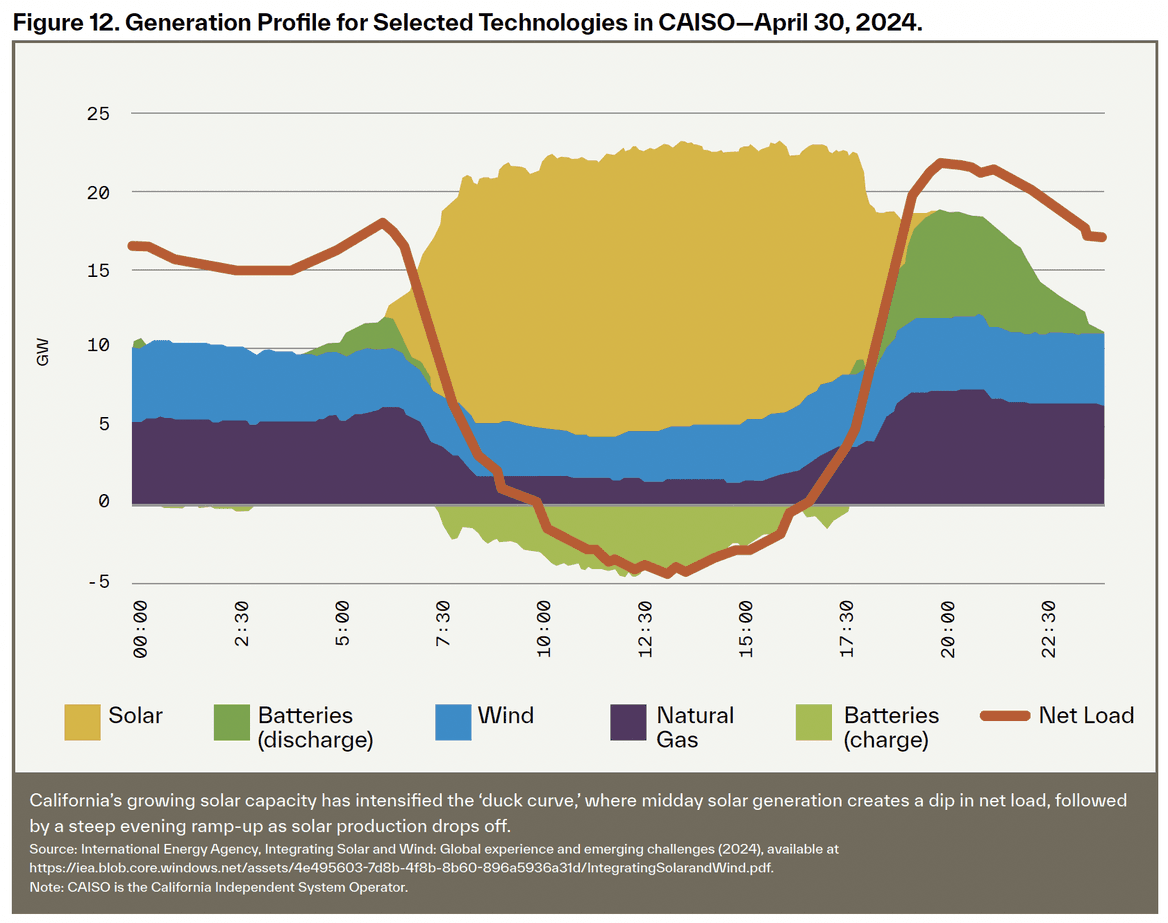

California’s power system has an infamous problem. Solar projects produce more electricity than is needed during the day but too little to satisfy demand at night. So the state’s major utilities are developing new electricity rates to encourage their largest customers to shift to using more power during those hours of sunny abundance.

The undertaking is meant to cut utility bills and curb carbon emissions across the grid. But climate advocates say it also could be a crucial tool for tackling another energy challenge in the state: industrial electrification.

Some 36,000 manufacturing facilities operate in California, and many use large amounts of fossil gas to produce everything from cheese, olive oil, and canned fruit to cardboard, medicines, and plastic resins. Switching to electrified processes would significantly and immediately slash emissions from those factories, experts say. Yet industrial firms are generally hesitant to change — and sky-high power bills are a major reason why.

“It’s been a huge barrier to electrification for manufacturers,” said Teresa Cheng, California director at the decarbonization-advocacy group Industrious Labs.

Industrial customers in California pay over 19 cents per kilowatt-hour for electricity, which is more than twice the national average. They also pay demand charges based on their peak power usage during the month. These costs can represent around 30% or more of a facility’s utility bill — effectively penalizing companies for increasing their electricity use, Cheng said. Meanwhile, industries still pay relatively less for fossil gas.

This dynamic threatens to undermine the state’s broader efforts to get factories off fossil fuels, she added. California’s industrial sector uses one-quarter of all the fossil gas burned in the Golden State, and it contributes over 20% of the state’s annual greenhouse gas emissions, along with health-harming pollution.

In recent years, state lawmakers and regional regulators have adopted policies to push manufacturers to electrify their equipment. Last October, Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom signed a law, Assembly Bill 1280, that expands incentive programs to help manufacturers install industrial heat pumps, thermal storage systems, and other clean technologies. In Southern California, the air-quality district in 2024 passed a landmark rule that’s expected to drive adoption of electric boilers and water heaters in the smog-choked region.

“There’s a very strong climate policy from the top down that recognizes that industrial decarbonization is a big part of California’s success,” said Anna Johnson, state policy manager at the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy.

Still, “there hasn’t yet been a really concerted effort to address the operating costs,” she added. “We want to see a clear path for manufacturers both to replace outdated equipment with more efficient, cleaner, and safer equipment, and then also for them to be able to operate economically afterwards.”

Just this week, though, California state Sen. Josh Becker introduced a bill that aims to tackle that missing piece. Senate Bill 943 proposes making changes to electricity rates to help manufacturers and large commercial companies switch to electricity for industrial heat.

Both Johnson and Cheng contributed to a recent report by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, Industrious Labs, the Sierra Club, and Synapse Energy Economies that outlines strategies for updating industrial rates to accelerate electrification.

Their analysis is meant to inform California’s three biggest utilities as they devise new rate options for large customers. The concepts, however, could apply to other parts of the country that have plenty of intermittent renewables, like Texas and the Midwest “wind belt,” and regions where industrial electricity is far more expensive than fossil gas, such as the Upper Midwest and Northeast, Johnson said.

California is facing both realities.

Last August, the California Public Utilities Commission instructed Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric to design dynamic hourly rates that “align electricity prices more closely with grid conditions to promote efficient energy use.” Simply put, the goal is to make it cheaper for large customers to use power when the grid is overloaded with utility-scale solar, which often gets curtailed.

The three investor-owned utilities are required to start offering customers the option of dynamic pricing by 2027, providing a chance to transform how major electricity users pay for power.

One option is to develop granular, real-time rates that allow customers to respond to hourly price signals, which reflect the fluctuations in wholesale market prices or transmission and distribution costs. It would reward companies that, for instance, install thermal energy storage systems to bank electricity when supplies are ample and cheap, then tap the thermal battery when grid power is more expensive or constrained.

Another approach is critical peak pricing, which charges higher electricity rates during a narrow window of peak demand — but also offers lower rates or gives credits to customers that reduce electricity consumption during grid emergencies, helping prevent blackouts. While companies can’t randomly flip their factories off and on, they typically can shift their production times or scale back for a limited period.

Utilities could also eliminate the “non-coincident demand charges” that industrial customers currently pay. As an example, Cheng said, a tomato-canning facility that uses a maximum of 500 kilowatt-hours during the month is charged the same amount whether the plant reaches that peak at 12:30 p.m. in March — a sunny time of day during a mild time of year, when there’s likely a surplus of power — or at 5:30 p.m. during a heat wave, when the grid is overtaxed.

“The way it’s structured is backwards, because it actually punishes electrification and doesn’t reflect the actual cost causation or grid impact of that energy use,” she said.

Encouraging factories to use more off-peak and renewable power should benefit not only manufacturers but also the grid at large, since it reduces the need for utilities to make expensive infrastructure upgrades or add power capacity — costs that all ratepayers shoulder, said Rose Monahan, a staff attorney with the Sierra Club Environmental Law Program, who also contributed to the report.

“Bringing on more electric load and strategically doing that in a way that doesn’t put a huge strain on the grid, and helps use the resources that we already have, should be a win-win for everybody,” she said.

Solving the formidable challenge of electrifying large, energy-intensive operations will require far more than redesigning utility rates — in California and nationwide. Installing new equipment can incur high up-front costs, and fossil gas remains enticingly inexpensive in many regions. Some of the more promising innovations for high-heat industrial processes, like thermal batteries and heat-pump boilers, are only just now hitting the market, meaning companies may be unaware or uncertain of how the cleaner equipment works.

“The [utility] rates on their own won’t do it, and the technologies on their own won’t do it — it’s the combination,” Johnson said. “Being able to have the two of those together in the same place is where you really start to get that market transformation toward these more efficient electric technologies.”