Federal regulators are demanding that PJM Interconnection, the country’s biggest power market, find a faster way to connect data centers to the grid without spiking energy costs or threatening reliability.

Those regulators and other energy experts increasingly believe that a practice known as flexible interconnection is key to juggling those imperatives — and a recent study offers compelling supporting evidence.

Flexible interconnection is simple in principle: Power-hungry customers like data centers supply their own power during the handful of hours per year when overstressed grids can’t handle their needs, allowing them to get online much faster and also save money for customers at large.

But to date, only a handful of utilities and grid operators have developed the technical and regulatory structures to make flexible interconnection a reality.

Astrid Atkinson, CEO of Camus Energy, and Carlo Brancucci, CEO of Encoord, whose companies aim to enable flexible interconnection, say that PJM could deploy the practice on a large scale. That argument is backed by a unique analysis of real-world conditions — modeled across every hour of the year on the same transmission grids that PJM manages — conducted by Camus, Encoord, and Princeton University’s ZERO Lab.

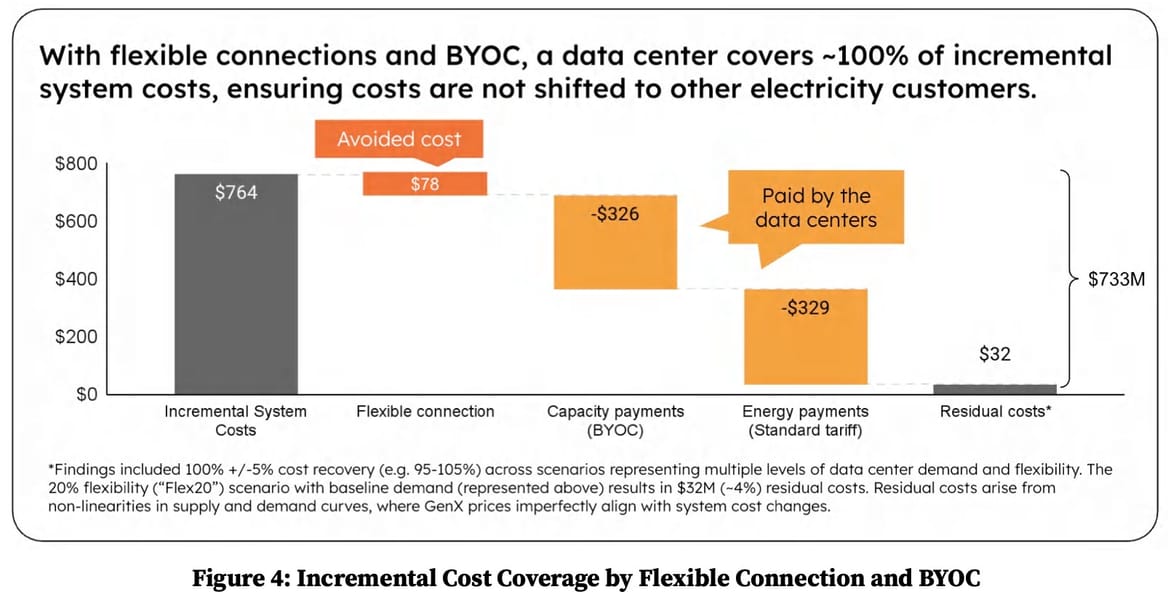

Their December report looks at six sites in mid-Atlantic states served by PJM. It concludes that a 500-megawatt data center using flexible interconnection and providing its own power during times of peak demand could connect three to five years faster than one that has to wait for grid upgrades and new power plants to be built in order to support its full power needs. By paying for the resources to cover any peak demand deficits, these flexible data centers would avoid passing those grid and generation costs on to customers already struggling with rising energy bills tied to data center growth, the report contends.

What’s more, the methods used in the report can be used by grid operators and utilities in PJM and across the country to enable other real-world flexible interconnection studies using standard interconnection tools and datasets, Brancucci said. “Everything else flows from that — what type of interconnection you need, what type of flexibility you need, what kind of contracts and agreements you need.”

“Our companies both offer commercial products that can do this,” said Atkinson, who co-founded Camus in 2019 after leading the team that maintains reliable computing for Google, the report’s sponsor and the preeminent tech giant working on real-world flexible interconnection projects today. In fact, she said, “we’re doing commercial modeling of similar sites right now.”

Data center flexibility is a hot topic. Recent reports from Duke University, think tank RMI, and analytics firms GridLab and Telos Energy all explore its viability and benefits.

But the report from Camus, Encoord, and ZERO Lab differs in a few ways that make it a far more practical blueprint for flexible interconnection, Atkinson said.

The first thing that distinguishes their report is that it uses in-depth, real-world data.

To approve flexible interconnections, utilities, grid operators, and data center developers must have data on power flows from generators across high-voltage transmission grid networks to giant power users. “You do need privileged data access to do this,” Atkinson said — and other research teams haven’t had that access.

But Camus, which provides grid orchestration software for utilities across the United States, including Pennsylvania’s PPL Electric Utilities and Duquesne Light Co., has that data for the six sites it modeled, Atkinson said. She wouldn’t reveal which utilities provided the data or the location of the sites, which in the report were given animal names such as Koala, Pony, Shark, and Whale. But she did confirm that they represent realistic targets for flexible interconnection.

The second thing that sets the report apart, according to Brancucci, is that it integrates the real-world operating conditions and constraints of the transmission networks serving data center sites. To do that, they used Encoord’s software platform, which simulates how real-world transmission networks operate during all 8,760 hours of the year.

“A 500-megawatt demand will have major impacts on any utility,” said Brancucci, who co-founded Encoord in 2019 after working as a senior research engineer at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory in Colorado and as a researcher at the European Commission’s Joint Research Centre. “That will change the way power flows. And when power flow changes, you need to consider different security constraints.”

Such analyses consider not just business-as-usual conditions but also emergencies when power plants or transmission lines fail and grid operators must act quickly to prevent widespread outages. “This is the type of transmission analysis any ISO or utility is going to do when considering new load,” he said, and it’s a must-have for approving a new 500-megawatt customer.

Encoord works with transmission system operators and utilities struggling to ensure reliable service under a variety of conditions, including during winter storms when fossil gas systems fail. “If 10 utilities and 10 hyperscalers came to us and said, ‘We want to interconnect across 10 sites,’ we could redo this easily,” Brancucci said.

The results for the six sites in the December report show that transmission constraints would force four of them to curtail significant portions of their 500-megawatt peak power demand or build enough on-site generation and battery storage to cover these gaps — but only for less than 35 hours per year. The other two sites did not have transmission constraints.

The third thing that distinguishes their report is that they were able to tap into a model developed by researchers at ZERO Lab and MIT to assess how adding data centers to the grid would affect the amount of generation capacity that PJM needs to cost-effectively meet peak electricity demand.

That model enabled them to analyze how individual data centers could secure a mix of faster-to-build power sources, including solar power, wind power, and hybrid renewable-battery systems, as well as secure commitments from other customers willing to lower their power use to cover data centers’ needs through demand response or virtual power plants.

Ultimately, the new data underscores in the most definitive terms yet that flexible interconnection is viable in PJM, Atkinson said. And if PJM were to allow it, data center developers would likely be more than willing to take on the responsibility of securing their own resources to relieve those rare constraints, she added. Doing so could allow them to get online in two or three years, rather than needing to wait five to seven years for new transmission or generation.

“Data centers are willing to pay more if they can connect, in many cases, because the opportunity costs” of being forced to wait for years “far outweigh the costs of capacity,” she said. “They just need to know how much they need to build.”

And once they’re armed with that knowledge, data centers can take on the cost of securing their own resources, which would almost completely eliminate the need to build more grid infrastructure and power plants, reducing costs for all PJM customers, according to the report.

PJM isn’t the only grid operator or utility facing data center–driven cost pressures. But its challenges are more acute than most. PJM has a massive interconnection backlog that has created multiyear delays for new generation seeking to connect to its grid. And its capacity market structure is forcing up utility rates today to cover the future costs of serving forecasted data center demand.

PJM hasn’t been able to gain consensus from stakeholders — including utilities, power plant owners, big corporate energy users, and data center developers — on how to fix these problems, even as the more than 67 million customers that get power from PJM’s system face spiking utility bills to cover those costs.

That lack of consensus has prevented PJM from developing a key policy that could allow flexible interconnection to happen, Atkinson said. In order for the method laid out in the December report to work, PJM and member utilities would need to allow data centers to interconnect via something called “conditional firm” grid service.

In simple terms, this means blending traditional, “firm” service for the portion of power needs that can be supplied without grid upgrades and “conditional” service, which requires data centers to cut their power use or supply their own electricity needs during critical hours.

PJM doesn’t provide this kind of option for customers — though it may have it soon enough. In December, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission ordered PJM to create structures that would allow data centers and other big customers to connect to its grid in more flexible ways. That order set out a variety of methods for PJM to pursue, including a structure called “interim non-firm transmission service,” which closely approximates the conditional firm service that Camus and Encoord envision.

“At its core, the FERC order moves PJM away from ‘full freight’ assumptions and toward studying and serving large loads based on their actual time-varying grid use,” Brancucci said. “That’s exactly the premise behind the conditional firm service model we analyzed in a few locations in PJM.”

Similar innovations are being pursued by grid operators in the Midwest and Texas, Atkinson noted. The Department of Energy has ordered FERC to launch a fast-track rulemaking to require grid operators and utilities to expedite data center interconnections.

“Today, no market really allows you to have a mix of grid power and on-site power that’s reasonably managed,” Atkinson said. But a growing number of grid experts agree that flexible interconnection is, as she put it, “the only practical way to meet these requirements.”