaving in search of better prospects.

It’s a devastating feedback loop: Every working-age resident who pursues a job in Athens or Thessaloniki, every young person who goes off to university and never returns, is one less person to help wrest Western Macedonia from the quicksand of its dirty past. The task of inventing the future becomes harder with each departure — and the sense that it is possible to do so becomes that much more remote.

On a warm Sunday evening in September, every bench in Plateia Nikis, Kozani’s main plaza, was full.

Conversation rose from the tavernas that line the west side of the plaza. Groups of teenagers roamed the pedestrian-only street that feeds into the plaza from the south, pushing one another around and giggling their way into one of several nearby arcades. A child kicked a soccer ball in the plaza’s center and suddenly 10 more appeared; a game began. Another cut across the match, running not after the ball but to hug her grandmother, whom she had spotted from across the way. An elderly couple sat next to me on a bench, and the man offered me a cigarette. I declined politely in Greek, and together we watched silently as the fading sun painted the Kozani clock tower gold.

Just blocks away, the atmosphere was far less vibrant. As I walked away from Plateia Nikis, the bustling shops and cafés gave way to empty storefronts, their smudged windows covered in white paper signs with big red letters that read “ΕΝΟΙΚΙΑΖΕΤΑΙ” — “for rent.”

Outside a bar on one of these side streets, I met up with Sokratis Moutidis, the longtime editor-in-chief of Chronos Kozanis, Western Macedonia’s oldest newspaper. He and two other residents who sat with us explained that these quiet streets were once home to nice shops.

The contrast illustrates how Western Macedonia is struggling to adapt to the end of coal, its core industry for over half a century.

Then entirely state-owned and known as the Public Power Corporation, PPC opened its first major lignite power plant in 1959, perched on the edge of a coalfield located about 15 miles north of Kozani. Its smokestack jutted from the valley floor, a symbol of Greece’s rapid modernization; it was the tallest structure in the nation upon completion.

In the decades that followed, PPC built a total of 15 coal-fired units across the region, which provided over 70% of Greece’s electricity at its high-water mark. (The newest one, Ptolemaida 5, was brought online in 2023 — four years after the country decided to eliminate coal — at a cost of nearly €2 billion. PPC will convert it to gas by 2028.) Western Macedonia’s mines swelled in step with its coal fleet, and by the early 2000s Greece was the world’s fourth-largest producer of lignite.

Coal created not just jobs for miners and engineers but also a bustling secondary economy of mechanics, truck drivers, and lunch-spot proprietors. As much as 20% of the working population was employed directly or indirectly by the sector, according to a 2020 World Bank study. Lignite generated a whopping 42% of Western Macedonia’s gross domestic product.

But as soon as world leaders signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, awakening at last to the reality of climate change, the clock started ticking, Ioannidis said. It became inevitable that someday time would run out for coal — in Western Macedonia and beyond.

The only question was when.

As mayor of Kozani from 2014 to 2019, Ioannidis was not content to wait around for an answer. In 2016, he organized the city’s first public discussion about life after lignite. He also convinced the World Bank to visit the region in order to create a road map for how it could move beyond coal.

But by the time the World Bank recommendations came out in 2020, the post-lignite era was already hurtling toward Western Macedonia. The year before, just months into his first term, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis had stood before the United Nations Climate Action Summit and pronounced that Greece would “close all lignite power plants, the latest by 2028,” an inspired target for a country in which the industry was so deeply entrenched. That timeline has since been accelerated to 2026.

“We lost many decades to understand the problem, to realize the problem,” said Ioannidis. “Now we don’t have time.”

Though Mitsotakis’ announcement was couched in soaring rhetoric about the imperative to deal with climate change, it was ultimately long-simmering regulatory and economic forces that brought lignite to its knees.

In 2005, the EU launched the Emissions Trading System, a cap-and-trade program that puts a price on carbon dioxide emissions. The scheme hit lignite especially hard because it emits more than other forms of coal do. Five years later, the EU clamped down on air pollution from industrial sources. Meanwhile, the cost of natural gas, wind, and solar power began to plummet. These trends converged, and as the region’s carbon price slowly crept up, the profitability of PPC’s lignite plants went down.

Still, the phaseout came as a surprise.

“In Greek, when we want to say we are in shock, we say ‘Our legs were cut,’” said Ioannis Fasidis, a 44-year-old coal miner and power plant worker who is now president of Spartakos, a major union of PPC workers, via Moutidis, who translated. “It was a shock.”

That shock is still reverberating throughout Western Macedonia.

No region in Greece, itself a shrinking nation, is losing people faster. Between 2011 and 2021, the year of the most recent census, Western Macedonia lost 10.3% of its population. It has one of the highest youth unemployment rates in Europe: In 2023, more than one-third of young people there were out of work, compared with nearly 22% nationwide and 11% across the EU.

The future of Western Macedonia, it feels, is slipping away — even as the region drives the increasingly ambitious Greek energy transition forward.

In April, Mitsotakis and PPC Chairman and CEO Georgios Stassis stood outside the decommissioned Kardia power plant and unveiled a €5.75 billion “green” vision for Western Macedonia.

Some of that plan is already underway — namely PPC’s colossal solar installations and the company’s work restoring already inactive mine lands. But it also included more aspirational proposals, like turning two lignite mines into pumped hydroelectric facilities and converting Ptolemaida 5 to a hydrogen-ready gas-burning facility. In total, PPC says the plan could create up to 20,000 construction jobs and 2,000 permanent jobs.

“If we wanted to be very fast in phasing out coal and developing renewable energy — and mostly solar — we had to leverage all of the weapons in our armory. There, we owned the land, we had space. We owned the grid connections,” explained Elena Giannakopolou, the chief strategy officer of PPC. “That’s why Western Macedonia was such a special place for us. It was our vehicle to the new day.”

I could see that new day dawning when I visited PPC’s expansive Western Macedonia facilities in September.

Immediately outside the silent turbine hall of the former Kardia power plant, whose four units were shut down between 2019 and 2021, electric boilers now sit to help heat Kozani’s buildings during the city’s chilly winters — a job previously done by the lignite plants. Across the street, construction was newly underway on a gas-fired thermal plant that will also help with heating. Five minutes up the road, PPC’s first-ever grid battery facility was being built. The red-and-white cooling tower of Ptolemaida 5 stood in the distance.

A short drive away was the Kardia mine, which once fed piles of lignite to the units of the power plant that shares its name. From within the mine, some PPC engineers explained how the great crater will gradually fill with rain and groundwater and be repurposed as a pumped-hydro station, an old-school form of energy storage that harnesses gravity to squirrel away electricity. Already, a deep blue pond sat on the mine floor as if to suggest the future.

Past the Kardia complex, fields of solar panels stretched so far that when I looked out from among them, I could see only the region’s most striking features in the distance: the occasional coal excavator rising like a skyscraper; the towers of the half-dead, half-alive Agios Dimitrios coal-fired plant; and the mountain peaks that ensconce the Ptolemaida basin, the physical delimiters of a region whose fate was determined by geological machinations long ago.

PPC’s rapid transformation from a lignite giant to a “powertech” firm that develops clean energy and gas is a microcosm of Greece’s energy transition more broadly.

Earlier this year, the country increased its renewable energy targets under its EU-mandated National Energy and Climate Plan. Previously, Greece aimed to get 66% of its electricity from renewables by 2030 — a figure it flirted with this spring. Now it’s targeting 76%, and the virtual elimination of fossil fuels from its grid by 2035. (PPC, meanwhile, says it will see its emissions plummet by a staggering 85% between 2019 and 2028.) Mitsotakis, whose country was once singled out as a laggard on clean energy, is now taking to the Financial Times’ op-ed pages to lecture other nations on “golden rules” for the green transition.

Made with Flourish • Create a chart

For all the progress on renewables, however, fossil fuels are not yet in the country’s past.

Natural gas, that pesky “bridge fuel,” is on the rise in Greece. Once a comparatively small part of the Greek grid, it provided nearly 40% of the country’s power across 2024. The nation has opened major import infrastructure for liquefied natural gas, positioning itself as a hub for Europe, and is proudly courting Chevron and Exxon Mobil to explore for the fossil fuel off the coast of Crete.

Some influential groups are also pushing to keep burning coal.

One prominent example is the coal workers’ union led by Fasidis. We met at a shady café on a hot afternoon in Kozani, and Moutidis, the local journalist, translated. A serious but not unfriendly man, Fasidis brought his two preteen daughters along, who chimed in occasionally when Moutidis was stuck searching for a word.

Fasidis is in active negotiations with PPC about the future of his roughly 1,800 mine and power plant workers. Though he welcomes the company’s new investment plan, he was clear on what the union really wants.

“Our main goal is for lignite, coal, to be alive,” he said. “This is the main demand of the union.”

He clarified that it is “not an economical point of view” but rather one based on energy security concerns. Greece imports all the natural gas it consumes; lignite remains its core domestic fossil fuel. This fact offered Fasidis and his workers a brief reprieve three years ago, after Russia invaded Ukraine and spurred the worst European energy crisis since the 1970s oil shock that pushed Greece to embrace lignite to begin with.

“But it’s not realistic today to talk about lignite,” said Ioannidis, who later pulled up a chair and joined the conversation with Fasidis — a man he had clashed with as the mayor soothsaying the end of coal.

“Lignite is a dead man,” Ioannidis concluded.

That reality was hard to forget even when I stopped by the Agios Dimitrios power plant during my tour of PPC’s energy complex.

In the hulking facility’s coal yard, I was surrounded by screeching conveyor belts carrying lignite, and my eyes watered and nostrils stung from the caustic swirls of coal dust. But I could also see some telling graffiti spray-painted on one of the power plant’s cooling towers. A decade ago, activists had climbed the steel structure and left behind a message: “GO SOLAR” — a message that now, with all the challenges it brings, the region is heeding.

But for all the clean energy being built in Western Macedonia, the boom is creating little wealth for the people who live there.

Konstantinos Siampanopoulos, a 34-year-old resident of Kozani, is a case in point.

Siampanopoulos is a restless entrepreneur. Details of venture after venture dribbled out as we spoke over meze at a Kozani taverna. There’s the fur clothing brand he founded, the accounting firm he runs, and, most recently, a facility where locals can play the squash-like racquet sport padel.

Siampanopoulos is also a longtime investor in renewable energy, one of the few locals who managed to get in early on the region’s solar boom. In 2010, he and his father developed their first solar installations. In partnership with other investors, their portfolio grew to 16 megawatts, including some small hydropower projects. But as the country has become awash in solar, he told me, what was once a prescient and profitable bet has soured.

Holding up a phone displaying the real-time market dashboard from Greece’s grid operator, he showed me the problem for small investors. “Tomorrow, the price is zero. It’s zero for many hours,” he said. “We signed the contract that if the price is zero for more than two hours, we are not paid.”

Put simply: Greece often has more solar power than it can use. Plans to build energy storage will help alleviate this problem, but that’s small comfort for investors like Siampanopoulos right now. Under the current conditions, he and his coinvestors were hardly able to keep up with the loan payments on their installations, let alone earn an attractive profit. They sold 10.8 MW of their portfolio in August.

These price dynamics, among other challenges, have made it difficult for locals to profit from the energy transition.

Overall, at least 95% of the operational or licensed renewable projects in Western Macedonia are owned by large investors, per April 2024 data from Greece’s transmission and distribution grid operators shared by Siampanopoulos; he obtained and analyzed the data in his capacity as a member of the Kozani Chamber of Commerce and president of the local photovoltaic investors’ group. That means only a fraction of the wealth is going directly to residents.

“I characterize this as an air bridge, by which income is transferred from Western Macedonia to somewhere else,” said Lefteris Topaloglou, a professor who runs the Energy Transition and Developmental Transformation Laboratory at the University of Western Macedonia.

In one sense, this is nothing new. Although majority owned by Greece until 2021, PPC was still a single large entity — headquartered elsewhere, in Athens — that controlled the energy infrastructure in Western Macedonia.

But the coal-fired power plants made up for this centralized ownership with jobs. Solar provides neither significant revenue nor employment to residents. PPC declined to disclose the exact number of permanent jobs that its solar installations have created in Western Macedonia to date.

In some ways, this is a good thing. Solar results in so few jobs once installed because it requires no fuel and little maintenance. That’s one reason it is the cheapest form of energy, and that affordability is itself why solar is growing at blazing speed worldwide — giving humanity a chance to kick our self-destructive habit of burning fossil fuels like lignite.

Coal, by contrast, creates jobs because it is extractive. Humans must pilot excavators that disfigure the Earth to produce coal, which then must be transported by humans to power plants, where yet more humans oversee operations. Its economic benefits are a direct function of its pollution, of its destruction; its jobs are paid for with the health of workers and nearby residents and that of the planet.

But the point remains for the people of Western Macedonia: Solar isn’t bringing them jobs.

“This is the employment paradox of the green energy boom,” said Topaloglou.

On a brisk and sunny morning in early October, the marble sidewalks of Athens slick from the previous day’s uncharacteristic downpour, I met Alexandra Mavrogonatou in her office near the Hellenic Parliament.

She offered me an espresso, a comfortable seat, and a history lesson. In June 2022, she explained, Greece became the first country to receive European Commission approval for its €1.63 billion just-transition plan. Most of the money comes from the EU’s broader Just Transition Fund, which supports 96 regions across the bloc.

Mavrogonatou is the head of the directorate of strategic planning and coordination of funds for Greece’s Just Transition Special Authority. That means she oversees the implementation of the country’s just-transition program, from which Western Macedonia was allocated about €994 million. The rest is split between the country’s other main lignite area, Megalopolis, and then among the islands and other mainland regions.

To date, her agency has made some progress: It has approved projects amounting to 50% of the funds and inked contracts with awardees for almost 35% of the funds, she said. But through September, she told me, less than 5% of the money had actually been given to the beneficiaries.

“This percentage may seem low, but we need to take into consideration that we are a newly established program,” Mavrogonatou said. “We’ve had no projects coming from a previous programming period, so we started from scratch — from zero.”

Most of the funding approved by Mavrogonatou’s office so far is for projects in Western Macedonia, she said.

Entrepreneurship has been a main focus, and the office to date has greenlit more than 500 such investments for the region, she said. It funded the creation of a coworking space and a startup incubator in Kozani. The 22-person accounting firm Siampanopoulos manages received approval for funding, and he’s working on securing money for his padel hub, too. The agency has also funded regional support offices in Kozani and the city of Florina — “one-stop shops” for entrepreneurs, she said — as well as a skills development and employment center in Kozani.

But during my five days in Western Macedonia, locals dismissed these sorts of programs as not enough. They are not unwelcome, necessarily, but viewed as insufficient. Ioannidis called them “very, very soft actions.”

“We are full of soft actions and programs,” he told me, weeks before my conversation with Mavrogonatou, while on a break from his job managing a 40-person health clinic in town. As we spoke at his favorite café, the former mayor fielded a steady stream of greetings. Some passersby pulled up a chair, Ioannidis poured them a glass of beer, and they sat and chatted before continuing on their way.

“That’s enough with soft actions, trips, discussions, studies,” he said. “We need jobs. We need something concrete.”

Ioannidis’ frustration is shared by many in the region: Even though it’s been six years since Mitsotakis’ fateful announcement, there’s been no large-scale job creation, and there’s not a clear and broadly understood vision for how to change that.

Above all, the residents I spoke to feel that they’ve had no chance to participate in planning for what comes next.

When I brought up these criticisms to Mavrogonatou in Athens, she said she “totally” disagrees with the notion that locals have had no voice. She pointed to working groups in Western Macedonia, which are staffed by representatives from the local university and municipalities and which are under the supervision of the region’s governor. The idea, she said, is to provide a way for one unified stream of feedback to flow to Athens.

Be that as it may, the perception that the transition is being mismanaged is real — and that perception is eroding trust in the entire process. Ongoing field research from Fenia Pliatsika, a doctoral student in Topaloglou’s lab, found a high level of concern that the transition is suffering because of a lack of trust and “tokenistic participation,” echoing similar peer-reviewed findings published by Topaloglou and Ioannidis in 2022.

Perceived inconsistencies in the government’s stance on clean energy threaten to wash away what little confidence remains.

Again and again, throughout my time in Western Macedonia, residents called out two projects as confusing and unfair.

First, there’s the waste-to-energy facility. Under an EU regulation, Greece needs to rapidly decrease the amount of trash it puts into landfills. Its proposed solution is to construct six incinerators around the country that will burn garbage for energy. That includes a facility PPC intends to build at the site of Ptolemaida 5, to which waste would be trucked in from as far as the island of Corfu. Opposition runs deep. Fasidis singled it out as the only proposed new investment the union is against. As I returned from touring PPC’s energy complex, a protest against the plant was winding down, the shouts of opposition still ringing through Kozani’s narrow streets.

Then, there is the lignite mine in the village of Achlada, near Florina. The facility, which is not owned by PPC, ships its coal across the border to North Macedonia, home to one of the most polluting power plants in Europe. The mine has a contract in place until 2028.

Locals make the point that the government is all but eliminating the industry that has anchored their economy for decades in the name of a green energy transition while embarking on two projects that undermine that very effort. In their view, the government is still allowing dirty activities — but only the ones it finds convenient.

Back in Athens, Mavrogonatou urged patience. She stressed that her agency has had only a few years to achieve something difficult — the wholesale transformation of a regional economy — and that results will take time. The projects approved so far will create 2,500 permanent jobs in Western Macedonia, she said. Her team has until 2030 to spend the money.

“We’re trying to do the best we can for the area,” she said. “We’re not perfect. No one is perfect in this world, but I am pretty sure that very soon, especially during 2026, the area will start seeing the first results of our effort.”

The microchip factory her office approved for funding in 2024 is one example. Greek telecoms firm Intracom plans to break ground soon on a €45 million facility and complete construction by 2027. It will create at least 150 skilled jobs.

She also pointed to her agency’s plan to build an “innovation zone” at the University of Western Macedonia’s main campus. It’s a sweeping idea that includes everything from a green hydrogen hub to a supercomputer, as well as mechanisms for university researchers to commercialize their work via startups. Funding for the project has been approved, but construction has not yet begun.

The projects are all part of the nebulous plan to turn the energy-rich region into something of a tech hub for Greece.

Perhaps the most promising venture on this front is one that Mavrogonatou’s office has nothing to do with: a huge data center proposed by PPC as part of its April investment plan.

The €2.3 billion, 300-megawatt facility would replace the lignite field outside the Agios Dimitrios plant. PPC says it can have the data center online by 2027, a potentially appealing timeline for tech firms that are struggling to swiftly secure energy to power their artificial intelligence strategies.

“Time to market is one of the most critical, if not the most critical, points in this decision,” said Giannakopolou of PPC. “Building the building is not difficult. What’s difficult is to have grid connections, to have electricity to power the data center.”

If the demand is there, PPC says it can scale the facility to 1,000 megawatts — a move that would make it among the largest data centers in Europe and also spur the company to outfit Ptolemaida 5 with a 500 MW combined-cycle gas turbine. The facility would, in theory, help propel the area’s startup ecosystem by attracting young, tech-savvy professionals. PPC declined to disclose exactly how many jobs the data center or its related gas-turbine upgrades would generate.

But these visions of a high-tech economy are tentative at best. PPC has to convince a major tech company to set up a data center in Western Macedonia — and that’s just the first step. PPC said that negotiations are active but declined to provide further detail.

Marquee projects promised to the region have fallen apart before. A €1.4 billion lithium-ion battery manufacturing facility was supposed to bring more than 2,000 permanent jobs; it was abandoned late last year. An €8 billion green-hydrogen complex that pledged an audacious 18,000 direct jobs fizzled out after failing to secure European Commission funding.

Amid these false starts, the pleas for patience from Athens have worn thin. As the journalist Moutidis put it in a message after I spoke with Mavrogonatou, “Since 2019, they’ve been saying, ‘Next year things will be better — just be patient.’”

The hope, of course, is that the cynicism is wrong. That the big ideas do work out — that, very specifically, the data center gets built. The residents I spoke to want the region to see a large-scale project that isn’t coal, not only for the much-needed jobs it will bring but also for the symbolic weight — for the suggestion that it’s possible for Western Macedonia to reinvent itself.

“The first buildings, the beginning of the construction — it will be a good signal,” said Ioannidis. “We need a good signal here. We need a flagship investment. This is the main problem: The people here don’t see a good signal and lose their belief in this process.”

“This is not political,” he clarified, before pausing, searching for the word in English. “It’s psychological.”

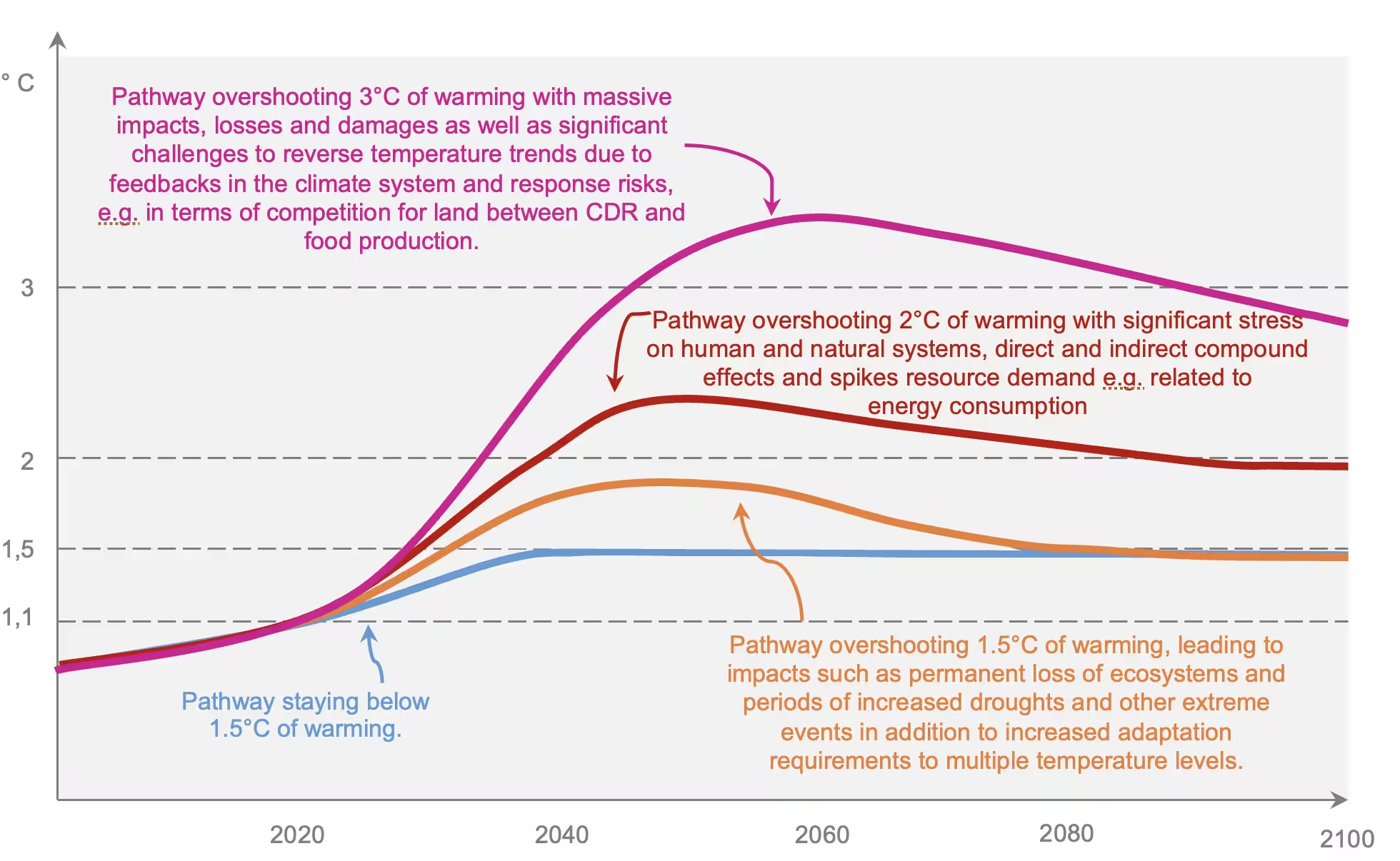

Climate change impacts of relevance for the humanitarian sector and beyond include (a) the timing of temperature exceedance, (b) the peak warming and (c) the duration of overshoot.

As global temperatures appear likely to surpass the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 °C target by 2050—and remain above it for decades—researchers warn that governments and aid organizations aren’t prepared for what this “climate overshoot” will mean for people and societies.

A perspective published today in PNAS Nexus suggests that while scientists have made progress describing overshoot’s physical impacts, its humanitarian and social consequences need greater focus. The authors call for urgent action to build the evidence, data and policy links needed to plan for decades of heightened, uneven climate risk before that window closes.

“Climate overshoot is no longer a distant possibility,” said lead author Andrew Kruczkiewicz, senior researcher at the Columbia Climate School’s National Center for Disaster Preparedness.

“Understanding how overshoot will affect people’s lives and livelihoods—before, during and after disasters—must be part of climate planning, policy and finance. To do otherwise is increasingly irresponsible, with the cost of doing nothing potentially creating tensions with the humanitarian principle of ‘do no harm.’”

The authors outline five interconnected factors linking Earth’s physical changes to social and humanitarian consequences.

Peak warming and duration. Even a short period of overshoot could lock in sea-level rise and other irreversible effects, while higher or longer warming peaks would magnify losses and strain the financial reserves that underpin recovery. Because systems like groundwater and ice sheets respond slowly to heat, some impacts could persist for centuries, even after temperatures stabilize.

Geography will shape who faces the greatest risks. The world won’t feel overshoot evenly: Regions warming faster than the global average are home to some of the world’s most socially and economically vulnerable populations. Limited capacity to prepare or recover means these communities may experience compounding crises, shifting where humanitarian needs are most acute and deepening inequities.

The timing of overshoot’s arrival. The rate of warming will determine whether systems can adapt in time. Rapid warming can outpace infrastructure and ecosystem adjustments, while slower change could allow for limited adaptation.

Adaptation limits and vulnerabilities. Overshoot could push some communities beyond the limits of feasible adaptation, creating cascading risks across food, water, health and energy systems. Implementing short-term fixes can lead to maladaptation, or solutions that solve one problem while creating others.

The path back down may bring new risks. Returning temperatures below 1.5 °C will require large-scale carbon dioxide removal, which could compete with agriculture, fisheries and livelihoods if these technologies repurpose land or ocean resources. Recovery paths with cycles of warming and cooling would also complicate disaster financing and planning. Policy discussions often fail to represent these variable recovery pathways, even though they would create different operational demands on the humanitarian sector.

To avoid widespread system strain, the authors stress the need for stronger links among climate science, social data and humanitarian operations. They recommend expanding research on the social and economic dimensions of overshoot, improving data from vulnerable areas and strengthening scenario planning that anticipates irreversible change and immediate threats.

“In a period of overshoot, the course our social and climate systems take will depend on how we respond to new and unpredictable shocks,” said coauthor Joshua Fisher, a Columbia University research scientist and director of the Columbia Climate School’s Advanced Consortium on Cooperation, Conflict, and Complexity.

“Because those shocks are difficult to predict, institutions will need stronger coordination and collaboration to stay flexible and respond effectively.”

Governments can reduce the risks associated with overshoot by accelerating emissions cuts to limit its magnitude and by investing in adaptation and early-warning systems that help communities cope with prolonged heat, food security pressures and other impacts. Without such foresight, countries could underestimate humanitarian needs or put resources toward responses that no longer fit future conditions.

Overshoot will also challenge how societies think about time and preparedness. Infrastructure designed for one hazard may prove inadequate for another, and the regions most at risk now may not be the same in the future. For example, a city that’s fortified its coast against storm surge could later face other types of flooding if rainfall patterns shift, demonstrating why adaptation approaches must evolve as conditions change.

Even if global efforts succeed in bringing temperatures below 1.5 °C, recovering from overshoot won’t be straightforward. How temperatures drop will matter as much as how high they rise—gradual cooling could ease adaptation pressures, but erratic cycles of warming and cooling could increase instability. Addressing this variability requires flexible approaches to risk reduction, disaster response, and infrastructure investment and closer coordination between climate and humanitarian planning.

The authors emphasize that meeting the Paris Agreement target is essential, yet warn we must also prepare for the possibility of temporarily exceeding it. Planning for the distinct phases of overshoot is not about accepting failure, but about anticipating change and protecting those most at risk.

The article’s coauthors are Zinta Zommers, Perry World House, University of Pennsylvania; Joyce Kimutai, Kenya Meteorological Service and Imperial College London; and Matthias Garschagen, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München.

Around the world, smelters use massive amounts of electricity — often generated by fossil fuels — to turn raw materials into aluminum. As more carbon-free energy comes onto the grid, these power-hungry facilities will get progressively cleaner. But smelters will never be entirely emissions-free until producers can solve a much trickier technical problem.

That’s because modern aluminum plants rely on a 19th-century process that uses big blocks of carbon, which account for almost one-sixth of the greenhouse gases associated with producing new aluminum globally. Replacing the blocks is crucial to decarbonizing this key industrial process.

Now the industry may be one step closer to reaching that goal.

Earlier this month, the Canadian firm Elysis said it hit a major milestone when it deployed an industrial-size, carbon-free anode inside an existing smelter in Alma, Quebec. Elysis is a joint venture of the U.S. aluminum giant Alcoa and global mining company Rio Tinto, both of which produce aluminum in the Canadian province.

“This is really a first for the aluminum industry, and a worldwide first as well,” François Perras, president and CEO of Elysis, told Canary Media.

Elysis installed its “inert,” or chemically inactive, anode technology in a 450-kiloampere (kA) cell, the same amount of electric current used in many large, modern smelters. The full-scale prototype is a significant step up from the company’s 100 kA pilot unit, which has produced low-carbon aluminum used in certain Apple laptops and iPhones, Michelob Ultra beer cans, and the wheels for Audi’s electric sports car.

Elysis launched in 2018 and has raised over 650 million Canadian dollars ($460 million) in investment for the effort, including from the governments of Canada and Quebec. The 450 kA cell will undergo several more years of testing as the company works to measure and validate how the larger unit performs inside a commercial smelter.

Rio Tinto, meanwhile, has already licensed the inert-anode technology from Elysis. The manufacturer plans to build a demonstration plant with 10 of the 100 kA cells at its existing Arvida smelter in Quebec, possibly by 2027, through a joint venture with the provincial government.

“We’re trying to replace a process that has been used for close to 140 years,” Perras said of the initiatives.

Elysis belongs to a small but persistent group spread across China, Iceland, Norway, and Russia that aims to disrupt the smelting method known as the Hall–Héroult process.

Smelting involves dissolving powdery alumina in a molten salt, which is heated to over 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit. Large carbon anodes are lowered into the highly corrosive bath, and electrical currents run through the entire structure. Aluminum then deposits at the bottom as oxygen combines with carbon in the blocks, creating CO2 as a by-product. It also releases perfluorochemicals (PFCs) — long-lasting greenhouse gases — as well as harmful sulfur dioxide pollution.

The anodes themselves are made using petroleum coke, a rocklike by-product of oil refining.

The Hall–Héroult process was revolutionary, but it is extremely energy-intensive. Most of the emissions associated with producing aluminum are tied to electricity production. In the United States, more than 70% of CO2 pollution from six operating smelters came from the power supply in 2021, according to the Environmental Integrity Project. (The U.S. now has four smelters left, three of which rely on fossil-fuel power.)

Another 20% of U.S. smelters’ carbon emissions were directly from the electrochemical process, the EIP study found. Smelting was also responsible for virtually all the PFCs reported by metal producers to the Environmental Protection Agency that year.

The solution to reducing electricity-related emissions is relatively straightforward: Deploy vast amounts of wind, solar, battery storage, and other clean energy sources. But completely eliminating emissions from the smelting process requires redesigning how the anodes and cells work — and researchers are only just beginning to develop commercial-size alternatives.

Smelting represents “the hardest-to-abate emissions from primary aluminum production,” said Caroline Kim, a technical analyst on climate and energy at the Natural Resources Defense Council. “It’s really important that we’re able to replace carbon anodes,” she added, noting that PFCs last for tens of thousands of years longer in the atmosphere than CO2 does.

Elysis and other inert-anode developers have been tight-lipped about the composition and performance of their technologies, often citing trade secrets. But Elysis’ industrial-scale prototype, as well as Rio Tinto’s future demonstration plant in Quebec, could provide key answers about whether inert anodes can become the game-changing solution that many aluminum and climate experts are betting on.

“Now that it seems like [Elysis’] technology can work, the question is more about, can it be done at full-scale, sustained operating conditions at or below current costs?” Kim said.

Perras didn’t say what kinds of materials Elysis uses in its anodes. “This is our secret sauce,” he explained. But generally, the idea is to use inert metallic alloys or ceramics that don’t contain carbon, and thus won’t release CO2 and PFCs when zapped with electricity.

Elysis has also swapped the horizontal design of typical smelting pots for a “vertical approach” that Perras said looks more like a battery. These and other technical changes are expected to increase the lifespan of anodes by several years, so aluminum producers won’t have to replace them as often as they do carbon blocks, ideally reducing costs.