Maine’s solar incentive program has become a political scapegoat for rising electricity prices in the state, but clean-energy advocates say the numbers don’t add up.

Maine utility customers pay some of the country’s highest electricity prices, but the portion of their monthly bills that goes toward buying surplus power from neighbors’ solar panels has actually decreased in recent months, according to one analysis.

Meanwhile, the amount of money utilities are paying for power from fossil fuel–fired plants and transmission represents a far bigger share of the electricity-bill bottom line.

“It’s an easy narrative to say ‘Solar panels are being built in this field, and electricity prices are going up,’” said Lindsay Bourgoine, director of policy and government affairs at solar company ReVision Energy. “But that’s not actually what’s happening when you look at the data.”

Maine Republican lawmakers this session have introduced four different bills calling for the repeal of net energy billing, the system that compensates utility customers for unused electricity they generate and share on the grid. Supporters of the bills have called the program a “job-stealing solar energy tax,” though it’s not a tax: Utilities compensate the owners of solar panels for excess energy sent to the grid, then spread the cost out among ratepayers.

“What’s really troubling in Maine is that there is this growing narrative that the rise in utility bills is directly attributable to solar,” said Eliza Donoghue, executive director of the Maine Renewable Energy Association. “It’s not true.”

The hostility toward Maine’s net energy billing rules is part of a wave of efforts to blame rising power prices on clean-energy and energy-efficiency programs, particularly in New England. In Rhode Island and Maryland, legislators have called for cuts to fees supporting energy-efficiency and clean-energy programs. And Massachusetts regulators last week ordered $500 million to be cut from the state’s energy-efficiency plan, following utilities’ claims that these money-saving programs have been a major driver of rising energy bills.

At a legislative committee hearing last week, Maine legislators testified that small-business owners will be forced to close their doors and low-income households put in dire financial straits by wealthy solar-panel owners imposing the cost of their renewable-energy choices onto everyone else. It is “a nefarious scheme,” said Sen. Trey Stewart, a Republican and the sponsor of one of the bills. “We risk collapsing our entire economy,” said Republican Sen. Stacey Guerin, the sponsor of another.

The numbers tell a very different story, beginning with the actual dollars-and-cents impact of net energy billing on the average consumer.

Maine’s net energy billing program was expanded in 2019, increasing its cost but also spurring new solar development. By the end of 2024, the state had more than 1,500 MW of solar capacity, up from less than 100 MW in 2019.

Statewide, costs attributed to net energy billing now make up a slightly smaller percentage of the average bill than they did in the latter half of 2024, according to calculations ReVision made using information from utility filings. For Versant Power residential customers using 500 kilowatt-hours per month, net energy billing adds between $6.40 and $7.62 to the monthly bill depending on their exact location, according to a spokesperson for the utility. Central Maine Power residential customers pay on average $7.06 per month for costs related to net energy billing, a spokesperson for the company said.

So if it’s not the solar program, then what is causing utility bills to rise? One of the main forces driving electricity prices is the cost of energy supply in New England, more than half of which comes from natural gas–fired power plants. Volatility in the natural gas market, therefore, translates directly into higher electricity rates for consumers. Prices spiked in 2022 and 2023, for example, as the war in Ukraine pushed the cost of natural gas up worldwide. This year, energy supply accounts for 39% of a typical Maine household’s monthly bill — roughly nine times the cost of net energy billing — according to ReVision’s numbers.

“Solar isn’t the problem. Fossil-fuel volatility really is,” Bourgoine said.

The other major contributor is rising transmission costs, which on average make up 51% of electricity bills, up from 37% in the second half of 2023.

There are some commercial cases in which the cost for net energy billing does have an outsized impact on energy bills, supporters of the incentive agree. Commercial power customers are charged a fixed rate based on the specific rate classification their business falls under. This system means some businesses end up with a much larger percentage of their bill paying for net energy billing.

At last week’s hearing, Sen. Stewart testified that potato processor Penobscot McCrum will pay close to $700,000 in public-policy charges this year. Roughly 55% of this charge reflects the costs of net energy billing, according to utility Versant.

Supporters of net energy billing agree that situations such as these are unfair and unsustainable, and a docket is already underway with the state Public Utilities Commission to address that specific issue without repealing the entire net energy billing program, Donoghue said.

“There is a certain amount of customers that, we agree, should be complaining,” she said.

Net energy billing also provides benefits that are hard to see but which offset the costs, supporters said. In 2023, the program cost ratepayers $130 million but delivered $160 million in benefits to the state, according to an independent analysis prepared for the Public Utilities Commission. By adding solar power to the grid, the program helps suppress wholesale electricity prices, for example, and it improves reliability because there cannot be a shortage of “fuel” for solar generation.

More solar generation in the state means more Maine households are getting power produced in or near their communities, lowering the strain on the transmission and distribution systems — and the associated costs. Solar developers also pay for any infrastructure upgrades needed to accommodate their projects.

“Those are investments that utilities don’t have to put on ratepayers,” said Jack Shapiro, climate and clean energy director for the Natural Resources Council of Maine.

Furthermore, eliminating net energy billing would have its own financial consequences for the roughly 110,000 customers enrolled in the program. The abrupt end of all net energy billing would leave these participants — including residents, businesses, and schools – without promised and planned-for savings, Shapiro said.

Opponents in the legislature have passed three rounds of rollbacks to the program. Now they want to go even further.

“If [these bills] were passed, they would actually have some truly disastrous consequences for a lot of people and schools and municipalities,” Shapiro said.

U.S. manufacturers rely on more than 30,000 small industrial boilers to make a large number of things: foods, drinks, paper, chemicals, clothes, electronics, furniture, transportation equipment, and more.

The vast majority of these smaller boilers burn fossil fuels — mostly gas, but sometimes coal or oil. Their emissions contribute not only to climate change but to smoggy skies and elevated asthma rates, too.

Swapping out such boilers for electric industrial heat pumps would be a quick win for communities and regulators looking to improve air quality, said Hellen Chen, industry research analyst at the nonprofit American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, or ACEEE.

Only about 5% of process heat in industry currently comes from electricity, but industrial heat pumps are gaining some momentum. They’ve already been installed in at least 13 American factories, helping reduce pollution from brewing beer, pasteurizing milk, and drying lumber. Kraft Heinz, the famed ketchup and mac-and-cheese maker, plans to install heat pumps at 10 factories by 2030. Oat-milk producer Oatly is considering one at a New Jersey plant. And policymakers in Southern California passed a rule last summer to phase out industrial boilers, a move that will likely boost heat-pump replacements.

Industrial boilers spew a panoply of air pollutants as byproducts of combustion, including nitrogen oxides, or NOx. NOx is harmful in itself but also contributes to the formation of ozone, a key ingredient of smog that can inflame airways and cause a range of respiratory problems, especially in children whose lungs are still developing.

To identify opportunities to clean up air quality, Chen and ACEEE colleagues recently mapped areas where ozone levels exceed the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency standard, the number of small industrial boilers in each area, and the fuel they use. In total, they found that more than 5,400 boilers currently burn in 174 counties. The team focused on smaller industrial boilers, defined as having capacities up to 50 million British thermal units per hour, because their emissions are often overlooked, yet the equipment is the easiest to switch out for heat pumps, Chen said.

“In areas where the baseline community pollution burden is already high, there is a really important opportunity,” Chen said. Heat pumps are “a cleaner and more efficient technology that is ready for adoption today.”

Depending on the boiler size, fuel type, and other aspects, the reduction in onsite NOx emissions from swapping just one industrial boiler for a heat pump is equivalent to taking 400 to 10,000 cars off the road, by Chen’s calculation.

The industrial emissions reductions would add up. Some counties host large stocks of these smaller boilers: Cook County, Illinois, has 297; Philadelphia County, 127; Harris County, Texas, 123; and Los Angeles County, 111, per the ACEEE map.

Heat pumps are available now for low-temperature industrial processes, making them well-suited to industries like food and beverage manufacturing, which relies almost exclusively on heat below 266 degrees Fahrenheit (130 degrees Celsius). Low-temperature heat also plays a significant role in areas like chemicals and paper production.

Industrial heat pumps, which were first developed in the 1980s, are wildly energy efficient and can use just one-third to a quarter as much energy as boilers. Depending on the relative prices of gas and electricity, that superior efficiency can deliver lower operating costs.

Heat pumps can also improve product quality by providing more precise temperature control. Back in 2003, the Department of Energy found that heat pumps produce higher-quality dried lumber.

Plus, heat pumps can have a smaller physical footprint than boilers with similar capacities since they don’t store fuel, making them advantageous for facilities with limited floor space. Since they’re modular, they can be installed in parallel to meet heat demands as needed, Chen said.

Added up, these and other co-benefits can save facilities another 20% to 30% on top of reduced energy costs.

The major impediment to switching out combustion boilers, which can last 20 to 40 years or more, is the upfront cost. The payback period for an industrial heat pump retrofit is typically on the high side — between five and seven years, Chen said.

“Unfortunately, many companies are looking for very short ROIs [returns on investment] of under three years,” Chen said, making the business case difficult even if the lifetime savings are great. In new facilities, heat pumps can cost the same as gas boilers to install, she noted.

Policy support can make it more logical for a business to take on these upfront costs.

At least one air quality regulator is beginning to push industries to decarbonize. Last year, California’s South Coast Air Quality Management District passed a first-in-the-nation measure that aims to gradually phase out NOx emissions from 2026 to 2033 from more than 1 million large water heaters, boilers with capacities of up to 2 million British thermal units per hour, and process heaters in the area, which will necessitate the switch to electric tech.

Chen hopes to see more regulators follow the district’s lead as well as tackle what is to her the biggest hurdle to electrification in the U.S.: the relatively high cost of electricity compared with gas, known as the “spark gap.”

The spark gap, the ratio of average electricity price to fossil-gas price (each in dollars per kilowatt-hour), varies from state to state. A ratio of less than about three to four typically makes switching to a heat pump more economically feasible without additional policy support because industrial heat pumps are about three to four times as efficient as gas boilers and thus can lower operating costs, Chen noted.

Electric utilities and regulators could redesign rates to make the electric equipment more attractive. The idea has precedent for home heat pumps, though hasn’t been realized for industrial ones yet, as far as Chen’s aware.

State and federal programs are also helping to defray the capital costs of electrifying.

California provides $100 million for electric upgrades at factories through the Industrial Decarbonization and Improvement of Grid Operations program. Colorado offers competitive tax credits — up to $168 million in total — for industrial facilities to install improvements that reduce greenhouse gases. Under the Biden administration, about $500 million was granted to Kraft Heinz and others for projects cleaning up emissions from process heat, part of a $6 billion windfall for industrial-decarbonization demonstration projects. But the fate of the awards is unclear as the sweeping federal funding freeze ordered by President Donald Trump in January has, so far, failed to fully thaw.

With momentum growing for zero-emissions equipment like heat pumps, “we’re hoping that … more facilities will see them as a viable technology that’s ready to go,” Chen said, and that companies “will be more confident about applying this technology within their own facilities.”

Sunnova, one of the country’s largest residential-solar companies, has warned investors that it may run out of money within the next 12 months. It’s a snapshot of a company struggling to maintain financial viability amid a punishing economic climate for rooftop solar installers and financiers.

The “going concern” warning came during Sunnova’s fourth-quarter and fiscal-year earnings statement on Monday. The news sank the Houston-based company’s stock price from about $1.60 per share on Friday evening to a low of 56 cents per share on Monday morning. (Sunnova shares were trading at about 60 cents as of market close on Monday.)

Sunnova’s revenue grew to about $840 million in 2024, up from nearly $721 million in the prior year. But the company’s net losses before income taxes of almost $448 million last year were little improved from just over $502 million in 2023. The losses stemmed from declining sales of solar energy systems and products alongside rising operating expenses.

Over the course of the year, Sunnova was unable to increase the amount of unrestricted cash and commitments under existing financing arrangements to fund its business. The company, which finances rooftop-solar and battery installations conducted by independent installers, laid off about 300 employees, or about 15% of its workforce, in February.

As of Friday, these unrestricted funds were “not sufficient to meet obligations and fund operations for a period of at least one year from the date we issue our consolidated financial statements without implementing additional measures,” the company stated.

A Sunnova spokesperson told Canary Media on Monday that the company is “confident in our ability to manage our obligations and position Sunnova for long-term success.”

The bad news from Sunnova comes amidst a tough economic picture for U.S. rooftop solar overall. The nation’s residential-solar installations were forecast to decline by roughly 26% in 2024 compared to 2023 in a December report from analytics firm Wood Mackenzie and the Solar Energy Industries Association trade group — the market’s first annual drop in at least four years.

“When interest rates began to really escalate, more than two years ago, it put a damper on demand for residential solar across the United States,” said Pavel Molchanov, investment strategy analyst at financial services firm Raymond James. “The cost of capital for residential solar correlates with what’s happening with the broader interest-rate environment.”

The Federal Reserve started cutting rates last fall. But the economic and trade policies instituted by President Donald Trump have raised fears of a potential economic downturn and increasing inflation, tamping down expectations of near-term interest rate cuts.

Among different types of solar power, “residential solar is near the high end of the spectrum” in terms of its sensitivity to interest rates, Molchanov added.

That’s in part because residential rates tend to be higher from the start. Unlike utility-scale solar projects, which are backed by power purchase agreements from utilities or large corporate customers, residential projects are “ultimately tied to individual homeowners,” Molchanov explained, increasing the perceived risk of default — and raising the interest rates they are offered as a result.

Sunnova CEO John Berger said in a Monday statement that the company has “acted on several initiatives” to improve its financial picture, including “raising price, simplifying our business to reduce costs, and changing dealer payment terms,” which are intended to “support positive cash in 2025 and beyond.”

But Sunnova’s financial position may make it difficult for the company to raise the capital it needs, at least at reasonable terms. The company stated on Friday that it had secured a $185 million loan at a 15% interest rate, which is well above typical corporate borrowing rates, to use for “general working capital purposes.”

The interest-rate environment has helped drive a number of residential-solar companies into bankruptcy in the past two years, including SunPower, one of the country’s oldest solar companies. Some of SunPower’s assets have been bought by residential installer Complete Solaria.

Sunrun, the country’s largest residential solar and battery installer, also reported declining revenue and increasing losses in 2024 compared to the previous year in an earnings statement last week.

Beyond interest rates, Sunnova and other residential-solar installers have had to contend with a dramatic shift in California’s residential-solar policy, Molchanov said. The state is by far the largest rooftop-solar market in the country.

In April 2023, California regulators sharply reduced the net-metering rates that owners of rooftop solar systems can earn for the electricity they feed back to the power grids operated by the state’s three large investor-owned utilities. Residential solar installations have dropped sharply since that change, and many solar companies in the state have laid off workers or closed their doors.

California’s cutback on net metering “put a damper on demand, compounding the effect of high interest rates,” Molchanov said. Residential-solar sales in the state have grown slightly in recent quarters but remain far from their pre-2023 highs, according to the California Solar and Storage Association trade group.

Residential solar could be hampered further by the Trump administration and Republican-controlled Congress.

After Trump’s election, publicly traded clean-energy companies including Sunrun and Sunnova took hits in the market due to fears that the president’s antipathy to climate and clean-energy policy could drive Congress to undo or weaken federal tax credits that play a central role in boosting the economics of solar power. Trump’s decisions on tariffs could also raise the cost of solar systems.

Sunnova has itself previously been targeted by Republicans in Congress. In 2023, the company won a $3 billion loan guarantee from the U.S. Department of Energy to support its effort to lower consumer costs for financing “virtual power plants” — solar systems bolstered by batteries that can help reduce peak energy.

Rising electricity costs are one of the few tailwinds for residential solar, Molchanov said. Utility rates have been climbing in many parts of the country, which can make generating one’s own electricity more attractive by comparison. More households are also looking to residential systems for reliability purposes, choosing to pair batteries with solar to provide power during grid outages.

“But the No. 1 variable we need to watch is interest rates,” Molchanov said. “The higher they go, the more difficult it will be for residential solar in the aggregate in this country.”

Since 2017, sweeping legislation in Illinois has sparked a solar-power boom and launched ambitious energy-equity and green-jobs programs.

Now, for the third time in under a decade, state lawmakers, advocates, and industry groups have their sights set on ensuring that clean energy momentum.

The focus this legislative session is the electric grid. Stakeholders worry the state’s clean energy progress will stagnate if it can’t expand and fortify its infrastructure for moving and storing electricity.

Advocates are backing a wide-ranging bill known as the Clean and Reliable Grid Affordability Act, or CRGA, which they describe as the successor to the 2017 Future Energy Jobs Act and the 2021 Climate and Equitable Jobs Act. Solar and energy-storage industries are backing another bill that includes even more ambitious goals for building out new transmission and energy storage.

There’s widespread agreement that Illinois’ current grid is not ready for the state’s mandated transition to 100% clean energy by 2050, especially as overall electricity demand climbs thanks to the proliferation of data centers in Illinois. As in other states, Illinois’ long interconnection queues and lengthy transmission planning processes through the regional transmission organizations make it hard to connect renewable energy sources.

CRGA, introduced Feb. 7, aims to make more efficient use of existing grid infrastructure through a transparent audit of the current system and the adoption of grid-enhancing technologies. It would facilitate new transmission buildout by making it easier for merchant transmission developers to get state permits and by allowing high-voltage transmission lines to be built in highway rights-of-way. It also calls for 3 gigawatts of new energy storage to be added to the grid.

“Transmission is crucial to a reliable and affordable grid because it allows us to move clean energy from place to place and be more resilient in cases of extreme weather,” said James Gignac, Midwest policy director for the Union of Concerned Scientists’ climate and energy program.

The industry-backed transmission and storage bill (HB 3758), introduced Feb. 7, calls for 15 GW of new energy storage, which the bill’s backers say would save consumers $2.4 billion over 20 years. The bill calls on the Illinois Power Agency, which procures energy for the state’s utilities, to also procure energy storage. Gignac said studies by advocacy groups indicate 3 GW of storage is sufficient for the near-term. Both industry and advocacy groups backed a “skinny bill” that passed in the legislature’s January lame-duck session, launching an analysis of energy storage needs by the Illinois Commerce Commission, due on May 1.

Stakeholders generally agree that new energy legislation is especially crucial given the Trump administration’s rollbacks to clean energy incentives and mandates.

“A lot of federal funding we just don’t know the future of, so the role of states and local governments is more important than ever now,” said Jen Walling, executive director of the Illinois Environmental Council.

Illinois does not do the type of comprehensive planning for energy use and transmission that electric utilities do in states with vertically integrated energy markets. In Illinois, separate companies generate and transmit electricity, with the idea that the open market will match supply with demand. But experts say centralized planning is necessary to ensure that clean energy can meet the state’s needs.

“The market is not necessarily going to get us where we need to go on resource adequacy and reliability,” said John Delurey, Midwest deputy program director of the advocacy group Vote Solar.

CRGA calls on the state to undertake a clean-resource planning process involving the commerce commission, state Environmental Protection Agency, and Illinois Power Agency, similar to what utilities in other states do with integrated resource plans.

The bill also mandates public studies of the grid to determine where it is underutilized and how the latest technology could more efficiently move electrons around — increasing the grid’s capacity without building new wires.

“A lot of incumbent transmission owners have confidence in their traditional approaches and tend to rely on those” instead of adopting new grid-enhancing technology, said Gignac. As an example, he pointed to software that can help grid operators reroute power through less congested pathways, a tool reminiscent of Google Maps for road traffic.

“There’s potentially a financial disincentive for [companies to embrace] some of these technologies,” Gignac added, “because they can often be cheaper solutions” than building new transmission, which earns companies a guaranteed profit from ratepayers. Clean energy advocates say more transmission lines are needed, but they want a comprehensive study to know exactly where and how much.

“We are at a point in transition where we have to get even more precise,” said Delurey. “That precision is crucial for affordability. How do we make sure we build exactly what we need? No more, no less.”

Last year, companies hoping to build new high-voltage transmission in Illinois backed a proposal for creating renewable energy credits to incentivize it, similar to those that helped Illinois grow its solar capacity manyfold to over 3.5 gigawatts in less than a decade since the passage of the Future Energy Jobs Act.

CRGA does not include such incentives, but it would make it easier for companies that have not previously built transmission in Illinois to get authority from state regulators to do so, Gignac explained.

This could help the company Soo Green construct its planned 350-mile underground transmission cable connecting Iowa and Illinois. Such merchant transmission lines don’t have to go through the lengthy bureaucratic process that new projects built through regional grid operators’ planning programs do.

Meanwhile, both CRGA and the industry-backed storage bill would create a virtual-power-plant program, wherein companies would aggregate and market the capacity of individual batteries owned by residents, businesses, industries, and even vehicles plugged into the grid.

CRGA would also create an Illinois Storage for All program, mirroring the existing Illinois Solar for All initiative, which helps income-qualified customers, nonprofits, and government entities get solar for little or no cost. The same pot of state funds could subsidize batteries for residents, schools, churches, and others.

“That person is now a resilience hub for the neighborhood,” said Delurey. “Neighbors can come over and stay cool in summer, keep medicine cold in the fridge. For the nonprofit and public facility program, it’s the same idea on a larger scale.”

The bill also greatly expands energy-efficiency mandates for the state’s electric and gas utilities. It increases the amount of energy savings that electric utilities are required to achieve each year to the equivalent of 2% of their annual sales. The utilities do this through funding programs like home weatherization and subsidized efficient appliances.

Under the legislation, downstate utility Ameren would have to meet the same targets as Chicago-area utility ComEd, closing a gap between the utilities’ requirements. It would also more than double the savings mandates for natural gas utilities, and it would end the current ability of large industrial users to opt out of paying into a fund for energy efficiency.

“These are important ways to be moving the needle and prioritizing affordability across the board and even more so for Illinoisans who are financially challenged, historically disadvantaged,” said Kari Ross, Midwest energy affordability advocate for the Natural Resources Defense Council. “Investment in energy efficiency is critical for affordability and … getting the grid reliable and moving toward a clean energy future.”

CRGA has planning requirements and transparency mandates specifically for rural cooperatives and municipal utilities. This is especially important since residents who are member-owners of those entities may understand little about contracts they get locked into, said Andrew Rehn, climate policy director of the Prairie Rivers Network, an environmental group in downstate Illinois. One example of such an agreement is the highly controversial and financially troubled Prairie State Energy Campus, a massive coal plant.

“It’s good governance, trying to make sure the way cooperatives are operating is transparent and interested members can have clear pathways to engaging, understanding what’s going on, having a voice,” Rehn said.

“We think if they did some of this planning we’d see different outcomes. We would be looking at a more diverse portfolio,” changing the fact that “a lot of these municipal utilities and co-ops are still on coal, [and] they will be the last in the state still on coal.”

Two separate bills have been introduced related to the municipal-utility and rural-cooperative transparency demands and to help muni and co-op customers more easily install solar. A Solar Bill of Rights for such customers was also introduced last year.

Advocates say they expect energy bill negotiations to continue throughout the spring session, as they try to gain industry support for CRGA and add elements — like provisions related to data centers — that were discussed but not included in the current legislation.

“In a Trump world nothing feels certain,” said Rehn. “But this feels real. This is the state being able to set our own direction and offset a lot of the horrible things that are going to happen on the federal level. It’s a way we can fight back and do important climate and community-focused work.”

A 67-person Finnish startup called Hycamite has just completed a facility it hopes will revolutionize production of low-carbon hydrogen.

The plant, in the industrial port city of Kokkola, on Finland’s west coast, will soon receive gas shipments from a nearby liquefied natural gas import terminal and turn the fossil fuel into hydrogen. That in itself is not novel — pretty much all of the world’s commercially produced hydrogen comes from methane, the main ingredient in natural gas. But all those legacy hydrogen producers end up with carbon dioxide as a byproduct, and they vent it into the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change. Hycamite will make hydrogen without releasing CO2, using a little-known process called methane pyrolysis.

“We split the methane with the help of catalysts and heat — there’s no oxygen present in the reactor, so that there’s no CO2 emissions at all,” founder and Chairman Matti Malkamäki told Canary Media in a December interview. “We are now entering industrial-scale production.”

Hycamite’s Customer Sample Facility in Kokkola can produce 5.5 tons of clean hydrogen per day, or 2,000 tons per year, Malkamäki said. Instead of creating carbon dioxide as an inconvenient gaseous byproduct, pyrolysis yields solid carbon. Hycamite uses catalysts developed over 20 years by professor Ulla Lassi at the University of Oulu, which transform the methane into “carbon nanofibers with graphitic areas.” This solid carbon can be processed further to produce graphite that Malkamäki plans to sell to battery manufacturers and other high-tech industries.

Hycamite closed a $45 million Series A investment in January to fund operations at the hydrogen plant. But it’s just one of a growing cluster of climatetech startups betting that the dual revenue stream of hydrogen and useful carbon products gives them an edge in the nascent marketplace for clean hydrogen, a much-hyped, little-produced wonder fuel for solving tricky climate problems.

Low-carbon hydrogen theoretically could clean up emissions-heavy activities like long-distance trucking, shipping, steel making, and refining — if anyone can manage to make it, at volume, at prices that compete with the dirty stuff that’s already available. In the U.S., some hydrogen producers and fossil fuel majors have talked about retrofitting carbon-capture machinery onto existing hydrogen plants, but nobody’s built a full-scale “blue hydrogen” operation so far. Renewables developers have evangelized “green hydrogen,” which is made by running clean electricity through water to isolate hydrogen, but they need electrolyzers and the production of clean electrons to get considerably cheaper. Until then, they’ll depend heavily on government policy support.

Now President Donald Trump is treating Joe Biden’s suite of clean energy policies like a piñata, and it’s hard to tell if incentives for producing green hydrogen will even survive. That’s already scaring off investors from large, capital-intensive green hydrogen projects. But the up-and-coming pyrolysis crew could find a niche: Their projects are smaller and nimbler, and they consume natural gas, one sector that Trump has ordered his government to encourage.

Methane pyrolysis entrepreneurs like Malkamäki are heeding the call of fundamental chemistry.

“Thermodynamically, it’s far more energy-favorable to split methane than to split water,” said Raivat Singhania, a materials scientist who scrutinizes hydrogen startups at Third Derivative, a clean energy deep-tech accelerator. Water’s chemical bonds hold together more fiercely than methane. That means companies trying to make clean hydrogen by splitting water need huge amounts of electricity to overcome the strength of its bonds; sourcing that electricity creates a daunting cost and a logistical hurdle.

Not only does methane-splitting require less energy, it can be done with a simpler plant design than water electrolysis, using fewer moving parts or fragile pieces of equipment, Singhania noted. This analysis informed Third Derivative’s investment in Aurora Hydrogen, which breaks methane using microwaves.

Those thermodynamic advantages come with tradeoffs. Namely, would-be methane pyrolyzers need a ready source of methane, which in practical terms means a pipe delivering fossil gas. That inevitably entails some level of upstream emissions.

Methane pyrolyzers also need to be located where gas is abundant. It’d be hard to scale up in places like Europe, post Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, or Massachusetts when winter rolls around. But supply is ample across much of the U.S., which is producing more fossil gas than any country ever. Hycamite is building its commercial test facility in its home base of Finland, but the company is looking to the U.S. to deploy its technology, Malkamäki said.

Right after taking office in January, Trump responded to world records in U.S. fossil fuel production by declaring an “energy emergency” and ordering his administration to clear the way for even more fossil fuel extraction.

It’s not clear whether the fossil fuel industry can or wishes to increase production dramatically; in market-based systems, excess supply tends to deflate prices. Whether production stays at current record highs or pushes further skyward, the U.S. will have plenty of gas to go around, and methane pyrolysis companies could generate the kind of new demand that the industry desperately needs. Moreover, they would be using American fossil fuel abundance to create materials useful for the transition to clean energy.

For that to happen, though, pyrolysis startups need to break through early technical demonstrations and start producing at scale.

Hycamite is not the only company chasing the pyrolysis dream.

The American startup Monolith is arguably furthest along in the quest to turn laboratory science into industrial-scale production. It uses high-heat pyrolysis to produce hydrogen and a dark powdery substance called carbon black, an additive used in tire and rubber manufacturing.

Monolith received a conditional $1 billion loan from the Department of Energy in late 2021 to build out its facility in Nebraska, which would deliver clean hydrogen to decarbonize fertilizer production. Monolith had to run a gauntlet to prove to DOE’s Loan Programs Office that it deserved such a loan. It has the rare distinction among pyrolysis startups of having actually sold its carbon products: Goodyear makes a tire for electric vehicles using Monolith’s carbon black.

However, Monolith did not finalize the loan before the Trump administration came to office and froze new disbursements for clean energy. The company was running short on cash while struggling to get its high-heat process to work reliably around the clock, per a Wall Street Journal article published in September. Monolith secured additional financing from its investors just before that story published.

Several other startups want to boost their revenues by turning methane into higher-value forms of carbon than carbon black, a relatively inexpensive commodity — if they can achieve the quality and consistency necessary to sell into those specialized and demanding markets.

A group of Cambridge University scientists founded Levidian in 2012 to create reliable, large-scale production of graphene, a carbon-based supermaterial discovered in Manchester, England, in 2004. After another eight years of research and development under the moniker Cambridge Nanosystems, the company was acquired and brought to market by a British entrepreneur.

Levidian eschews the catalysts, heat, and pressure that other startups use to split methane. Instead, the team ended up building a nozzle that sucks in methane gas, then uses electricity to generate microwave energy, which in turn creates a cold plasma torch that shaves carbon atoms from hydrogen atoms.

This yields hydrogen and graphene, which can be used in semiconductors, electronics, and batteries. Levidian can sell graphene for hundreds of dollars per kilogram, far more than carbon black, CEO John Hartley told Canary Media in January. Indeed, the company will host its first graphene auction on March 24. To install its technology, though, Levidian has focused on customers who want to clean up their fossil gas emissions.

“It’s really an onsite carbon-capture unit at its core: It catches carbon, makes hydrogen, and decarbonizes methane gas,” Hartley said. The first customers include Worthy Farm, which hosts the Glastonbury music festival; a wastewater treatment plant in Manchester; and the Habshan gas processing facility in Abu Dhabi.

U.S.-based Etch builds on research by founder Jonah Erlebacher, a materials science professor at Johns Hopkins University. The startup splits methane with what it describes as a recyclable catalyst that contains no rare minerals; it produces graphite and other forms of carbon.

The Etch team is wrapping up commissioning for its first “commercial-scale pilot” in Baltimore, a spokesperson told Canary Media. Last fall, the startup brought in a new CEO with commercial chops: Katie Ellet previously served as president of hydrogen energy and mobility for North America at Air Liquide, one of the few companies actually producing low-carbon hydrogen at scale, and a key player in six of the seven hydrogen hubs funded by the Department of Energy.

All these companies need to hit their stride just as the clean hydrogen market has entered a period of tumult.

The Biden administration hoped to jump-start a clean hydrogen economy with two major policies: A suite of billion-dollar grants to seven “hydrogen hubs” strategically chosen around the country, which are intended to link up production with entities that could use the fuel to clean up transportation and heavy industry, and a production tax credit to effectively lower the market price of hydrogen produced using low-carbon methods.

Now, the Trump administration has frozen payments on clean energy grants and loans. Prospective hydrogen producers had been waiting breathlessly for the final IRS guidance on the 45V tax credit; now that the lawyers have finally produced that guidance, the nascent hydrogen industry has to plead with the new administration to preserve those credits as it overhauls federal spending this year.

Given this swirling uncertainty, pyrolysis startups can take some solace in the fact that their business is not entirely dependent on the vagaries of hydrogen policy. At least they can sell carbon materials, which have clear value and established buyers who use the stuff in a non-theoretical way.

I asked Malkamäki if Hycamite identifies as a carbon company that also makes hydrogen or a hydrogen company that also makes carbon. He pointed out that the company name itself is a mashup of “Hy-” for hydrogen and “ca-” for carbon (and the -mite is a reference to a fanciful super-fuel that Donald Duck invented in a vintage comic strip). The revenues from the carbon products are “elementary for us to be profitable,” he said. “A couple of investors have said to us that hydrogen makes you sexy, carbon makes you money.”

That’s not to suggest breaking into the battery supply chain will be easy. It requires passing rigorous, multi-year testing by the battery makers that might buy Hycamite’s carbon products. But this kind of revenue can bolster a young business as it rides out the storm in Washington.

This story was originally published by Capital B, a nonprofit newsroom that centers Black voices and experiences. To read more of Adam Mahoney’s work, visit Capital B.

Ninety years ago, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and South Carolina Gov. Ibra Blackwood worked together to bring electricity to rural South Carolina. But to build the power plant that would make it happen, they destroyed the homes of 900 Black sharecropping families. With them, 6,000 graves — including those of formerly enslaved people — were removed or desecrated.

Today, as South Carolina races to power its digital future, history seems to be repeating itself, with Black communities once again paying the price for progress.

Last year, the parent companies of Facebook and Google pledged more than $4 billion for new data centers in South Carolina. Every email you send, question you ask ChatGPT, or Instagram post you share relies on these centers. However, on this new digital frontier, the health and safety of Black communities are at risk.

While state officials work to craft legislation to attract these new projects, residents and community advocates say this will ramp up environmental hazards, increase utility bills, and exacerbate health disparities. Meanwhile, experts say, the economic promise of AI remains a mirage for Black communities, widening wealth gaps and displacing workers.

“Most Black households, especially rural ones in the South, are not using AI or as much computing power, but they are having to pay for that demand in both money and dirty air,” said Shelby Green, a researcher at the Energy and Policy Institute.

South Carolina is joining other states, like Texas and Illinois, with proposals to reopen at least two power plants in rural Black communities to run these new projects. Rural communities have begun to attract tech companies for data centers due to their low population densities, ample open space, and relatively lower energy and land costs.

Energy experts argue that the growing electricity demands from data centers are prolonging America’s dependence on dirty energy sources. Nationwide, at least 17 fossil fuel generators scheduled for closure are now delayed or at risk of delay, and about 20 new fossil fuel projects are being planned to meet data centers’ soaring energy demands. By 2040, South Carolina projects the need for four new fossil fuel power plants.

At a protest last year, Audrey Henderson, a resident of one of the towns facing the prospect of a polluting power plant, said she fears the impacts on her and her neighbors’ properties.

“My forefathers worked hard to get that property; that we have land. I have children in New York to get land when I pass away. Grandchildren and so forth and so on,” she said. The fact “they could just come in here, give us a couple of dollars, and take our land and put pipelines into it. Then we also have well water, just stuff going into the wells is very disheartening, and I’m really concerned.”

Across the country, low-income Black communities face the harshest pollution exposure from these plants, while Black workers are disproportionately in roles most vulnerable to AI and automation. A McKinsey & Co. analysis warns that if AI growth continues at its current pace, the wealth gap between Black and white households could widen by $43 billion annually within the next two decades because of disparities in who it serves.

Compounding these issues, data centers are expected to use 12% of the nation’s energy by 2028, a 550% increase from last year. An artificial intelligence search using ChatGPT, for example, uses anywhere from 10 to 30 times more energy than a regular internet search.

“The energy demand, data centers, and where the energy sector is going should not come at the expense of low-income and Black communities,” said Xavier Boatwright, an activist who has worked on environmental issues in rural South Carolina for years.

In South Carolina, officials predict data centers will drive 70% of the state’s increased energy use, with subsidies already raising utility bills for consumers. Through his canvassing across the state, Boatwright said he now regularly sees rural mobile home communities where people are paying more for their utility bills than mortgages because of this increase.

“It’s kind of like if you go out and your employer is paying for your dinner, and you order the fanciest stuff on the menu,” explained Green, who researches how rising utility bills are pushing Southern Black communities into poverty. “You don’t really have to worry about how expensive it is because it’s not coming out of your pocket. That’s how these companies are operating; they’re not holding the risk associated with increasing electricity costs and these new power plants — you are.”

In majority-Black, poor rural Fairfield County, the state is proposing to reopen a stalled nuclear plant that has long been a symbol of broken promises and financial strain for residents. Advocates warn that restarting this decades-long gamble could further burden a population already facing systemic neglect. Billions of taxpayer dollars and rising energy costs are at stake, yet the benefits of the project seem unlikely to reach those facing the worst consequences.

In South Carolina, and across the country, statistically, Black people use the least amount of electricity, yet experience the highest energy burden — meaning a larger share of their income goes toward energy bills.

In the other case, a Black stronghold in Colleton County celebrated the monumental victory of closing a coal-fired power plant in their neighborhood, which was connected to poor health outcomes for residents. Now, the state proposes to convert that very site into a gas-fired power plant to meet the energy demands of data centers. Every year, the pollution from natural gas plants is responsible for approximately 4,500-12,000 early deaths in the U.S., studies show.

“If you mapped all of the existing power plants in South Carolina, they’d follow the old path of one of the foundational pillars of the American economy through South Carolina: plantations and enslaved labor,” Boatwright said. “We’ve seen the repeated pattern of these threats in our community.”

With this boom, tech companies like Google are making huge profits by securing special deals with utility companies.

Google’s head of data center energy, Amanda Peterson Corio, said Google’s energy supply contracts undergo “rigorous review” by utility regulators and are crafted “to ensure that Google covers the utility’s cost to serve us.”

Yet, last year, the company inked a deal in South Carolina to pay less than half the rate that households pay for electricity.

These low rates, combined with tax breaks and state-approved subsidies, are used to lure big tech companies. However, these deals force local families and households to cover the cost of building extra power plants, meaning everyday customers end up footing the bill.

A data center is a combination of massive warehouses packed with rows of servers and high-tech gear that stretch longer than football fields, all humming away to store and manage the digital data we use every day. They’re so massive, for example, that Google’s first South Carolina data center, which opened in Berkeley County in 2009, uses the equivalent electricity of roughly 300,000 homes and the amount of water of at least 9,000 homes. As of 2021, it was also powered by more fossil fuel based energy sources than any of Google’s two dozen other data centers nationwide.

This uneven situation leads to a growing gap between corporate savings and community expenses, with everyday people shouldering the extra burden. Black communities, in particular, tend to face higher utility costs and, as a result, are more likely to have their power shut off for missed payments. Along the East Coast, monthly utility bills are expected to increase as much as $40 to $50, mainly due to data centers.

South Carolina legislators — Democrats and Republicans — have implored the state’s regulators to rethink discounts and other subsidies, but the push has not made waves so far.

“Current residential ratepayers are going to pay a lot, lot more because of data centers that bring almost no employees,” Chip Campsen, a Republican South Carolina state senator, said at a legislative hearing last September. Tech companies must “participate in paying the capital costs for building the generating capacity for these massive users of energy.”

This issue ties into broader government policies aimed at boosting American technological growth and making the United States a leader in artificial intelligence. The Trump administration, for example, has signaled that it might bypass some environmental regulations to speed up projects like data centers and power plants. The new leader of the Environmental Protection Agency, Lee Zeldin, has said making “the United States the Artificial Intelligence capital of the world” will be one of his five guiding pillars, along with making it easier for tech and manufacturing companies to invest in the American economy.

Near Jenkinsville, South Carolina, half-built nuclear reactors — remnants of the long-stalled V.C. Summer project — tower over a Black community where three out of four live in poverty. They stand as a stark reminder of a $9 billion investment that never produced power. Despite customers still footing the bill for this abandoned venture to the tune of multiple utility bill increases, the state-owned utility company Santee Cooper is now inviting proposals to complete one or both units. Supporters argue that reviving the project would add 2,200 megawatts to the grid — enough to power hundreds of thousands of homes — and help meet surging energy demands driven by tech giants. Recent inspections by the state’s Nuclear Advisory Council have deemed the site in excellent condition, bolstering growing legislative support.

Researchers say it would be the first and only nuclear project to restart after being halfway built. Critics caution that history warns against overly ambitious nuclear bets that can lead to decades of delays, spiraling costs, and additional burdens on customers. They contend that immediate, incremental investments in solar power and battery storage could offer a safer, more adaptable path forward rather than reinvesting in a risky long-term gamble. Currently, nuclear energy is about four times more expensive to produce than solar energy.

Last year, the state was granted over $130 million from the Biden administration for solar projects, but the funding is now in limbo under the Trump administration.

The Black-led South Carolina Energy Justice Coalition has spent years advocating for solar and wind energy in rural Black communities. “Every citizen is worthy of that type of energy by virtue of just being a human being,” Shayne Kinloch, the group’s director, said last year.

Along the banks of the Edisto River in the heart of South Carolina, a former coal-fired power plant — closed in 2013 — is poised for a dramatic transformation. Dominion Energy and Santee Cooper plan to convert the site into one of the nation’s largest gas-fired power stations, a move approved by the state’s Public Service Commission. Designed to produce up to four times the energy of the old plant, this project is a central part of efforts to retire remaining coal facilities by 2030 and transition toward a future of “reliable, affordable, and increasingly clean energy,” the companies said.

However, environmental advocates and legal experts warn that this expansion of gas infrastructure may echo a troubling legacy where vulnerable communities bear the brunt of environmental and economic risks. Shifting from coal to gas plants isn’t environmentally or cost-effective, opponents say, because while gas produces slightly less pollution than coal, it still contributes significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. It also comes with high infrastructure and maintenance costs.

This month, the state’s House of Representatives approved legislative changes that would weaken oversight of gas power plants. Joining Republicans, South Carolina’s Legislative Black Caucus Chairwoman Annie McDaniel, a Democrat representing the county home to the nuclear plant, voiced support for the legislation.

McDaniel did not respond to Capital B’s request for comment.

The changes, if passed by the state’s Senate, would allow the groups to bypass rigorous environmental reviews when proposing projects. Supporters claim these measures are necessary to meet rising energy demands from tech-driven growth. Critics argue this could sideline investments in renewable alternatives like solar and battery storage and raise the risk of rising costs, delays, and potential noncompliance with federal pollution standards.

“Instead of investing in more risky energy generation and infrastructure, they should be investing in energy solutions like solar and storage,” Boatwright said, “but utilities are choosing the most expensive and environmentally risky.”

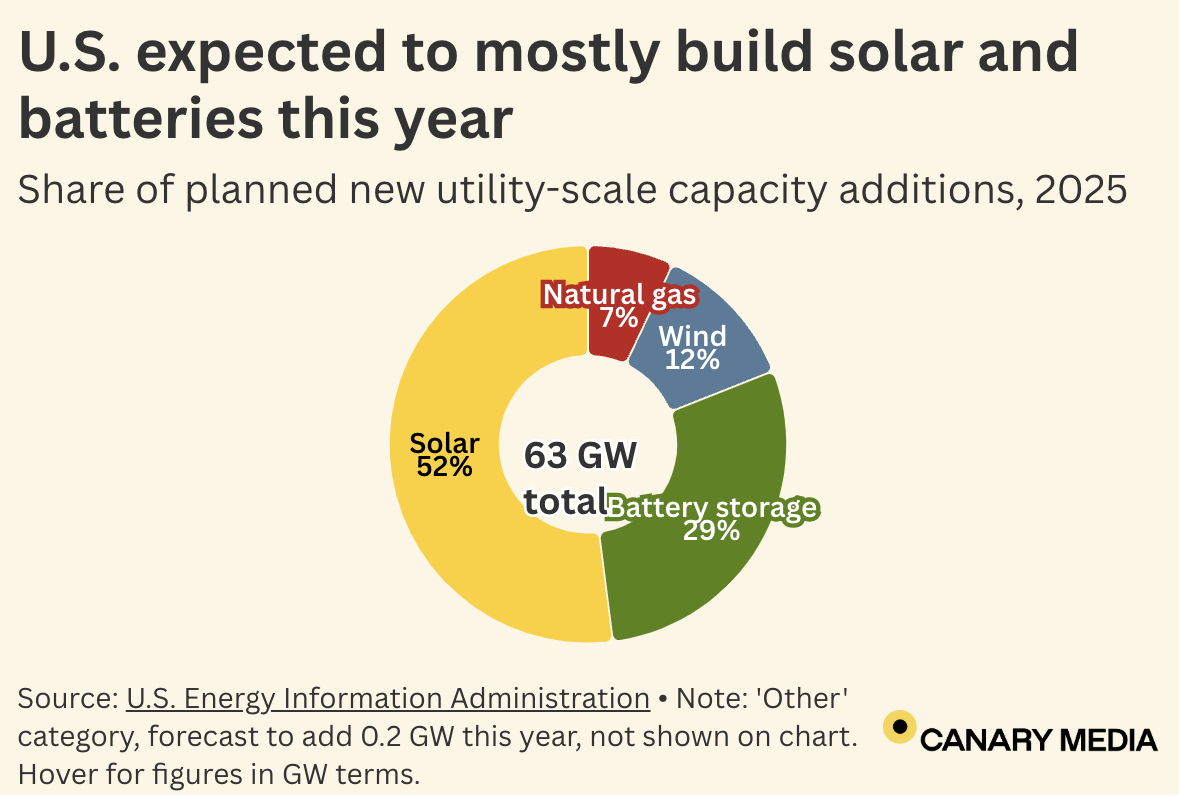

The numbers are in, and clean energy is set to sweep U.S. power plant construction yet again this year.

The U.S. is expected to build 63 gigawatts of power plant capacity this year, more than it has in decades, as new AI computing and domestic manufacturing projects cause a surge in energy demand. At this crucial juncture, plants that don’t burn fossil fuels are set to deliver 93% of all the new capacity joining the U.S. grid in 2025, per new estimates from the federal Energy Information Administration.

The new prediction is no fluke — carbon-free sources delivered nearly all the new capacity last year, too. And the trend was building for years before that.

This year, utility-scale solar is expected to continue its winning streak as the largest source of new electricity generation. More than half of new power plant capacity built this year will be solar, followed by batteries, with 29% of total capacity. That’s a step up for batteries from last year. Meanwhile, solar’s share is forecast to fall, but EIA expects more construction in absolute terms — 32.5 gigawatts compared to 30 last year.

Wind will add 12% of the new capacity, burnished by two major offshore wind projects the EIA still expects to come online despite political headwinds: Massachusetts’ 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind 1 and Rhode Island’s 715-megawatt Revolution Wind. The Trump administration unilaterally halted federal permitting for new offshore wind projects, but these are among the five that were already under construction, with necessary permits in hand.

This dominant showing from clean energy developers leaves natural gas with just 7% of new power capacity. That fossil fuel still leads in total U.S. electricity generation with about 42% of the mix but has entered a multi-year slump in terms of new construction.

The EIA predicts total gas-fired generation — the actual electricity produced — will fall 3% this year while solar generation rises by more than one-third.

This dataset offers a snapshot of where the U.S. power industry is heading — and the direction is toward cleaner, cheaper energy that mainly comes from solar and batteries.

But beyond the climate metrics, these clean power plants are proving vital in meeting the needs of an increasingly power-hungry economy. Data centers, AI hubs, and the domestic manufacturing that grew during the Biden administration all need more electricity. Renewables and batteries are the source of energy that can meet this demand most quickly and cost-effectively, though they still need to work alongside other resources to ensure 24/7 service.

A fast-growing startup is giving Texas homeowners cheap access to unusually large batteries for backup power — and paying for it by maneuvering those same batteries in the state’s ERCOT energy markets.

Base Power launched last May and already has installed more than 1,000 home batteries, around 30 megawatt-hours, in North Austin and the Fort Worth area, CEO Zach Dell told Canary Media recently. The company plans to expand that footprint to 250 megawatt-hours this year, he added.

To make good on that promise, the 80-person startup rolled out service to the Houston area last week. That move had been planned for this summer, but customers in the storm-prone metropolis were calling and emailing to sign up, and a cold snap was bearing down on Texas, testing the grid’s ability to keep pace with winter energy needs.

“We saw what happened in Winter Storm Uri, four years ago, and we want to put a solution in the hands of Texans for situations like that,” Dell said, referring to the widespread grid outages that contributed to hundreds of deaths. “As another cold front sweeps through Texas this week, we felt like pulling up the Houston launch as quickly as possible was the right thing to do.”

If a homeowner in Texas wants backup power, they could buy solar and a battery. But most battery products aren’t large enough to meet the needs of the typical American home — that’s why you see three Tesla Powerwalls lined up in some garages. At that point, the out-of-pocket cost reaches tens of thousands of dollars, unless the buyer grapples with the current state of interest rates and takes out a loan.

Base Power pitches the benefits of whole-home backup power without the massive up-front expenditure. The company designed its own battery for the express purpose of backup power, so each unit packs 25 kilowatt-hours of storage instead of the usual 10 or 15. It can instantly discharge 11.4 kilowatts of power. Some people get two of these side by side for a truly hefty home energy arsenal.

But the customers don’t buy this product: They pay a $495 installation fee and an ongoing monthly fee of $16. They also choose Base Power as their electricity retailer — Texas allows customers to pick who they buy from — and pay 8.5 cents per kilowatt-hour for their general household consumption.

If there’s no such thing as a free lunch, nor is there nearly free backup power. Base Power (and, by extension, its venture backers) fronts this rather hefty bill, on the premise that it can make money not just from customer subscriptions but by bidding the decentralized battery fleet into the ERCOT energy markets. That also lets Base Power charge a lower rate for household electricity than it otherwise would need to.

“We’re a battery developer; we’re an asset owner,” Dell explained. “For us and for the customer, a bigger battery is better.”

In that sense, this company is the newest in a lineage of startups seeking to unlock the multi-layered benefits of distributed energy devices, which both help a local customer and, when harnessed with effective software and amenable market rules, make the overall grid more clean and efficient.

Many startups have gone bankrupt chasing this rosy vision. Base Power aims to avoid their fate by adopting a very old technique in the utility sector: vertical integration.

In order to make its customer-friendly product into a viable business, Dell and company have taken control of every step of their value chain, rather than outsourcing or partnering.

The company designed its own battery hardware, giving it far more capacity than the market-leading home battery systems. Base Power wrote its own software to govern the batteries and operate them as a decentralized fleet bidding into the wholesale markets. And the startup does its own sales, installations, and long-term maintenance.

The corporate strategy, Dell explained, is to create “compounding cost advantage through vertical integration.” If Base Power bought, say, Tesla Powerwalls and resold them to customers, it would have to give Tesla a margin. If it paid outside firms to knock on doors and pitch batteries, those commercial evangelists would also take their cut. Contracting out for installation further dilutes the profits, and so on.

“Because we do all these things, we can take cost out of every part of the system and then pass those savings down to the customer in the form of low prices,” Dell said. “As our returns go up and our cost of capital goes down, our intention is to build the largest and most capital-efficient portfolio of batteries in the country.”

Minimizing cost and reliance on outside parties makes fundamental sense, and yet fledgling startups typically shy away from taking on so much for fear of biting off more than they can chew.

“It’s really hard,” Dell admitted. However, “because it’s so hard, there’s not a lot of people who can do it.”

It’s a business strategy that calls to mind the ancient bristlecone pines that occupy a remote, arid mountaintop between the eastern Sierras and California’s border with Nevada. The trees suffer extremes of heat and cold and thirst and wind, but when they persist, they carve out a niche where few competitors can survive. The oldest bristlecones predate the pyramids of Giza.

The do-it-all approach also distinguishes Base Power from others that are similarly trying to get more batteries into people’s homes.

German company sonnen has been working on this challenge for over a decade and operates a vast network of home batteries in Germany that make money in power markets there. In the U.S., the company partners with solar companies and sometimes with real estate developers to sell its batteries. Sonnen launched a no-money-down battery offering in Texas with a company called Solrite, which had put equipment in more than 1,000 homes as of January, a similar volume to what Base Power has installed.

Neither sonnen nor Solrite are retail electricity providers in Texas, though, so they need to pair up with companies that buy and sell power and can monetize the batteries’ ability to arbitrage. The Solrite deal requires people to sign up for 25 years and buy out any remaining value if they want to quit before the quarter-century mark. Base Power, in contrast, asks customers to commit to a three-year retail contract, and the cancellation fee is $500, to cover removing the battery system.

Other climatetech-savvy retailers offer special deals for people who buy their own batteries. Great Britain’s Octopus Energy has entered the ERCOT market and offers modest monthly credits per kilowatt-hour of storage capacity if residents let the company manage their home batteries. Octopus uses its software to shift consumption to times with abundant renewable generation, thereby lowering the cost of serving those households.

Startup David Energy offers retail plans in which the company optimizes customers’ battery usage to minimize their overall electricity bill. Tesla itself opened a Texas electricity retailer subsidiary that pays customers a fixed credit of $400 per year for each Powerwall pack that they allow to discharge to the grid, up to three Powerwalls.

Those providers still need customers to front the money or take out a loan to install their own batteries, which constrains how quickly battery adoption can grow. On the other hand, that model means those companies can focus on honing their energy software and trading strategy and don’t have to spend millions of dollars to install and own batteries that might one day pay for themselves.

Base Power pays for its buildout with a mix of equity, debt, and tax credits, Dell noted. Investors funded an $8 million seed raise led by Thrive Capital and a $60 million Series A led by Valor Equity Partners. As for making money, Base Power uses the batteries to arbitrage energy in the ERCOT market from the renewables-filled times of plenty to the valuable hours of scarce supply. The company is currently undergoing qualification to bid ancillary services, a more complex suite of market offerings that maintain the quality and reliability of the grid.

This is the fourth and final article in our series “Boon or bane: What will data centers do to the grid?”

Tom Wilson is aware that the explosive growth of data centers could make electricity costlier and dirtier. As a principal technical executive at the Electric Power Research Institute, the premier U.S. utility research organization, he’s studied the risks himself.

But he also thinks conversations about the problem tend to miss a key point. Data centers could also make the grid cleaner and cheaper by embracing a simple concept: flexibility.

“Data centers are not just load — they can also be grid assets,” he said. Turning that proposition into reality is the goal of his most recent project, DCFlex, a collaborative effort to get data centers to “support the electric grid, enable better asset utilization, and support the clean energy transition.”

DCFlex is short for “data center flexibility,” a term that encompasses all the ways that these sprawling campuses and buildings full of servers, cooling equipment, power-control systems, backup generators, and batteries can reduce or shift their power use.

Since its October launch, DCFlex has grown from 15 to 37 funding participants. On the data-center side are tech “hyperscalers” like Google, Meta, and Microsoft; major data center developers like Compass and QTS; and AI computing and power equipment suppliers like Nvidia and Schneider Electric.

On the grid side are utilities such as Duke Energy, Pacific Gas & Electric, Portland General Electric, and Southern Company; power plant owners like Constellation Energy, NRG Energy, and Vistra; and five of the continent’s seven grid operators, which manage energy markets serving electricity to two-thirds of the U.S. population.

The range of participants reflects the broad interest in solving the pressing challenge of powering the data centers being proposed around the country without driving up grid costs and emissions.

That won’t be easy. From Virginia’s “Data Center Alley” to emerging hot spots in Arizona, Georgia, Indiana, Ohio, and beyond, utilities are being inundated with demands for round-the-clock power from data center projects that can add the equivalent of a small city’s electricity consumption within a few years. Meanwhile, it usually takes four or five years to connect new power plants to the grid.

Flexibility could make a big difference, however, said Tom Wilson, who’s worked on climate and energy issues for more than four decades, including advising projects at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford University and serving at the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy during the Biden administration.

That’s because the impacts of massive new utility customers like data centers are tied not just to how much power they need but specifically to when they need it.

Utilities live and die by the few hours per year when demand for electricity peaks — usually during the hottest and coldest days. By refraining from using grid power during those peak hours, new data centers could significantly reduce their impact on utility costs and carbon emissions.

If data centers and other big electricity customers committed to curtailing their power use during peak hours, it could unlock tens of gigawatts of “spare” capacity on U.S. grids, according to a recent analysis from Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Energy, Environment & Sustainability.

Realizing that spare capacity will be challenging, though. For starters, every new large power customer would have to agree not to use grid power during key hours of the year, which is far from a realistic expectation today. What’s more, utilities would need some serious proof that those big customers can actually follow through with promises to not use power during those peak times before letting them connect, because broken promises in this case could lead to overloaded grids or forced blackouts.

And flexibility can’t solve all the power problems that massive data center expansion could cause.

In a December report, consultancy Grid Strategies found that key data center markets are driving an unprecedented fivefold increase in the amount of new power demand that U.S. utilities and grid operators forecast over the next half decade or so. While that analysis “really focused on the peak demand forecast,” the sheer amount of power needed over the course of a year is “potentially just as big of a story,” said John Wilson, Grid Strategies’ vice president.

Still, for utilities struggling to plan and build the generation and grid infrastructure needed to support data centers, flexibility is worth exploring. That’s because data centers could make their operations flexible a lot faster than utilities can expand power grids and build power plants.

It typically takes seven to 10 years to build high-voltage transmission lines and four to five years to build a gas-fired power plant — “even in Texas,” Tom Wilson pointed out. The concept of relying on big customers to avoid using power instead of building all that infrastructure is just starting to take hold in utility planning, but it could play a major role in managing the surge in power demand.

Flexible data centers may also be able to secure space on capacity-constrained grids more quickly than inflexible competitors, Tom Wilson said. A U.S. Department of Energy report released last year included interviews with dozens of utilities, and one key takeaway was that “electricity providers often can accommodate the energy and capacity requests of a data center for (say) 350 days but need to find a win-win solution for the remaining 15 days.”

“If you have two projects in the queue, and one says they can be flexible and the other says they can’t be flexible, and they’re about the same size, then the one that can be flexible is more likely to be successful,” Tom Wilson said.

That’s not lost on Brian Janous, cofounder of Cloverleaf Infrastructure, which develops what the company describes as “clean-powered, ready-to-build sites for the largest electric loads,” mainly data centers.

“You need to understand, when a utility says, ‘I can’t get you power,’ what they mean is, ‘There are certain hours of the day I can’t get you power,’” he said. The data center industry “lacks visibility into this, which is kind of shocking,” given that data center flexibility is nothing new.

In fact, back in 2016, when he worked as energy strategy director at Microsoft, Janous helped structure a deal for a data center in Cheyenne, Wyoming, to use fossil-gas-fired backup generators to reduce peak grid stress for utility Black Hills Energy. That promise, combined with Microsoft’s agreement to purchase nearly 240 megawatts of wind power, got that deal over the line.

Janous thinks many utilities are eager for similar propositions today. One unnamed utility executive told him recently that the backlog for connecting large data centers to its grid is now at least five years. “I asked, ‘What if the data center could be dispatchable?” And he said, ‘Oh, we could connect them tomorrow. But nobody’s asking me that.’”

Getting utilities and data centers together to ask those kinds of questions is what DCFlex is all about. Project partners are now developing five to 10 demonstration projects, Tom Wilson said, none of which have been announced. But he described the scope of work as ranging from the development stage to “existing sites that are ready to roll.”

As for how these projects will help the grid, he laid out two broad methods: They’ll use on-site power generation or storage to replace what they’d otherwise pull from the grid, or they’ll use less electricity during peak hours.

Janous thinks on-site generation is the simpler approach. To some extent, it’s already happening today but typically with dirty diesel generators. Janous, Tom Wilson, and other experts say these diesel generators are not a viable option for hyperscalers, however. They’re simply too dirty and too expensive to rely on, except during grid outages or other dire situations.

Biodiesel and renewable diesel could work for some smaller data centers, Tom Wilson said. But it’s not yet clear whether air-quality rules would permit generators burning those fuels to run during nonemergencies. Nor are the economics viable for larger-scale data centers, he said.

Fossil-gas-fired backup generators like those Microsoft used in Cheyenne are another option — albeit one that still pollutes the local air and warms the planet. Still, a growing number of data center developers are looking to use them as a workaround to grid constraints. “We’re in the process of developing sites in many parts of the country,” Janous said. “Every one of them has access to natural gas.”

It would be a problem for the planet — and for meeting the climate goals major tech companies have committed to — if data centers planned to use fossil gas for a majority of their power. But if relied on sparingly and strategically, this choice might be less harmful than the alternatives: If a data center burns fossil gas just to power itself during grid peaks, that might reduce pressure on utilities to keep old coal-fired power plants open or to build much larger gas-fired plants that would lock in emissions for decades.

Other gas-fueled options for on-site power might be less damaging to the climate — although this remains a hotly debated topic. Microgrid developer Enchanted Rock plans to install gas generators at a Microsoft data center in San Jose, California, which will burn regular fossil gas but will offset that usage by purchasing an equivalent amount of “renewable natural gas” — methane captured from rotting food waste. It claims this will make the project emissions-free.

And utility American Electric Power has signed an agreement to buy 1 gigawatt of fuel cells from Bloom Energy, which it plans to install at data centers. The firm’s fuel cells still emit carbon dioxide, but they avoid the harmful nitrous oxides caused by burning gas.

Batteries are another option — and the one that has the greatest potential to be clean. Most data centers have some batteries on-site to help computers ride through grid disruptions until backup generators can turn on, but relying on batteries for backup power and to provide grid support is a far more complex and costly endeavor.

“There are all kinds of trade-offs in terms of reliability, in terms of emissions, in terms of cost, in terms of the physical footprint,” Tom Wilson said. “In a storm situation that brought the grid down, you’d want something that can be dependable.”

A small but growing number of hyperscalers are looking to batteries for both backup power and grid flexibility. Google’s battery-backed data center in Belgium is one example.

“We built out battery storage as a way to displace part of our diesel gensets, to provide grid services, and to provide relief during times of extreme grid stress when we needed backup,” said Amanda Peterson Corio, Google’s global head of data center energy.

In the U.S., a Department of Energy grant is supporting a battery installation at an Iron Mountain data center in Virginia that’s meant to test the potential to store clean power for backup and grid-support uses.

It’s one of a number of DOE programs launched under the Biden administration whose purpose is to explore ways that “battery energy storage systems can provide similar levels of reliability, and without a lot of the challenges that diesel gensets or other backup power sources have,” Avi Shultz, director of the DOE’s Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office, said in an October interview.

The other big idea for making data centers flexible focuses not on the power they can generate and store but on the power they use, Shultz said.

“Demand response” is the utility industry term for the practice of throttling power use during times of peak grid stress, or of shifting that power use to other times when the grid can handle it better, in exchange for payments from utilities or revenues in energy markets.

Historically, data centers haven’t been interested in standard demand-response programs and markets. The value of what they do with that electricity is just too high compared with the potential rewards.

But if a data center’s participation in a demand-response program is the difference between it getting a grid connection or not, the programs become a lot more appealing.

Shultz highlighted two key data center tasks that are particularly ripe for load flexibility.

The first is “cooling loads and facility energy demand,” he said. Data centers use enormous amounts of electricity to keep their servers and computing equipment from overheating, and quite a bit of that energy is lost in the process of converting from high-voltage grid power to the low-voltage direct current that computing equipment uses.