The Department of Energy has closed a $1.6 billion loan guarantee for transmission upgrades in the middle of the country — a move that comes as the Trump administration slashes funding for other grid improvements, including a separate transmission megaproject in the Midwest.

The financing from the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office will go to a subsidiary of utility giant American Electric Power to overhaul around 5,000 miles of power lines across Indiana, Michigan, Ohio, Oklahoma, and West Virginia. The agency called the deal “the first closed loan guarantee” under a new “Energy Dominance Financing Program” established by President Donald Trump’s landmark tax law, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act.

Despite the Energy Dominance branding, the loan guarantee was originally announced in mid-January by the Biden administration as part of a broader $22.4 billion push to strengthen the grid using LPO funding. The Trump administration has now finalized that loan in a rare example of continuity between the administrations on energy policy.

In a statement, the Energy Department said that “all electric utilities receiving an EDF loan must provide assurance to DOE that financial benefits from the financing will be passed on to the customers of that utility.” A spokesperson for the agency did not immediately respond to Canary Media’s email requesting comment on how those assurances will be monitored and enforced.

“The President has been clear: America must reverse course from the energy subtraction agenda of past administrations and strengthen our electrical grid,” Energy Secretary Chris Wright said in a press release. “This loan guarantee will not only help modernize the grid and expand transmission capacity but will help position the United States to win the AI race and grow our manufacturing base.”

The United States needs more transmission lines to upgrade the aging grid, create room for additional power generation, and increase reliability by making it easier to share electrons across regions. Much of the U.S. grid was built in the 1960s and 1970s, and about 70% of existing transmission lines are over 25 years old and approaching the end of their typical life cycle.

Despite this, the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office canceled a $4.9 billion loan guarantee in July to finance construction of the Grain Belt Express, a major transmission project more than a decade in the works and designed to channel power from wind and solar farms in the Great Plains to cities in more densely populated eastern states.

The termination came a week after Sen. Josh Hawley, a Missouri Republican, told The New York Times that he had made a personal appeal to Trump to block the project.

“He said, ‘Well, let’s just resolve this now,’” Hawley told the newspaper. “So he got Chris Wright on the line right there.”

Hawley’s hostility to the Grain Belt Express followed a playbook that has long been deployed by actors across the political spectrum to block transmission projects, amplifying not-in-my-backyard opponents’ anger over seizures of land through eminent domain. In this case, Missouri farmers balked at the transmission route running through their land without, in their view, providing enough direct benefits.

A similar dynamic tanked construction of the 700-mile-long transmission project that Clean Line Energy Partners wanted to build to connect wind farms in Oklahoma to energy users in Tennessee nearly a decade ago, as chronicled in journalist Russell Gold’s book, “Superpower: One Man’s Quest to Transform American Energy.” In Maine, meanwhile, environmental groups teamed up with fossil-fuel companies to pass a 2021 referendum banning construction of a power line connecting New England’s electricity-starved grid to Quebec’s almost-entirely carbon-free hydroelectric system.

The Trump administration has slashed far more than just the Grain Belt Express’ funding. Since taking office, Trump has yanked billions in Biden-era loans and grants for clean-energy projects and clawed back incentives for the sector in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act. One of the few projects to receive steady funding under Trump’s Loan Programs Office has been nuclear developer Holtec International’s bid to restart the Palisades plant in Michigan, which aims to come back online before the end of the year.

The administration also in early October announced a list of billions of dollars more in clean-energy funding cuts targeted primarily at blue states — a list that included 26 grants from the DOE’s Grid Deployment Office, most of which are meant to expand the grid and boost its reliability.

Still, the latest transmission loan — along with the federal government’s AI Action Plan released in July — could signal that the administration is starting to acknowledge the importance of reinforcing the grid, said Thomas Hochman, director of the infrastructure and energy policy program at the right-leaning think tank Foundation for American Innovation.

“From the AI Action Plan to this latest loan, it’s great to see signs of this administration recognizing the centrality of the grid to AI and China competition,” he said.

LOVELAND, Colo. — For a moment, I held in my hand the cool heart of a heat pump.

I was standing inside the cavernous facility where the startup AtmosZero is building its novel steam-producing heat pumps. The all-electric technology is meant to replace the gas-burning boilers that factories rely on to make everything from Cheez Whiz to notepaper to beer. I visited the 83,000-square-foot plant on a sunny September morning to learn how AtmosZero is working to make industrial heat — but without the planet-warming carbon emissions.

The grapefruit-sized component I grasped, called a compressor wheel, helps to produce the heat that’s needed to make steam with AtmosZero’s tech, Todd Bandhauer, the startup’s chief technology officer and cofounder, explained from the factory floor.

AtmosZero opened the facility, once a mothballed Hewlett-Packard electronics plant, earlier this year to begin commercial production of its Boiler 2.0, a machine the size of a shipping container that can be hoisted by crane and plunked inside another factory.

The company has big ambitions for its electrified solution. In the United States, around 40% of the fossil fuels that factories consume is burned in boilers to make steam for processes including sterilizing equipment, breaking down wood chips for papermaking, and cooking, curing, pasteurizing, and drying food.

“Steam is the most important working fluid, both in industry and the built environment,” said Addison Stark, the startup’s CEO and cofounder. “The boiler is what drove the Industrial Revolution.”

AtmosZero spun out of Bandhauer’s research at Colorado State University in 2021, and it has since raised nearly $30 million from investors and $3.2 million from the Department of Energy to realize its steam-heat dreams. In June, the startup finished installing a 650-kilowatt pilot unit at the New Belgium brewery in Fort Collins, Colorado. At the Loveland facility, the company is working to build and deliver its first commercial heat pumps by around 2026.

The factory floor was quiet when I visited last month, with custom-made parts in open boxes or on pallets awaiting assembly. But Stark said he sees the facility getting much busier as the company works to fill demand from potential buyers, who face increasing pressure from state regulators and their own customers to slash gas-related pollution.

“I want to see electrification [across] industry and actually get ourselves on track to get to the emissions reductions that we all want to see in this century,” Stark said. In his view, “The only path to that is steam decarbonization.”

Industrial heat accounts for about 13% of U.S. energy-related carbon emissions. Much of that comes from burning fossil fuels in boilers to produce steam, though a small fraction of factories have adopted electric-resistance boilers instead. These machines can at most be 100% efficient, meaning that all the energy that goes into the boiler comes out as heat.

Heat pumps, by contrast, move heat instead of making it. The appliances use electricity and a refrigerant to gather thermal energy from someplace else — say, the open air or a water pipe — and concentrate it using a compressor to deliver the heat where it’s needed. This process can be 300% to 400% efficient or higher.

AtmosZero and a handful of other manufacturers are developing new heat pumps that will allow the technology to replace an even larger share of gas-fired boilers in factories.

Existing heat-pump models can churn out heat up to about 160 degrees Celsius (320 degrees Fahrenheit) — hot enough to cover roughly 44% of industrial process-heat energy, according to a 2022 report by nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE. New designs are expected to reach up to 200˚C (392˚F), addressing about 55% of factory heat needs.

“Being able to meet more than [half of] of industrial heat demand with a single technology is really impactful,” said Ruth Checknoff, senior project and research director at the Renewable Thermal Collaborative, a coalition of organizations working to decarbonize process heat and buildings.

At the AtmosZero factory, Bandhauer broke down how the Boiler 2.0 delivers more than hot air.

The compressor wheel I held had precisely sculpted blades that swept out in a tight spiral. When secured in the heat pump, a motor spins the wheel at up to 30,000 rotations per minute, throwing heat-carrying vapor against the equipment’s chamber walls. That increases the pressure, making the vapor hotter. AtmosZero’s heat pump utilizes two of these compression cycles, a kind of one-two punch, to ramp up the temperature enough to boil water.

Then, voila: You have steam as hot as 165˚C (329˚F).

Still, for all the apparent benefits, industrial heat pumps on the market today have struggled to gain widespread adoption. To start, they’re more expensive to install than gas boilers, which can last for decades — limiting the business case for replacing them. In the United States, fossil gas has historically been cheap enough in many places that a boiler has cost less to run than a heat pump, even though the latter uses a fraction of the energy.

States like California, Colorado, Illinois, New York, and Pennsylvania are adopting policies to help address these hurdles. That includes incentives for manufacturers to invest in tech that slashes emissions, air-quality regulations that limit pollution from their operations, and cheap financing for capital-intensive decarbonization projects. Advocates are also pushing states and utilities to work together to set more favorable electricity rates for factories.

Despite the technology’s high price tag, heat pumps can deliver significant savings on factory owners’ utility bills, according to ACEEE. A heat pump’s payback time — the amount it takes to recoup savings equal to the added installation cost — can be just a handful of years.

“We should invest time and energy into making sure that we have the right policies and enabling conditions to deploy [heat pumps] at scale,” Checknoff said.

AtmosZero isn’t the only company making steam-producing heat pumps. Other manufacturers — including GEA, Karman Industries, Heaten, Piller Blowers and Compressors, and Skyven Technologies — are proving out the tech, and some are starting to install their own machines in factories in the U.S. and Europe.

These systems often supplement existing fossil-fueled boilers by capturing a plant’s excess heat that would otherwise be wasted. That approach helps maximize a heat pump’s efficiency: Since the waste heat is already toasty, it’s easier for the tech to turn that into even higher-temperature heat for making steam.

Customers often want to actively harness this throwaway warmth to keep electric bills as low as possible, Checknoff said. But because every facility is different, installing a heat pump to slurp up that thermal energy can be costly and cumbersome.

AtmosZero is aiming for economies of scale, similar to how solar panels and home heat pumps are mass-manufactured and deployed in a modular way. “We want to bring that to the steam boiler,” Stark said during my visit.

The startup’s heat pump can be installed in a day, requiring only hookups to electricity and water lines and the factory’s control system. It’s as simple as replacing an old gas boiler with a new one, he said. And at New Belgium’s brewery, putting in the pilot heat pump this spring didn’t disrupt operations.

“They were able to continue to brew beer,” Bandhauer added.

AtmosZero’s product does have a key trade-off: It’s not as efficient as heat pumps that competitors install to harness waste heat. Those systems produce more heat with the same amount of energy. That ability is measured with what’s called the coefficient of performance, or COP. Whereas other companies’ installations might render a COP of seven or more, AtmosZero’s heat pump has a COP of up to roughly two.

But the Boiler 2.0 is cheaper to install, costing about one-tenth to one-fifth the expense of integrating a waste-heat system, Stark said. He estimated that the savings on the installation costs should enable AtmosZero’s projects to pencil out financially in five years or less.

At his desk inside the AtmosZero factory, a young engineer named Mason Mollenhauer pulled up on his computer screen a rendering of the 650-kilowatt heat pump installed at New Belgium’s Fort Collins brewery. The appliance sends the AtmosZero team, about 30 people in all, a steady stream of data.

New Belgium, the famed maker of Fat Tire Ale, is using the steam to boil wort, a sugary liquid, with bitter hops to create the libation’s flavor and aroma profile before it’s fermented into beer. When running at full capacity, AtmosZero’s heat pump is able to provide about 30% to 40% of the brewery’s steam needs.

The AtmosZero team has been carefully monitoring the New Belgium installation’s performance since June, and they’ve been able to apply lessons from the pilot project to improve their product, Bandhauer said.

While AtmosZero’s first heat-pump unit was stuffed with equipment, the latest version is roomier. The streamlined model has fewer parts, reducing costs and making it easier to service, Bandhauer said. The team is also finessing the design of its crucial compressor wheels.

Michaela Eagan, a spokesperson for New Belgium, said the brewer is focused on evaluating how the heat pump performs and hasn’t committed to any future orders.

But AtmosZero is in talks with dozens of other potential customers and is anticipating demand through 2027, Stark said. Currently, the startup’s plant contains one crane-assisted heat-pump assembly bay; that’ll grow to four. Whereas the first Boiler 2.0 took roughly three months to build, AtmosZero could be cranking out 120 to 240 heat pumps per year by 2030, he estimated.

So far, the company has primarily targeted factories for its product. But AtmosZero is also branching out into steam for other big buildings. In September, New York awarded the startup $500,000 through the Empire Technology Prize to install two of its heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton hotel in Manhattan, a project that’s still in negotiation, Stark said.

After touring the factory floor, we sat down in a nearby taproom. I asked Stark how he felt about what he and his cofounder Bandhauer were building. “Neither of us were wanting to be founders,” Stark said. “It’s a hard thing to reinvent the boiler.”

Yet “it’s rare to find an opportunity to have such a positive impact [on carbon emissions] and be profitable,” he added. “Todd and I and our whole company see that opportunity.”

A clarification was made on Oct. 16, 2025: This story has been updated to clarify that the money AtmosZero received to install heat pumps at the Midtown Hilton is through the Empire Technology Prize, a combination of private-sector and state funding.

A new law in Ohio will fast-track energy projects in places that are hard to argue with: former coal mines and brownfields.

But how much the legislation benefits clean energy will depend on the final rules for its implementation, which the state is working out now.

House Bill 15, which took effect Aug. 14, lets the state’s Department of Development designate such properties as “priority investment areas” at the request of a local government.

The law aims to boost energy production to meet growing demand from data centers and increasing electrification, while applying competitive pressure to rein in power prices.

Targeting former coal mines and brownfields as priority investment areas furthers that goal while encouraging the productive use of land after mining, manufacturing, or other industrial activity ends. Buyers are often wary of acquiring these properties due to the risk of lingering pollution.

The new law could also help developers sidestep the bitter land-use battles that have bogged down other clean-energy projects in Ohio, particularly those looking to use farmland.

Priority areas might “otherwise not see these investments, which can breathe new life into communities, improve energy reliability, provide tax revenue, and lower electricity costs,” said Diane Cherry, deputy director of MAREC Action, a clean-energy industry group.

Ohio has more than 567,000 acres of mine lands and about 50,000 acres of brownfields that are potentially suitable for renewable-energy development, according to a 2024 report from The Nature Conservancy. Federal funding to clean up abandoned mine lands has continued so far under the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law, so yet more sites may become available. Overall, remediating documented hazards at Ohio’s abandoned mine lands is estimated to cost nearly $586 million, said spokesperson Karina Cheung at the state Department of Natural Resources.

But two Ohio agencies still need to finalize rules before companies can start building energy projects in these underutilized spaces and benefiting from the new law.

The Department of Development has not yet proposed standards for approving requests to designate priority investment areas, said spokesperson Mason Waldvogel. However, in late August, the Ohio Power Siting Board proposed rules to implement HB 15, and the public comment period just closed.

Under the law, approved priority investment areas will get a five-year tax exemption for equipment used to transport electricity or natural gas. The sites will also be eligible for grants of up to $10 million for cleanup and construction preparation.

HB 15 also calls for accelerated regulatory permit review of proposed energy projects in priority investment areas. The Power Siting Board will have 45 days to determine if a permit application is complete, plus another 45 days to make a decision on it.

Those timelines are shorter than the approximately five months HB 15 allows for standard projects. And it’s substantially faster than recent projects where it took the board more than a year to grant or deny applications after they were filed.

Advocates and industry groups generally applaud the new law but want tweaks to the Power Siting Board’s proposed rules.

A big concern is making sure the board will allow wind and solar developments on mine lands and brownfields throughout Ohio, regardless of which county they’re in. Roughly one-third of Ohio’s 88 counties ban wind, solar, or both in all or a significant part of their jurisdiction. This authority was granted to them by a 2021 law, Senate Bill 52.

However, the language and legislative history of HB 15 make clear that it “was meant to be technology-neutral,” said Rebecca Mellino, a climate and energy policy associate for The Nature Conservancy.

HB 15 even states that its terms for permitting energy projects in priority investment areas apply “notwithstanding” some other parts of Ohio law.

“That clause is meant to bypass some of the typical Ohio Power Siting Board procedures — including the procedures for siting in restricted areas” under SB 52, wrote Bill Stanley, Ohio director for The Nature Conservancy, in comments filed with the board.

But the exemption provided by the “notwithstanding” clause is narrow, Mellino added, because local government authorities must ask for a priority investment area designation. That means, for example, that in a county with a solar and wind ban in place, officials would need to choose to request that a former coal mine or brownfield become a priority investment area.

The Nature Conservancy has asked the Power Siting Board to add language making it crystal-clear that renewable-energy projects can be built on any land marked a priority investment area — even if a solar and wind ban otherwise exists in a county.

Industry groups are pushing for additional clarifications to make sure the Power Siting Board meets the permitting deadlines set by the new law, both for expedited and standard projects.

For example, Open Road Renewables, which builds large-scale solar and battery storage, said in comments that, in order to align with HB 15, the board’s rules should require energy developers to notify the public of an application when it is filed, rather than after it is deemed complete.

Separate comments from the American Clean Power Association, MAREC Action, and the Utility Scale Solar Energy Coalition of Ohio ask for tweaks to provisions regarding notices on public hearings and for clarifications on application fees. The board should also promptly issue certificates for projects that are automatically approved, say comments by Robert Brundrett, president of the Ohio Oil and Gas Association.

The Department of Development hopes to finish draft standards and invite public comments on them soon, Waldvogel said. Meanwhile, the department has received its first request to designate a priority investment area. The ask comes from Jefferson County’s board of commissioners, which did not specify the type of energy that may be built in the area.

That request deals with land where FirstEnergy’s former Sammis coal plant is undergoing demolition, as well as the Hollow Rock Landfill, which received waste from the site. HB 15 gives the department 90 days to act on designation requests.

The Ohio Power Siting Board, for its part, is expected to finalize its rules within the next couple of months. Ultimately, said Cherry of MAREC Action, the law “clears the path for developers to bring energy projects online quickly and affordably, something Ohio’s consumers and businesses desperately need.”

Boston is racing to decarbonize its public housing by 2030. The latest tool it’s deploying to reach that goal? Window-straddling heat pumps.

Last week, the Boston Housing Authority announced that it’s piloting the electric technology at Hassan Apartments, a 50-year-old public housing community with 100 units for older people and adults with disabilities. The modular appliances, made by California-based startup Gradient, plug into a typical 120-volt wall outlet and will replace the apartments’ outdated, much less efficient electric-resistance system.

“We believe that low-income people and the families and individuals who live in our buildings deserve access to 21st-century technologies and home comforts, just like anyone else out there,” said Joel Wool, the agency’s deputy administrator for sustainability and capital transformation. “We’re also doing our part to reduce air pollution and combat climate change.”

The Boston Housing Authority has ordered about 100 window heat pumps for the project. Two other Massachusetts housing agencies are also piloting Gradient’s appliances, the company announced last week: the Chelsea Housing Authority, which is testing about 400 heat pumps, and the Lynn Housing Authority & Neighborhood Development, which is trying out roughly 200 heat pumps, about half of which are already installed.

Outside of Massachusetts, in 2022, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) committed to purchasing a total of 30,000 of the devices from Gradient and global appliance maker Midea over a period of seven years. The agency has been learning from an initial 72 heat pumps installed, and their performance has been positive enough that Gov. Kathy Hochul (D) announced on Friday $10 million to fund demonstration projects statewide.

Heat pumps, which are essentially reversible air conditioners, are key to electrifying heating. They provide potentially life-saving cooling, too. Because they shift around ambient heat instead of generating it anew, the appliances are routinely two to four times as efficient as electric-resistance and fossil-fuel-fired options. (Gradient claims its heat pumps are also about 50% more efficient than plain old window AC units.)

But retrofitting a building with a conventional heat-pump system can be a complex undertaking, requiring electrical upgrades and new refrigerant lines that run to individual air-handling units in each apartment, for example. Window heat pumps might require some trade-offs in terms of efficiency, but they also sidestep those serious installation hurdles.

That ultimately makes them faster and cheaper to deploy, as well as less disruptive to tenants, according to Wool. Two workers can install one of Gradient’s 140-pound heat pumps in about half an hour, NYCHA estimated, draping its saddle shape across a windowsill. And a July study by the American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy found that window heat pumps are typically the lowest-cost option for efficiently decarbonizing space heating, coming in at an average lifetime cost of about $14,500 per apartment compared to between $22,000 and $30,000 for large-scale heat-pump systems.

For its pilot, the Boston Housing Authority is paying $5,450 per residence to retrofit with window heat pumps — about one-eighth of what it has spent to update other buildings with conventional heat-pump systems: approximately $40,000 per unit, according to Wool.

Electric and gas utility Eversource is fully funding the project through the state’s energy-efficiency collaborative, Mass Save. Once the retrofit’s complete, the Boston Housing Authority expects to save up to $60,000 in energy costs per year.

In New York, window heat pumps are already making deep cuts to energy use. At the NYCHA-owned Woodside Houses, going from a gas-powered steam system to the appliances slashed the amount of energy consumed for heating by 85% to 88%, according to preliminary results from NYCHA.

“This [reduction] sounds unrealistically large,” said Vince Romanin, founder and chief technology officer at Gradient. But “we roughly know the reasons.” Waste abounds with fossil-fuel systems: Boilers don’t perfectly convert fuel into heat, steam leaks on its way to apartments, and residents, lacking control over the temperature, are prone to throw open windows if they’re overheating, he noted. User-controlled window heat pumps avoid all of those issues.

Gradient has raised more than $31 million in venture funding and signed over $9 million worth of federal and California grants to develop its window heat pumps, which it has shipped to multifamily building owners and developers in 18 states, Romanin said. He declined to specify the cost per unit.

At the Hassan Apartments in Boston, installations are already underway and should wrap up by mid-November, said Wool of the city’s housing authority. The agency will monitor energy costs closely, as it weighs whether to deploy the tech at other properties. Across its 10,000-unit portfolio, heat pumps — of the conventional variety — serve just a few hundred apartments so far.

“We do think that window heat pumps are a great technology,” Wool said. “It’s also still an early one. We want to see how it performs.”

More than a decade ago, residents of Loudoun County, Virginia, banded together to buy up treasured open space before it became a strip mall and housing development, donating the land to the Piedmont Environmental Council instead. The nonprofit has maintained it as a unique blend of cattle pasture, a nature preserve, and a community farm that donates its yield to a local food pantry.

Now, a small corner of the farm has become what organizers say is a first for the state: a crop-based agrivoltaics demonstration project. They hope the combination of solar panels and vegetable farming will showcase how much-needed renewable energy can complement, not harm, agricultural lands, at a time when data centers are demanding more and more electricity.

The Virginia Clean Economy Act requires the state’s largest utility, Dominion Energy, to stop burning fossil fuels by 2045 and to develop 16,100 megawatts of land-based renewable energy by 2035 — mostly in the form of solar.

Virginia has more than enough room to meet that target without threatening great swaths of farmland. Using a conservative metric that 10 acres of land can host 1 megawatt of solar capacity, a Nature Conservancy analysis found that the state has 40 times more suitable land area than needed for solar fields, even after ruling out over 2 million acres of “prime conservation lands” including farmland.

Researchers from Virginia Commonwealth University determined that large-scale solar today is erected on less than 1% of the state’s cropland. Under a “high-growth scenario,” that figure could rise to 3.1% by 2035, including 1.2% of the state’s federally designated prime farmland. Yet low-density residential development may pose a far greater threat to those spaces, according to research by the nonprofit American Farmland Trust, which advocates for “smart solar” that doesn’t jeopardize agricultural land.

In fact, many landowners find that renting a portion of their land to solar companies can help their farming enterprise pencil out financially, reducing pressure to sell their property to developers. An acre of land, after all, may yield hundreds of dollars if devoted to crops but thousands if leased for panels.

And yet there’s no doubt that solar has grown exponentially in the state in the last decade, and that it has disproportionately displaced farmland. Cropland makes up 5% of Virginia’s total acreage but 28% of the land area now used for large-scale solar, the Virginia Commonwealth University researchers found.

Especially in the early years of renewable-energy construction, some companies set a poor example for responsible development, said Ashish Kapoor, senior energy and climate advisor with the Piedmont Environmental Council. “It was a little bit ‘Wild West,’” he said. “Those early projects in 2018, 2019 — there were a lot of significant runoff issues.”

As solar fields have gone up at a breakneck pace — replacing plots of forests as well as farmland — opposition to them has also grown. Virginia localities approved 100% of solar projects in 2016, according to reporting from Inside Climate News. By 2024, the approval rate had fallen to under 50%.

The increasing number of rejections stems from a “a mix of disinformation and resentment,” Kapoor said. But the tension between solar and farmland is real. “That’s a national thing,” he added. “It’s everywhere.”

Agrivoltaics — the awkward portmanteau of agriculture and solar photovoltaics — has emerged as a potential solution, wherein farmland is kept in production even while it hosts solar arrays. The most common application is sheep: They graze on vegetation beneath the panels and prevent the need for expensive and polluting mowers. Planting flowers in and around panels to supply honeybees and other pollinators is also popular.

Still, the Piedmont Environmental Council team wanted to experiment with a crop-based model because it fits better with what most farmers in the area are doing now: raising vegetables.

“You want to change as little as possible for the farmer,” said Teddy Pitsiokos, who manages the organization’s community farm.

Occupying a quarter-acre section of the nonprofit’s 8-acre community vegetable farm in Loudoun County, the agrivoltaics project is small by design. It features 42 ground-mounted solar panels with a total capacity of 17 kilowatts, two batteries for backup power during outages, and about 2,000 square feet of growing area.

The array will supply more than enough power to meet the farm’s needs, with additional headroom for a planned EV charger and a greenhouse that organizers want to electrify eventually. But the Piedmont Environmental Council isn’t trying to demonstrate scale. Rather, it hopes to carefully measure impact.

With the shade and protection from rainwater that they provide, how do the solar panels affect soil moisture and temperature? What’s the resulting crop yield? What do vegetables grown beneath and near solar panels look like, and how will consumers react? Do any contents from the panels make their way into the crops, posing health problems?

Most research has found that the answer to the last question is no. But the team still plans to test for contaminants in response to public concern as a show of good faith and transparency, and in an effort to address any potential barriers to agrivoltaics from the get-go.

While most crop-based agrivoltaics projects involve growing produce in the ground, the Piedmont Environmental Council’s farm also includes raised beds, which enable educational tours and widen the demonstration project’s relevance.

The beds do increase costs, said Pitsiokos. But the rationale for them, he said, “is so we can create data for people who might be doing this in an urban setting, a parking lot, or on some other nonpermeable surface,” he said. “We have productive agricultural soil; not everybody does.”

The experiment could also help inform compliance with new state rules designed to mitigate land loss from solar: Certain developers have to conserve land on a one-to-one basis for projects on prime farmland, but their burden is less if the array is used for agrivoltaics.

Pitsiokos also wants the data to reach educators, policymakers, and cohorts he hasn’t anticipated yet. “We want to share it with everybody,” he said, “because we know that we can’t predict who might benefit from it exactly.”

Perhaps most of all, the Piedmont Environmental Council hopes the project will reach farmers. Plenty are outspoken on solar, both for and against. But a 2024 survey from the American Farmland Trust found that most Virginia farmers and farmland owners hold nuanced views. Over half would consider solar if they could continue farming under and around the panels, according to the survey, but nearly two-thirds agree that solar developers should be responsible for returning land to a farmable state after an array is decommissioned.

With the project’s first crops of kale getting harvested this month, the Piedmont Environmental Council plans to make real-time data available as soon as this winter, for all to see. But grand conclusions won’t be forthcoming for another two or so years.

“Like with all scientific experiments,” Pitsiokos said, “slow is actually good.”

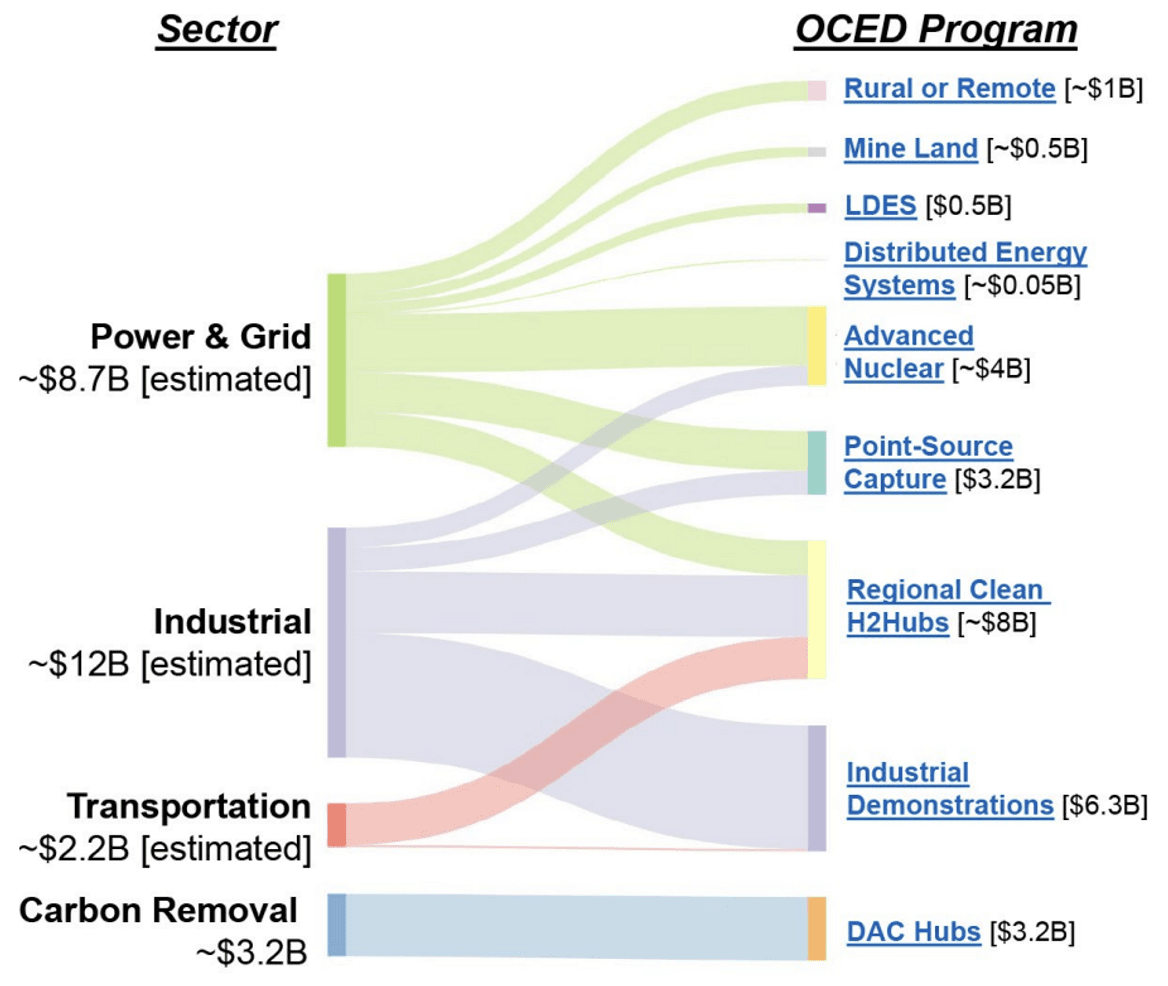

The Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations was supposed to be a launchpad for ambitious projects to help America lead the way on cleaner power and manufacturing. Now it’s been reduced to a shell of itself.

As the Trump administration slashes spending and fires workers across the federal government, the U.S. Department of Energy has emerged as one of the hardest-hit agencies — and perhaps no other of its divisions has been singled out as deliberately as OCED.

It’s a dramatic reversal for the four-year-old office. During the Biden administration, Congress endowed it with nearly $27 billion to try to scale up cutting-edge technologies that could curb planet-warming pollution from industrial facilities and power plants. Trump officials have in recent months hollowed out the office, canceling billions in previously issued awards for everything from low-carbon chemical manufacturing to rural energy resiliency, while also dismissing over three-quarters of its employees.

The situation is best summarized by the budget the White House has requested for OCED for the next fiscal year: $0.

Experts and insiders warn that the tumult within OCED and the DOE more broadly is eroding the private sector’s trust in the federal government and its ability to drive energy innovation.

“The administration has really created a chilling effect on the willingness of future early-stage technology developers to work with the Department of Energy,” said Advait Arun, a senior associate for energy finance at the Center for Public Enterprise, a nonprofit think tank.

Ultimately, that will stifle investment not only in the clean energy sectors the Trump administration dislikes but in those it has championed as well, such as advanced nuclear and geothermal. Former OCED staffers and contractors, who were granted anonymity to speak freely, told Canary Media that the disruption is a major setback for America’s efforts to launch the world’s next generation of energy technologies and industries.

“We are eliminating ourselves as a leader in the clean energy space, especially for the industrial complex,” one person said. “What I’m seeing is China is about to slip right into that position. Just logically and economically, I don’t understand the steps that are being taken.”

Congress created OCED in December 2021 to help deploy first-of-a-kind projects at commercial scale. The idea was for the government to absorb some of the risks and provide early capital to usher companies across the valley of death that lurks between promising research pilots and real-world operations that can move the needle on decarbonization.

The 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law provided OCED with about $21 billion over five years to scale up emerging technologies like small modular reactors and long-duration energy storage, and to advance ambitious “hubs” for producing hydrogen fuel and capturing carbon dioxide from the sky and smokestacks. In 2022, Congress gave OCED an additional $5.8 billion through the Inflation Reduction Act to help decarbonize U.S. manufacturing of materials like steel, cement, and chemicals.

“A lot of this stuff is a chicken-and-egg situation, where the private sector doesn’t want to come in [and invest] yet because it’s not proven,” said Zahava Urecki, a senior policy analyst with the Bipartisan Policy Center’s Energy Program.

“But we need the technology to go through this [demonstration] process in order to make sure it becomes proven, so that eventually we can have this in society,” she added. “And that’s where the federal government plays a key role.”

Over the course of three years, the office selected 116 projects in 42 states to receive over $25 billion in federal funding. For most awards, participating companies were required to cover at least 50% of total costs themselves — meaning the office expected its portfolio to spur nearly $65 billion in private investment, in addition to creating potentially hundreds of thousands of jobs.

Among the biggest winners were seven regional hydrogen hubs and two major direct-air-capture initiatives that would remove CO2 directly from the sky. The choices were not always broadly celebrated, and critics raised concerns that the hydrogen and carbon-capture initiatives in particular would do more harm than good for the climate by propping up unproven, energy-intensive projects involving fossil-fuel companies.

But other OCED picks garnered more public applause — and supported industries that President Donald Trump had flagged as priorities. In 2024, the office selected Cleveland-Cliffs for an award of up to $500 million to begin lower-carbon steel production in Middletown, Ohio, the hometown of Vice President JD Vance. Another manufacturer, Century Aluminum, got up to $500 million to help it build the nation’s first new aluminum smelter in decades, which would be powered by carbon-free electricity.

Former OCED staffers said they attempted to brief the incoming Trump administration on the office’s portfolio and to explain how they could support the president’s stated goals of boosting “American energy dominance” and “advancing innovation.”

However, from the time Trump took office on Jan. 20, “It became pretty clear that it didn’t really matter,” a former employee said.

It was quickly evident that Trump would, in fact, be adopting the right-wing policy platform Project 2025 after trying to distance himself from it on the campaign trail. The blueprint — which outlines ways to erase federal spending — called for eliminating “all DOE energy demonstration projects, including those in OCED,” in order to avoid “distorting the market and undermining energy reliability.”

For one staffer, “it all started crumbling” on Day 1, when the White House issued an executive order to halt federal work on “diversity, equity, and inclusion” — a measure that affected OCED’s grant recipients. Under former President Joe Biden, the office required participants to create community-benefit plans to ensure the billions in taxpayer dollars went to projects that included neighbors in the planning process and supported local economies. Under Trump, the strategy became a liability.

A blitz of federal funding freezes and layoffs — and court reversals and injunctions — then ensued, creating chaos across federal agencies and for all the outside companies that hold or held government contracts. In late January, the White House extended federal workers a “deferred resignation offer” that would allow people to resign from their jobs and go on leave with pay through Sept. 30, the end of the fiscal year.

Few OCED staffers initially took the offer. But after several months of chaos, about 77% of workers at OCED signed the deal when the White House extended it again in April. Insiders say that figure is likely even higher now. Across the DOE, some 3,200 employees within the agency’s roughly 17,000-person workforce opted to leave.

“That’s when folks at OCED actually started to realize it was going to be personnel changes that would first impact the projects, and not the program cuts,” according to a former employee.

On May 15, about a month after the staff exodus, Energy Secretary Chris Wright said the DOE would begin scrutinizing federal grants to “identify waste of taxpayer dollars.”

The agency started requesting additional information for 179 awards totaling over $15 billion, with a focus on large-scale commercial projects. Wright claimed that these awards were “rushed out the door, particularly in the final days of the Biden administration,” and required further review to ensure that individual projects were “financially sound and economically viable.”

Less than 3% of the over $25 billion in OCED’s awards portfolio had actually been paid to projects as of March 31, in part because larger grants were meant to be doled out in tranches over a long development timeline, according to EFI Foundation, a nonpartisan organization led by Ernest Moniz, who served as energy secretary during the Obama administration.

Project developers interviewed by EFI claimed that, contrary to Wright’s statement, OCED’s “due diligence was more rigorous than what private-sector investors would conduct” and that, rather than undergo the office’s laborious process, “faster decisions would have better aligned with developer timelines,” the foundation said in a June report.

Wright didn’t wait long to begin nixing projects. In late May, he announced the termination of 24 awards issued by OCED totaling over $3.7 billion, including funding for carbon capture and sequestration and projects within the office’s Industrial Demonstrations Program that aimed to reduce emissions from iron, cement, glass, and chemicals production.

“These clean energy projects were enshrined into law by bipartisan majorities and represent the will of Congress,” Sen. Martin Heinrich, Democrat from New Mexico, said in a recent statement to Canary Media. Heinrich and other congressional Democrats sent a letter to Wright on Sept. 9 accusing the DOE of undertaking a “haphazard, disorganized, and politically driven” cancellation process.

More funding cuts arrived earlier this month, when the DOE said it was slashing 321 grants for projects almost entirely in states that voted for Democratic nominee Kamala Harris in the 2024 presidential election. A spreadsheet of the cuts lists 11 newly affected OCED projects totaling nearly $2.5 billion, including for two major hydrogen projects planned in the Pacific Northwest and California. The October list also repeats five OCED-backed initiatives that first appeared in the May announcement.

Project developers have said they’re appealing the award terminations and are in continued talks with the DOE. Still, it’s unclear how much capacity the office has anymore to helm those discussions.

Wright said in an Oct. 3 interview that more cancellations would follow, and early last week rumors swirled about a second spreadsheet that appeared to outline deeper cuts for carbon-removal projects, hydrogen hubs, and other OCED projects. The nature of the list remains unclear, but if it proves to be a signal of cuts to come, it would cancel another $6.1 billion in awards from OCED.

The project areas that have yet to be cut — or to appear on any potential hit lists — include advanced nuclear energy and critical minerals. Additionally, the energy agency said it has started tapping OCED’s authority to make some new grants for Trump’s favorite energy source: coal-fired power plants. Should the office shutter, these awards would likely be managed by other divisions within the DOE.

Alex Kizer, a senior policy advisor at EFI, noted that gutting OCED won’t end America’s efforts to decarbonize heavy industries.

In the case of cement and steel, demand for low-carbon materials is growing within U.S. and global markets as tech giants look to build less carbon-intensive data centers, and as state governments and European and Chinese regulators work to rein in industrial pollution. Still, losing grants — and the DOE’s seal of approval — will undoubtedly make it harder and more expensive for companies to raise private capital for commercial-scale projects. Stifling the DOE’s role as a gatherer and publisher of real-world lessons could further slow progress, Kizer said.

“The potential for breakthrough across different energy sectors is so significant,” he said of OCED’s work, noting that “a relatively small investment from taxpayers could have an enormous benefit to taxpayers over time,” in terms of delivering cleaner, more reliable energy. “Who says no to that?”

Barbara Kelley remembers when her car and windows were routinely coated with a thin film of coal dust that had drifted over from the power plant on the edge of her neighborhood in Salem, Massachusetts. She remembers the noise as a conveyor belt lifted the coal into the building. She also remembers how pleased she was when the community started to discuss the possibility of building an offshore wind terminal on the site when the plant eventually closed.

“The coal plant — it worked, it gave us energy, but it was time to change,” Kelley said. “My reaction was, having a wind port is part of having wind energy — and that’s a good thing.”

In the years since the coal plant shut down in 2014, Kelley and many other community members have worked to promote the goal of transforming part of the property into a staging ground where wind turbine blades, tower sections, and nacelles can be prepared for transport to offshore construction sites south of Cape Cod and north in the Gulf of Maine. The vision was to turn Salem Harbor, one of the country’s oldest ports, into a linchpin of the then-burgeoning offshore wind industry and provide an economic boost to some of Salem’s most disadvantaged residents.

Last year, that dream seemed close at hand. City and state leadership had embraced the idea. The state had promised a hefty investment, and the Biden administration had awarded the project a sizable grant. Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey attended a groundbreaking ceremony for the development in August 2024, and operations were expected to begin in 2026.

Project developer Crowley had agreed to pour nearly $9 million into a community benefits agreement that included job training, childcare, emergency services, and local sustainability and resilience efforts. Planners estimated construction and operations would create hundreds of jobs. And the whole process of bringing the idea to life gave community members a sense of agency and hope for their city.

Then this August the Trump administration announced that it would cut off $679 million in federal funding for offshore wind ports. The move was part of President Donald Trump’s ongoing attacks on offshore wind, the impacts of which are being felt far beyond the nascent sector. Now, like those in so many communities across the country, the people of Salem find themselves facing the fallout of national political priorities, and wondering whether more than a decade of work will ever bear fruit.

“I feel like we’re all a little bit in the dark still,” said Lucy Corchado, a local activist who was part of the group that negotiated the community benefits agreement. “I hope we hear some good news, but I’m not sure that’s going to happen.”

Community advocates first started floating the idea of building a wind port on Salem Harbor roughly 15 years ago. At the time, plans were underway to build a commercial wind farm off Cape Cod, and the coal plant’s closure looked likely. The advocates saw a promising future for the large industrial waterfront parcel in what seemed to be a growing energy sector.

Once the epicenter of the spice trade in early America, Salem has a deepwater port that today serves mostly recreational boaters, tourist outings, and the occasional cruise ship. Though the city is home to a hospital, university, and thriving hospitality sector, it also has a median household income well below the average in most surrounding towns and statewide.

When the owner of the coal plant proposed building a natural gas–burning facility on the site, activists from Salem Alliance for the Environment, or SAFE, were skeptical of replacing one fossil fuel with another. However, they decided not to oppose the plan for a new, smaller plant and to instead push for the rest of the property to be used for an offshore wind port that could both contribute to the decarbonization of the grid and create new opportunities for local residents.

“It wasn’t that we were really supportive of the gas plant, but we had bigger dreams of a wind port coming into town,” said SAFE founder Patricia Gozemba. “Our dream played out.”

In 2022, then-Gov. Charlie Baker, a Republican, announced the state would make a $75 million investment in the port, and the project was also awarded a $34 million grant from the federal Port Infrastructure Development Program. Two years later, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center bought 42 acres of the former coal plant property, with the intention of leasing it to energy and marine developer Crowley. The City of Salem acquired five adjacent acres.

The plans enjoyed widespread support in the city.

“We’re a uniquely progressive community,” said SAFE executive director Bonnie Bain. There was no organized opposition to the wind port idea beyond occasional grumbling by Facebook commenters, she said.

As negotiations between Crowley and the city got underway, SAFE and other groups started to worry that, despite their longstanding advocacy for the project, important community input was missing from the process.

“This wasn’t just a wind port — it was an investment in the community,” Bain said. “We want to make sure that when we build projects that they enhance the community.”

Advocates raised their voices, submitting testimony for state and local proceedings, attending planning board meetings, and hosting educational webinars about offshore wind. In 2023, SAFE and several Salem neighborhood associations and civic groups formed a coalition to ask for a seat at the bargaining table as the city and developer hammered out the community benefits agreement.

The coalition was determined to make sure that the project didn’t harm nearby residents and created opportunities for some of the city’s disadvantaged populations. The group met once a week — Thursdays at 4 p.m. — for a year to discuss strategy, write letters to the media, and plan for local and state meetings. Salem Mayor Dominick Pangallo agreed to include two coalition members — Kelley, representing the Historic Derby Street neighborhood adjacent to the planned port, and Corchado, representing The Point, a largely immigrant, lower-income neighborhood nearby — in the community benefit negotiations.

“We kind of pushed our way to the discussion table to make sure they heard what we were looking for,” Corchado said.

The parties struck a deal that included a range of measures. The city’s public schools were set to receive $40,000 annually for technical and vocational education programs and another $50,000 per year to expand prekindergarten childcare to help parents attend job training. Crowley also committed to offer paid apprenticeships and internships, help graduating students find jobs in the industry, and fund scholarships for local workers to access relevant training opportunities.

When Trump was elected in 2024, some port supporters held out hope that the project would escape the president’s well-known hostility to offshore wind. Corchado, however, was concerned from the beginning.

“We were so far along and the funding has already been secured. It was like, maybe it’s not going to be that bad,” she said. “But, yeah … it’s what I was worried about.”

The news on Aug. 29 that the federal funding would be terminated was an enormous disappointment for proponents. It also left them with questions about whether the lost funds would scuttle the plan entirely, force the developer to change course, or merely delay implementation. Crowley will say only that it is reviewing the action and determining next steps. The city of Salem is also figuring out what to do now.

“We are still working to pursue all avenues to address the funding termination,” the mayor’s office said in a statement. “That includes working to get it restored or, failing that, looking at how we could revise the project plan to account for the loss of what was around 10% of the expected construction costs for the port.”

Community members are feeling somewhat adrift as the concrete plans they invested so much time in become increasingly uncertain.

“It wasn’t necessarily surprising,” Bain said. “But it’s still dizzying when it actually happens.”

An enormous solar project planned for the Nevada desert was canceled last week while awaiting final federal approvals, an ominous sign for renewables development on public lands under the Trump administration.

Esmeralda 7 was unique for its size: It would have installed 6.2 gigawatts of solar generation and 5.2 gigawatts of battery capacity across 62,300 acres of Nevada desert. No other solar project in the U.S. comes close to that scale. It was also a test case for a new, more efficient approach to federal permitting, one that promised to get clean energy infrastructure built more quickly.

The solar colossus incorporated seven distinct solar-and-battery projects from different developers on adjacent parcels of land overseen by the federal Bureau of Land Management. Instead of each going through an exhaustive process to attain federal permits, the projects banded together to undergo a joint analysis by the BLM. The bureau completed a draft environmental review of the megaproject under the Biden administration, but didn’t release a final version. Instead, as first reported by Heatmap, the BLM website switched the project status to “canceled” on Thursday.

It’s not yet clear if the decision to cancel was made by the BLM or Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, or if the Esmeralda 7 developers pulled out, perhaps based on conversations with the government. An automated email reply from Scott Distel, the BLM contact for the project, said he is not authorized to work during the government shutdown and thus was unable to respond.

The BLM circulated a statement to media on Friday saying that “applicants will now have the option to submit individual project proposals to the BLM to more effectively analyze potential impacts.” Such a move would entail repeating the already-conducted environmental analysis for each project individually, after which the administration could simply move to cancel the projects again.

“While we await further clarity from BLM on its apparent decision to abruptly cancel these solar projects in the late stages of the review process, we remain deeply concerned that this administration continues to flout the law to the detriment of consumers, the grid, and America’s economic competitiveness,” Ben Norris, vice president of regulatory affairs at the Solar Energy Industries Association, wrote in a statement Friday.

President Donald Trump swept into office declaring an “energy emergency” and pledging to unleash more American energy and bring down prices. Since then, though, his administration has intervened to obstruct several major power projects that would deliver renewable electricity to the grid at a time of swiftly rising power demand.

The White House attempted to halt two fully permitted offshore wind farms, the 810-megawatt Empire Wind 1 and the 704-megawatt Revolution Wind. Offshore wind requires permissions from the Interior Department’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, giving the administration leverage over this type of private enterprise. Those efforts to stop construction did not hold up, but they incurred millions of dollars of unanticipated costs for the developers, and damaged the country’s reputation as a safe place to invest in billion-dollar infrastructure projects.

Currently, only 4% of terrestrial, utility-scale renewable capacity sits on federal land, according to the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. But in the U.S. West, many federal parcels are well-suited for renewable energy; if these sites were successfully developed, they could greatly increase clean energy production.

Esmeralda 7 appears to be the first large renewable development on public lands to be officially canceled during the Trump administration, said Ted Kelly, director and lead counsel for U.S. clean energy at the Environmental Defense Fund.

Previously, he added, some projects that were expected to move forward were “sitting in limbo,” neither canceled nor approved on schedule. Now, Kelly said, there’s “a real concern” that public lands may be effectively off limits for wind or solar development for the duration of the Trump administration.

While it lasted, Esmeralda 7 modeled a new, more streamlined way to analyze a huge amount of renewable capacity.

“It increases efficiency on the government side, not having to recreate the same review of the same type of impact over and over again,” Kelly noted. Combining the permitting also helps in scrutinizing the cumulative effect of multiple projects, something environmental advocates have pushed for.

The BLM released its draft environmental impact statement in late July 2024, kicking off a 90-day comment period, which included an in-person public meeting and an online one.

The project would have impacted the desert landscape. But the draft environmental review identified those impacts and outlined mitigation efforts needed to protect endangered species and minimize disruption to desert plants. Esmeralda 7 also would have had environmental benefits by displacing polluting power production with emissions-free generation.

Projects that undergo thorough vetting and abide by the government’s conditions have a legal right to move forward, Kelly said. Under U.S. law, the government can’t cancel a project without mustering a set of reasons and evidence; the Administrative Procedures Act forbids “arbitrary and capricious” decisions that violate due process.

“It’s inconsistent with the law, but it’s also obviously inconsistent with what our country needs,” Kelly said of the cancellation.

Several prominent voices outside the clean energy industry expressed alarm at the news. Utah’s Republican Gov. Spencer Cox blasted the cancellation on X, writing, “This is how we lose the AI/energy arms race with China. … Solar with batteries can now be close to baseload power and we should keep these projects rolling until we get the gas/nuclear/geothermal plants we need.”

Billionaire John Arnold, who made a name for himself as a gas trader at Enron, also tweeted about the cancellation, saying, “I’m increasingly worried we’re headed for the cliff.” Coal, hydropower, and nuclear are not projected to grow much in this decade, he noted, so “all growth has to come from gas, solar & wind.”

Halting new wind and solar developments thus threatens the country’s ability to grow electricity supply even as AI companies and leaders in other industries are in desperate need of more power.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Renewable energy just notched a major milestone.

Worldwide, renewables produced more electricity than coal across the first half of this year — a first, according to clean-energy think tank Ember.

The global revolution in solar deployment made the milestone possible. The energy source more than doubled its share of global electricity generation over the last four years alone, rising from 3.8% in 2021 to 8.8% in the first half of 2025. Wind power also grew modestly during the first half of the year.

Taken together, the two clean-energy sources increased fast enough to not only meet all new electricity demand in the first six months of 2025, but to displace a bit of fossil fuel use as well.

Despite the progress, coal remains the single largest source of electricity in the world. No renewable-energy source on its own — be it wind, solar, hydro, or bioenergy — measures up to coal. And although renewable energy on the whole has now surpassed coal, it’s not like coal generation is plummeting. Power plants still plowed through more coal in the first half of this year than they did in the first half of 2021.

But coal power is stagnant. Meanwhile, renewables, and solar in particular, are ascendant. This latest milestone is worth celebrating not because fossil fuel use has been dealt a fatal blow, but because it’s a clear illustration of the trajectory each energy source is on.

For the world to truly reorient itself around energy sources that don’t bake the planet and spew toxic fumes into the air, those trends must not only continue but accelerate. Coal — and eventually gas — will need to decline as assuredly as renewables soar. Let’s call this a step in that direction.

This analysis and news roundup comes from the Canary Media Weekly newsletter. Sign up to get it every Friday.

The specter of additional, deeper federal funding cuts is haunting the clean-energy sector. A Department of Energy list shared this week with Canary Media suggests the agency is thinking about canceling a whopping $23 billion worth of energy projects.

Well, maybe.

Here’s what we know for sure: Last week, the DOE terminated $7.56 billion in federal funding for grid upgrades and energy projects, which were largely set to benefit Democratic-voting states. Right after, Energy Secretary Chris Wright called the announcement a “partial list” and promised that more cuts were coming — in both blue states and red ones.

From there, it gets fuzzier.

On Tuesday, sources shared a leaked spreadsheet with Canary Media that looks a lot like a follow-up to last week’s hit list. It lists the word “terminate” next to not only the 321 grant cancellations from last week, but hundreds of other projects too.

But despite headlines declaring this a new wave of grant cancellations, the exact nature of the list remains murky. A former DOE official who spoke on condition of anonymity told Canary Media’s Jeff St. John that the list is legitimate and that it represents the grants DOE officials have recommended for cancellation to the White House.

DOE, meanwhile, hasn’t confirmed the list’s authenticity and denies that it has yet decided to cancel any of the projects that appear only on the second list. In a statement, the DOE said it is still conducting an “individualized and thorough review of financial awards made by the previous administration,” and that “no determinations have been made other than what has been previously announced.”

Recipients who appeared only on the second list also say they haven’t heard that their grants will be canceled.

Vikrum Aiyer, global policy head at carbon-capture startup Heirloom, whose major direct-air capture project was included on the second list, told Canary Media’s Maria Gallucci that the company wasn’t “aware of a decision from DOE” to cancel its federal award.

Alliant Energy, a utility holding company whose Wisconsin Power and Light subsidiary was listed on the new spreadsheet, said in a statement that it has not been made aware of changes to its DOE grants.

And aside from the two blue-state hydrogen hubs whose funding was cut last week, several of the firms working on the other five hubs have yet to receive cancellation notices, Alexander C. Kaufman reports.

At best, the latest leaked list is just another layer of chaos and uncertainty for federal funding recipients, who are stuck trying to get answers about the status of their projects from a department that has been depleted by layoffs. At worst, though, it’s a harbinger of billions more in cuts to come for innovative American energy projects.

— Jeff St. John, Kari Lydersen, and Alexander C. Kaufman contributed reporting.

State and federal hurdles pile up for community solar

Community solar is in trouble, and it’s not just because of federal shakeups, Canary Media’s Alison F. Takemura reports. These shared arrays help make solar power accessible to those who can’t put panels on their own roofs, whether that’s because they rent, can’t afford them, or face other barriers. That power can in turn help households reduce their bills.

But the One Big Beautiful Bill Act signed in July set an early sunset for tax credits that can cover as much as half of a community solar array’s cost. And states are also contributing to the decline. Developers in New York, a major community solar market, are facing higher costs for land and permitting, while in Maine, developers have to reckon with changes to its solar net-metering program, as well as lowered compensation and new fees for community solar projects.

Those state challenges, combined with the looming threat of more federal funding cuts, have all led Wood Mackenzie to reduce its forecast of new community solar installations by 8% through 2030.

Global clean energy keeps growing

Two new reports contain some good news for clean energy around the globe. For starters, solar and wind installations outpaced global power demand growth in the first half of this year, according to an analysis out this week from think tank Ember. And in a first, renewables also generated more power than coal over the same period.

The International Energy Agency meanwhile predicts renewables’ global expansion will continue. Renewable power installations will more than double by 2030, it forecasts, with solar accounting for 80% of that new generation. That’s some fast growth, but it’s still well short of the tripling the agency has called for to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

Clean power down under: Australia’s grid operator says replacing its coal-dominated system with 100% renewables is not just a climate-conscious choice, but the lowest-cost choice as well. (Canary Media)

Actual good news for wind: Dominion Energy’s Virginia offshore wind project is on track to start delivering power by March 2026, and is set to be the country’s biggest by far when it’s completed at the end of 2026. (Canary Media)

Tesla’s new price point: Tesla announces a cheaper version of its Model Y SUV and its Model 3 sedan, both with base models starting below $40,000. (CNBC)

Fighting for solar: A labor union, solar installation companies, nonprofits, and other groups sue the Trump administration over its rollback of the $7 billion Solar for All program. (Associated Press)

Coal’s collapse: A low bid for a federal coal lease and the early shutdown of New England’s last coal power plant showcase how the fuel’s economic case continues to shrink even as the Trump administration tries to prop the industry up. (Associated Press, Canary Media)

A windfall for storage: Battery storage startup Base Power raises $1 billion to expand its mission of building home battery systems that it leases to households and uses as a grid resource. (Canary Media)

Weatherization works: Efficiency programs in New England and New York are set to save residents tens of billions of dollars, even as states face pressure to cut spending on such efforts in the name of short-term bill savings, a new report concludes. (Utility Dive)

A correction was made on Oct. 10, 2025: Heirloom has a direct-air carbon capture project, not a hydrogen-hub project.