Everyone agrees that California’s major utilities are charging too much for electricity. But as in previous years, state lawmakers, regulators, and consumer advocates are at odds over what to do about it.

With the state’s three biggest utilities reporting record profits even as customers’ rates have skyrocketed, critics say the time is right to pass laws that will force regulators to more tightly control key utility costs — or even outright curb utility spending and profits.

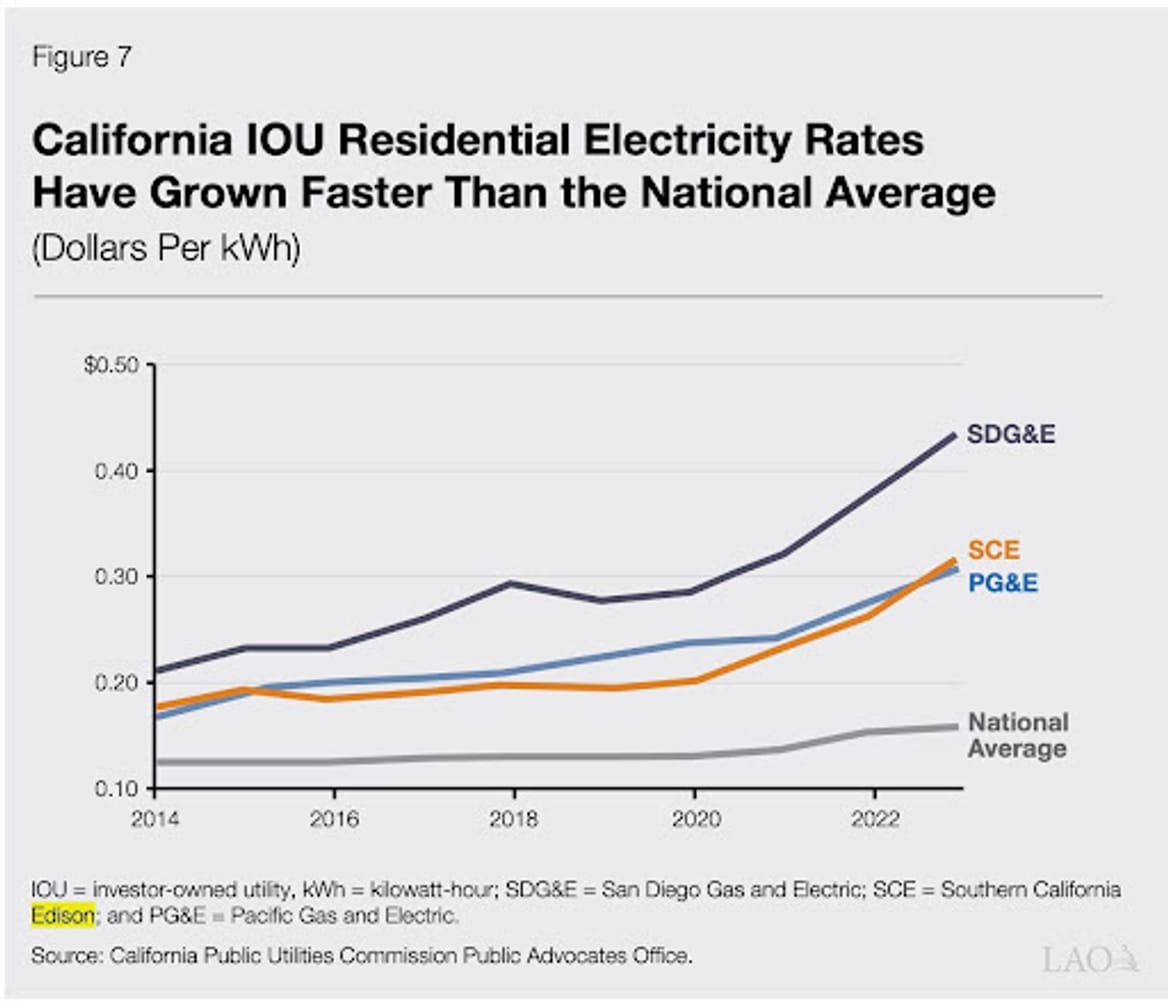

Customers of Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric now pay roughly twice the national average for their power, with average residential rates rising 47% from 2019 to 2023, according to a January report from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

Rates are set to climb even further in the coming years as utilities look to expand their power grids to meet growing demand from data centers, electric vehicle charging depots, and millions of households buying EVs and heat pumps. Utilities also need to build high-voltage transmission lines to connect far-off clean energy resources to population centers. And they need to harden and protect thousands of miles of low-voltage power lines to prevent deadly wildfires in a landscape that’s growing more susceptible to conflagration because of climate change.

Utilities are allowed to earn a profit on these infrastructure investments and to pass the costs onto customers — but only within reason. It’s the job of regulators to ensure that profits aren’t disproportionate to what utilities charge ratepayers.

Consumer advocates are now demanding that the California Public Utilities Commission be more aggressive in challenging PG&E, SCE, and SDG&E’s spending plans, which have allowed them to earn more profits than ever over the past year. In October, Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) ordered the CPUC to issue a report on how to curb rate increases.

“There’s agreement that record-breaking shareholder earnings make no sense along with skyrocketing costs,” said Mark Toney, executive director of The Utility Reform Network (TURN), a ratepayer advocacy group, and that “utilities need to be held more accountable for their spending.”

TURN is supporting a list of bills being introduced in this year’s legislative session that take aim at utility costs. Some would increase state regulator oversight on utility grid spending. Others seek to forbid utilities from spending ratepayer funds on lobbying and advertising and strengthen CPUC oversight of potential “double recovery,” or utilities collecting funds for projects already financed via other means.

Beyond TURN’s list of favored bills, there are more aggressive legislative proposals that would limit utility rate increases to no higher than the general rate of inflation and force utility shareholders to pay more into a state fund created to shelter utilities from bankruptcy as a result of having to pay for catastrophic wildfires caused by their equipment. PG&E was forced into bankruptcy in 2019 under these conditions after a failure of one of its power lines sparked the state’s deadliest-ever wildfire in 2018.

Legislation that would order the CPUC to increase oversight of utility spending or limit the costs utilities can pass on to customers faces an uphill battle. Last year, a number of reform proposals faltered in the face of heavy lobbying from utility workers unions and pushback from utilities, which spend generously on state political campaigns.

But with customers of California’s three big utilities now paying the highest rates in the nation outside Hawaii and one in five California households struggling to pay their monthly bills, the public pressure to do something may outweigh utility lobbying muscle, advocates say.

Last month, the California state Senate Energy, Utilities and Communications Committee held a legislative hearing where the CPUC briefed lawmakers on its new report on how to contain rate increases.

That report shied away from suggesting major clawbacks in utility spending or limiting profits. Instead, it focused on shifting some costs now passed through to ratepayers — including payments to customers who have rooftop solar, wildfire mitigation and recovery investments, and programs that boost energy efficiency and help low-income customers pay their bills — to “other sources of funding.” That could include state taxpayers, California’s cap-and-trade program, or customers of publicly owned utilities.

All of these proposals would require legislative action, and some lawmakers pushed back on the idea that utilities should be able to shift costs that are their responsibility under law. But CPUC President Alice Reynolds said the alternative — forcing utility shareholders rather than ratepayers to bear more costs — could violate legal precedents that allow utilities a “reasonable rate of return to attract investment in the system,” as she put it.

State Sen. Josh Becker (D), chair of the committee, said during the hearing that legislative leaders and Gov. Newsom’s office plan to put together a bill focused on energy affordability in the coming months.

Toney said he’s hopeful this affordability package “has some of the proposals that went down at the last minute last year, and that there’s going to be a lot more support for them” this year. But he was also critical of the CPUC’s report. “I’ll tell you what was missing” from it, he said — “any conversations about utility profits.”

PG&E, the state’s biggest utility, has reported record-breaking profits over the past two years. The average customer bill increased more than 35% between 2021 and 2023, and CPUC approved six PG&E rate hikes in 2024. The utility’s rates will increase again this year to cover the cost of keeping the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant open.

SCE, the state’s largest electric-only utility, reported record-setting profits in 2024, after winning CPUC approval for rate hikes last year. Another rate hike was approved in January.

SDG&E reported profits near its all-time high last year after record-high profits in 2023 and 2022. The utility’s rates have increased to become among the highest in the nation, as shown in this chart from the state Legislative Analyst’s Office.

The CPUC’s report stated that “the biggest drivers of rate increases” are “the growth in spending to address wildfire mitigation” as well as “the cost shift that results from legacy Net Energy Metering programs,” which compensate customers with rooftop solar systems for electricity they send back to the grid. The CPUC delegated to secondary status the costs of “energy transition related investments in transmission and distribution infrastructure.”

But rooftop solar incentives don’t deserve most of the blame for rising rates, said Loretta Lynch, an attorney and energy policy expert who served as CPUC president from 2000 to 2002. She is also a longtime critic of the current CPUC commissioners appointed by Gov. Newsom.

Instead, she said during a February webinar presenting new data on the connection between utility spending and rising rates, “the primary drivers of a vast majority of the costs over the last five to 10 years have been extraordinary procurement” of clean energy at the early stages of the state’s energy transition, when solar power was far more expensive than today, and, more notably, “the tripling of the costs of transmission and distribution” grid investments over the past decade.

Other energy analysts, including some who strongly disagree with Lynch’s views on rooftop solar, share this perspective on the grid’s role in driving up utility costs.

Severin Borenstein, head of the Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, is a major backer of the proposition that rooftop solar is causing bills to rise for other customers. He reiterated that position in a February presentation to the Little Hoover Commission, an independent state oversight agency, noting the significant costs of “public purpose programs,” such as the billions of dollars that utility customers at large pay to support rooftop solar incentives and low-income ratepayer assistance.

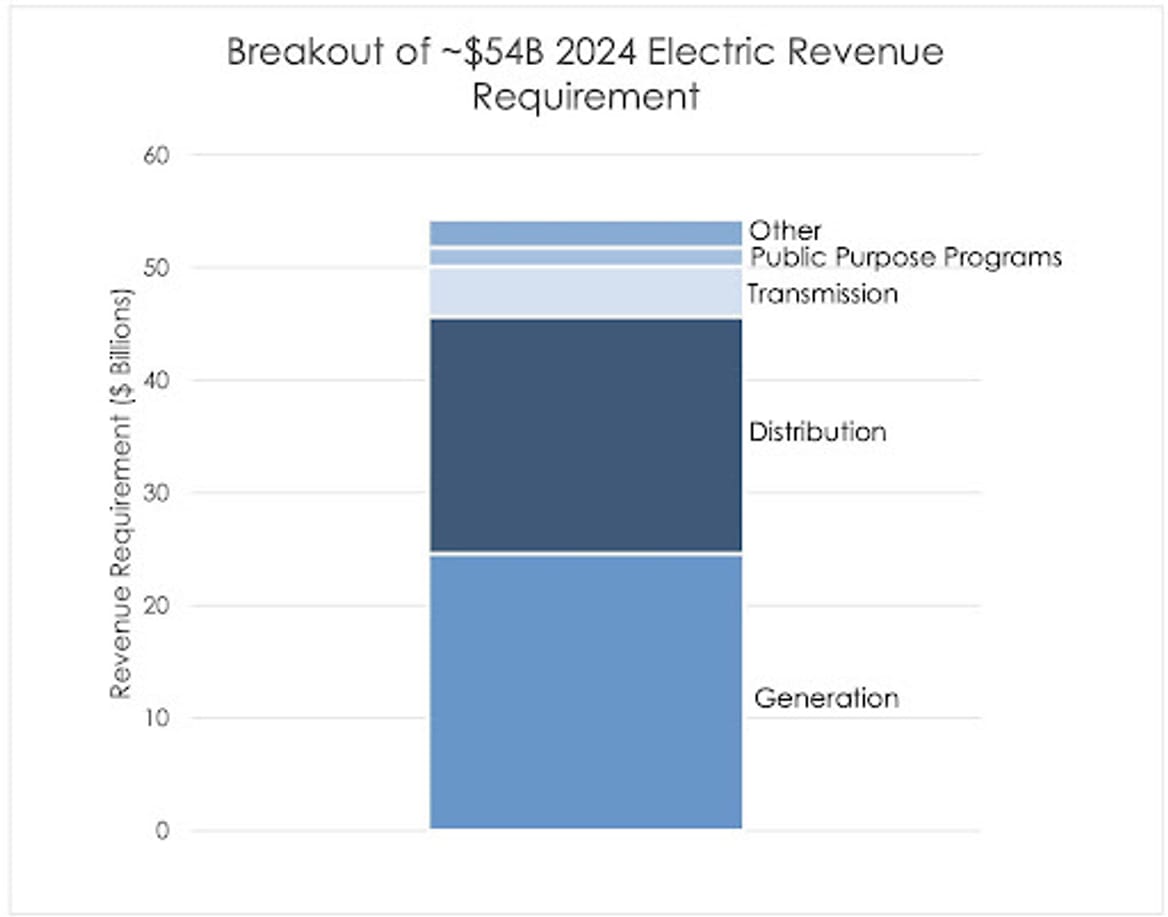

But Borenstein also said a majority of the rising utility costs over the past decade are tied to investments in low-voltage distribution grids and wildfire hardening and prevention.

“Those last two sort of meld together because we’re spending a whole lot of money on upgrading our distribution network, reinforcing our distribution network, in some cases, under-grounding it, in order to reduce wildfires,” he said.

The below chart from the CPUC’s February report highlights the majority of costs that come from paying for electricity generation and maintaining the utilities’ sprawling low-voltage distribution grids.

Borenstein agrees with the CPUC that rooftop solar incentives make up a significant portion of rising utility rates — a view that’s disputed by solar and environmental advocates. But even when the costs of net metering are calculated in the way that the CPUC proposes, they still make up a relatively small portion of typical residential utility customer bills compared to the “other” category that includes generation and grid costs, as the below chart from the Legislative Analyst’s Office report shows.

The Natural Resources Defense Council, one of the few environmental organizations that strongly favors reducing rooftop solar compensation, issued a report this week proposing a host of ways to reduce PG&E’s rates, including shifting those costs away from ratepayers. But NRDC also found that the “largest contributor to PG&E’s skyrocketing rates is the cost of vegetation management and hardening the grid to prevent wildfires,” making up more than half of the utility’s rate increases above the rate of inflation since 2018.

Going after those costs is tricky, however. When it comes to generation, utilities can’t back out of contracts for expensive power, even if they were signed more than a decade ago. Nor can they avoid buying power on the state’s energy markets during times when those prices spike.

Tackling grid costs puts regulators and lawmakers in a bind as well. Nobody wants utilities to skimp on critical investments like replacing aging equipment or protecting power lines from being knocked down by trees or high winds. Efforts to police utility grid investments risk forcing regulators and utilities to spend lots of time and effort delving into the minutiae of those plans without any clear promise of savings to show at the end of it.

Even so, Toney highlighted several bills being proposed this year, and others he hopes will be revived from last year’s session, that could drive down some of these costs.

On wildfire-related expenditures, he’d like to see a new bill that revives the policies proposed by SB 1003, a bill that failed to pass last year. The bill would have instructed the CPUC to limit utility wildfire spending outside of closely examined plans and put utility wildfire planning more squarely under the commission’s control.

Another option to address utility spending is AB 745, a bill that would increase state oversight of utility transmission grid upgrades. Energy analysts argue that a regulatory gap between federal and state authority over certain types of smaller grid projects has led to utility overspending on those projects. AB 745 cites a CPUC report that found $4.4 billion in transmission investments by California’s big utilities between 2020 and 2022, or nearly two-thirds of total grid spending, fell into this category.

California could also find other ways to pay for grid investments, Toney said. Those options can include securitization — having a utility issue bonds backed by the steady stream of payments its customers make on their bills — or the state issuing bonds to pay for certain utility costs. Both replace a portion of costs that are passed on to ratepayers, which “saves money because there’s no shareholder profit to be made,” he said.

SB 330, a bill proposed by state Sen. Steve Padilla (D), would authorize the state to “pilot projects to develop, finance, and operate electrical transmission infrastructure” via “low-cost public debt and alternative institutional models.” California will need to spend an estimated $45.8 billion to $63.2 billion on transmission by 2045, and an October report from the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force found that such public financing options could annually shave billions of dollars from rate increases in future years.

Some consumer advocates say lawmakers and regulators need to go after rising rates directly by limiting the return on investment that utilities are permitted to pass on to customers. Utility critics say that’s the most direct way to halt rate increases.

It’s also the most likely to trigger major pushback from utilities.

“We need to reduce the utilities’ profits to the national average or perhaps tie those profits to increases in safety,” Lynch proposed during February’s webinar. “As long as our policymakers focus on the wrong problem, we won’t find the right solution to reducing customers’ punishing and unwarranted bills.”

These efforts are hampered by the complexity and volume of data that goes into calculating such returns on investment as well as the fact that utilities control all the data. Indeed, utility critics have noted that recent rate-increase requests from PG&E have been approved by the CPUC in a perfunctory manner, with little to no attempt to order the utility to prove its cost increases were warranted.

Lynch blamed CPUC commissioners. ”It’s a fundamental failure of regulation, but it’s also a fundamental failure of political will to require the regulators to do their job as written in the law,” she said.

Utility finance expert Mark Ellis agreed that the CPUC needs to cut utilities’ profits. As an independent consultant and senior fellow at the American Economic Liberties Project, Ellis published a January paper accusing utilities of using financial legerdemain to justify excessive returns on their investments — and regulators of violating their duty to hold utilities to account.

The regulatory compact between states and investor-owned utilities boils down to this, he told Canary Media: “We’re going to give you a monopoly, but we won’t let you charge monopoly rents. Anything above your cost of capital is a monopoly rent.”

In an opinion piece in the San Francisco Chronicle, Ellis argued that California’s investor-owned utilities have been earning far above the cost of capital for decades — an assertion he backs up from experience working as former chief of corporate strategy and chief economist at Sempra, the holding company of Southern California Gas Co. and SDG&E.

The Energy Institute’s Borenstein agreed during his February presentation that utilities have “some important perverse incentives for capital investment” and that “cost of equity is the big point of contention because it’s hard to know what you need to pay stock shareholders to get them to invest.”

At the same time, “I don’t blame the CPUC for this,” he said. “I think the CPUC is massively understaffed and undercompensated, and they are just overwhelmed with the many things that they are required to do with limited staff. And when they get into these rate-of-return hearings, the utilities are able to bring world experts in finance.”

Ultimately, he said, “the CPUC is really outgunned and outmanned.”

Some lawmakers are going after utility profits more directly. SB 332, a bill sponsored by state Sen. Aisha Wahab (D), would cap investor-owned utility rate increases for residential customers to no more than the Consumer Price Index, a federal measure of cost-of-living inflation. It would also make shareholders rather than ratepayers provide more of the funding for the state’s utility wildfire fund — a sensitive issue amid rising investor uncertainty regarding SCE’s potential liability for January’s devastating Eaton Fire. SB 332 would also tie utility executive compensation to safety metrics.

“This bill flips the script and puts utility profits on the table,” said Roger Lin, a senior attorney at the nonprofit Center for Biological Diversity, which supports the legislation. While he conceded the proposal will face serious pushback from utilities, “we have to start looking at the systemic causes of the affordability crisis we have today in California.”

As Illinois looks to prepare its electric grid for the future, a new voluntary program in the Chicago area promises to lower costs for both customers and the utility system as a whole.

ComEd is finalizing plans to roll out time-of-use rates in 2026 following a four-year pilot program in which participants saved money and reduced peak demand between 6.5% and 9.7% each summer.

Under a plan before state utility regulators, customers who sign up would pay a much steeper energy-delivery charge during afternoon and early evening hours but see a significant discount overnight. The goal is to shift use to hours when the grid tends to be less congested as well as deliver cleaner and cheaper power.

“What we saw from the pilot was people did change their habits,” said Eric DeBellis, general counsel for the Citizens Utility Board, the state’s main utility watchdog.

Most standard customers are set to pay an energy-delivery charge of 5.9 cents per kilowatt-hour next year, while customers who enroll under ComEd’s proposed time-of-use program would pay a “super peak” delivery rate of 10.7 cents per kilowatt-hour between 1 p.m. and 7 p.m. but just 3 cents during overnight hours.

“The key to savings will be customers limiting usage from 1 pm to 7 pm,” John Leick, ComEd’s senior manager of retail rates, said in an email.

Under the proposal, most time-of-use rate customers would pay delivery rates of around 4 cents per kilowatt-hour during the morning, from 6 a.m. to 1 p.m., and in the evening between 7 p.m. and 9 p.m.

The details were approved in January by the Illinois Commerce Commission but put on hold last Thursday after commissioners agreed to consider a request by ComEd to also incorporate energy-supply charges into the program. (The initial proposal included only the portion of customers’ bills that pays for the delivery of energy but not the cost of electricity itself.)

The Citizens Utility Board is happy with the plan approved in January, DeBellis said, and it wants to ensure a delivery-only option remains for customers who buy power from alternative retail electric suppliers since these customers would not be able to participate in a supply-charge ComEd program. The utility watchdog also would have liked the “super peak” hours to be a bit shorter.

“For your typical upper-Midwest household, about half of their electricity is HVAC, and in the summer bills go up because of air conditioning,” DeBellis explained. “We were worried about the hours of super peak, the length of time we’re asking people to let the temperature drift up.”

The prospect of limiting air conditioning on hot afternoons could dissuade people from enrolling in the program, DeBellis continued. “Since each person’s subtle behavior changes are going to be small, it needs to be really popular to have an impact,” he said.

Consumer advocates have long asked for time-of-use rates, which are considered crucial as Illinois moves toward its goal of 1 million electric vehicles by 2030. If too many EVs charge during high energy-demand times, the grid could be in trouble.

“We want EVs to be good for the grid, not bad,” said DeBellis.

People with electric vehicles will save an extra $2 on their monthly energy bill per vehicle just by enrolling in the proposed ComEd time-of-use program, with a cap of two vehicles for up to two years.

“This will help incentivize customers with EV’s to sign up and pay attention to the rate design and hopefully charge in the overnight or lower priced periods,” said Leick.

Richard McCann, a consultant who testified before regulators on behalf of the Citizens Utility Board and the Environmental Defense Fund, recommended that in order to qualify for rebates for level 2 chargers, customers must participate in the new time-of-use program or other programs related to when electricity is used.

DeBellis and his wife recently bought an EV, and he thinks time-of-use prices could be an extra incentive for others to follow suit. However, he thinks dealers and buyers are more focused on EVs “being cool” and tax incentives toward the lease or purchase price, rather than fuel savings.

“I don’t have the impression people trying to buy a car are doing the math and thinking about how much they would save on fuel” with an EV, he said. “Time-variant pricing makes those savings even more, but the math is kind of impenetrable for most people. In my humble opinion, fuel savings should be a way bigger factor, and time-of-use rates should be part of it.”

ComEd crafted the time-of-use program after a four-year pilot and a public comment process overseen by state regulators. The pilot was focused on the energy supply part of the bill, but DeBellis noted that the lessons apply to any time-of-use program, since demand peaks are the same regardless of which part of the bill one looks at.

The pilot program’s final annual report showed that both EV owners and people who did not own EVs significantly reduced energy use during “super peak” hours in the summer. Even though participants without EVs did little load-shifting during the non-summer seasons, they still saved an average of $6 per month during the last eight months of the pilot because of the way electricity was priced in the program. EV owners saved significantly more, with most cutting bills by $10 to $30 per month and some saving over $70 per month from October 2023 to May 2024.

Overall, in the pilot’s final year, energy usage did shift significantly from peak hours to night-time hours thanks to an increasing number of EV owners participating in the program.

In 2021 and 2022, participants in the pilot faced high peak-time energy rates because of market fluctuations. Some customers dropped out for this reason, Leick said, but participation remained near the cap of 1,900 residents during the pilot, with over a quarter of them being EV owners by the end.

Many utilities around the country already offer time-of-use programs: 42% of 829 utilities responding to a federal survey have such rates, according to McCann’s testimony.

ComEd’s filings with state regulators include a survey of 15 time-of-use rates established by seven other large utilities nationwide. The study found that in the first year of ComEd’s pilot program, the utility had a larger proportional difference between peak and off-peak pricing than most of the rates studied. (ComEd’s peak and off-peak rates, however, were lower than most of the others, so the total price difference was larger for other utilities.)

ComEd also saw larger reduction in summer peak-time electricity demand than many of the other time-of-use rates. ComEd’s program structure was similar to that of the other utilities, the company doing the study found, though in California, peak times were later in the afternoon, likely because of the state’s climate and proliferation of solar energy.

The program is designed to be revenue-neutral, meaning ComEd won’t earn more or less depending on when people use energy. Still, it has potential to lower costs to the system overall by helping to make more efficient use of existing infrastructure and postponing the need for new generation or transmission investments.

The new time-of-use rate would only apply only to residents. Industrial and commercial customers already have an incentive to use power at night, since their energy-delivery charge is based on their highest 30-minute spike between 9 a.m. and 6 p.m. on weekdays. If a business’ most intense energy use is after 6 p.m. or on weekends, their bill will be lower than if that same spike happened during usual business hours, Leick explained. Commercial and industrial customers’ energy-supply rates, meanwhile, are based on hourly market prices, which are typically higher during peak times.

ComEd has since 2007 offered a voluntary real-time pricing program that lets people save money if they use energy when system demand and hence market prices are lower. But keeping tabs on the market is beyond what most customers other than “energy wonks” are willing to do, DeBellis noted. Only about 1% of residential customers have enrolled in the real-time pricing program since it started, according to McCann’s testimony.

“Real-time pricing was so complicated it was basically gambling,” DeBellis said. “We’re very happy to have a time-based rate offering that’s very predictable, where people can be rewarded for establishing good habits.”

Some clean-energy groups had argued for a program that automatically enrolls residents unless they opted out. DeBellis said the Citizens Utility Board promoted the opt-in version that is currently proposed.

“We want people on this program to be aware they’re on the program, otherwise you won’t get behavior change. You’re just throwing money at random variation,” DeBellis said.

The Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act, introduced into the state legislature in February and backed by a coalition of advocacy groups, would mandate large utilities offer residential time-of-use rates, outlining a structure similar to what ComEd is planning. After the rates have been in place for a year, the Illinois Commerce Commission could do a study to see if the rates are indeed reducing fossil-fuel use and work with utilities to adjust if needed.

While the commission’s ruling last week reopens debate about the program’s structure, a ComEd spokesperson said the company is confident it will be available by next year.

For most U.S. homes, heat pumps are a no-brainer: They can lower energy bills and eventually pay for themselves all while slashing carbon emissions. But the economics don’t work in favor of heat pumps for every home — and particularly not for those in states that have high electricity prices relative to those of fossil gas.

Adjusting the structure of customer electricity rates could turn the tables, according to a report out today from the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE.

The ratio of average electricity prices to gas prices (both measured in dollars per kilowatt-hour) is known as the “spark gap” — and it’s one of the biggest hurdles to nationwide electrification. A heat pump that is two to three times as efficient as a gas furnace can cancel out a spark gap of two to three, ensuring energy bills don’t rise with the switch to electric heat. But in some states, the gulf is so big that heat pumps can’t close it under the existing rate structures.

Worse, heat pump performance can decrease significantly when it’s extremely cold (like below 5 degrees Fahrenheit), so without incentives, the economic case is harder in states with both harsh winters and electricity that’s much more expensive than gas, like Connecticut and Minnesota. In these places, heat pump adoption is “hit by double whammy,” said Matt Malinowski, ACEEE buildings director.

The weather might be hard to change, but the spark gap is malleable: Utilities, regulators, and policymakers can shape electricity rates. By modeling rates for four large utilities in different cold-climate states, ACEEE found that particular structures can keep energy bills from rising for residents who switch to heat pumps, without causing others’ bills to go up.

Flat electricity rates are a common practice. They’re also the worst structure for heat pumps, Malinowski said.

When utilities charge the same per-kilowatt-hour rates at all hours of the day, they ignore the fact that it costs more to produce and deliver electricity during certain hours. That’s because, like a water pipe, the power grid needs to be sized for the maximum flow of electrons — even if that peak is brief. Meeting it requires the construction and operation of expensive grid infrastructure.

Flat rates spread the cost of these peaks evenly across the day rather than charging customers more during the high-demand hours that cause a disproportionate amount of grid costs.

But heat pumps aren’t typically driving peak demand — at least, not for now while their numbers are low. Demand usually maxes out in the afternoon to evening, when people arrive home from work, cook, do laundry, and watch TV. Households with heat pumps actually use more of their electricity during off-peak hours, like just before dawn when it’s coldest, than customers with gas, oil, or propane heaters.

Heat pumps “provide the utility a lot of revenue, and they do that at a time when there isn’t that much electricity consumption,” Malinowski said.

Under a flat-rate design, cold-climate heat pump owners “are basically overpaying,” he added. “Adjusting the rates to better reflect their load on the system — and the benefits to the system that they provide — is only fair.”

A rate design that bases charges on when electricity is used would help course-correct. Known as “time-of-use,” this structure charges more for power consumed during periods of peak demand and less for power consumed at other times, or “off-peak,” coinciding with heat pumps’ prime time.

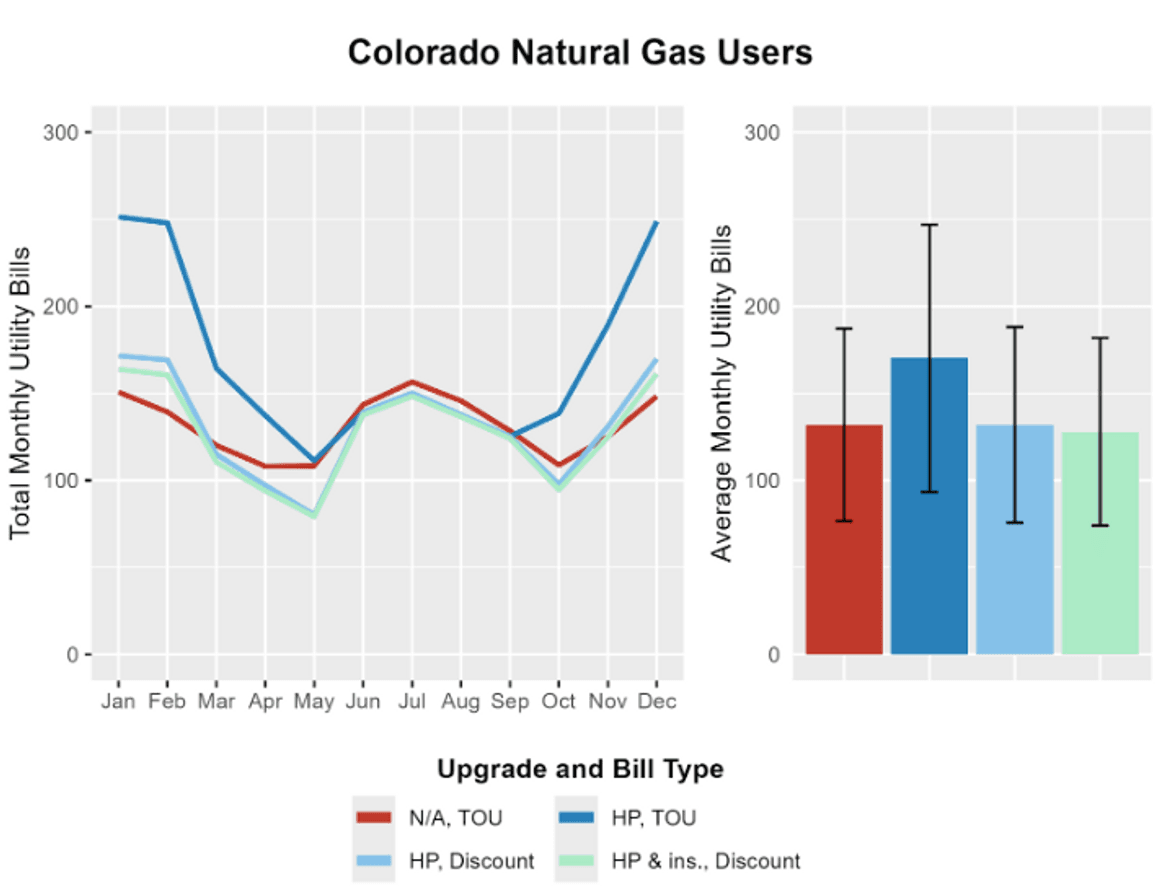

Utility ComEd serving the Chicago area is working to finalize time-of-use rates for households, joining the ranks of several other U.S. providers that already offer this structure, like Xcel Energy in Colorado, Pacific Gas and Electric in California, and Eversource in Connecticut.

Demand-based rates are another way of accounting for a customer’s peak demand profile and can help reduce a heat pump owner’s energy bills. This approach tacks on fees scaled to a customer’s peak demand that month. If it’s 3 kilowatts, and the demand charge is $10 per kilowatt, the fee will be $30. But importantly, this structure also lowers the rates charged for the total volume of electricity.

Even though households switching from gas to heat pumps under such a program would see higher charges for peak demand than before, Malinowski said “they’ll be using so much more electricity overall that they end up benefiting much more from that lower volumetric [per-kilowatt-hour] charge.” As a result, their energy bills can be lower than with a flat-rate program, the report finds.

Winter discounts also help heat pumps make financial sense. In most states, electricity usage waxes in the summer — when people blast their air conditioners — and wanes in the winter, when many residents switch to fossil-fuel heating.

Some utilities offer reduced electricity prices in winter to drum up business, a structure that benefits households who heat their homes with electrons. Xcel in Minnesota drops its June-through-September summer rate of 13 cents per kilowatt-hour to 11 cents per kilowatt-hour during the rest of the year for all customers. For those with electric space heating, including heat pumps, the rate is lower still: 8 cents per kilowatt-hour — a discount of 39% from the summer rate.

According to ACEEE’s modeling, the winter discount alone can save Minnesota Xcel customers in single-family homes on average more than $350 annually once they swap a gas furnace for a heat pump. Combining the winter discount with existing time-of-use rates or simulated demand-charge rates (given in the study) can further reduce annual bills by another $70.

In Colorado, another state ACEEE analyzed, Xcel provides both time-of-use rates and a much shallower winter discount of about 10%. Even taken together these structures aren’t enough to close the spark gap for heat pumps. Pairing that discount with demand-based rates wouldn’t do the trick either, the team found. Only when they used the much steeper discount that Xcel deploys in Minnesota were they able to keep customers’ modeled heating bills from climbing when they switched to heat pumps.

One more option for utilities and regulators: discounts specifically for customers with heat pumps. More than 80 utilities in the U.S. currently offer discounted electric heating rates, with 12 providing them specifically for households with heat pumps, according to a February roundup by climate think tank RMI.

Massachusetts regulators approved a plan by utility Unitil last June to offer a wintertime heat-pump discount — the first in the state — and directed National Grid to develop one, too. Unitil’s discount amounts to at least 20% off the regular per-kilowatt-hour rate, depending on the plan customers choose. Colorado policymakers are also requiring investor-owned utilities to propose heat pump rates by August 2027.

The takeaway from ACEEE’s results is that in some states, the above rate designs could be promising avenues to ensure switching to heat pumps doesn’t raise energy bills for most single-family households.

But in other cases, additional policy might be needed. Connecticut’s electricity prices are so high that these rate structures weren’t enough to close the spark gap, the authors found. They recommend policymakers consider broader changes like putting a price on carbon emissions, implementing clean-heat standards that require utilities to take steps toward decarbonized heating, or investing in grid maintenance and upgrades to make electricity more affordable — for all customers.

Last May, Florida enacted a law deleting any reference to climate change from most of its state policies, a move Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis described as “restoring sanity in our approach to energy and rejecting the agenda of the radical green zealots.”

That hasn’t stopped the Sunshine State from becoming a national leader in solar power.

In a first, Florida vaulted past California last year in terms of new utility-scale solar capacity plugged into its grid. It built 3 gigawatts of large-scale solar in 2024, making it second only to Texas. And in the residential solar sector, Florida continued its longtime leadership streak. The state has ranked No. 2 behind California for the most rooftop panels installed each year from 2019 through 2024, according to data the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie shared with Canary Media.

“We do expect Florida to continue as No. 2 in 2025,” said Zoë Gaston, Wood Mackenzie’s principal U.S. distributed solar analyst.

Florida is expected to again be neck and neck with California for this year’s second-place spot in utility-scale solar installations, said Sylvia Leyva Martinez, Wood Mackenzie’s principal utility-scale solar analyst for North America.

Overall, the state receives about 8% of its electricity from solar, according to Solar Energy Industries Association data. The vast majority of its power comes from fossil gas.

The state’s solar surge is the result of weather — both good and bad — and policies at the state and federal level that have made panels cheaper and easier to build, advocates say.

“Obviously in Florida, sunshine is extremely abundant,” said Zachary Colletti, the executive director of the Florida chapter of Conservatives for Clean Energy. “We’ve got plenty of it.”

The state is also facing a growing number of extreme storms. Of the 94 billion-dollar weather disasters that federal data show unfolded in Florida since 1980, 34 occurred in the last five years.

“Floridians have long understood that not only is solar good for your pocket, it’s also good for your home resilience,” said Yoca Arditi-Rocha, the executive director of The CLEO Institute, a Miami-based nonprofit that advocates for climate action. “In the face of increasing extreme weather events, having access to reliable energy is a big motivator.”

The tax credits available under former President Joe Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act have also made buying panels cheaper than ever before, she said.

“A lot of people took advantage of that. I’m one of them,” Arditi-Rocha said. “As soon as I saw that the federal government was going to give me 30% back on my taxes, I decided to make the investment and got myself a solar system that I could pay back in seven years. It was a win-win proposition.”

But solar started growing in Florida long before Democrats passed the IRA in 2022, and that’s thanks to favorable state policies.

Municipalities and counties have little say over power plants, giving the Florida Public Service Commission ultimate control over siting and permitting. Plus, solar plants with a capacity under 75 megawatts are exempt from review and permitting altogether under the Florida Power Plant Siting Act.

The latter policy in particular has made building solar farms easy and inexpensive for the state’s major utilities, said Leyva Martinez. Companies such as NextEra Energy–owned Florida Power & Light, the state’s largest electrical utility, have for years patched together gigawatts of solar with small farms.

“We’re seeing this wave of project installations at gigawatt scales, but if you look at what’s actually being built, it’s a small 74-megawatt [project] here or 74.9-megawatt project there,” she said. “It’s just easier to permit in the state, and developers have realized that they can keep installations at this range and they don’t need to go through the longer process.”

The solar buildout has prompted some backlash in rural parts of the state. A bill Republican state Sen. Keith Truenow filed last month proposes granting some additional local control over siting and permitting solar farms on agricultural land.

“You’re starting to see a lot more complaining about the abundance of solar installations in more rural areas,” Colletti said. The legislation, he said, “would add some hurdles and ultimately add costs” but “wouldn’t necessarily reverse the state’s preemption” of local permitting authorities.

NextEra and Florida Power & Light did not respond to an email requesting comment. Nor did Truenow return a call.

While the bill is currently making its way through the Legislature, DeSantis previously vetoed legislation that threatened Florida’s solar buildout.

In 2022, the governor blocked a utility-backed bill to end the state’s net metering program, which pays homeowners with rooftop solar for sending extra electricity back to the grid during the day.

“The governor did the right thing by vetoing that bill that would have strangled net metering and a lot of the rooftop solar industry in Florida,” Colletti said. “I know Floridians are much better off for it because we are able to offset our costs very well and take more control and ownership over our households.”

A telephone survey conducted by the pollster Mason-Dixon in February 2022 found that among 625 registered Florida voters, 84% supported net metering, including 76% of self-identified Republicans.

“It’s not about left or right,” Arditi-Rocha said. “It’s about making sure we live up to our state’s name. In the Sunshine State, the future can be really sunny and bright if we continue to harness the power of the sun.”

As winter turns to spring, Texas is setting new records with its nation-leading clean energy fleet.

In just the first week of March, the ERCOT power grid that supplies nearly all of Texas set records for most wind production (28,470 megawatts), most solar production (24,818 megawatts), and greatest battery discharge (4,833 megawatts). Only two years ago, the most that batteries had ever injected into the ERCOT grid at once was 766 megawatts. Now the battery fleet is providing nearly as much instantaneous power as Texas nuclear power plants, which contribute around 5,000 megawatts.

“These records, along with the generator interconnection queue, point towards a cleaner and more dynamic future for ERCOT,” said Joshua Rhodes, a research scientist studying the energy system at The University of Texas at Austin.

The famously developer-friendly Lone Star State has struggled to add new gas power plants lately, even after offering up billions of taxpayer dollars for a dedicated loan program to private gas developers. Solar and battery additions since last March average about 1 gigawatt per month, based on ERCOT’s figures, Texas energy analyst Doug Lewin said. In 2024, Texas produced almost twice as much wind and solar electricity as California.

When weather conditions align, the state’s abundant clean-energy resources come alive — and those conditions aligned last week amid sunny, windy, warm weather. On March 2 at 2:40 p.m. CST, renewables collectively met a record 76% of ERCOT demand.

Then, on Wednesday evening, solar production started to dip with the setting sun. More than 23,000 megawatts of thermal power plants were missing in action. Most of those were offline for scheduled repairs, but ERCOT data show that nearly half of all recent outages have been “forced,” meaning unscheduled.

At 6:15 p.m. CST, batteries jumped in and delivered more than 10% of ERCOT’s electricity demand — the first time they’ve ever crossed that threshold in the state.

“Batteries just don’t need the kind of maintenance windows that thermal plants do,” said Lewin, who authors the Texas Energy and Power newsletter. “The fleet of thermal plants is pretty rickety and old at this point, so having the batteries on there, it’s not just a summertime thing or winter morning peak, they can bail us out in the spring, too.”

At some level, the March records show clean energy excelling in the conditions that are most favorable to it. Bright sun and strong winds boosted renewable generation, while temperate weather kept demand lower than it would be on a hot summer or a cold winter day. But those seemingly balmy circumstances could belie a deeper threat to the Texas energy system.

“One thing that I don’t think is talked about nearly enough is the potential for problems in shoulder season,” said Lewin.

If unusually hot weather struck during a spring day with lots of gas and coal power plants offline, ERCOT could struggle to meet demand, even if it was much lower than the blistering summer peaks. In fact, this happened in April 2006, when a surprise heat wave forced rolling outages, Lewin noted. Texas officials don’t talk much about climate change, but that kind of hot weather in the springtime is becoming more common.

Last summer produced ample data on how the surge in solar and battery capacity reduced the threat to the grid from heat waves and lowered energy prices for customers. This spring, batteries and renewables are showing they can also fill in the gaps when traditional plants step back.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the week” column.

Last year was fantastic for battery storage. This year is poised to be even better.

The U.S. is set to plug over 18 gigawatts of new utility-scale energy storage capacity into the grid in 2025, up from 2024’s record-setting total of almost 11 GW, per Energy Information Administration data analyzed by Cleanview. Should that expectation bear out, the U.S. will have installed more grid batteries this year alone than it had installed altogether as of 2023.

The U.S. grid battery sector has been on a tear in recent years — and California and Texas are the reasons why. Combined, the two states have installed nearly three-quarters of the country’s total energy storage capacity of over 26 GW.

California has long held the top spot on large-scale battery storage installations. Even last year, when the EIA forecast that Texas would claim the lead, California held on by a few hundred megawatts. This year EIA again expects Texas to outpace California, only now by an even wider margin than last year. The Lone Star State could build nearly 7 GW of utility-scale storage in 2025 compared to California’s 4.2 GW.

But the new state-level storyline to watch is the rise of Arizona. The state built just under 1 GW of storage in 2024, buoyed by massive new projects like the Sonoran Solar Energy Center and the Eleven Mile Solar Center that pair solar with batteries to soak up as much desert sun as possible. This year, EIA says Arizona is on track to nearly quadruple last year’s total and build 3.6 GW of storage.

It’s worth noting that EIA’s 2024 storage forecast overshot actual installations by about 3 GW — and developers didn’t have the Trump administration to contend with then. President Donald Trump has not outright targeted energy storage, but the uncertainty surrounding the future of clean energy tax credits could have a chilling effect on investment, as it has had on projects in adjacent sectors like solar and battery manufacturing.

Despite the political chaos, developers are barrelling ahead. Just over 12 GW of storage projects are either under construction or complete and waiting to plug into the grid. And, as Cleanview points out, the crucial tax credit for battery storage projects is already locked into the tax code for 2025, giving developers some measure of certainty — at least for the months ahead.

Two years after slashing compensation for rooftop solar owners who send power back to the grid, California policymakers are once again looking for ways to contain high and rising electricity rates — which means the accusation that rooftop solar pushes costs onto other utility customers is once again rearing its head.

Last month, representatives of the California Public Utilities Commission testified in a state legislative hearing that California’s system for compensating owners of rooftop solar is a primary cause of the state’s rapidly rising utility rates.

That testimony is backed by a CPUC report, issued last month in response to an October order from Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom to find ways to reduce utility-rate increases. Among other potential cost savings, the report proposes further reductions to rooftop solar compensation that the CPUC has already cut for homes, businesses, farms, and schools in the past two years.

The CPUC’s rationale is that solar programs shift costs onto customers who don’t have solar. Linda Serizawa, director of the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office, which is tasked with protecting utility customers, told lawmakers that the state’s rooftop solar regime has led to non-solar-equipped customers of Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas & Electric paying $8.5 billion more than they otherwise would have in 2024. That increase accounts for up to a quarter of those customers’ monthly bills, on average, according to the Public Advocates Office.

Solar advocates and environmental justice groups have long said this “cost-shift” argument is false. In fact, they say, California utility customers would be paying even higher electric rates if the state hadn’t launched policies back in 2006 that have incentivized California homes, businesses, schools, and other utility customers to install more than 2 million rooftop solar systems since then.

Last week, several pro-solar groups shared new analysis, expanding on research released last year by energy and environmental consulting firm M.Cubed Consulting.

The latest round in the “cost-shift” debate comes as the CPUC’s December 2022 decision to cut compensation for newly installed rooftop solar systems has decimated the country’s leading rooftop solar market, potentially putting the state’s carbon-cutting goals out of reach. About 45% of the state’s solar power now comes from rooftop and distributed sources rather than utility-scale projects, but new rooftop solar installations have fallen dramatically since the CPUC’s new compensation system went into effect in mid-2023.

Without more rooftop solar, “we’re going to have increasing electricity costs, and we’re going to fall short of our clean energy goals,” said Ken Cook, president of the nonprofit Environmental Working Group. The challenge, he said, is to agree on regulatory structures that allow the state to “harness rooftop solar and distributed energy to solve both of these problems.”

But the cost-shift argument has short-circuited that kind of policy discussion, said Brad Heavner, policy director for the California Solar and Storage Association, a solar-industry trade group that funded M.Cubed’s cost-shift analyses. “It was devised by the utilities as a way to reframe what rooftop solar is and to put a negative light on it. And it has worked.”

Now, with mounting pressure to reduce utility rates, rooftop solar advocates fear the argument will be used once again to justify further cuts to an industry they view as crucial not only to climate goals but as a net benefit — not cost — to utility customers.

The cost-shift argument was initially put forward by the Edison Electric Institute, a trade group representing U.S. electric utilities. Utilities pay for building and maintaining the power grid through the rates they charge customers. The cost-shift thesis argues that paying some customers for their rooftop solar power unfairly shifts the burden of covering the costs of keeping utilities running onto other customers.

But Richard McCann, a founding partner at M.Cubed, argues that California’s nation-leading rooftop solar resource has saved customers as much as $1.5 billion in 2024 through savings accrued over the past two decades. The reason, in his view, is simple: More rooftop solar means utilities need to buy less energy from other resources and build less power lines and other grid infrastructure to meet customers’ power demand.

Back in 2005, the California Energy Commission forecasted that the state’s peak demand for electricity — the primary driver of utility costs for generation and grid capacity that are passed on to customers — would grow from about 45 gigawatts to more than 60 GW by 2022 or so, McCann said.

But peak electricity demand on the statewide grid operated by the California Independent System Operator (CAISO) has grown far more slowly. The system has instead topped out at a record-setting peak of 52 GW in September 2022 — only about 2 GW over the previous record set in 2006.

Over that same time, the state’s net-metering policies have incentivized millions of customers of the state’s three big utilities to install solar panels, he said. Much of the state’s peak grid demand coincides with hot summer afternoons — the same time that rooftop solar produces the most electricity.

CAISO does not directly track how much power rooftop solar generates across millions of California homes and businesses, McCann noted. But the simultaneous trends of lower-than-forecasted peak demand and growing rooftop solar resource indicate that “rooftop solar has displaced the peak load demand in the CAISO system and kept the CAISO load flat over that same time period,” he argued.

If that’s the case, customers investing in rooftop solar have helped the state’s utilities avoid investing in new generation, transmission, and distribution, potentially saving ratepayers billions of dollars, he said. “Rates would be even higher than what they are now if rooftop solar had not been present.”

McCann’s view, supported by most environmental advocates, the solar industry, and some energy analysts, is hotly contested by utilities as well as independent analysts who have championed the cost-shift thesis.

In the latter group’s view, rooftop solar is a more expensive and less efficient alternative to building utility-scale solar power plants and transmission grids. Shifting money from those larger-scale alternatives not only pulls money from customers without solar to those with solar, they argue, but represents a lost opportunity for utilities to invest in more cost-effective clean power.

Severin Borenstein, head of the Energy Institute at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, is a key proponent of the cost-shift theory. In January, Borenstein published a paper challenging McCann’s take on the value of rooftop solar, citing “fundamental conceptual errors that undermine most of its points.”

Borenstein said that a proper analysis finds that in 2024 solar net-metering pushed about $4 billion in costs onto utility customers who don’t have solar. That’s not nearly as high as the $8.5 billion figure from the CPUC’s Public Advocates Office, but it’s still a net cost rather than a benefit to customers at large.

In February, McCann published a reply to Borenstein’s critique, delving into his point-by-point differences of opinion on how these costs should be calculated. Much of the dispute is highly technical in nature. And because these analyses rely on heavily varied assumptions — including what would have happened if the past 20 years of rooftop solar policy hadn’t played out the way they have — many of the conflicts between the two sides on precise numbers can’t be answered definitively.

That uncertainty has led both sides to accuse the other of using intentionally misleading data and methods. McCann acknowledged that his initial analysis last year miscalculated the benefits that he believes rooftop solar has delivered to customers of the state’s three big utilities. He originally calculated $2.3 billion worth of benefits in 2024, rather than the $1.5 billion that emerged from his latest analysis.

The in-the-weeds exchange between McCann and Borenstein reveals a deeper disagreement at the heart of their vastly different estimates — one that cost-shift foes say California regulators have failed to fully acknowledge. It centers on a simple question: When a household generates solar power at the same time as it’s using electricity from the grid, who owns that solar?

According to McCann, who cited legal precedents and the fundamental physics that determine the flow of electrons, solar power that customers generate and consume at their own homes and buildings is theirs by right. They paid for the solar systems, and they’re directly using the electricity those systems generate.

But according to both Borenstein and the Public Advocates Office’s analysis, solar power simultaneously generated at the time that power is being consumed on site should be considered as a cost to other utility customers.

As Borenstein states in his January rebuttal, “So long as a solar system is connected to the grid, there is no real distinction between self-consumption and grid supply. Despite this fact, if a customer’s aggregate rooftop solar production during an hour is equal to the household’s consumption, then some argue that the customer is ‘self-consuming’ and their consumption in that hour should not be obligated to make any contribution to grid costs or other costs that are part of the retail price.”

In other words, according to this logic, allowing solar-equipped customers to count the power they generate as offsetting their use of grid power undermines the fundamental structure of utility rates, which recover the costs of electricity delivery by charging customers for their hour-by-hour energy use.

These two different interpretations go a long way in explaining the chasm between McCann’s analysis and those from Borenstein and the Public Advocates Office. According to McCann’s analysis, this category of “cost” — self-generated solar power considered as the property of the utility and ratepayers at large, rather than belonging to the individual households using it — accounts for nearly $4 billion of the Public Advocates Office’s $8.5 billion cost-shift calculation.

But McCann believes that Borenstein and the Public Advocates Office’s perspective runs afoul of standing legal and regulatory precedent on such matters.

He cited a 2015 paper in which Jon Wellinghoff, former chairman of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, and Steven Weissman, a former CPUC administrative law judge and a founder of the energy law program at the UC Berkeley School of Law, state that “[p]roperty owners in the United States have the right to generate electricity onsite, for their own use. This understanding is so fundamental that legislatures have not bothered to spell it out.”

FERC has dismissed arguments that solar generated at homes and other buildings should be regulated by the federal authorities governing the bulk-electricity grid.

The bigger problem with the cost-shift numbers from CPUC and the Public Advocates Office is that they have never been subjected to the kind of regulatory process that could allow regulators, lawmakers, and the public at large to fully grasp and argue over the validity of the assumptions that have gone into them, Loretta Lynch, an attorney and energy policy expert who served as CPUC president from 2000 to 2002, said during a webinar led by M.Cubed last week.

Instead, the Public Advocates Office published a paper in August 2024 asserting its cost-shift figure, which has since been used to justify a range of policy decisions, she said. That’s not how regulators are supposed to do things, Lynch added.

“Before the CPUC goes and touts an unvetted report of dubious calculation and worth, perhaps it should put that report in an evidentiary hearing in a proceeding, along with Richard’s analysis,” she said, referencing M.Cubed’s latest paper.

Then, the CPUC could “have the expert analysts go toe-to-toe, under oath, with questions and cross-examination, so we can see the assumptions made, the data used, and whether or not the conclusions are valid.”

It’s important to note that these cost-shift analyses are looking at California’s rooftop solar past, not its future. In more recent years, as solar has grown to make up an increasing portion of California’s electricity-generation mix, peak grid demands have shifted from late afternoons when the sun is still shining to hot evenings after the sun goes down. Every new increment of solar power added to the grid is less and less useful on its own in reducing these new “net peak” demands.

Batteries that store power for use during these post-sundown peaks have thus become a vital addition to new solar installations, both at the utility scale and at homes and businesses.

The net-billing tariff the CPUC approved in late 2022 to replace its previous net-metering regime offers far lower payments for the electricity that newly installed rooftop solar systems inject onto the grid, except for a few hours per year when peak power is in dire need. That structure rewards customers who add batteries that can store and inject power during those valuable hours — a service that should reduce how much energy utilities need to secure and how much grid infrastructure they need to build to serve those peak moments.

But solar advocates are now worried that the CPUC’s report on containing rate increases calls for reducing the value of solar power for “legacy” net-metering customers as well.

Under the CPUC’s previous net-metering regimes, customers are paid full retail rates for solar power they send back to the grid for 20 years. In its February report, the CPUC proposes shortening those legacy periods, which could reduce costs for utilities but also undermine the economic calculations that made rooftop solar worthwhile to customers who installed it with the assumption that those rules wouldn’t change.

The CPUC report also proposes adding a “grid-benefits charge” to the bills of existing rooftop solar owners — in essence, charging them extra for having solar panels. Utilities have previously proposed this concept and shortening legacy net-metering periods, but regulators rejected them after significant pushback.

The CPUC’s new report doesn’t advocate for these or any other particular changes to utility regulations or policy. But it does propose that state lawmakers consider finding “non-ratepayer sources” to compensate customers with rooftop solar.

The CPUC didn’t specify which alternative sources could fill that gap. Prior proposals to use state tax revenues or California’s cap-and-trade program could be part of the mix, said Mark Toney, executive director of The Utility Reform Network, a ratepayer-advocacy group.

But even supporters of those concepts like Toney don’t see much hope of lawmakers fielding bills that would ask taxpayers to shoulder costs now borne by utilities. “It is wishful thinking that we could shift rooftop subsidies to taxpayers,” he said. “I’m not holding my breath here.”

Given the unlikely prospects of using taxpayer funds to pay rooftop solar customers, solar advocates fear that the CPUC’s proposal is an opening shot in a battle to weaken rooftop solar even further.

Cook of the Environmental Working Group described the potential ramifications of such a move: “If people come to believe that any agreement they thought was going to be good for, say, 20 years means nothing to the state and to the utility regulators — if it can be wiped away — that’s going to make it even harder to convince people to think that their own investments and rooftop solar are going to pencil out.”

Ascend Elements, a leading contender in advanced battery recycling, canceled a portion of its planned battery-materials plant last week. The company still aspires to expand a fully domestic battery supply chain but has had to adapt to tumultuous policy and market conditions.

China controls most of the world’s processing capacity for key battery inputs. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. began a concerted effort to build up those resources — like lithium mines, lithium-processing plants, and advanced facilities that make cathode active materials (CAM) that go into batteries.

A cohort of battery-recycling startups joined the cause, pledging to safely and economically disassemble old batteries and funnel their pieces back into the supply chain. Ascend is one of them: The Massachusetts-based company opened a plant in Covington, Georgia, in March 2023 that grinds up used batteries into the powder known as black mass. Ascend is currently building a plant in Hopkinsville, Kentucky, where it will refine that black mass into battery materials.

That project, called Apex 1, is still happening, but Ascend has narrowed its scope: The startup announced last week that it is scrapping plans to produce CAM there and agreed to cancel the $164 million grant that the project won from the Department of Energy. Ascend intends to convert the space that would have made CAM into a lithium carbonate production line, using a proprietary technology the company rolled out at its Covington plant early this year.

Apex 1 will still produce the precursors to CAM known as pCAM, an effort aided by a separate $316 million grant from the DOE. These powders include cathode materials like nickel, manganese, and cobalt; manufacturers add lithium to those ingredients and fine-tune the recipe to generate finished CAM.

Between the previously planned pCAM and the newly announced lithium carbonate lines, Ascend still plans to invest about $1 billion in the Kentucky project, spokesperson Thomas Frey told Canary Media on Tuesday.

The companies that buy CAM already have supplies lined up, and demand isn’t growing fast in the near-term, Frey said. But the companies that make that CAM need to obtain the precursor materials from somewhere, and that’s where Ascend still sees an opportunity.

“By getting out of CAM, we’re essentially turning potential competitors into potential customers,” he said.

Ascend can sell its pCAM to specialized CAM manufacturers or to electric-vehicle and battery manufacturers who want their suppliers to use that particular material, Frey noted.

“We’re still really highly committed to creating a domestic, closed-loop battery ecosystem in the U.S.,” Frey said. “We will be the only large-scale manufacturer of pCAM in America. With tariffs at play and things like that, that makes us pretty appealing.”

Another benefit to focusing on pCAM is that it’s a more generalizable product than CAM, which has to be tailored intricately to each battery manufacturer’s proprietary designs. Since batteries are such a precisely calibrated technology, prospective buyers scrutinize CAM samples for a year or more before clearing producers for a large commercial order. The sales cycle for pCAM is quicker and easier, Frey said.

Ascend’s timeline has also been influenced by a broader slowdown in the U.S. electric-vehicle manufacturing buildout. Detroit automakers have pulled back on their earlier enthusiasm for EV production, which has pushed back timelines for the battery supply chain, including CAM and pCAM.

Some companies have canceled battery factories in just the last few weeks, like Freyr Battery (now T1 Energy), which had aspired to build one in Georgia, and U.S. startup Kore Power, which ditched plans for a facility near Phoenix.

Ascend has extended its timeline for Apex 1 from the end of 2025 to the third quarter of 2026, which Frey said allows for a more cost-effective construction process. Commissioning is underway for the new lithium carbonate line at Ascend’s Covington factory, which should begin commercial production in the next few months, he added.

The Covington plant has also struggled with a more fundamental problem: The old batteries the facility grinds up keep catching fire.

Firefighters responded to a Feb. 20 conflagration in a tractor trailer delivering used batteries to the site. The fire consumed the trailer but did not jump to the adjacent building, per local news reports from the scene.

Jarringly, that was the 14th time Ascend’s Covington plant called in emergency teams. Not all those calls included outright fires, and nobody was injured in any of them, plant manager Andrew Gardner told WSB-TV. But the track record has the city’s mayor worried about the safety of hosting such a facility in the community.

Some of those calls involved workplace injuries and concerns unrelated to lithium-ion batteries, Frey noted to Canary Media. Nonetheless, the latest incident was the biggest thermal event so far; it destroyed the trailer and left some burn marks on the exterior of the nearby building but did not enter the structure. The cause seems to have been batteries that were not properly packed or discharged prior to shipping.

“Since then we have gone on a blitz with all of our customers to redo training on how to pack end-of-life batteries and scrap,” Frey said. “We’ve stopped operations for 10 days to work really closely with the Fire Department and the mayor to show them we’re doing everything we can to ensure safety.”

This story originally appeared in New York Focus, a nonprofit news publication investigating power in New York. Sign up for their newsletter here.

New York state is one step closer to banning fossil fuels in new buildings.

On Friday, the State Fire Prevention and Building Code Council voted to recommend major updates to the state’s building code, which is updated every five years and sets minimum standards for construction statewide. The draft updates include rules requiring most new buildings to be all-electric starting in 2026, as mandated by a law passed two years ago.

The vote came after the code council went missing in action for more than two months, leaving some advocates nervous that the state might be wavering on the gas ban. With the rules now entering the final stage of the approval process, New York remains on track to be the first state to enact such a ban.

The new draft code also tightens a slew of other standards in a bid to make buildings more energy efficient and save residents money over the long term. But it leaves out several key provisions recommended in the state’s climate plan — possibly running afoul of a 2022 law.

Specifically, the draft energy code leaves out requirements that new homes include on-site energy storage and be wired such that owners can easily add electric vehicle chargers (when the property includes parking space) and solar panels. The state’s 2022 climate plan listed these three provisions as “key strategies” to achieve New York’s legally binding emissions targets. On-site energy storage also makes homes more resilient when disasters strike, the plan noted, providing backup power in the event of a blackout.

A separate 2022 law required the state to take those recommendations into account when updating its building code.

“Updating the infrastructure for those things is a key part of what this transition is,” said Michael Hernandez, New York policy director at the pro-electrification group Rewiring America.

The Department of State, which oversees New York’s code development process, did not respond to a request for comment.

Buildings are New York’s largest source of emissions, according to the state’s accounting, amounting to nearly one-third of all climate pollution. New York’s buildings burn more fossil fuels for heat and hot water than any other state’s, according to the clean-energy group RMI. That contributes not only to global warming but also to local air pollution, with deadly consequences: A 2021 study by Harvard researchers found that pollution from New York’s buildings causes nearly 2,000 premature deaths a year.

Cutting that pollution will require major upgrades to the state’s aging housing stock — an enormous challenge. But climate hawks stress that the first and easiest step is to stop digging the hole deeper, by making new buildings as climate-friendly as possible. Making them all-electric is a key part of that. But other, subtler changes can also play an important role.

The fossil-fuel industry, for its part, is taking those changes seriously. Gas trade groups led a major fight to keep provisions such as the EV-ready requirement out of the national building code that provides a model for states including New York. After nearly five years of wrangling, the International Code Council — actually a national nonprofit — that oversees the process voted not to include the provisions as requirements, siding with the gas groups over the advice of its own experts.

Among the parties who stood up for the stricter energy code: a New York state code official, who joined advocates like Hernandez one year ago in urging the International Code Council to keep the requirements in. Yet the state is now following the national group’s lead and relegating the solar, electric vehicle, and battery standards to the appendices of its draft code. That means they can still serve as templates for localities that want to adopt the tougher standards, but they’re not required.

Fossil-fuel interests and some Republican lawmakers have argued that including such mandates would only drive up the cost of new homes at a time when housing is already deeply unaffordable. But climate advocates point out that it’s far cheaper to install electrical infrastructure up front than add it in later on — as much as six times cheaper in the case of an EV charger, for example.

That’s in keeping with many of the green rules that New York did include in its new draft code. Chris Corcoran, a code expert at the state energy authority NYSERDA, told the code council on Friday that adopting the full suite of proposed energy rules will add about $2 per square foot to the up-front cost of new homes but save residents more than three times that over 30 years.

It’s not entirely clear who in New York has pushed to leave the storage, solar, and EV provisions out. Only eight groups disclosed that they lobbied on the building and energy codes last year, and it’s not obvious that any of them had a specific interest in opposing those rules.

Officials speaking at Friday’s meeting did not explain why they left out the requirements. One lawyer who helped draft the updated energy rules, Ben Kosinski, left the Department of State just this month to work as chief counsel for the Senate Republicans, for whom he also worked before joining the code office, according to his LinkedIn profile. The GOP caucus has voted almost unanimously against the laws driving the pro-electrification updates to the code. (Kosinski did not immediately reply to a request for comment.)

Although the council voted unanimously on Friday to advance the all-electric rules, not all members supported the move. William Tuyn, a builders’ representative from the Buffalo area, noted that the state adds roughly 40,000 homes a year — a tiny fraction of the roughly 7 million that already exist.

“We don’t even make a dent in the issue of climate change by focusing there,” he said in the final minutes of the meeting. “The Legislature did what they did. That ship has sailed … [but] we really need to concentrate on renewables or improving the grid if we’re really going to be able to do something and we’re not just going to simply crash the economy of the state of New York.”

Several lawmakers urged the council on Friday to include the full suite of climate provisions in the final rules.

“These provisions are not trivial add-ons. They are the backbone of a truly effective energy code,” said Neil Jimenez, legislative director for Assemblymember Yudelka Tapia. “Their exclusion weakens the very foundation upon the policies we’ve fought so hard to put into place here in Albany.”

Since its founding back in 2010, Shine Technologies has raised nearly $800 million to deliver on the potential of generating cheap, abundant energy from fusion.

Like the dozens of other startups at work in this field, Shine Technologies has yet to crack the code on fusion, an energy source that has been 40 years away from commercialization for 50 years. But unlike those competitors, Shine is already generating real revenue — not by producing electricity but by essentially selling neutrons from the fusion reaction to industrial imaging and materials testing companies.

Governments, venture capitalists, tech billionaires, and other private investors around the world have pumped more than $7.1 billion into fusion companies, according to a July 2024 report by the Fusion Industry Association.

But despite almost a century of research since fusion’s discovery, engineers have been unable to achieve its holy grail: continuously generating more power than was used to create a fusion reaction in the first place. The fusion world uses a metric called the fusion energy gain factor, also known simply as Q, to measure that ratio. If a project was to achieve a Q greater than 1, it would achieve the much-sought-after energy-breakeven point.

But Shine has a different benchmark — at least for right now.

“If you talk to almost every fusion company on Earth, they’ll say, ‘We’re shooting for Q greater than 1.’ But we have a different Q — our Q is economic. It’s generating more dollars out than dollars in. That’s how you scale a company,” Greg Piefer, Shine’s CEO, said.

The fusion reaction is the primordial alchemical trick that powers our sun, propels spacecraft in science-fiction novels and, if the visionaries and true believers are correct, could meet humanity’s voracious energy needs in the centuries to come.

The reaction occurs in plasma, the fourth state of matter. The sun creates plasma by compressing and heating hydrogen to tens of millions of degrees, and it performs the miracle of fusion by confining that hydrogen, along with its variants, with its mammoth gravity.

Humans hoping to recreate the conditions of the sun on Earth have to rely on exotic magnets, Brobdingnagian laser-beam arrays, or other maximalist techniques.

These complex and expensive fusion machines compress and confine plasma in an attempt to bring two nuclei close enough to overcome their repellant electrostatic forces and fuse together. A successful, sustained fusion reaction would heat up a material surrounding the reactor, allowing it to boil water and drive the same sort of conventional steam turbine you’d find in a coal, gas, or traditional nuclear (fission) power plant.

Most of the fusion startups Canary Media has covered — such as Commonwealth Fusion Systems, TAE Technologies, Avalanche Energy, and Zap Energy — plan to take this steam-turbine approach to producing fusion power. Each company has its own (unproven) method for controlling the plasma and wringing out the heat. Some firms use a tokamak design, a very big, hollow donut-shaped hall in which the plasma circulates, or a twisted variant called a stellarator. Some aspirants confine the plasma with magnetic forces while others use high electrical currents or lasers to tame the atomic-particle soup.

So, which technology and approach is Shine using to solve the fusion riddle?

“I’m going to say something really trippy. As a fusion company, when it comes to energy production — I don’t know yet. … We have our own internal technological approach. I don’t think it’s any more likely than any other technological approach to prevail,” Piefer admitted. “You won’t hear that from any other fusion CEO in the whole world. But the truth is, it’s early innings, and we don’t know which fusion approach is going to be the most cost-effective.”

And while today’s cadre of fusion startups aims to provide power to the electrical grid in the 2030s or 2040s, Shine is following a different path to market.

“Fusion-energy people are trying to go from fusion not really having ever been used commercially for anything to it being the most reliable, cheapest form of generating energy,” said Piefer. “Everyone’s chasing the energy.”

Instead, Shine’s CEO wants his firm to scale the way historic deep-tech companies like semiconductor makers have done: “You start small with a market where you can make money right away, and then you iterate over time — and through that virtuous cycle of providing value and reinvesting a portion of it to make the technology better, you continue to access bigger and bigger markets.”

The market where Shine is making money now is the sale of neutrons for use in industrial imaging and materials testing. Piefer estimates that this will generate “on the order of $50 million of revenue in 2025.”

Shine will next move into medical-isotope production, then recycling spent nuclear fuel, and, ultimately, Piefer said, electrical power generation.

Producing medical isotopes requires fewer sustained reactions than producing power, and while net power is a ways away, the technology for isotope production is already available.

Medical isotopes are currently produced via nuclear fission, but if they can be produced via fusion, that would eliminate the need to use highly enriched uranium. And it could be a lucrative line of business: The global market for medical isotopes is about $6 billion a year.

“If you make a kilowatt-hour of fusion energy, you can sell that kilowatt-hour for maybe 5 cents,” he said. “But you can sell the other product of [deuterium-tritium] fusion reactions, neutrons, for as much as $100,000 per kilowatt-hour in certain markets.”