A handful of school buses in northern Illinois will soon have a new summer job.

ComEd is the latest utility to explore whether electric school buses could help manage the grid when school is out of session and air conditioners are humming.

Under such vehicle-to-grid, or V2G, arrangements, electric school buses charge up at night when power is cheap and plentiful, then discharge electricity to the grid when local power demand is high. This infusion can alleviate the need to fire up natural gas peaker plants, buy expensive power on the market, or even build new power plants.

The buses basically act as batteries attached to the grid, in a win-win situation where school districts are paid for the service and utilities get power that is cheaper and possibly cleaner than what they could otherwise acquire during peak hours.

V2G projects are still in nascent and pilot-project stages, and significant challenges exist. The grid needs to communicate seamlessly with the bus charging station, and operators must make sure bus batteries are ready when needed and that the grid isn’t overloaded by local bursts of energy. Standards and certifications for V2G technology and practice are also still in early stages.

“It takes a lot of effort to do those communications properly,” said Greggory Kresge, senior manager for utility engagement and transportation electrification at the World Resources Institute, a research and advocacy nonprofit focused on environmental and economic issues. “You have communication about speed, power level, how many kilowatts, how fast, what’s the duration — all these different packets of information going back and forth. It’s a fragile ecosystem. If one of those communication links breaks, it doesn’t function.”

ComEd has proposed a pilot project launching this spring and running through 2025 in partnership with the San Diego-based company Nuvve, which also has led V2G pilots in California, Delaware, and New York as well as in Europe and Asia. While the ComEd pilot will only involve four electric school buses in three different northern Illinois school districts, it could pave the way for widespread V2G in an area with hot summers, air pollution problems, and lots of students.

“The main idea is to look at this from a technology-demonstration standpoint,” said Sri Raghavan (Raghav) Kothandaraman, ComEd manager of emerging technology, smart grid, and innovation. “How does the charger work in connection with the bus? How does it work with the grid? How do we send commands to these chargers to be able to discharge during particular times? We’re trying to look at it from a win-win-win scenario for school districts and [electric bus] manufacturers as well as the utility.”

Kothandaraman said he could not say whether the buses are already owned by the districts or would be provided by ComEd. Nuvve CEO and cofounder Gregory Poilasne said the vehicles would be made by Blue Bird, one of the country’s leading electric-bus manufacturers.

Electric school buses cost about three times as much upfront as traditional diesel school buses, though the savings on fuel and maintenance can make the total cost of ownership lower over time.

School districts have had access to electric school bus funding from the Volkswagen emissions-cheating settlement and the Biden administration’s $5 billion Clean School Bus Program, but the federal initiative ends next year. Clean energy advocates say V2G programs could provide a new revenue source that makes electric school buses more financially viable for districts while slashing the air pollution and noise that students and drivers are exposed to with diesel buses.

A 2022 WRI report counted at least 15 utilities across 14 states with electric school bus V2G programs. Kresge noted that school districts can earn high payments for power from their buses during peak demand or “emergency load reduction program” times designated by utilities. In California pilot programs, utilities pay $2 per kilowatt-hour during emergency load reduction periods, whereas market prices in the state hover around 30 cents per kilowatt-hour.

Along with feeding the grid, electric school buses can act as behind-the-meter batteries that give schools emergency power during blackouts, Kresge said. In California, they can also power school buildings when utilities shut down transmission lines because of wildfire risk.

“We’re really looking at these buses as resiliency assets, for potential emergency backup power,” said Kresge. “You’re not powering an entire school but just the gymnasium or cafeteria,” which could serve as a community shelter during a disaster, he said. “If a tornado comes through, kids are not going to school, and the buses are available unless they got picked up and moved by the tornado.”

ComEd’s pilot is part of its Beneficial Electrification program, wherein state regulators required the utility to invest in vehicle electrification, including spending $5 million a year for three years on pilots to explore the most efficient and equitable ways to do so.

Kothandaraman said the participating school districts will likely be announced in the coming weeks after contracts are finalized. ComEd’s service territory includes Chicago as well as surrounding suburbs and several other cities. Last year, Chicago announced federal funding for up to 50 electric school buses for the district.

Poilasne noted that grid battery storage and innovations like V2G are increasingly necessary in part because of the extra demand that more and more electric vehicles will put on grids.

“We’re in an environment where for the first time in 25 years, the load on the grid is increasing, driven by heat pumps, data centers, [and] EVs,” Poilasne said. “It’s not just load increasing; it’s the volatility of these loads. The generation is volatile; the load is volatile. You need to design a system for peaks” that last a short time but can skyrocket electricity costs.

“The utilities love to upgrade infrastructure. That’s how they’re making money, but in this environment, they can’t just upgrade the system because the cost would be prohibitive,” Poilasne added. “It’s all about keeping the cost of energy equitable in this fast-changing environment.”

A school district participating in V2G has to install bidirectional charging stations, which are significantly more expensive than traditional ones. However, utilities may be willing to subsidize this infrastructure. Utilities additionally need to be able to handle two-way flow of power on their grids. This also happens when rooftop or other distributed solar panels send power to the grid, so utilities in solar-heavy states are especially prepared for this dynamic.

A third-party company like Nuvve typically provides the software and manages the charging stations for a school district, whether it is doing V2G or not.

“Vehicle readiness is the number one priority,” said Poilasne. “There’s a lot of work on forecasting when the EV will be there, when it will come back, what’s the level of charge when it comes back.”

WRI hosts a utility working group on V2G programs and advises that utilities structure rates specifically to make such initiatives more attractive for school districts. WRI also recommends school bus V2G programs prioritize communities with disadvantaged populations facing disproportionate air pollution, since electric buses can directly improve the air students breathe each day.

Even though school bus V2G programs are still small, Kresge thinks they will become commonplace and financially beneficial in coming years.

“We’ve been recommending if you have the opportunity to buy bidirectional-capable bus chargers, even if you’re not moving forward with V2G right at this moment, you should go ahead and get it,” Kresge said. “We’re anticipating that we’re going to see huge advancements and a lot more opportunity within the next four to five years on the technology side that will make [V2G] more scalable, more deployable. These programs are coming, so don’t hold back.”

This is the second article in our series “Boon or bane: What will data centers do to the grid?”

There’s no question that data centers are about to cause U.S. electricity demand to spike. What remains unclear is by how much.

Right now, there are few credible answers. Just a lot of uncertainty — and “a lot of hype,” according to Jonathan Koomey, an expert on the relationship between computing and energy use. (Koomey has even had a general rule about the subject named after him.) This lack of clarity around data center power requires that utilities, regulators, and policymakers take care when making choices.

Utilities in major data center markets are under pressure to spend billions of dollars on infrastructure to serve surging electricity demand. The problem, Koomey said, is that many of these utilities don’t really know which data centers will actually get built and where — or how much electricity they’ll end up needing. Rushing into these decisions without this information could be a recipe for disaster, both for utility customers and the climate.

Those worries are outlined in a recent report co-authored by Koomey along with Tanya Das, director of AI and energy technology policy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, and Zachary Schmidt, a senior researcher at Koomey Analytics. The goal, they write, “is not to dismiss concerns” about rising electricity demand. Rather, they urge utilities, regulators, policymakers, and investors to “investigate claims of rapid new electricity demand growth” using “the latest and most accurate data and models.”

Several uncertainties make it hard for utilities to plan new power plants or grid infrastructure to serve these data centers, most of which are meant to power the AI ambitions of major tech firms.

AI could, for example, become vastly more energy-efficient in the coming years. As evidence, the report points to the announcement from Chinese firm DeepSeek that it replicated the performance of leading U.S.-based AI systems at a fraction of the cost and energy consumption. The news sparked a steep sell-off in tech and energy stocks that had been buoyed throughout 2024 on expectations of AI growth.

It’s also hard to figure out whose data is trustworthy.

Companies like Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, OpenAI, Oracle, and xAI each have estimates of how much their demand will balloon as they vie for AI leadership. Analysts also have forecasts, but those vary widely based on their assumptions about factors ranging from future computing efficiency to manufacturing capacity for AI chips and servers. Meanwhile, utility data is muddled by the fact that data center developers often surreptitiously apply for interconnection in several areas at once to find the best deal.

These uncertainties make it nearly impossible for utilities to gauge the reality of the situation, and yet many are rushing to expand their fleets of fossil-fuel power plants anyway. Nationwide, utilities are planning to build or extend the life of nearly 20 gigawatts’ worth of gas plants as well as delaying retirements of aging coal plants.

If utilities build new power plants to serve proposed data centers that never materialize, other utility customers, from small businesses to households, will be left paying for that infrastructure. And utilities will have spent billions in ratepayer funds to construct those unnecessary power plants, which will emit planet-warming greenhouse gases for years to come, undermining climate goals.

“People make consequential mistakes when they don’t understand what’s going on,” Koomey said.

Some utilities and states are moving to improve the predictability of data center demand where they can. The more reliable the demand data, the more likely that utilities will build only the infrastructure that’s needed.

In recent years, the country’s data center hot spots have become a “wild west,” said Allison Clements, who served on the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission from 2020 to 2024. “There’s no kind of source of truth in any one of these clusters on how much power is ultimately going to be needed,” she said during a November webinar on U.S. transmission grid challenges, hosted by trade group Americans for a Clean Energy Grid. “The utilities are kind of blown away by the numbers.”

A December report from consultancy Grid Strategies tracked enormous load-forecast growth in data center hot spots, from northern Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” the world’s densest data center hub, to newer boom markets in Georgia and Texas.

Koomey highlighted one big challenge facing utilities and regulators trying to interpret these forecasts: the significant number of duplicate proposals they contain.

“The data center people are shopping these projects around, and maybe they approach five or more utilities. They’re only going to build one data center,” he explained. “But if all five utilities think that interest is going to lead to a data center, they’re going to build way more capacity than is needed.”

It’s hard to sort out where this “shopping” is happening. Tech companies and data center developers are secretive about these scouting expeditions, and utilities don’t share them with one another or the public at large. National or regional tracking could help, but it doesn’t exist in a publicly available form, Koomey said.

To make things more complicated, local forecasts are also flooded with speculative interconnection requests from developers with land and access to grid power, with or without a solid partnership or agreement in place.

“There isn’t enough power to provide to all of those facilities. But it’s a bit of a gold rush right now,” said Mario Sawaya, a vice president and the global head of data centers and technology at AECOM, a global engineering and construction firm that works with data center developers.

That puts utilities in a tough position. They can overbuild expensive energy infrastructure and risk whiffing on climate goals while burdening customers with unnecessary costs, or underbuild and miss out on a once-in-a-lifetime economic opportunity for them and for their community.

In the face of these risks, some utilities are trying to get better at separating viable projects from speculative ones, a necessity for dealing with the onslaught of new demand.

Utilities and regulators are used to planning for housing developments, factories, and other new electricity customers that take several years to move from concept to reality. A data center using the equivalent of a small city’s power supply can be built in about a year. Meanwhile, major transmission grid projects can take a decade or more to complete, and large power plants take three to five years to move through permitting, approval, procurement, and construction.

Given the mismatch in timescales, “the solution is talking to each other early enough before it becomes a crisis,” said Michelle Blaise, AECOM’s senior vice president of global grid modernization. “Right now we’re managing crises.”

Koomey, Das, and Schmidt highlight work underway on this front in their February report: “Utilities are collecting better data, tightening criteria about how to ‘count’ projects in the pipeline, and assigning probabilities to projects at different stages of development. These changes are welcome and should help reduce uncertainty in forecasts going forward.”

Some utilities are still failing to better screen their load forecasts, however — and tech giants with robust clean energy goals such as Amazon, Google, and Microsoft are speaking up about it. Last year, Microsoft challenged Georgia Power on the grounds that the utility’s approach is “potentially leading to over-forecasting near-term load” and “procuring excessive, carbon-intensive generation” to handle it, partly by including “projects that are still undecided on location.” Microsoft contrasted Georgia Power’s approach to other utilities’ policies of basing forecasts on “known projects that have made various levels of financial commitment.”

Utilities also have incentives to inflate load forecasts. In most parts of the country, they earn guaranteed profits for money spent on power plants, grid expansions, and other capital infrastructure.

As a matter of fact, many utilities have routinely over-forecasted load growth during the past decade, when actual electricity demand has remained flat or increased only modestly. But today’s data center boom represents a different kind of problem, Blaise said — utilities “could build the infrastructure, but not as fast as data centers need it.”

In the face of this gap between what’s being demanded of them and what can be built in time, some utilities are requiring that data centers and other large new customers prove they’re serious by putting skin in the game.

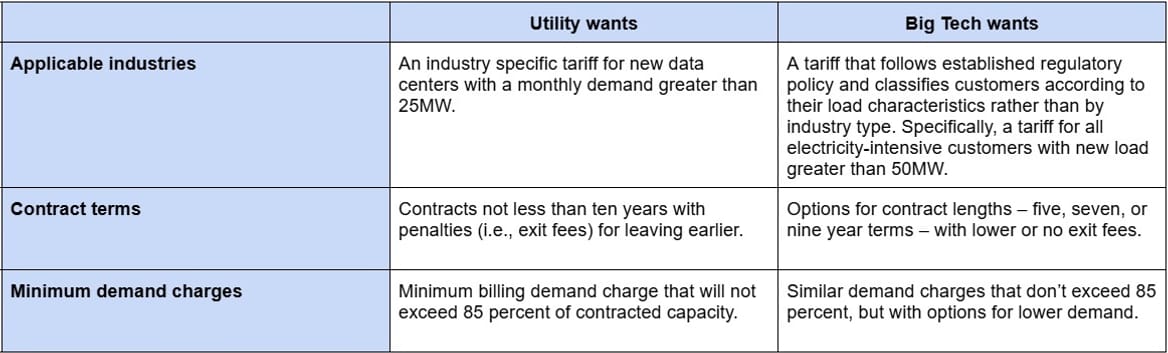

The most prominent efforts on this front are at utility American Electric Power. Over the past year, AEP utilities serving Ohio as well as Indiana and Michigan have proposed new tariffs — rules and rates for utility customers — to deal with the billions of dollars of data center investments now flooding into those states.

AEP Ohio and state regulators proposed a settlement agreement in October that would require data centers to commit to 12-year agreements to “pay for a minimum of 85% of the energy they say they need each month — even if they use less.” The proposed tariff would also require prospective data center projects to provide more financial disclosures and to pay an exit fee if they back out or fail to meet their commitments.

A counterproposal filed in October by Google, Meta, Microsoft, and other groups would also set minimum power payments but loosen some other requirements.

AECOM’s Sawaya and Katrina Lewis, the company’s vice president and energy advisory director, laid out the differences between the competing proposals in a December opinion piece.

“On the one hand, the utility is seeking to protect other customer classes and reduce unnecessary investment by ensuring longer term commitments,” they wrote. “While on the other, Big Tech is looking to establish tariffs that drive innovation and growth through the appropriate grid investments without individual industries being singled out.”

AEP utility Indiana Michigan Power (I&M) has made more progress than AEP Ohio threading this needle. In November, it reached an agreement with parties including consumer advocates and Amazon Web Services, Google, Microsoft, and the trade group Data Center Coalition. That plan was approved by Indiana utility regulators last week.

A number of nitty-gritty details distinguish that deal from the disputes AEP Ohio is still wrangling over. One key difference is that I&M’s plan would apply to all large power-using customers, not just data centers.

But AECOM’s Lewis noted that data centers aren’t the only stakeholders to consider in making such a plan. Economic-development entities, city and county governments, consumer advocates, environmental groups, and other large energy customers all have their own opinions. Negotiations like those in Ohio and Indiana “will have to happen around the country,” she said. “They’re likely to be messy at first.”

That’s a good description of the various debates happening across the U.S. In Georgia, utility regulators last month approved a new rule requiring data centers of 100 megawatts or larger to pay rates that would include some costs of the grid investments needed to support those centers. But business groups oppose legislative efforts to claw back state sales tax breaks for data centers, including a bill passed last year that Republican Gov. Brian Kemp vetoed.

In Virginia, lawmakers have proposed a raft of bills to regulate data center development, and regulators have launched an investigation into the “issues and risks for electric utilities and their customers.” But Republican Gov. Glenn Youngkin has pledged to fight state government efforts to restrain data center growth, as have lawmakers in counties eager for the economic benefits they can bring.

But eventually, Koomey said, these policy debates will have to reckon with a fundamental question about data center expansion: “Who’s going to pay for this? Today the data centers are getting subsidies from the states and the utilities and from their customers’ rates. But at the end of the day, nobody should be paying for this except the data centers.”

Not all data centers bring the same economic — or social — benefits. Policies aimed at forcing developers to prove their bona fides may also need to consider what those data centers do with their power.

Take crypto mining, a business that uses electricity for number-guessing computations to claim ownership of units of digital worth. Department of Energy data suggests that crypto mining represents 0.6% to 2.3% of U.S. electricity consumption, and researchers say global power use for mining bitcoin, the original and most widely traded cryptocurrency, may equal that of countries such as Poland and Argentina.

Crypto mining operations are also risky customers. They can be built as rapidly as developers can connect containers full of servers to the grid and can be removed just as quickly if cheaper power draws them elsewhere.

This puts utilities and regulators in an uncomfortable position, said Abe Silverman, an attorney, energy consultant, and research scholar at Johns Hopkins University who has held senior policy positions at state and federal energy regulators and was a former executive at utility NRG Energy.

“Nobody wants to be seen as the electricity nanny — ‘You get electricity, you don’t,’” he said. At the same time, “we have to be careful about saying utilities have to serve all customers without taking a step back and asking, is that really true?”

Taking aim at individual customer classes is legally tricky.

In North Dakota, member-owned utility Basin Electric Cooperative asked the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for permission to charge crypto miners more than other large customers to reduce the risk that gigawatts of new “highly speculative” crypto load could fail to materialize. Crypto operators protested, and FERC denied the request in August, saying that the co-op had failed to justify the change but adding that it was “sympathetic” to the co-op’s plight.

Silverman noted that AEP Ohio’s proposed tariff also sets more stringent collateral requirements on crypto miners than on other data centers. That has drawn opposition from the Ohio Blockchain Council, a crypto trade group, which joined tech companies in the counterproposal to the proposed tariff.

It’s likely that the industry, boosted by its influence with the crypto-friendly Trump administration, will challenge these kinds of policies elsewhere.

Then there’s AI, the primary cause of the dramatic escalation of data center load forecasts over the past two years. In their report, Koomey, Das, and Schmidt take particular aim at forecasts from “influential management consulting and investment advising firms,” which, in Koomey’s view, have failed to consider the physical and financial limitations to unchecked AI expansion.

Such forecasts include those from McKinsey, which has predicted trillions of dollars of near-term economic gains from AI, and from Boston Consulting Group, which proposes that data centers could use as much power as two-thirds of all U.S. households by 2030.

But these forecasts rely on “taking some recent growth rate and extrapolating it into the future. That can be accurate, but it’s often not,” Koomey said. These consultancies also make money selling services to companies, which incentivizes them to inflate future prospects to drum up business. “You get attention when you make aggressive forecasts,” he said.

Good forecasts also must consider hard limits to growth. Koomey helped research December’s “2024 United States Data Center Energy Usage Report” from DOE’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which used real-world data on shipments and orders of the graphical processing units (GPUs) used by AI operations today, as well as forecasts of how much more energy-efficient those GPUs could become.

That forecast found data centers are likely to use from 6.7% to 12% of total U.S. electricity by 2028, up from about 4.4% today.

To be clear, those numbers contain an enormous range of uncertainty, and nationwide estimates don’t help individual utilities or regulators figure out what may or may not get built in their territories. Still, “we think this is a pretty reliable estimate of what energy demand growth is going to look like from the sector,” said Avi Shultz, director of DOE’s Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office. “Even at the low end of what we expect, we think this is very real.”

Koomey remains skeptical of many current high forecasts, however. For one, he fears they may be discounting the potential for AI data centers to become far more energy-efficient as processors improve — something that has happened reliably throughout the history of computing. Similar mistakes informed wild overestimates of how much power the internet was going to consume back in the 1990s, he noted.

“This all happened during the dot-com era,” when “I was debunking this nonsense that IT [information technology] would be using half of the electricity in 10 years.” Instead, data centers were using only between 1% and 2% of U.S. electricity as of 2020 or so, he said. The DeepSeek news indicates that AI may be in the midst of its own iterative computing-efficiency improvement cycle that will upend current forecasts.

Speaking of the dot-com era, there’s another key factor that today’s load growth projections fail to take into account — the chance that the current AI boom could end up a bust. A growing number of industry experts question whether today’s generative AI applications can really earn back the hundreds of billions of dollars that tech giants are pouring into them. Even Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella spoke last week about an “overbuild” of AI systems.

“Over the next several years alone, we’re going to spend over a trillion dollars developing AI,” Jim Covello, head of stock research at investment firm Goldman Sachs, said in a discussion last year with Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor and Nobel Prize–winning economist Daron Acemoglu. “What trillion-dollar problem is AI going to solve?”

In part 3 of this series, Canary Media reports on how to build data centers that won’t make the grid dirtier.

A number of Connecticut cities and towns want to secure more clean electricity for residents using a program that has already saved millions of dollars for consumers in other states.

Community choice aggregation allows cities and towns — or, in some cases, multiple municipalities working together — to negotiate with electricity suppliers on behalf of their residents. The goal is to achieve lower rates than those offered by utilities, often with a higher percentage of renewable energy in the mix.

“Municipalities can play a bigger role in using less electricity, using it more efficiently, and reducing the cost,” said Peter Millman, vice president of People’s Action for Clean Energy, a Connecticut nonprofit that supports community choice aggregation. “I hate to see an opportunity wasted.”

Nationally, community choice aggregation, also known as municipal aggregation, is authorized by ten states, including Northeast neighbors Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, and Rhode Island. Connecticut could become the eleventh: The state legislature is now considering a bill, HB 6928, that would allow municipalities to create these programs. The measure has wide support from environmental groups and municipal leaders.

Data suggest there are opportunities for meaningful savings. In Massachusetts, 225 of the state’s 351 cities and towns had approved municipal aggregation programs as of July 2024, and many include a higher percentage of renewable energy than required by law. In one group of communities, households realized an average of $200 to $237 in annual savings while receiving electricity with 5% to 11% more renewable power content than state requirements, according to an analysis from the Green Energy Consumers Alliance, a nonprofit that helps municipalities create aggregation programs.

“History shows that when a community aggregates consumers for the supplier side, good things happen,” said Larry Chretien, executive director of the organization. “It’s a fallacy that you can’t have greener power without paying more.”

Connecticut’s version of aggregation could be particularly ambitious, following a model used in California and New Hampshire. This approach allows cities and towns to choose between a basic aggregation program, in which a hired energy broker negotiates for electricity on behalf of residents, and a system in which multiple municipalities band together to form a larger aggregator that could handle the process of procuring power itself.

The multi-community approach allows these aggregation groups to retain the revenues that would have gone to an outside broker and use these reserve funds to develop and manage their own programs aimed at producing renewable energy, supporting energy efficiency, or reducing demand. In its first year, New Hampshire’s aggregation program saved ratepayers in participating communities about $14 million and created revenue of $10 million for reinvestment.

In California, this strategy has helped fund dozens of programs including battery rebates, electric vehicle charging infrastructure, and discounts on solar power for low-income households.

Some skeptics of community choice aggregation have raised concerns about Connecticut’s proposed model, which would make a city or town’s negotiated rate the default for residents but allow them to opt out if they’d rather stick with utility service or an alternate supplier. Consumers, they say, should not be placed in a new program without choosing to make the move.

Supporters, however, argue that the successes in states where municipal aggregation has already been deployed demonstrate the model works with little risk to consumers.

“The opt-in model simply doesn’t work,” Millman said at a legislative committee hearing last week. “If these aggregations were not meeting or beating utility rates most of the time, there would be lots and lots of defections — and there are not.”

A Michigan nuclear plant is looking to make history not once but twice over: First by restarting a reactor shuttered in 2022 and second with newly solidified plans to build the nation’s first small modular reactors.

Holtec International — the nuclear company best known for decommissioning shuttered plants and manufacturing the canisters that store spent fuel — bought the Palisades nuclear plant on the southeastern shore of Lake Michigan a month after utility giant Entergy took the financially troubled single-reactor facility offline.

Last year, the Department of Energy’s Loan Programs Office finalized a deal to give Holtec $1.52 billion to bring the 55-year-old, 800-megawatt pressurized water reactor back online. The company wants to plug the facility back into the grid by the end of this year.

Now Holtec plans to nearly double the electricity output from Palisades by building two of its own small modular reactors, or SMRs, at the site.

On Tuesday, top executives gathered at the facility in Covert Township, Michigan, to unveil blueprints for adding a pair of its proprietary SMR-300s and announce Hyundai Engineering and Construction Co. — the South Korean firm already working with the Florida-based Holtec to develop its 300-MW units internationally — as its partner in the debut U.S. project. Completing the reactor would be a first not just for the country but the company. While Holtec has disassembled reactors, it has yet to build one, much less its own design.

“If we can’t do it, I don’t know who else is going to do it,” Rick Springman, the president of Holtec’s Global Clean Energy Opportunities division, told Canary Media ahead of the event. “I really think we can be the horse America can ride to a clean-energy future and to enable AI and everything else we want to do in this global competition.”

First, Holtec will need the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s approval of its reactor design.

So far, the U.S. federal regulator has only approved one SMR, Oregon-based NuScale Power’s 50 MW unit. The first plant designed around NuScale’s reactors, a 720 MW station built on property owned by the Idaho National Laboratory to provide power to ratepayers in Utah, was scrapped in November 2023 amid rising costs.

2024 marked a breakout year for nuclear power in the U.S., as Congress passed new legislation to streamline reactor regulations, Microsoft put up $16 billion to reopen the mothballed unit at Pennsylvania’s Three Mile Island, and SMR developers lined up major deals with Amazon and Google.

Yet no SMR developer got the green light from the NRC to become the nation’s second certified design.

“Most of our competitors are essentially offering the technology but don’t want to take any risk,” Springman said.

In other words, those developers will design and license the technology and make money off the intellectual property, he said, but utilities and construction firms must provide the financing, time, and materials.

“You have this stagnation where no one wants to stand behind the project,” Springman said. “Enter Holtec. We can manufacture the parts, build the plant, and arrange the financing for the project. We can also manage the spent fuel … and we can decommission the plant at end of life. We can do the entire spectrum of the project. There’s no U.S. company that can offer all of that.”

Holtec is betting its decades of manufacturing know-how, experience managing complex nuclear projects, and early engagement with federal regulators will secure approval fast enough to construct both its SMRs in the next five years — a breakneck speed by the standards of reactor construction.

The only two new reactors built from scratch in the U.S. in decades were completed at the Alvin W. Vogtle Electric Generating Plant in northern Georgia last spring. The pair of 1,100 MW Westinghouse AP1000s followed the NRC’s part 52 combined licensing pathway, which granted approval to build and operate the reactors. While the approach was meant to get the units online faster than the traditional licensing process, the design tweaks that needed to be made during the first-of-a-kind build required repeatedly going back to the NRC for approvals that delayed the project and helped drive it billions of dollars over budget.

Instead, Holtec said it would follow the traditional part 50 process, which requires the company to obtain the construction and operating licenses separately.

“We prefer part 50 because we believe on a first-of-a-kind project, there’s less regulatory risk and more flexibility in that process to allow for learnings during construction,” Springman said.

Holtec started talks with the NRC five years ago and “over the last three years really stepped up engagement” by submitting white papers and topical reports, he said.

The company said it plans to submit the first part of its construction permit application in the first quarter of 2026 and the second part in the second quarter of 2027, then apply for an operating license in the first three months of 2029.

Thanks to conversations already underway, Springman said, Holtec will have incorporated the NRC’s feedback into its application by the time it submits paperwork. “They know it’s coming, and we have reduced risk from a regulatory perspective,” he said.

Already, Holtec updated the design of its SMR, nearly doubling the output of the proposed machine from 160 MW to the 300 MW model the company is now planning to build. Research by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology suggests the cheapest reactor to build in the U.S. next, however, would be another AP1000, since the design is settled and the size allows power-plant owners to benefit from economies of scale.

“I love the idea of restoring nuclear operation to sites that have lost it, and I love even more building new reactors where we had fewer,” said Mark Nelson, a nuclear engineer and founder of the consultancy Radiant Energy Group. “It’ll be interesting to see whether the right size of reactor is smaller or larger in the future.”

Despite some pushback from antinuclear groups, the project is gaining local political backing. In December, the board of commissioners in Michigan’s Van Buren County voted to support construction of the SMRs.

“I’m thrilled — it’d be historic,” said Shawn Connors, 69, a retired technical publisher who grew up in Kalamazoo, owns a condo in South Haven, about five miles north of the Palisades plant, and now volunteers as an advocate for nuclear power. “Palisades might become the focus of the world because this is where you can have the old [pressurized water reactor] operating and two new SMRs operating right next to it. You’ve got the old and the new right there together.”

This is the first article in our four-part series “Boon or bane: What will data centers do to the grid?”

In January, Virginia lawmakers unveiled a raft of legislation aimed at putting some guardrails on a data center industry whose insatiable hunger for electricity threatens to overwhelm the grid.

As the home of the world’s densest data center hub, Virginia is on the vanguard of dealing with these challenges. But the state is far from alone in a country where data center investments may exceed $1 trillion by mid-2029, driven in large part by “hyperscalers” with aggressive AI goals, like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft.

“If we fail to act, the unchecked growth of the data center industry will leave Virginia’s families, will leave their businesses, footing the bill for infrastructure costs, enduring environmental degradation, and facing escalating energy rates,” state Sen. Russet Perry, a Democrat representing Loudoun County, the heart of Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” told reporters at the state capitol in Richmond last month. “The status quo is not sustainable.”

Perry’s position is backed by data. A December report commissioned by Virginia’s legislature found that a buildout of data centers to meet “unconstrained demand” would double the state’s electricity consumption by 2033 and nearly triple it by 2040.

To meet the report’s unconstrained scenario, Virginia would need to erect twice as many solar farms per year by 2040 as it did in 2024, build more wind farms than all the state’s current offshore wind plans combined, and install three times more battery storage than Dominion Energy, the state’s biggest utility, now intends to build.

Even then, Virginia would need to double current power imports from other states. And it would still need to build new fossil-gas power plants, which would undermine a state clean energy mandate. Meeting just half the unconstrained demand would require building seven new 1.5-gigawatt gas plants by 2040. That’s nearly twice the 5.9 gigawatts’ worth of gas plants Dominion now plans to build by 2039, a proposal that is already under attack by environmental and consumer groups.

But Perry and her colleagues face an uphill battle in their bid to more closely regulate data center growth. Data centers are big business in Virginia. Gov. Glenn Youngkin, a Republican, has called for the state to “continue to be the data center capital of the world,” citing the up to 74,000 jobs, $9.1 billion in GDP, and billions more in local revenue the industry brings. Most of the proposed data center bills, which include mandates to study how new data centers could impose additional costs on other utility customers and worsen grid reliability, have failed to move forward in the state legislature as of mid-February.

Still, policymakers can’t avoid their responsibility to “make sure that residential customers aren’t necessarily bearing the burden” of data center growth, Michael Webert, a Republican in Virginia’s House of Delegates who’s sponsoring one of the data center bills, said during last month’s press conference.

From the mid-Atlantic down to Texas, tech giants and data center developers are demanding more power as soon as possible. If utilities, regulators, and policymakers move too rashly in response, they could unleash a surge in fossil-gas power-plant construction that will drive up consumer energy costs — and set back progress on shifting to carbon-free energy.

But this outcome is not inevitable. With some foresight, the data center boom can actually help — rather than hurt — the nation’s already stressed-out grid. Data center developers can make choices right now that will lower grid costs and power-system emissions.

And it just so happens that these solutions could also afford developers an advantage, allowing them to pay less for interconnection and power, win social license for their AI products, and possibly plug their data centers into the grid faster than their competitors can.

When it comes to the grid, the nation faces a computational crossroads: Down one road lie greater costs, slower interconnection, and higher emissions. Down the other lies cheaper, cleaner, faster power that could benefit everyone.

After decades with virtually no increase in U.S. electricity demand, data centers are driving tens of gigawatts of power demand growth in some parts of the country, according to a December analysis from the consultancy Grid Strategies.

Providing that much power would require “billions of dollars of capital and billions of dollars of consumer costs,” said Abe Silverman, an attorney, energy consultant, and research scholar at Johns Hopkins University who has held senior policy positions at state and federal energy regulators and was an executive at the utility NRG Energy.

Utilities, regulators, and everyday customers have good reason to ask if the costs are worth it — because that’s far from clear right now, he said.

A fair amount of this growth is coming from data centers meant to serve well-established and solidly growing commercial demands, such as data storage, cloud computing, e-commerce, streaming video, and other internet services.

But the past two years have seen an explosion of power demand from sectors with far less certain futures.

A significant, if opaque, portion is coming from cryptocurrency mining operations, notoriously unstable and fickle businesses that can quickly pick up and move to new locations in search of cheaper power. The most startling increases, however, are for AI, a technology that may hold immense promise but that doesn’t yet have a proven sustainable business model, raising questions about the durability of the industry’s power needs.

Hundreds of billions of dollars in near-term AI investments are in the works from Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft as well as private equity and infrastructure investors. Some of their announcements strain the limits of belief. Late last month, the CEOs of OpenAI, Oracle, and SoftBank joined President Donald Trump to unveil plans to invest $500 billion in AI data centers over the next four years — half of what the private equity firm Blackstone estimates will be invested in U.S. AI in total by 2030.

Beyond financial viability, these plans face physical limits. At least under current rules, power plants and grid infrastructure simply can’t be built fast enough to provide what data center developers say they need.

Bold data center ambitions have already collided with reality in Virginia.

“It used to take three to four years to get power to build a new data center in Loudoun County,” in Virginia’s Data Center Alley, said Chris Gladwin, CEO of data analytics software company Ocient, which works on more efficient computing for data centers. Today it “takes six to seven years — and growing.”

Similar constraints are emerging in other data center hot spots.

The utility Arizona Public Service forecasts that data centers will account for half of new power demand through 2038. In Texas, data centers will make up roughly half the forecasted new customers that are set to cause summer peak demand to nearly double by 2030. Georgia Power, that state’s biggest utility, has since 2023 tripled its load forecast over the coming decade, with nearly all of that load growth set to come from the projected demands of large power customers including data centers.

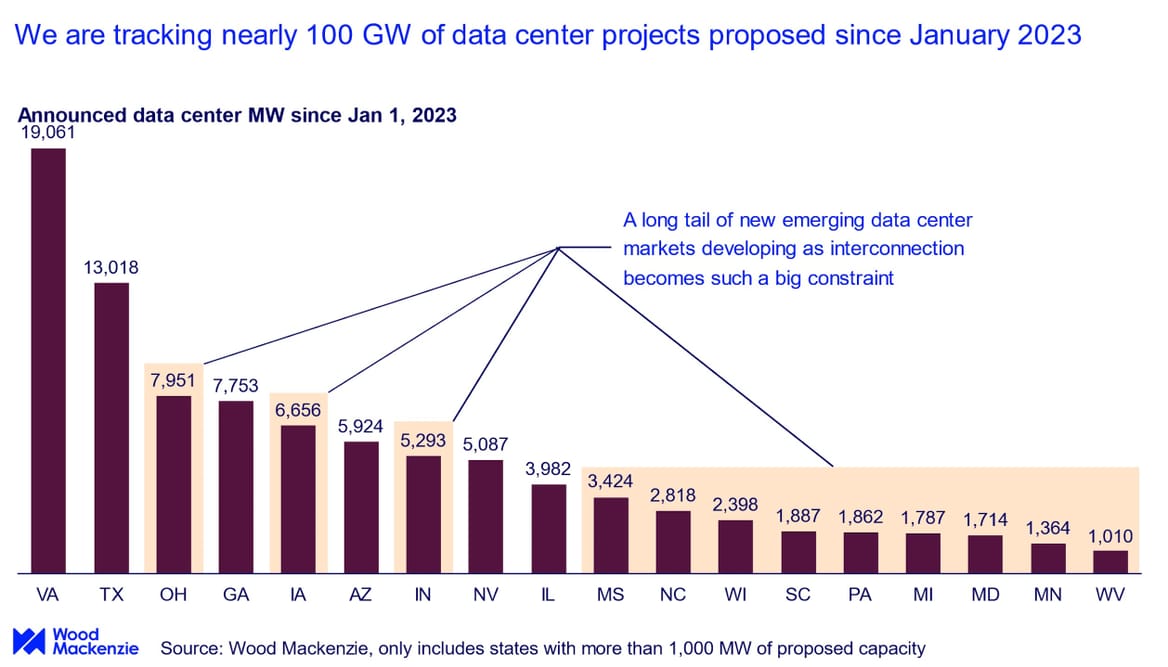

These saturated conditions are pushing developers into new markets, as the below chart from the energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie shows.

“There’s more demand at once seeking to connect to the system than can be supplied,” Chris Seiple, vice chairman of Wood Mackenzie’s power and renewables group, said in a December interview.

Of that demand growth, only a fraction can be met by building new solar and wind farms, Seiple added. And “unfortunately, those additions aren’t necessarily happening where a lot of the demand growth is happening, and they don’t happen in the right hours,” he said.

Seiple is referring to data centers’ need for reliable round-the-clock power, and utilities’ responsibility to provide it, including at moments of peak demand, usually during hot summers and cold winters. A lot of the money utilities spend goes toward building the power plants and grid infrastructure needed to meet those demand peaks.

Where renewables fall short, other resources like carbon-free hydropower, nuclear, geothermal, or clean-powered batteries could technically be built to serve at least a large portion of data center demand. But that’s generally not what’s playing out on the ground.

Instead, the data center boom is shaping up to be a huge boon for fossil-gas power plants. Investment bank Goldman Sachs predicts that powering AI will require $50 billion in new power-generation investment by 2030: 40% of it from renewables and 60% from fossil gas.

Even tech firms with clean energy goals, like Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft, are having trouble squaring their soaring power needs with their professed climate commitments.

Over the past decade, those four companies have secured roughly 40 GW of U.S. clean power capacity, according to research firm BNEF. But in the past four years, their growing use of grid power, which is often generated using plenty of fossil gas, has pushed emissions in the wrong direction. Google has seen a 48% increase since 2019, and Microsoft a 29% jump since 2020.

The inability to match growing demand with more clean power isn’t entirely these hyperscalers’ fault. Yearslong wait times have prevented hundreds of gigawatts of solar and wind farms and batteries from connecting to congested U.S. power grids.

Tech firms are also pursuing “clean firm” sources of power. Amazon, Google, Meta, and Microsoft have pledged to develop (or restart) nuclear power plants, and Google has worked with advanced-geothermal-power startup Fervo Energy. But these options can’t be brought online or scaled up quickly enough to meet short-term power needs.

“The data center buildout, especially now with AI, is creating somewhat of a chaotic situation,” said James West, head of sustainable technologies and clean-energy research at investment banking advisory firm Evercore ISI. Hyperscalers are “foregoing some of their sustainability targets a bit, at least near-term.”

And many data center customers and developers are indifferent to clean energy; they simply seek whatever resource can get their facility online first, whether to churn out cryptocurrency or win an advantage in the AI race.

Utilities that have sought for years to win regulatory approval for new gas plants have seized on data center load forecasts as a new rationale.

A recent analysis from Frontier Group, the research arm of the nonprofit Public Interest Network, tallied at least 10.8 GW of new gas-fired power plants being planned by utilities, and at least 9.1 GW of fossil-fuel power plants whose closures have been or are at risk of being delayed, to meet projected demand.

In Nebraska, the Omaha Public Power District has delayed plans to close a 1950s-era coal plant after Google and Meta opened data centers in its territory. Last year, Ohio-based utility FirstEnergy abandoned a pledge to end coal use by 2030 after grid operator PJM chose it to build a transmission line that would carry power from two of its West Virginia coal plants to supply northern Virginia.

“This surge in data centers, and the projected increases over the next 10 years in the electricity demand for them, is really already contributing to a slowdown in the transition to clean energy,” said Quentin Good, policy analyst with Frontier Group.

In some cases, tech companies oppose these fossil-fuel expansion plans.

Georgia Power last month asked regulators to allow it to delay retirement of three coal-fired plants and build new gas-fired power plants to meet a forecasted 8 GW of new demand through 2030. A trade group representing tech giants, which is also negotiating with the utility to allow data centers to secure more of their own clean power, was among those that criticized the move for failing to consider cleaner options.

But in other instances, data center developers are direct participants.

In Louisiana, for example, Meta has paired a $10 billion AI data center with utility Entergy’s plan to spend $3.2 billion on 1.5 GW’s worth of new fossil-gas power plants.

State officials have praised the project’s economic benefits, and Meta has pledged to secure clean power to match its 2 GW of power consumption and to work with Entergy to develop 1.5 GW of solar power. But environmental and consumer advocates fear the 15-year power agreement between Meta and Entergy has too many loopholes and could leave customers bearing future costs, both economic and environmental.

“In 15 years, Meta could just walk away, and there would be three new gas plants that everyone else in the state would have to pay for,” said Logan Atkinson Burke, executive director of the nonprofit Alliance for Affordable Energy. The group is demanding more state scrutiny of the deal and has joined other watchdog groups in challenging Entergy’s plan to avoid a state-mandated competitive bidding process to build the gas plants.

In other cases, AI data center developers appear to be making little effort to coordinate with utilities. In Memphis, Tennessee, a data center being built by xAI, the AI company launched by Elon Musk, was kept secret from city council members and community groups until its June 2024 unveiling.

In the absence of adequate grid service from Memphis’ municipal utility, the site has been burning gas in mobile generators exempt from local air-quality regulations, despite concerns from residents of lower-income communities already burdened by industrial air pollution.

In December, xAI announced a tenfold increase in the site’s computing capacity — a move that the nonprofit Southern Alliance for Clean Energy estimates will increase its power demand from 150 MW to 1 GW, or roughly a third of the entire city’s peak demand.

The nonprofit had hoped that “Musk would use his engineering expertise to bring Tesla megapacks [batteries] with solar and storage capability to make this facility a model of clean, renewable energy,” its executive director, Stephen Smith, wrote in a blog post. But now, the project seems more like “a classic bait and switch.”

If gas plants are built as planned to power data centers, dreams of decarbonizing the grid in the near future are essentially out the window.

But data centers don’t need to be powered by fossil fuels; it’s not a foregone conclusion.

As Frontier Group’s Good noted during last month’s Public Interest Network webinar, “The outcome depends on policy, and the increase in demand is by no means inevitable.”

It’s up to regulators to sort this out, said Silverman of Johns Hopkins University. “There are all these tradeoffs with data centers. If we’re asking society to make tradeoffs, I think society has a right to demand something from data centers.”

That’s what the Virginia lawmakers proposing new data center bills said they were trying to do. Two of the bills would order state regulators to study whether other customers are bearing the costs of data center demand — a risk highlighted by the legislature’s December report, which found unconstrained growth could increase average monthly utility bills by 25% by 2040. Those bills are likely to be taken up in conference committee next month.

Other bills would give local governments power to review noise, water, and land-use impacts of data centers seeking to be sited in the state, require that data centers improve energy efficiency, and mandate quarterly reports of water and energy consumption.

Another sought to require that proposed new data centers undergo review by state utility regulators to ensure they won’t pose grid reliability problems. Democratic Delegate Josh Thomas, the bill’s sponsor, said that’s needed to manage the risks of unexamined load growth. Without that kind of check, “we could have rolling blackouts. We could have natural gas plants coming online every 18 months,” he said.

But that bill was rejected in a committee hearing last month, after opponents, including representatives of rural counties eager for economic development, warned it could alienate an industry that’s bringing billions of dollars per year to the state’s economy.

Data center developers have the ability to minimize or even help drive down power system costs and carbon emissions. They can work with utilities and regulators to bring more clean energy and batteries onto the grid or at data centers themselves. They can manage their demand to reduce grid strains and lower the costs of the infrastructure needed to serve them. And in so doing, they could secure scarce grid capacity in places where utilities are otherwise struggling to serve them.

The question is, will they? Silverman emphasized that utilities and regulators must treat grid reliability as their No. 1 priority. “But when we get down to the next level, are we going to prioritize affordability, which is very important for low-income customers? Are we going to prioritize meeting clean energy goals? Or are we going to prioritize maximizing data center expansion?” he asked.

Given the pressure to support an industry that’s seen as essential to U.S. economic growth and international competitiveness, Silverman worries that those priorities aren’t being properly balanced today. “We’re moving forward making investments assuming we know the answer — and it’s not like if we’re wrong, we’re getting that money back.”

In part 2 of this series, Canary Media reports on a key problem with data center plans: It’s near impossible to know how much they’ll impact the grid.

When solar developers look to build big projects on farmland, the same arguments tend to come up: The array will waste useful agricultural tracts, ruin views, and sully the pastoral character of the rural community, public commenters say.

In Ohio, a state where these debates have long played out, comments like that have even led the state’s power siting board to block projects. These sentiments, in Ohio and beyond, are sometimes motivated by misinformation from anti-solar groups, including organizations with fossil fuel industry ties.

But as one solar developer recently found, hundreds of negative comments don’t necessarily mean hundreds of people oppose a project, Kathiann Kowalski reported this week for Canary Media.

The Ohio Power Siting Board received more than 2,500 comments about the Grange Solar Grazing Center, which aims to bring solar and sheep together on a 2,570-acre plot in the state’s Logan County. When the project’s developer took a closer look at the feedback, it found 16 individuals had collectively submitted more than 140 of those comments, most of them opposing the project. When accounting for repeats, the company found that 80% of individual commenters actually back the solar array.

Supportive commenters said they expect the Grange project to bring jobs and public funding to the county. A 2023 report from the Purdue Center for Regional Development verified that solar projects typically create short-term construction jobs, bring in tax revenue, and help raise farmers’ land values.

Taking a step back, it’s worth noting that more than three-quarters of Americans support expanding solar, per a May 2024 survey from Pew Research Center. That includes 64% of Republicans — though the group has soured on the energy source in recent years.

Mass layoffs hit the Energy Department

The Trump administration closed last week with a big — but not totally unexpected — blow to the U.S. Energy Department workforce. As many as 2,000 probationary DOE employees were laid off, ending what one staffer described to Latitude Media as a “weird, quiet limbo” following President Donald Trump’s inauguration.

But the layoff didn’t last long for a group of employees at the Bonneville Power Administration. About 30 workers who maintain power lines and other infrastructure at the Pacific Northwest grid operator were asked back just days later, a union leader told Politico.

Clean energy smashed a record last year

The U.S. added a whopping 48.2 GW of new utility-scale solar, wind, and battery storage capacity in 2024, an increase of 47% from the year before, according to new research by energy data firm Cleanview. Texas led the way on solar and wind and was the runner-up on battery installations after California. Still, fossil fuels remain responsible for more than half of the country’s electricity generation — and the Trump presidency is likely to slow clean energy development this year. Akielly Hu breaks down the whole report for Canary Media here.

Green bank clawback: The new head of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency wants to claw back $20 billion in federal green bank funding that was meant to help low-income communities build solar arrays, deploy electric school buses, and otherwise implement clean energy. (Canary Media)

Electric truck breakdown: Electric and fuel-cell truck startup Nikola, once valued more than Ford at $30 billion, files for bankruptcy protection after failing to raise money or find a buyer. (CNBC)

Rural clean energy freeze: Farmers across the country are taking a hit from the federal funding freeze as money stops flowing to a program supporting clean energy installations and energy-efficiency upgrades for agricultural and rural businesses. (Associated Press)

Sustainable jet fuel resumes takeoff: The Trump administration finalized a $1.44 billion loan for a sustainable aviation fuel refinery in Montana, a first since it paused all deals made by the Energy Department’s Loan Programs Office under Biden. (Canary Media)

Derailing environmental justice: Advocates call out the Trump administration for shutting down the federal government’s environmental justice departments, saying the decision will“create challenges and impacts that will last well beyond the current administration.” (Inside Climate News)

Cutting carbon in construction: As the federal government drops its commitment to buying lower-carbon building materials, several states are forming coalitions and ramping up their efforts. (Canary Media)

Offshore wind blowback: President Trump’s executive order halting offshore wind permitting could make it difficult or impossible for several Northeastern states to reach their ambitious climate goals. (Washington Post)

Dive deeper: A conservative group that once opposed Dominion Energy’s major Virginia offshore wind farm is now encouraging the project to go ahead, saying that halting it could put ratepayers on the hook for $6 billion already spent. (Canary Media)

Can tariffs clean up steel? A U.S. steel industry advocate cheers Trump’s 25% tariff on imports, saying those imposed during the last Trump administration spurred $20 billion in investment to modernize, decarbonize, and electrify the industry. (E&E News)

Cutting fossil fuels out of transportation and buildings will mean embracing electric vehicles and equipping homes and offices with heat pumps. But cleaning up these sectors will take much more than tackling their energy supply — it’ll also require eliminating carbon emissions that come from producing the materials that roads and buildings are made of.

A growing number of states are starting to do just that, with policies that take a more holistic view of the climate challenge.

Nine states have enacted Buy Clean laws to boost demand for lower-carbon steel, concrete, asphalt, glass, and other industrial products. California enacted the nation’s first such policy in 2017, followed in subsequent years by Oregon, Colorado, Washington, New York, New Jersey, Maryland, Minnesota, and Massachusetts. Agencies in other states are starting to adopt similar strategies, including by collecting emissions data about products used in public works projects.

“We’ve [historically] invested a lot in policies to improve the energy efficiency of buildings,” said Hanna Waterstrat, director of the Washington State Department of Commerce’s state efficiency and environmental performance office. “But the footprint of the materials — from the manufacture, transport, installation, maintenance, and disposal — can actually be the equivalent of, or bigger than, the entire greenhouse-gas footprint of operating a building through its lifetime.”

The so-called embodied carbon in construction projects represents a significant share of the world’s annual emissions, with an estimated 11% coming from materials used in buildings alone. That’s largely because manufacturers consume huge amounts of fossil fuels to make products like steel and cement. State authorities and companies have tended to overlook these emissions when assessing the climate impact of, say, a new office tower or highway.

“That’s been a gap in the land of climate and energy policy so far,” said Waterstrat, who leads her department’s efforts to implement Washington’s Buy Clean and Buy Fair strategy.

Until last month, the states working to shrink that policy gap had a powerful partner in the federal government.

The Biden administration launched the Federal-State Buy Clean Partnership in 2023 to build upon existing efforts and accelerate the U.S. market for cleaner construction materials. Federal agencies designated billions of dollars in climate funding to help state governments and contractors track emissions and to enable domestic manufacturers to decarbonize their operations.

President Donald Trump has since abandoned the federal Buy Clean strategy and is attempting to rescind related grant programs. The about-face will undoubtedly delay a deep transformation of the country’s construction sector. But state agencies and industry associations say they’re forging ahead — guided by their own laws and commitments to slash embodied carbon.

“Buy Clean is a great example of how states and other nonfederal actors can continue to press forward on climate action, regardless of what the federal government does,” said Casey Katims, executive director of the U.S. Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition of two dozen governors.

The group is working to maintain collaboration among the 13 states that joined the federal-state Buy Clean initiative, and in recent weeks it has downloaded the datasets, analytical tools, and other relevant resources that the Trump administration could wipe from the internet. Katims noted that the alliance formed under similar circumstances in 2017, after Trump withdrew the U.S. from the Paris climate agreement for the first time.

“It’s quite literally in our DNA to sustain climate work at the state level,” he said.

The broader Buy Clean vision is to harness the government’s massive purchasing power to jump-start the private market for low-carbon industrial materials. Companies bidding to construct new public buildings or bridges must show they can not only compete on cost but also on the carbon intensity of their concrete or steel, which in turn creates demand for more cleanly produced products.

Today, states are largely still laying the foundation for this future reality.

The first place many agencies start is by requiring suppliers to furnish environmental product declarations. EPDs, which are often likened to climate nutrition labels, provide granular data about the emissions associated with extracting, manufacturing, and transporting individual materials. Defining criteria for individual products involves lengthy discussions between state authorities and industry groups. The EPDs themselves can cost companies thousands of dollars and dozens of hours to complete.

In 2021, the Washington State Legislature commissioned a pilot study to collect data about both the environmental impacts and labor standards related to materials used in five state construction projects. Three years later, the state adopted its Buy Clean and Buy Fair law, which requires state agencies and public universities to report on the impacts of concrete, wood, and steel products purchased for new state-owned building projects.

Waterstrat said her team has since developed specifications and language for companies to follow to ease the process of bidding on projects. Her office is also working on a database for EPDs to show the carbon intensity of the materials the state procures and to inform future policymaking. Eventually, the idea is to set limits around products’ carbon footprints — but for now, the state’s law doesn’t call for that.

“Just having that knowledge and data is really the first step in understanding what your procurement choices are,” Waterstrat said, adding that she’s “hopeful it will lead project owners to select lower-carbon materials.”

A handful of states that are gathering EPDs also require construction products to meet certain emissions thresholds, which are known as global warming potential limits.

In 2022, California’s Buy Clean policy began requiring that four categories — structural steel, concrete reinforcing steel, flat glass, and insulation — used in public works projects meet GWP limits equal to or below the industry average. The Buy Clean Colorado Act similarly calls for setting industry-average thresholds for three types of steel, as well as asphalt, concrete, glass, and wood used in new state projects from January 2024 on. Next year, Colorado’s Office of the State Architect will review those limits and report to the Legislature on the program’s progress.

New York, for its part, set GWP standards in 2023 for concrete mixes used in all state building and transportation projects, making it the first state to do so. The Buy Clean Concrete guidelines, which began as voluntary, became mandatory last month. The current threshold is equivalent to 150% of the emissions for average concrete mixes in the eastern U.S. The idea is to create a policy that’s initially attainable not just for major manufacturers but also “mom-and-pop concrete plants” in rural parts of the state “for whom this is all fairly new,” said Mariane Jang, a senior policy advisor on the resiliency and sustainability team in New York state’s Office of General Services.

However, starting in 2027, the limits will progressively lower to reflect ongoing efforts to slash emissions from cement and concrete production. In the meantime, “the aim is to do more capacity-building and to engage even those smaller companies to prepare them for the upcoming changes,” Jang said.

The ability to gather accurate data from many disparate suppliers is essential to achieving the ultimate goal of Buy Clean: slashing embodied carbon from construction materials.

That work will potentially get harder if the Trump administration succeeds in its attempts to claw back congressionally mandated climate and energy spending.

Among the funding stuck in political purgatory is a nearly $160 million grant program by the Environmental Protection Agency to help dozens of businesses develop “high-quality” EPDs for 14 material categories.

The National Asphalt Pavement Association was selected last year to receive $10 million of that funding, which hasn’t yet made it out the door, according to Richard Willis, who manages the organization’s team that works on engineering and sustainability issues. The industry association has developed widely used software that helps asphalt-mix producers develop and publish EPDs for individual plants and mixtures. But using the tool costs companies around $3,000 to $6,000 per plant.

Willis said the EPA funding would be used to reduce costs and other barriers for asphalt-mix producers while helping fill in the “data gaps” from the businesses that supply additives. The contents of asphalt pavement — made from aggregate and a liquid petroleum-based binder — can vary widely depending on the local climate and the types of ingredients available nearby.

“Asphalt is about as local of a material as it gets,” Willis said. That makes it tricky to create robust EPDs using general industry information or to develop plans for curbing emissions at a given plant.

A $1.2 billion program from the Federal Highway Administration is similarly ensnared in Trump’s funding freeze. In November, the FHWA selected transportation agencies in 37 states; Washington, D.C.; and Puerto Rico to receive grants to help them study, track, and ultimately purchase cleaner materials for roads and highways.

New York was tapped to receive $31.9 million, though because the funding wasn’t legally obligated before Trump took office, it’s unclear if the state will ever actually get it, said Bruce Barkevich, who is vice president of the New York Construction Materials Association, a trade group representing producers of asphalt, aggregate, and ready-mix concrete in the state.

The timing of the grant would’ve been especially helpful for New York manufacturers and suppliers working to develop EPDs. State construction projects that use over 8,000 short tons of asphalt are now required to gather such data; projects of all sizes will have to do the same starting in 2026. New York’s policy, Executive Order 22, also requires agencies to report the quantities of concrete mixes, five types of steel products, and three types of glass products procured for state projects and provide EPDs when available.

“Even with that [funding uncertainty], we’re not losing the emphasis on sustainable pavements and low-carbon materials, because we’re in New York state — we have laws on the books,” Barkevich said. He added that companies and agencies in the state have worked together for years to curb emissions from asphalt production, including by reducing temperatures used in asphalt-mixing plants and incorporating more recycled material.

Emily Rubenstein, the deputy commissioner for resiliency and sustainability in New York state’s Office of General Services, said her team continues to press ahead with the state’s Buy Clean strategy, including by hosting public webinars, meeting with industry, and training staff in various state agencies. The office is also currently analyzing embodied-carbon data from state projects with the goal of identifying future pathways for reducing embodied carbon.

“This work takes a village, and we’ve been thrilled with how both supporting agencies and industries have been in [backing] the transition,” she said, adding that she’s also glad the U.S. Climate Alliance has picked up the mantle of organizing states.

In New York and other Buy Clean states, program leaders said they’re still meeting quarterly through the climate alliance and trading notes to learn from each other’s experiences. Such collaboration is especially pertinent now that the biggest player in the game — the federal government — is stepping back, said Ted Fertik, vice president for manufacturing and industrial policy at the BlueGreen Alliance, a coalition of labor unions and environmental groups.

“There’s a broad recognition that, in most cases, one state’s procurement is probably not sufficient to drive large-scale shifts in production processes,” Fertik said. “So there will need to be more intentional efforts around harmonizing [state efforts] to drive decarbonization.”

Connecticut could become the latest state to pursue networked geothermal systems as a way of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, improving public health, and reducing energy cost burdens for residents.

State lawmakers are considering a bill, HB 6929, that would create a grant and loan program to support development of geothermal networks, which tap into energy stored in the earth to deliver heating and cooling to multiple buildings in one neighborhood.

“Thermal energy networks are an incredibly exciting technological breakthrough,” said Samantha Dynowski, state director of the Sierra Club’s Connecticut chapter, testifying in favor of the bill during a Tuesday hearing before the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Energy and Technology.

The bill enjoys wide support from environmental advocates, community leaders, and business interests. Several parties are pushing for changes they say would make even more of an impact, such as requiring utilities to propose pilot projects, following the example of New York, which included such a mandate in a 2022 law.

Also, as drafted, the bill does not specify a funding mechanism for the grant and loan program it would create. Several stakeholders have suggested adding language that authorizes the state to issue a bond to fund the program.

“It’s a one-time capital investment that would yield long-term environmental and economic benefits,” said Connor Yakaitis, deputy director of the Connecticut League of Conservation Voters, who also suggested a budget of $20 million for the program.

Advocates point to the emissions reductions the systems can achieve. More than 40% of the state’s households burn heating oil to stay warm, and another 37% use natural gas; meanwhile, the only emissions associated with geothermal heat come from generating the electricity used to run the heat pumps installed in buildings across the system.

Geothermal networks can also save customers money because the energy underground is free and ground-source heat pumps use far less electricity than air-source heat pumps or electric resistance heat. In Framingham, Massachusetts, the country’s first utility-scale geothermal network is projected to cut some customers’ heating bills by as much as 75% this winter, testified Eric Bosworth, clean technologies manager for Eversource, which built and owns the project.

The adoption of geothermal networks can also help utilities — and their workers — transfer skills into a new field as energy systems transition away from natural gas, supporters said.

“They have experience and expertise that can be leveraged,” Bosworth said, noting that gas industry workers constructed much of the Framingham system.

Geothermal heat pumps have been around for more than 100 years, but the idea of using the equipment to serve dozens of homes connected in a loop first started to catch on in 2017, when Massachusetts energy transition nonprofit HEET began pitching it to utilities. They were interested, and in June 2024, Eversource brought the Framingham system online. Today the network serves 135 residential and commercial customers in the city of Framingham. National Grid is also in the process of developing a system in Boston.

Other states have seen the promise in geothermal networks, too. Six states in addition to New York and Massachusetts have passed legislation supporting utility construction of thermal energy networks, according to the Building Decarbonization Coalition, and some 22 to 27 pilot projects have been proposed to regulators nationwide.

In Connecticut, environmental groups have been discussing the geothermal possibilities with utilities for a few years, said Shannon Laun, the Conservation Law Foundation’s vice president for Connecticut. Eversource has shown interest in developing a pilot project and taken preliminary steps to seek approval to proceed, but specific legislation supporting geothermal networks would be more likely to galvanize action from utilities, she said.

“We’re starting to see some new momentum with this bill,” Laun said.

Canary Media’s Electrified Life column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

Kathy Palmer was intrigued when her neighbor, an environmental lawyer she’d met while volunteering on a Minneapolis climate committee, sang the praises of the new heat pump he had installed in his home.

Now, Palmer is enjoying the warmth of her own heat pump.

For the past three decades, the 72-year-old retired educator has relied on a fossil-gas boiler system to heat her two-story stucco home in Minneapolis — first via cast-iron radiators and then through radiant flooring as well.

That system was sluggish, said the resident of the coldest major city in the continental U.S., where the temperature falls below 0 degrees Fahrenheit more than 20 days out of the year. Palmer often needed to wait an hour or more for the boiler to warm up her home.

She couldn’t afford to replace her entire gas system, but she realized a heat pump could supplement it. Her new heat pump — a 3-ton Daikin model that delivers heat at nearly its maximum output down to 5˚F and works at a reduced capacity at -13ˆF and lower — has been a revelation. The two wall-mounted air handling units rev up in one minute to bathe a space with warm air. Give them 10 to 15 minutes, and they make a chilly room comfortable, she said. “It’s wonderful to have that happen so quickly.”

Palmer is just one of the tens of thousands of U.S. residents who have installed heat pumps in recent years. The technology is crucial for kicking fossil fuels out of homes and has proved again and again that it works even in bitingly cold climates. Maine has rebated more than 175,000 heat pumps for space heating since 2014. And Vermont installed more than 10,700 heat pumps through its rebate program last year alone. (Minnesota utilities will make heat-pump rebate data publicly available starting in April 2025, a spokesperson of the community-based nonprofit Center for Energy and Environment told me.)