A new analysis shows that a clear majority of people submitting comments on a planned central Ohio solar farm support the project — a stark contrast with how opponents have portrayed public sentiment.

Open Road Renewables, the developer seeking a permit to build the Grange Solar Grazing Center in Logan County, reviewed more than 2,500 comments submitted to the Ohio Power Siting Board through Feb. 11 regarding its permitting case. After accounting for repeat commenters who submitted multiple times, the company found 80% of commenters expressed support for its project.

A project’s popularity is a potential factor in site permit decisions, but how regulators use that information is the subject of a pending case before the Ohio Supreme Court. Until the question of how state regulators should measure “public interest” is resolved, solar advocates and developers say it’s critical to closely examine public comments before drawing conclusions.

“Anyone can file 10 different comments, but if you’re using that to determine public opinion, just based on nominally how many comments there are, that’s kind of missing the mark,” said Doug Herling, vice president for Open Road Renewables.

Herling took issue with people “gaming” the system, submitting multiple comments to make it appear that the project has more naysayers. The company’s analysis identified more than 600 repeat comments that should not be considered in attempts to quantify support or opposition to the project. As of early February, it found 16 individuals who collectively submitted more than 140 comments, mostly opposing Grange Solar.

Solar opponents, some with ties to fossil fuel groups, have used town halls and other forums to portray utility-scale solar projects as deeply unpopular in rural Ohio. Sustained opposition has led developers to drop plans for at least four large solar developments in Ohio within the past 15 months. Nationally, research released last June by Columbia University’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law documents hundreds of renewable energy projects facing significant opposition across 47 states.

Permitting in Ohio has become especially contentious since passage of a 2021 law that adds hurdles for siting most wind and solar projects over 50 megawatts. Under the law, counties can block new utility-scale projects before they even get to the state siting board. The law doesn’t apply to fossil fuel or nuclear power projects.

The 2021 law exempts Grange Solar and some other projects because they were already in grid operator PJM’s queue when the law took effect. However, Grange Solar isn’t exempt from a provision in the law calling for two local ad hoc board members to join the state siting board’s seven voting members when it deliberates on the project.

Ohio law requires any new generation project to meet eight criteria. They include consideration of impacts on the environment, water conservation, and agricultural land. Other factors include whether a facility “will serve the interests of electric system economy and reliability” and “the public interest, convenience, and necessity.”

Ohio statutes don’t spell out what “public interest” means, and the power siting board declined environmental advocates’ requests to define the term when other rule revisions took effect last year.

Yet the board has denied multiple permit applications for solar projects based entirely or primarily on a large percentage of public comments or local governments opposing them. The developer in one such case, Vesper Energy, challenged the siting board’s popularity-contest approach in denying its Kingwood Solar project. The case is now before the Ohio Supreme Court, with oral arguments set for March 13.

That backdrop prompted Open Road Renewables to take a closer look at the comments in the Grange Solar case.

“Given that the siting board puts a weight on local public opinion and any resolutions made by local public bodies, we just felt it deserved that scrutiny,” Herling said.

The company submitted an initial analysis of public comments through Feb. 4 and found three-quarters of 806 unique commenters in the docket favored the project, compared with one-fourth in opposition. Among the commenters within Logan County, supporters still outnumbered opponents by about two to one.

A flurry of filings more than doubled the total number of comments, and the developer prepared an updated analysis through Feb. 11. Among nearly 2,000 commenters, supporters outnumbered opponents four to one. Opinion was more divided within Logan County, but allies still exceeded critics, Open Road Renewables’ most recent analysis said.

Supporters’ reasons for backing the project include jobs and economic benefits. Commenters also approved of the company’s commitment to minimizing impacts on the environment while preserving soil and drainage and screening panels from public view.

“The economic impact is undeniable — jobs for our neighbors and much-needed funding for our schools and public services,” wrote Russells Point resident Sharon Devault in a Jan. 10 comment. “Misinformation about solar energy concerns me. Let’s base decisions on facts, not fear.”

“I support solar energy because of the price of fossil fuels and the problems with them,” said Logan County resident Roger Blank in a Dec. 10 comment.

Some supporting commenters also dismissed project foes’ claims that Grange Solar would hurt tourism in the area. A Jan. 13 comment by Sharon Lenhart said they would continue to visit Logan County and Indian Lake. “The substantial investment in public services will likely make the area a more attractive destination,” Lenhart wrote.

The Ohio Chamber of Commerce also filed a supportive comment on the Grange Solar project, reflecting the business group’s more vocal advocacy for clean energy as a tool for economic development and grid resiliency.

Yet more comments have been submitted in the Grange Solar case, including additional duplicates and comments by opponents who have already weighed in. For example, Logan County resident Shelley Wammes contributed 14 comments in a Feb. 12 packet and another on Feb. 14. Wammes, who did not respond to questions sent via email by Canary Media, also filed 13 comments against the project last August and September.

“I am happy to see that Grange is really trying to take these things into account and recognize that there is support for this project within the community and that it shouldn’t just be outweighed by [a] few loud voices who are shouting a lot of misinformation,” said Shayna Fritz, executive director of the Ohio Conservative Energy Forum. In her view, people’s ability to lease their land for energy projects is a property rights issue.

Nolan Rutschilling, managing director of energy policy for the Ohio Environmental Council, said it’s important that state regulators consider the substance of comments, not just use them as a straw poll for measuring popularity.

Instead of just counting comments, “each perspective and comment must be considered for its substance — especially the truth of any claims — and who the comment represents,” Rutschilling said.

In another solar permitting case last summer, half the unique arguments presented during local public hearings lacked factual support, said Heidi Gorovitz Robertson, a professor at Cleveland State University College of Law who served as an expert witness for the Ohio Environmental Council.

In her view, numbers can provide a sense of the extent of support for particular arguments opposing or supporting a project. But if 1,000 people support a specific point for or against a development, that’s still just one issue for the power siting board’s consideration. An argument based on false information may not deserve weight at all. Other comments are just statements of opinion without evidentiary support, she noted.

“The value of the arguments is as important, or arguably much more important, than the numbers,” Robertson said. “All of this, of course, assumes the agency really wants to know.”

The power siting board’s staff investigation of the Grange Solar project is due by March 3, and the evidentiary hearing is set to start on April 7.

This story was first published by CalMatters.

California’s push to electrify its cars is facing a potentially serious problem: People aren’t buying electric cars fast enough.

After three straight years of strong growth, sales have stabilized in California, raising questions about whether the state will fail to meet its groundbreaking mandate banning sales of gas-powered vehicles.

About a quarter — 25.3% — of all new cars registered in California in 2024 were zero emissions, just slightly more than 25% in 2023, according to new California Energy Commission data. The flat sales follow several years of rapid growth; in 2020, only one in 13 cars sold was zero-emissions. Their share of California’s market is now three times larger than four years ago.

But the slowed pace of growth in the market puts the state’s climate and air pollution goals at risk. Under California’s mandate, approved in 2022, 35% of new 2026 car models sold by automakers must be zero-emissions. That leaves considerable ground to make up as some 2026 models begin rolling out later this year.

The requirement ramps up to 68% for 2030 models, and in 2035, California’s rule bans all sales of gasoline-powered cars.

David Simpson, who owns three car dealerships in Orange County, said he is not seeing increased demand for electric cars. While the initial rollout of some models, such as the GMC Hummer EV, did well at first, the demand did not continue. Sales of the Chevrolet Equinox and Blazer EVs do alright but aren’t strong, either, he said.

“The sales are declining,” Simpson said. “We’ve filled that gap of people who want those cars — and now they have them — and we’re not seeing a big, huge demand. I don’t see households going 100% EV.”

Dave Clegern, a spokesperson for the California Air Resources Board, which oversees the electric car mandates, said in an email that while sales of zero-emission vehicles in California are “less dramatic than in years past,” the flat sales occurred in the context of an overall plateauing of car sales last year.

Although the rules limit what automakers can sell, Californians are not required to buy electric cars. That means if consumer demand doesn’t increase, it could be a major black eye for Gov. Gavin Newsom, who has made electric cars a cornerstone of his agenda to fight climate change and clean the air. A spokesman for Newsom declined to comment.

The state mandate, however, has some flexibility, Clegern said. First of all, it’s a multi-year formula: Each manufacturer’s sales of 2026 zero-emission vehicles must be 35% of its total sales averaged for model years 2022 through 2024.

Manufacturers also can buy credits from automakers that have exceeded the target — companies that only sell electric models, such as Tesla or Rivian. To enforce compliance with California’s sales requirements, state officials could impose steep penalties of $20,000 per vehicle on manufacturers that fall short of quotas.

“Manufacturers may still be in compliance even if they do not achieve these specific sales volumes,” Clegern said.

Brian Maas, president of the California New Car Dealers Association, said automakers could seek to avoid the fines by reducing the number of gas-powered cars they send to California dealers. He said that could leave fewer options for buyers, drive up prices, and push some consumers to Nevada or Arizona to find the car they want, while others will hold on to their older, more polluting vehicles.

“We’re just not going to make the mandate as presently drafted,” so automakers will have to take action, Maas said. “The most rational is to constrain inventory.”

The auto industry group Alliance for Automotive Innovation has been raising these concerns since at least December, when it published a memo entitled “It’s gonna take a miracle: California and states with EV sales requirements.” The group warns the mandate could depress auto sales in California — as well as in other states that adopt its rules.

Last month, John Bozzella, the group’s chief executive, called California’s rules “by any measure not achievable” after President Donald Trump signed an executive order repealing federal rules promoting electric vehicles.

“There’s a saying in the auto business: You can’t get ahead of the customer,” Bozzella said.

The outgoing Biden administration’s U.S. Environmental Protection Agency granted California a waiver in December that allows the state to enforce its requirements phasing out new gas-powered cars. Many experts believe the Trump administration is likely to challenge the waiver through the courts.

Experts also anticipate that Trump could eliminate the $7,500 federal tax credit for zero-emission vehicle purchases, which would increase the cost of buying some electric cars. Newsom vowed last year to continue offering the incentive through state funding, although that promise came before Los Angeles faced devastating wildfires and the state released its fragile budget earlier this year.

Californians have purchased more than 2 million electric cars, leading the nation. The number has doubled in about two years.

But electric vehicle sales, which make up the majority of zero-emission cars, grew by only 1.1% in 2024, with 378,910 sold compared to 374,668 in 2023. Plug-in hybrids, once considered a potential alternative to a purely electric model, remained relatively stable. And sales of hydrogen-powered cars all but collapsed last year, with sales plummeting to a meager 600 in 2024 from 3,119 in 2023.

The slower growth comes amid overall market sluggishness, with all auto sales in California dipping slightly last year to 1,752,030.

Loren McDonald, chief analyst for the charging app Paren, said a major contributor is a shift in consumer demographics.

The state’s market has moved beyond early electric car adopters — affluent, environmentally motivated buyers willing to overlook challenges like limited charging infrastructure and higher costs — and into the mainstream.

He said these new buyers, often from middle-income households or who live in apartment buildings without easy access to charging, are far less forgiving when it comes to electric cars. Concerns about range, broken chargers, and upfront costs are deal-breakers.

Tesla’s market dominance has exacerbated the issue. Many left-leaning California consumers, who were once loyal to Tesla, appear to have distanced themselves because of CEO Elon Musk’s controversial public persona and alliance with Trump.

As Tesla sales have softened, dropping 11% in California last year, the decline has disproportionately affected overall EV registration data in California because of the company’s significant market share, McDonald said.

Affordability remains a crucial hurdle, though McDonald sees signs of improvement. Automakers have ramped up production, leading to competitive pricing and aggressive lease deals — many under $400 per month.

But mainstream consumers are largely unaware that electric vehicles offer long-term savings in fuel and maintenance, McDonald said, adding that better education is needed to convince consumers to take the leap, especially as electric car prices increasingly approach parity with gas-powered vehicles.

McDonald remains optimistic about 2025. The market will benefit from new electric models priced under $50,000 and technological advancements, such as faster charging and vehicle-to-home power capabilities.

One of the nation’s largest hydrogen-powered transit fleets is seeking to switch to a cleaner — and local — fuel source as part of a federally funded clean hydrogen hub.

The Stark Area Regional Transit Authority, or SARTA, provides about 5,000 daily rides to commuters in the Canton, Ohio, area. A decade after federal grants helped it purchase its first hydrogen fuel-cell buses, the authority now has 22 such vehicles, making it the country’s fourth-largest hydrogen-powered transit fleet.

The vehicles emit only water vapor and warm air as exhaust, reducing air pollution in the neighborhoods where they run. But producing and transporting hydrogen for the fuel cells can be a significant source of climate emissions, which is why SARTA is partnering with energy company Enbridge and the Appalachian Regional Clean Hydrogen Hub, or ARCH2, on a plan to make the fuel on-site with solar power.

“So it will be green,” said Kirt Conrad, SARTA’s CEO, referring to the use of renewable energy to power the production of hydrogen by splitting water.

Currently, the transit agency imports hydrogen — made from natural gas without carbon capture — by truck from Canada. Such “gray” hydrogen emits about 11 tons of carbon dioxide per ton of hydrogen produced. President Donald Trump’s threatened tariffs against Canada could also affect the cost and supply of hydrogen available to SARTA, although specific impacts are still unclear.

SARTA had already worked with Dominion Energy on a compressed natural gas fueling station before Dominion’s Ohio utility company was acquired by Enbridge. When the Biden administration announced its regional clean hydrogen hub program in 2023, SARTA and the company joined others in Ohio, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania to pitch the ARCH2 hub. The hub was among seven selected by the Department of Energy in late 2023 and was awarded up to $925 million in funding last summer.

The plan is to install roughly 1,000 solar panels on about 10 acres of recently acquired land next to SARTA’s existing hydrogen fueling facility, said Conrad. That would generate up to 1 megawatt of electricity, powering an electrolysis facility that splits water into oxygen and hydrogen. Under the project’s current scope, the equipment would produce roughly 1 ton of hydrogen per day, enough to fuel 40 SARTA buses, Conrad added.

Details could change as the project progresses, according to Enbridge spokesperson Stephanie Moore. Enbridge would own the hydrogen production and storage equipment.

Conrad estimated that the whole project will cost around $15 million, about 70% of which would come from federal funding under the 2021 bipartisan infrastructure law and other grants. It’s unclear, though, whether the Trump administration will renege on those commitments, even those which have already been formally obligated under contract.

“ARCH2 receives funding for this project through a contract issued through the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations,” Moore said. “We have received no information outlining any modifications to that contract and therefore will continue moving forward on this project as planned.”

If the project can be completed, it will double SARTA’s supply of hydrogen, lower costs and emissions, and improve the transit system’s resiliency, Conrad said, noting that the agency has experienced occasional fuel delivery problems. Plus, domestic hydrogen production can support U.S. energy independence goals, he said.

A desire to switch to cleaner fuels and the costs per mile compared with diesel buses convinced SARTA to start buying fuel-cell buses in 2014. Today, it has 17 large buses and 5 smaller paratransit vehicles that run on fuel cells, which split hydrogen into protons and electrons and send them along separate paths. The electrons provide an electric current, while the protons wind up combining with oxygen to make water.

California has had fuel-cell buses on the road for more than two decades, and other places that have embraced the vehicles in recent years include Philadelphia’s Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority and Maryland’s Montgomery County.

Sean O’Leary, a senior researcher for the Ohio River Valley Institute, said the planned project by SARTA and Enbridge would cut greenhouse gas emissions compared with current practices.

“Green hydrogen is … a lot better than gray,” O’Leary said. However, he’s skeptical whether fuel-cell buses are the vehicles he would choose today for transit systems to reduce emissions. “I would personally rather see them go to electric buses or even biodiesel, both of which would reduce emissions more and cost a … lot less.”

Conrad said SARTA would have liked to have started out using green hydrogen, but it wasn’t available in the marketplace a decade ago. Now that the technology has advanced, he thinks it’s time to make the switch to a cleaner source of hydrogen.

“Sometimes an industry just needs time to evolve. And I think that’s what we’re starting to see now,” Conrad said.

If all proceeds well, SARTA anticipates on-site hydrogen production could start as soon as 2028.

PJM Interconnection, the organization that manages the transmission grid delivering electricity to about 65 million people from the mid-Atlantic coast to the Great Lakes, badly needs more power. In fact, its inability to connect projects languishing in its interconnection queues — most of them solar, wind, and batteries ready to replace closing coal-fired power plants — has spiked the cost of power, is threatening state clean power goals, and may put grid reliability at risk before decade’s end.

Last week, PJM won approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission for two dramatically different approaches to solving these problems. But clean energy companies and advocates say one of the plans is unfair and won’t work — and they’re hoping the grid operator will focus on the cleaner, faster, and more realistic alternatives at hand.

The plan critics take issue with, known as the Reliability Resource Initiative, allows PJM to fast-track some “dispatchable” generation resources — most likely, fossil gas–fired power plants — ahead of all the other projects that have been waiting for years to get connected, the vast majority of which are wind, solar, and batteries.

Power plant owners, utilities, and state regulators support the RRI. But opponents say it runs counter to fair and open grid access and market competition rules, could complicate already-clogged interconnection processes, and will likely fail to deliver the fast grid relief PJM is looking for.

At a FERC meeting last week, the RRI proposal passed by a 3-1 vote, with the fifth commissioner, Lindsay See, a Republican, abstaining. But only Mark Christie, a Republican who was named FERC chair by the Trump administration last month, voted in support of the plan without expressing reservations.

Willie Phillips and David Rosner, the two Democrats who voted in favor of RRI, said in a concurrence to the decision that their approval was a “one-time emergency measure” and that the plan is “not a substitute for a well-functioning interconnection process.” Judy Chang, a Democrat who voted against the plan, wrote in her dissenting statement that RRI “presents a risk of the worst of both worlds: It compromises the Commission’s open access principles with no guarantee it will resolve PJM’s reliability issue.”

One problem with RRI, Chang wrote, is that it seeks to fast-track the kind of power plants that are the hardest to build quickly: ”large generators, which are the most challenging to develop, acquire the necessary environmental permits, and obtain adequate material supplies and labor for construction.”

Another problem is that PJM’s methodology for choosing which projects get fast-tracked primarily rewards large ones, rather than prioritizing criteria like whether they can be brought online before 2030 or built at sites with existing “headroom” on PJM’s grid, even though those are “arguably the two most critical factors to meeting its identified reliability needs,” Chang wrote.

Critics have expressed similar concerns since PJM launched the RRI plan in October. The grid operator predicted that the plan could spur 10 gigawatts of new power plants by 2028. But industry observers say it’s highly unlikely that many gas-fired power plants could be built or connected that quickly.

Just getting the new gas turbines needed for these power plants can take four to five years given current order backlogs, according to industry experts. Last month, renewable energy developer NextEra Energy announced plans to build gas power plants with GE Vernova. But CEO John Ketchum noted in an earnings call that gas-fired generation projects not already well along in the procurement and construction process “won’t be available at scale until 2030 and then only in certain pockets of the U.S.”

Nor are large power plants likely to fit easily onto a PJM grid that’s already too congested to connect most projects, at least not without significant and costly grid upgrades, said Caitlin Marquis, managing director at clean energy trade group Advanced Energy United.

Letting up to 50 projects leap to the front of the line “could raise interconnection upgrade costs” for the many other projects that have been waiting to get onto the grid, she said.

Even the Electric Power Supply Association, a trade group representing companies that own and develop gas-fired power plants, has voiced reservations about the RRI plan. “All resources play a role in the evolving energy landscape; this limited tool is only necessary to address short-term interconnection queue bottlenecks and the current supply crunch,” Todd Snitchler, the group’s president and CEO, said in a statement last week. “We anticipate that PJM’s queue reform process will resolve these challenges, making such measures unnecessary in the future.”

All of these drawbacks make the RRI plan a nonstarter, critics say. But there are many other options that PJM could pursue, according to Marquis.

“Those solutions that don’t upend market expectations are the pathway you should take, rather than turning to a solution that’s going to have a lot of disruption and market risk and still yield uncertain outcomes,” she said.

The second PJM plan approved by FERC last week, known as Surplus Interconnection Service, is one such option. In simple terms, it lays out rules for existing projects to add new resources — like batteries to wind and solar farms — to provide more power when the grid needs it most.

That proposal won broad support from groups that have fought over RRI, including clean energy advocates and fossil fuel power plant owners who are usually at odds. The new plan, clean energy advocates point out, is much improved from PJM’s previous SIS regime.

“In the past, the surplus interconnection rules were very restrictive,” said Katie Siegner, a manager in the carbon-free electricity practice at think tank RMI. “Now it’s been opened up to be applicable to a much bigger set of resources.” For example, “we’ve heard from independent power providers that adding storage to existing or soon-to-be-operating renewables is now a real use case.”

In fact, an RMI analysis submitted as part of a FERC filing from environmental groups Sierra Club and Appalachian Voices calculated that by 2030, PJM projects using SIS could add between 5.3 GW and 13.2 GW of “unforced capacity” — a term for the amount of power available during times of peak grid demand that drive PJM’s resource-adequacy needs.

That’s not the only way PJM can unleash more power on the grid, Siegner said. Beyond SIS, PJM has put forward a bevy of ideas to deal with what it has described as a looming grid reliability crisis. Another proposal that’s won ample stakeholder support and is now awaiting FERC approval would let newly built resources more quickly reuse the grid connections left open at power plants, most of them coal-fired, that are now closing across the region.

According to RMI’s analysis, this “generator replacement interconnection” option could add from 3.3 GW to 10.2 GW of unforced capacity to PJM’s grid by 2030. That’s not just a neat way to replace dirty generation with much cleaner resources — RMI has estimated that the technique could enable up to 250 GW of clean energy across the country by 2032. It would also help resolve PJM’s core challenge of replacing power plants closing under state climate mandates or economic pressures.

Projects in Massachusetts, Minnesota, and North Carolina have all installed batteries that use the grid connections at shuttered coal-fired power plants. Environmental groups and Maryland state officials attempted to get PJM to consider such a plan to avoid paying a set of coal plants in Maryland to stay open past their planned closure dates, only to founder on PJM’s lack of a workable set of rules to allow this approach to move forward.

PJM won’t be trying something new if it pursues these pathways, Siegner added. The Midcontinent Independent System Operator and Southwest Power Pool, two grid operators that together manage grids covering or touching 18 states, have added nearly 7 GW of capacity using their own versions of surplus interconnection service, and a combined 13.3 GW of capacity through generator replacement, according to RMI’s analysis.

Finally, if PJM simply completes and executes long-promised reforms to its notoriously slow and backlogged process for managing its interconnection queue, that could make a big dent in its generation deficit, Siegner said. What’s more, PJM and all other U.S. grid operators are under FERC mandate to undertake interconnection reforms that should drive further improvements.

All of these changes will “allow resources to be fairly evaluated and interconnected faster,” she said. Taken together, they can more than make up the capacity shortfall PJM is forecasting for 2030 and that is spurring its RRI proposal.

Backers of fast-tracking gas-fired power plants aren’t against these other reforms. As Electric Power Supply Association’s Snitchler said in last week’s statement, “What matters most and what we hope to see going forward is a fair, efficient interconnection process that gives developers reasonable certainty while ensuring the grid has the power it needs—now and in the future.”

At the same time, the conflicts that have emerged over PJM’s menu of plans to solve its grid challenges match up with a broader political division between fossil fuel supporters and clean energy groups.

Last month, Republicans in Congress introduced bills that would require FERC to quickly review and decide on grid operator proposals that, like PJM’s RRI plan, push certain “dispatchable” power plants ahead of other projects in interconnection queues. The Electric Power Supply Association supports the legislation, which was introduced by lawmakers representing Ohio, North Dakota, and Indiana, three Republican-controlled states with policies that support fossil-fuel power plants.

At the same time, major grid failures during winter storms over the past four years have revealed that gas-fired power plants aren’t always able to provide the electricity that plans like these assume they will, said Sarah Toth Kotwis, a senior associate on the markets and grids team at RMI’s carbon-free electricity program.

PJM’s RRI proposal presumes that “larger resources are more likely to contribute to reliability. But in fact, we’ve seen time and time again that just because a resource is dispatchable doesn’t mean it’s reliable.”

Such proposals will likely face legal challenges. FERC’s decision last week rejected complaints by clean energy groups that PJM’s RRI plan violates legal precedent over making changes to existing rules and rates. But policies that privilege some types of power plants over others in the competitive markets managed by grid operators could certainly be seen as a violation of the “open access” principle that’s been core to federal electricity policy for decades, according to Rob Gramlich, president of consultancy Grid Strategies who previously held senior positions at FERC.

“For those who think they have an easy one-time fix or a way to get a quick solution here, maybe they’ve not been in court proceedings very often. But those don’t get resolved quickly, especially when you’re going after the core principle of FERC and Federal Power Act policy,” Gramlich said during a December webinar.

Gramlich didn’t dismiss the challenges that PJM and the country at large face in expanding power supply to serve data centers, factories, electric vehicles, and other drivers of growing electricity demand. But “I would suggest people might look for other ways to speed things up,” he said.

Consumer and clean energy advocates in Indiana are calling for a moratorium on new “hyperscale” data centers, which are driving a huge surge in power demand, until state leaders can study their potential impact on the electric grid and utility bills.

Indiana is projected to see a boom in data center construction in the coming years, with one recent report estimating that within a decade the facilities could consume more electricity than the state’s nearly 7 million residents combined. That projected demand has spurred utilities and state lawmakers to plan to ramp up natural gas–fired generation and build small modular nuclear reactors.

A state House committee this month approved a bill that would create tax breaks for small modular reactors on top of existing state tax breaks for data centers. That’s a risky approach, said Citizens Action Coalition program director Ben Inskeep. In addition to cutting state revenue, tax breaks have the potential to shift costs onto residential electricity customers, the consumer protection group warns.

The coalition demands that rather than scrambling to build more fossil-fuel and untested nuclear generation, lawmakers pass a moratorium on new hyperscale data centers so the issue can be studied further.

“The General Assembly should press pause on giving out additional subsidies to trillion-dollar big tech companies and ensure hardworking Hoosiers are protected and prioritized,” Inskeep said. “A moratorium strikes a reasonable balance, recognizing that we need time to understand the full impacts of the extraordinary data center growth already underway and make adjustments to current policies to protect consumers, taxpayers, and the environment while still allowing the possibility for sustainable data center growth in the future.”

Indiana is a particularly attractive state for new AI-focused data centers since it offers access to fiber optic cables, high-voltage transmission, and major information-demand regions like Chicago. The state has relatively cheap land and access to water needed for cooling.

It also draws power from both the PJM and MISO regional grids, meaning added electricity capacity and resilience, and is at relatively low risk of natural disasters that could interrupt electricity supply.

Meanwhile, a 2019 state law exempts large data centers from paying sales and use tax, including on the electricity they consume.

Two Microsoft data centers and an Amazon data center are in the works for Northwest Indiana near the shore of Lake Michigan, a region home to steel mills, a massive BP oil refinery, and other heavy industry. Google is planning a data center in Fort Wayne, also in northern Indiana, and Meta has proposed two data centers farther south in the state. Last year, a real estate and investment firm scrapped plans for a $1.3 billion data center in northern Indiana’s Chesterton amid intense opposition from residents.

While Meta says its data centers will be powered by 100% renewable energy, and Google and Microsoft also have ambitious clean energy goals, the companies have not provided specifics on clean energy for their Indiana centers. Plans filed with the state regulatory commission by two utilities — Northern Indiana Public Service Co., or NIPSCO, and Indiana Michigan Power, or I&M — indicate gigawatts of new natural gas–fired generation will be built to meet demand driven by data centers.

“Regardless of whatever accounting tricks Amazon and Google might try to claim, their data centers are very likely to be directly causing an enormous addition of fossil fuel resources,” said Inskeep, echoing analyses by experts in other states.

Google and Amazon did not return requests for comment for this story, and a Microsoft spokesperson declined to comment. Utilities NIPSCO and I&M did not return requests for comment.

Plans already filed by utilities show major increases in natural gas–fired generation. In testimony filed in December with the state’s regulatory commission, I&M consultant Caleb Loveman noted that the utility expects its Indiana load to grow by 4.4 GW by 2030 largely because of data centers. The utility is proposing scenarios including new natural gas–fired generation and shifting power from Michigan to its Indiana customers through an ongoing regulatory process. NIPSCO has proposed more than 3 GW in new natural gas generation over the next decade, according to regulatory filings.

There are currently no nuclear reactors in Indiana, and critics note that small modular reactors are a relatively untested technology that has not been deployed at commercial scale.

Meanwhile, nationwide, data center demand has meant coal plants converting to natural gas generation or staying open longer and continuing to burn coal.

Utility Hoosier Energy announced plans to close the Merom coal plant in Indiana in 2023 but then sold it to a company called Hallador Energy that is keeping the plant open and reportedly making a deal with a data center developer.

Experts note that ensuring data centers are actually using renewable energy around the clock is extremely difficult since they draw energy from fossil fuel–heavy local grids at times when the sun isn’t shining and wind isn’t blowing. Indiana got 45% of its electricity from coal in 2023, according to the Energy Information Administration, making it the nation’s second-largest coal consumer after Texas.

“We’re unilaterally opposed to data centers, especially hyperscaler ones,” said Ashley Williams, executive director of Just Transition Northwest Indiana. She described data centers as “an investment in an extractive economy, doubling down on it, when what we’re advocating for is regenerative and renewable energy.”

An analysis by Ivy Main, a lawyer and renewable energy co-chair for Sierra Club’s Virginia chapter, found that Amazon’s data centers in Virginia — the world’s largest data center market — have likely increased the burning of fossil fuels in the region, despite the company’s claims to have reached 100% renewable energy worldwide.

“The self-styled climate hero turns out to be a climate parasite,” Main wrote in an opinion piece for Virginia Mercury. A Virginia legislative audit predicts data centers could increase the state’s electricity demand almost three-fold between 2023 and 2040.

The situation is similar in Wisconsin and Illinois, where a data center boom is keeping fossil-fuel generation running and making it harder for the states to meet their ambitious clean energy goals. Customers are better insulated from possible bill increases in Illinois, where the deregulated energy market means power companies can’t directly charge ratepayers for building new power plants.

Nationwide, states have adopted tax breaks and other incentives to attract data centers. At least 16 states offer sales tax exemptions, and some also offer property tax breaks, according to Data Center Dynamics, an industry publication. A recent Policy Matters Ohio study found that local sales tax breaks given to Microsoft, Google, and Amazon for data centers could have totaled almost $1.6 billion over the last two years. States including Virginia and Alabama make tax breaks contingent on wage and job creation requirements.

Along with exempting data centers from sales and use tax, Indiana’s 2019 law allows individual counties and municipalities to offer property tax breaks. In 2023, Fort Wayne, Indiana, approved a more than $55 million property tax break over 10 years for a data center with the code name Project Zodiac, to be built by a mystery developer that turned out to be Google. The South Bend Tribune estimated that a proposed Amazon data center’s property tax abatements could eventually reach $4 billion.

Data center opponents say subsidies are unnecessary and unhelpful for the local economy. Kasia Tarczynska, senior research analyst at the national corporate watchdog organization Good Jobs First, during a webinar cited a statement from Microsoft executive Bo Williams in The New York Times that subsidies have not been a determining factor in where the company locates data centers.

Google, Amazon Web Services, and Microsoft signed an agreement in November with I&M, Indiana’s Office of Utility Consumer Counselor, and Citizens Action Coalition meant to make sure that the cost of new generation and grid upgrades isn’t unduly passed on to regular customers.

Under the agreement, in I&M territory these companies developing data centers must provide collateral during early years of operation, sign contracts of at least 12 years, and agree to pay at least 80% of their expected demand each month. Advocates consider such safeguards especially important in the new world of AI-driven data centers because if a facility’s energy demands end up being much lower than expected or if it closes prematurely, customers could end up paying for stranded assets — grid and generation investments made by the utility.

I&M’s large industrial customers previously had contracts but with much shorter minimums and lower payment thresholds.

The agreement creates a program where the companies can voluntarily invest in clean energy. The companies also agreed to pay half a million dollars each annually for five years into a fund that helps low-income residents access energy programs like weatherization.

Inskeep said that while the Citizens Action Coalition is frustrated at lawmakers’ enthusiasm for data centers and small nuclear reactors, the advocates do support a state bill introduced in January that would demand more transparency about data centers’ energy use. The bill would require that local governments review projected energy and water usage and other impacts before approving permits for a data center. Once a data center is operating, it would need to publicly report its energy use each quarter.

Inskeep said this bill would be a good start, and the coalition thinks even more study should be done during a moratorium.

“We think such a study should analyze trends and impacts, include opportunities for stakeholder involvement and public comment, and identify potential policy solutions,” he said.

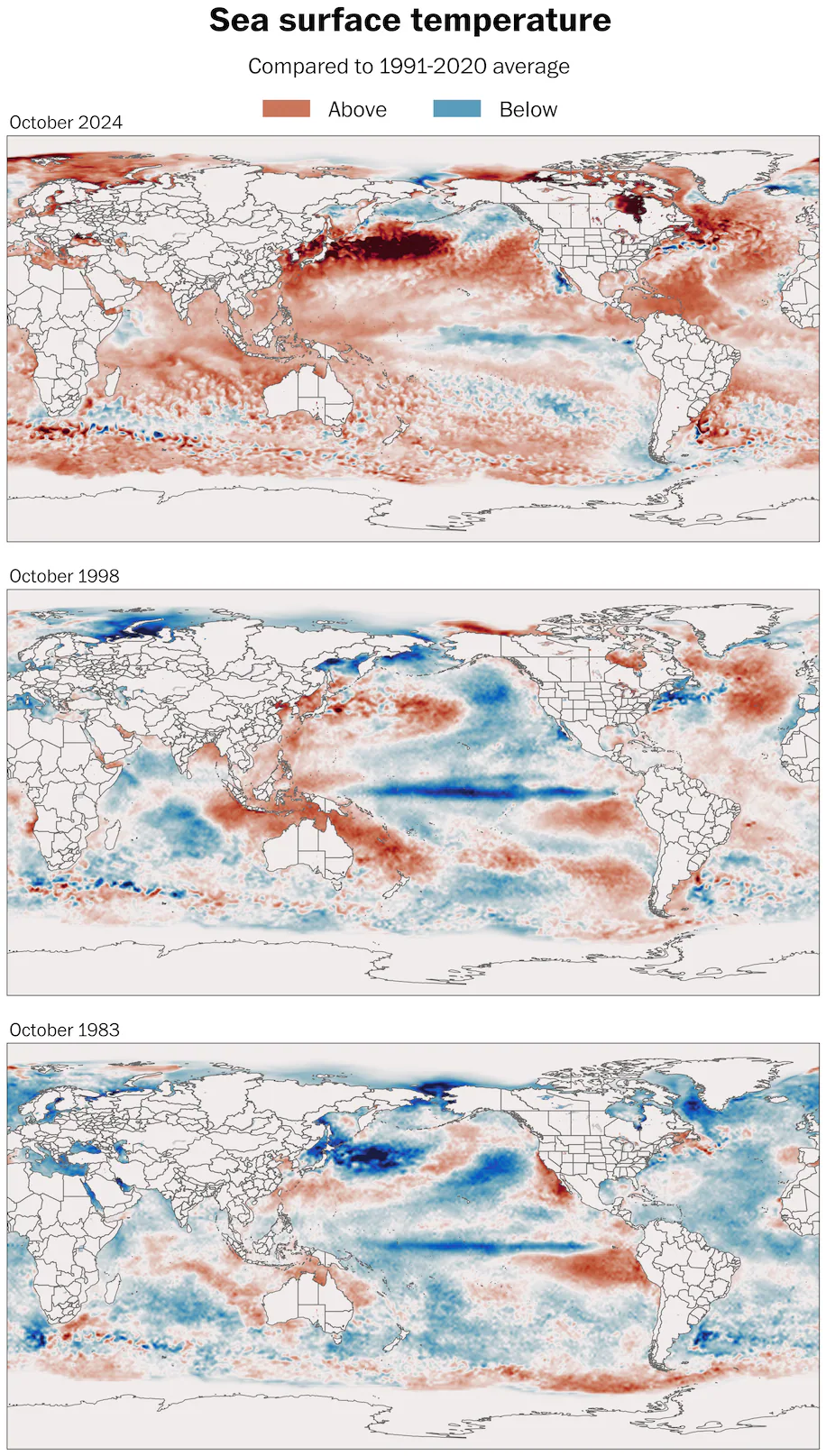

As 2023 came to a close, scientists had hoped that a stretch of record heat that emerged across the planet might finally begin to subside this year. It seemed likely that temporary conditions, including an El Niño climate pattern that has always been known to boost average global temperatures, would give way to let Earth cool down.

That didn’t happen.

Instead, global temperatures remain at near-record levels. After 2023 ended up the warmest year in human history by far, 2024 is almost certain to be even warmer. Now, some scientists say this could indicate that fundamental changes are happening to the global climate that are raising temperatures faster than anticipated.

“This shifts the odds towards probably more warming in the pipeline,” said Helge Goessling, a climate physicist at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany.

One or two years of such heat, however extraordinary, doesn’t alone mean that the warming trajectory is hastening. Scientists are exploring a number of theories for why the heat has been so persistent.

The biggest factor, they agree, is that the world’s oceans remain extraordinarily warm, far beyond what is usual — warmth that drives the temperature on land up, as well. This could prove to be a temporary phenomenon, just an unlucky two years, and could reverse.

“Temperatures could start plummeting in the next few months and we’d say it was just internal variability. I don’t think we can rule that out yet,” said Zeke Hausfather, a climate scientist at Berkeley Earth. But he added, “I think signs are certainly pointing toward fairly persistent warmth.”

But some scientists are worried the oceans have become so warm that they won’t cool down as much as they historically have, perhaps contributing to a feedback loop that will accelerate climate change.

“The global ocean is warming relentlessly year after year and is the best single indicator that the planet is warming,” said Kevin Trenberth, a distinguished scholar with the National Center for Atmospheric Research.

Other factors are temporary, even if they leave the world a bit hotter. One important one, scientists say, is that years of efforts to clean up air pollutants are having an unintended consequence — removing a layer in the atmosphere that was reflecting some of the sun’s heat back into space.

Whatever the mix of factors or how long they last, scientists say the lack of clear explanation lowers their confidence that climate change will follow the established pattern that models have predicted.

“We can’t rule out eventually much bigger changes,” Hausfather said. “The more we research climate change, the more we learn that uncertainty isn’t our friend.”

Experts had been counting on the end of El Niño to help reverse the trend. The routine global climate pattern, driven by a pool of warmer-than-normal waters across the Pacific, peaked last winter. Usually about five months after El Niño peaks, global average temperatures start to cool down.

Often, that’s because El Niño is quickly replaced with La Niña. Under this pattern, the same strip of Pacific waters become colder than normal, creating a larger cooling effect on the planet. But La Niña hasn’t materialized as scientists predicted it would, either.

That leaves the world waiting for relief as it confronts what is forecast to be its first year above a long-feared threshold of planetary warming: average global temperatures 1.5 degrees Celsius warmer than they were two centuries ago, before humans started burning vast amounts of fossil fuels. (Formally crossing this threshold requires at least several years above it.)

The year 2023 is the current warmest year on record at 1.48 degrees Celsius above the preindustrial average. However, 2024 is expected to be at least 1.55 degrees, breaking the record set the year before. Last year’s record was further above the expected track of global warming than scientists had ever seen, by a margin of more than three tenths of a degree. This year, that margin is expected to be even larger.

While changes in temperatures of a degree or less may seem small, they can have large effects, Trenberth said.

Like “the straw that breaks the camel’s back,” he said.

That includes increasing heat and humidity extremes that are life-threatening, changing ocean heat patterns that could alter critical fisheries, and melting glaciers whose freshwater resources are key to energy generation. And scientists say if the temperature benchmarks are passed for multiple years at time, storms, floods and droughts will increase in intensity, too, with a host of domino effects.

Compared with past years when El Niño has faded, the current conditions are unlike any seen before.

A look at sea surface temperatures following three major El Niño years — 2024, 1998 and 1983 — reveal that a La Niña-like pattern was evident in all three years, with a patch of cooler-than-average conditions emerging in the equatorial Pacific Ocean.

But in 2024, the patch was narrow, unimpressive and dwarfed by warmer-than-average seas that cover most of the planet, including parts of every ocean basin.

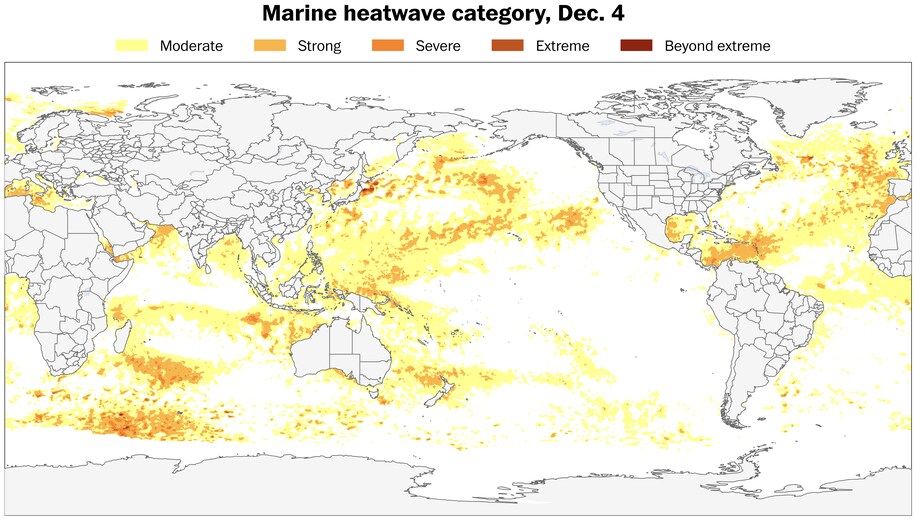

Known as marine heat waves, these expansive blobs of unusual oceanic heat are typically defined as seas being much warmer than average, in the highest 10 percent of historical observations, across a wide area for a prolonged period. Strong to severe marine heat waves are occurring in the Atlantic, much of the Pacific, the western and eastern Indian Ocean, and in the Mediterranean Sea.

In October, ocean temperatures at that high threshold covered more than a third of the planet. On the other end, less than 1 percent of the planet had ocean temperatures in the lowest 10 percent of historical values.

Warm and cold ocean temperature extremes should more closely offset each other. But what’s happening is a clear demonstration that oceans, where heat accumulates fastest, are absorbing most of Earth’s energy imbalance. Warm extremes are greatly exceeding cold ones.

That’s a problem because what happens in the ocean doesn’t stay in the ocean.

Because ocean water covers more than 70 percent of Earth, what happens there is critically important to temperatures and humidity on land, with coastal heat waves sometimes fueling terrestrial ones. Weather systems can sometimes linger, producing persistent sunny and wind-free days and bringing ideal conditions for marine heat wave development. These systems can sometimes straddle the land and the ocean, leading to a connected heat wave and transporting humidity.

Trenberth said increasing heat in the oceans, particularly the upper 1,000 feet, is a major factor in the relentless increases in average surface temperatures around the world.

And changes in ocean heat content can affect not just air temperatures, but sea ice, the energy available to storms and water cycles across the planet.

Research has begun to unpack what else may be triggering such changes in global heat.

One recent study found that a reduction in air pollution over the world’s oceans may have contributed to 20 to 30 percent of the warming seen over the North Atlantic and North Pacific, said Andrew Gettelman, a scientist at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory and the study’s lead author.

Restrictions on sulfur content in the fuels used by shipping liners, put in place in 2020, have dramatically reduced concentrations of sulfur dioxide particles that tend to encourage cloud formation. Though it means lower pollution levels, with fewer clouds, more solar radiation is hitting the oceans and warming them.

A study released Tuesday found that a decline in cloud cover likely contributed to perhaps 0.2 degrees Celsius in previously unexplained warming that hit the planet last year. Goessling and colleagues think that was the product of cleaner shipping emissions, as well as a positive feedback loop in which warming close to Earth’s surface leads to reduced cloud cover, which leads to even more warming.

The study found that in 2023, planetary albedo — the amount of sunlight reflected back into space by light-colored surfaces including clouds, snow and ice cover — may have been at its lowest since at least 1940.

There have also been questions about the roles other factors may be playing, such as an increase in stratospheric water vapor after a 2022 volcanic eruption.

But Earth’s systems are so complex that it’s been impossible to parse what exactly is happening to allow the surge in global temperatures to persist for so long.

“Is this just a blip, or is this actually an acceleration of the warming?” Gettelman said. “That’s the thing everyone is trying to understand right now.”

This year is widely expected to be the warmest year on record, driven largely by the huge stores of ocean heat.

And for now, seasonal model guidance keeps the foot on the accelerator into early 2025, as far as widespread warmer-than-average seas go.

Because of record ocean heat and global temperatures, atmospheric circulation patterns, jet streams and storm tracks across the planet will change. Temperature records will continue to be set.

How big these changes are partly depends on how much warming occurs in the year ahead. But that is unclear because the cooling that usually follows El Niño still hasn’t arrived.

.webp)

It’s possible that normal planetary variations are playing a bigger role than scientists expect and that temperatures could soon begin to drop, said Hausfather, who also works for the payments company Stripe.

Even without the cooling influence of a La Niña, a stretch under neutral conditions, with neither a La Niña nor an El Niño, should mean some decline in global average temperatures, he said.

At the same time, if this year’s unusual planetary warmth doesn’t slow down into 2025, there would be nothing to prevent the next El Niño from sending global temperatures soaring — the starting point for the next El Niño would be that much higher. Whether that happens later in 2025 remains to be seen.

But the lack of clarity isn’t a promising sign when some of the most plausible explanations allow for the most extreme global warming scenarios, Hausfather said.

“The fact that we don’t know the answer here is not necessarily comforting to us,” he said.

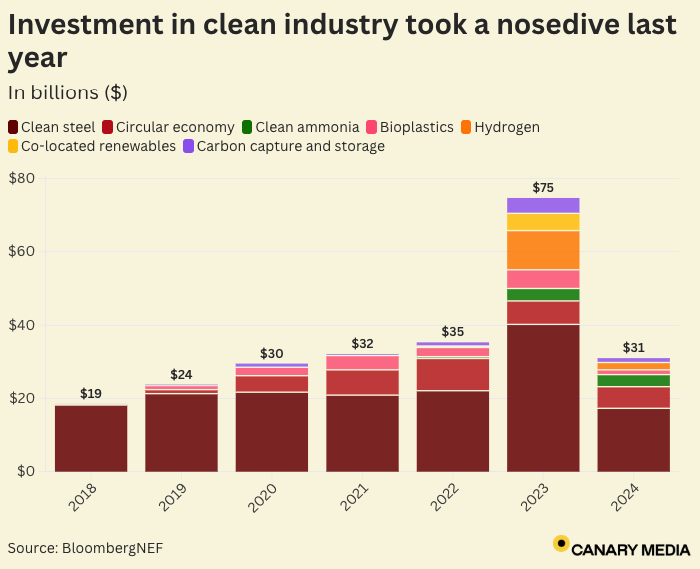

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

Global investment in efforts to decarbonize heavy industries totaled just $31 billion in 2024, marking a tough year for areas including hydrogen-based steelmaking and carbon capture and storage.

Money for clean industry–related projects fell by nearly 60% last year compared with 2023 — even as investment in the broader energy transition grew to a record $2.1 trillion in 2024, per BloombergNEF.

The diverging outcomes reflect a “two-speed transition” emerging in markets around the world, according to the research firm. The vast majority of today’s energy-transition investment is flowing to more established technologies, such as renewable energy, electric vehicles, energy storage, and power grids.

Meanwhile, efforts to slash planet-warming emissions from heavy industrial sectors — including steel, ammonia, chemicals, and cement — continue to face more fundamental challenges around affordability, maturity, and scalability.

Clean steel projects took the biggest hit in financial commitments, with investment falling to around $17.3 billion in 2024, down from $40.2 billion the previous year, BNEF found.

The category includes new furnaces that can use hydrogen instead of coal to produce iron for steelmaking. Green hydrogen made from renewables remained costly and in scarce supply, leading producers like Europe’s ArcelorMittal to delay making planned investments in hydrogen-based projects. Electric arc furnaces — which turn scrap metal and fresh iron into high-strength steel using electricity — are also considered clean steel projects. Mainland China saw a sharp decline in funding for new electric furnaces as steel demand withered among its automotive and construction industries.

Investment held flat in 2024 for new facilities that use “low-emissions hydrogen” instead of fossil gas to produce ammonia, a compound that’s mainly used in fertilizer but could be turned into fuel for cargo ships and heavy-duty machinery. However, funding declined last year for circular economy projects that recycle plastics, paper, and aluminum, as well as for bio-based plastics production.

BNEF found that, unlike in 2023, few developers of new clean steel and ammonia facilities allocated capital for “co-located” hydrogen plants and renewable energy installations. Likewise, fewer commitments were made to install carbon capture and storage units on polluting facilities like cement factories and chemical refineries.

Whether these investment trends will continue in 2025 depends largely “on a few crucial policy developments in key markets,” Allen Tom Abraham, head of sustainable materials research at BNEF, told Canary Media.

In the United States, companies are awaiting more clarity on the future of federal incentives for industrial decarbonization. The Biden administration previously directed billions of dollars in congressionally mandated funding to support cutting-edge manufacturing technologies and boost demand for low-carbon construction materials — money that is now entangled in President Donald Trump’s federal spending freeze.

Investors are also watching to see what unfolds this month in the European Union. Policymakers are poised to adopt a “clean industrial deal” to help the region’s heavily emitting sectors like steel, cement, and chemicals to slash emissions while remaining competitive. And in China, the government is drafting new rules aimed at easing the country’s overcapacity of steel production, which could impact the deployment of new electric arc furnaces.

“Positive developments on these initiatives could boost clean-industry investment commitments in 2025,” Abraham said.

The recent cancellation of a Massachusetts networked geothermal project isn’t dampening enthusiasm for the emerging clean-heat strategy.

National Grid said this month it has abandoned a planned geothermal system in Lowell, Massachusetts, due to higher-than-expected costs. The news disappointed advocates who see networked geothermal as an important tool for transitioning from natural gas heat, but they pointed to many more reasons for optimism about the concept’s momentum.

The nation’s first utility-operated neighborhood geothermal network, a loop serving 36 buildings in the Massachusetts city of Framingham, is performing well and seeking to expand. It’ll soon be joined by a surge of pilot projects being developed across the country, testing different models and accelerating the learning curve. And a recent report forecasts as much as $5.2 billion in potential savings from leaning more heavily on geothermal energy than on air-source heat pumps.

“This is very promising,” said Ania Camargo, associate director of thermal networks for the Building Decarbonization Coalition. “Networked geothermal makes a lot of sense as a transition strategy.”

The idea for utility-operated networked geothermal systems, often also referred to as thermal energy networks, originated in Massachusetts. The concept grew out of conversations about the environmental and public health dangers posed by aging and increasingly leaky natural gas pipes.

In 2014, the state passed a law requiring gas companies to create plans to replace these leaky pipelines. These plans, however, are projected to cost nearly $42 billion to execute. Climate advocates began to question the wisdom of investing so much money in fossil fuel infrastructure when state policy was simultaneously pushing for electrification and renewable energy. At the same time, air-source heat pumps were catching on, a growing trend that would leave fewer and fewer gas consumers to foot the bill for pipeline repairs.

In 2017, Massachusetts clean energy transition nonprofit HEET proposed a solution: networked geothermal. The systems would be based on well-established geothermal technology, which circulates liquid through pipes that run deep into the ground, extracting thermal energy from the earth and carrying the heat back up to warm buildings. The same principle can provide cooling as well, transporting heat away from buildings and returning it to the ground.

Thermal energy networks scale up the process, connecting many buildings to one geothermal loop, allowing heating and cooling to be delivered to homes in much the same way gas and electricity are. At the same time, they offer a new business model for gas utilities grappling with states’ efforts to transition away from fossil fuels. Utilities liked the idea and jumped on board.

In 2023, the first two such systems broke ground in Massachusetts: National Grid launched one in Lowell, and Eversource began work on a system in Framingham.

The University of Massachusetts Lowell, which was a partner in National Grid’s now-canceled project, hopes to use the engineering and design work developed for the project as the basis for a future network, said Ruairi O’Mahony, senior executive director of the university’s Rist Institute for Sustainability and Energy.

Even the cancellation provides valuable insight by providing a case study of what didn’t work, said Audrey Schulman, executive director of HEETlabs, a climate solutions incubator that spun off from HEET. In this case, the problems included participating homes spread too far from each other and issues with the field where the boreholes were to be drilled. “We’re on an even better arc,” Schulman said. “If there’s a mistake made, we have to correct for it. We can’t have people paying for things that cost too much.”

Meanwhile, the Framingham network began hooking up its first customers in August 2024 and now has about 95% of its anticipated load up and running, said Eric Bosworth, clean technologies manager for Eversource. The system is performing well, keeping customers warm even when a recent cold snap dropped temperatures down to 6 degrees Fahrenheit, he said.

Plans are already underway to expand the system. The U.S. Department of Energy in December awarded Eversource, the city of Framingham, and HEET a $7.8 million grant to develop a second geothermal loop to be connected to the first network, in the process generating valuable information about expanding and interconnecting geothermal systems. The grant is still under negotiation with the federal agency, so it is unclear what the final terms will be. Still, Eversource hopes to have the second system installed in 2026.

“What we’re trying to prove out with Framingham 2.0 is, as we expand on an existing system, that we can do it more efficiently and bring down that cost per customer,” Bosworth said.

The widespread interest in networked geothermal systems within Massachusetts and throughout the U.S. is also promising, Camargo said. In Massachusetts, National Grid is continuing work on a different geothermal network pilot serving seven multifamily public housing buildings in the Boston neighborhood of Dorchester. Last year, HEET, with support from the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center, awarded $450,000 in grants to 13 communities to conduct geothermal feasibility studies. And a climate law passed in Massachusetts last year authorizes utilities to undertake networked geothermal projects without getting specific regulatory approval to veer out of their natural-gas lane.

New York has also embraced the idea with enthusiasm. In 2022, the state enacted a law allowing utilities to develop geothermal networks and requiring regulators to come up with guidelines for these new systems. So far, 11 projects have been proposed using a variety of approaches that will provide takeaways for the developers of future geothermal networks, Camargo said.

“New York is amazing,” she said. “They’re doing things in different ways to innovate.”

Across the country, between 22 and 27 geothermal networks have been proposed to utility commissions in Colorado, Maryland, Minnesota, and other states, she said. Eight states have passed legislation supporting utility construction of thermal energy networks, according to Building Decarbonization Coalition numbers, and another four or five are expected to file bills this year, Camargo said.

A report prepared by Synapse Energy Economics for HEETlabs and released last month concludes that geothermal networks offer significant financial benefits when compared with using air-source heat pumps. The analysis found that each system roughly the size of the Framingham network could generate from $1.5 million to $3.5 million in economic benefits, including avoided transmission and distribution costs from lowering peak demand. If 1,500 geothermal networks came online in Massachusetts, the savings could hit $5.2 billion, the analysis calculates.

These savings could be used to subsidize building retrofits, making the homes and offices connected to a geothermal network highly energy efficient to optimize the impact of the ground-source heat pumps, Schulman said.

Even with gathering momentum, challenges remain to the widespread adoption of geothermal networks.

Retrofitting buildings on the network is perhaps the thorniest, particularly in the Northeast where much of the building stock is older and draftier, said both utilities and advocates. In Framingham, an individual efficiency plan had to be created for each home and structure on the loop, a time- and money-consuming process. Going forward, a more streamlined, standardized procedure will likely be necessary, Camargo and Bosworth both said.

“Utilities have not traditionally worked inside the building, so who does it and who pays for it is something that still needs to get worked out,” Camargo said.

Cost is another concern, as the terminated Lowell project demonstrates. However, costs are likely to come down as engineers and installers gain experience in the process and develop smoother supply chains, Schulman said. The second loop planned for Framingham is already likely to be half the amount of the initial system, she said.

As these challenges are worked through, it is vital for Massachusetts to approach its role as a leader in geothermal networks with care, Schulman said.

“We need to think ahead and do this in an efficient and thoughtful way and show the country how it can be done,” she said.

The city of Minneapolis is retooling a decade-old partnership with its gas and electric utilities in response to criticism that it hasn’t done enough to help the city reach its climate goals.

The Clean Energy Partnership was established in 2014 as part of the city’s last round of utility franchise agreements with Xcel Energy and CenterPoint Energy. The agreements authorize utilities’ use of public right-of-way, often in exchange for fees or meeting other terms or conditions from the city.

A little over a decade ago, Minneapolis was among the first U.S. cities to view utility franchise agreements as a potential tool to leverage for climate action. Some advocates at the time had been pressuring the city to study creating a municipal utility to accelerate clean energy, and the partnership emerged as a compromise to give the city more say in the utilities’ operations.

Former City Council member Cam Gordon, who represented southeast Minneapolis in 2014 when the council approved the partnership, is one of the critics who say the initiative “never realized its potential.” Instead, it mainly served as “a government relations and promotional PR tool to allow [elected officials] and the utilities to feel like we’re doing something,” he said.

The City Council is set to approve new franchise agreements this week, and they include an updated memorandum of understanding for the Clean Energy Partnership that will require regular reporting on key performance indicators, new utility-specific emission goals, energy conservation, and service reliability in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

Spokespeople for both companies said they welcome the planned changes and that the agreement reflects their interest in working with city leaders on shared clean energy goals.

Since the partnership went into effect in 2015, it has brought together representatives of the utilities, the City Council, and the mayor’s office once per quarter to talk about efforts to reduce emissions in the city. Clean energy advocates and other stakeholders sit on an advisory committee but do not have a formal seat on the partnership’s governing board.

Minneapolis City Council Vice President Aisha Chughtai, who represents the council on the partnership board, expressed frustration about the lack of follow-through from utilities. “Sitting in a meeting and nodding along is one thing. Changing your actions is another,” she said.

By the partnership’s own measures, it has failed to make significant progress on five out of the city’s seven major climate goals. The city is on track with its target to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from municipal operations but behind pace with its goals related to citywide, residential, commercial, or industrial emissions.

Going forward, the partnership board will continue to meet quarterly, but instead of revolving around city climate goals, each utility will be expected to hit specific targets within Minneapolis’s borders. CenterPoint will commit to reducing emissions from natural gas use by at least 20% by 2035 compared with 2021.

“I think it’s progress,” said council member Katie Cashman, who represents an area west of downtown. The gas utility’s target is “a very meager, insufficient goal, but it is a goal nonetheless, and they haven’t done this in any other city.”

CenterPoint agreed to send a more senior executive to attend the quarterly partnership meetings, though Xcel did not. The utilities also rejected the city’s proposal to hire an outside administrator to manage the partnership.

City leaders believe the new agreement does a better job of setting expectations, but Minneapolis will still lack formal leverage over the utilities if they fail to make progress. The agreement does not contain any penalties for failure to follow through, and the next window to renegotiate isn’t until 2035 when the franchise agreement comes back up for renewal.

Luke Hollenkamp, the city’s sustainability program coordinator, said data reported through the partnership allows the city to make course corrections in its climate work.

“We can see what’s working, what’s not working, and also see where we need to invest more time,” he said.

Xcel Energy’s spokesperson said the partnership has led to successes, noting that citywide emissions from electricity have declined and that Minneapolis met its goal of powering city operations with 100% renewable electricity in 2023 by participating in Xcel’s Renewable*Connect program.

CenterPoint said it has invested nearly $61 million in energy efficiency programs in Minneapolis since 2017, saving residents $25 million in energy costs while reducing 245,000 metric tons of emissions. The utility also developed an on-bill financing program advocated by clean energy activists and others.

Despite the partnership’s imperfections, current and former city officials said it’s better to keep it in place as part of the new franchise agreements than to let it dissolve.

“We’re ramping up our trajectory [to cut emissions],” Cashman said. “We’re setting an example of how other cities can lead on climate action.”

The City Council’s climate and infrastructure committee approved the new agreements on Feb. 6; the full council is set to vote on them Feb. 13.

Clean energy installations in the U.S. reached a record high last year, with the country adding 47% more capacity than in 2023, according to new research by energy data firm Cleanview.

Boosted by tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act and the plummeting costs of renewable technologies, developers added 48.2 gigawatts of utility-scale solar, wind, and battery storage capacity in 2024. In total, carbon-free sources including nuclear accounted for 95% of new power capacity built in the U.S. last year; solar and batteries alone made up 83%.

The report finds that developers are not only building more projects but bigger ones, too. In 2024, companies built 135 solar, wind, and storage facilities with 100 megawatts or more of capacity, continuing a trend of clean energy megaprojects around the country.

Despite the growth of renewables, fossil fuels — mostly gas — still generated more than half of the U.S.’s electricity last year. Carbon-free sources including nuclear produced just over 40% of power.

This year, renewables will continue growing but at a slower pace, the report says. Based on developer projections, the U.S. could add 60 GW of large-scale clean power capacity in 2025. That would be a 26% jump from the previous year, but it’s only possible if the industry can maintain momentum despite headwinds from the Trump administration.

Solar led the way last year and is expected to do the same this year.

In 2024, the U.S. added a new record of 32.1 GW worth of utility-scale solar capacity. That’s a 65% increase from 2023, when the country added 19.5 GW of utility-scale solar. Most new solar was built in Texas, which added 8.9 GW worth of the clean energy source, followed by Florida, which built 3 GW and outpaced California for the first time. Arkansas, Missouri, and Louisiana each saw rapid growth in solar, adding hundreds of MW of capacity where relatively little existed before.

Developers expect to add 33 GW of utility-scale solar to the grid in 2025, which would represent a 3% year-on-year growth, the report finds. The U.S. Energy Information Administration, meanwhile, said in late January that it expects solar installations to decline to 26 GW this year.

Continued progress for solar — and for any clean energy deployments — will depend heavily on the Trump administration.

President Donald Trump has already stalled clean energy and infrastructure projects nationwide by attempting to halt hundreds of billions of dollars in congressionally authorized funding — a move that experts say is illegal and has been struck down by federal courts. Some Republican members of Congress have also threatened to roll back clean energy tax credits under the Inflation Reduction Act that are key to enduring growth in the renewables sector.

For utility-scale solar, “uncertainty around the Trump administration’s energy agenda and the future of the IRA will cause the segment to stagnate, despite extremely high demand from data centers,” analysts at Wood Mackenzie wrote in January.

The political picture is even more grim for the U.S. wind sector, which has already seen years of declining installations and now faces relentless attacks from Trump.

For several years now, the wind industry has faced challenges including a lack of long-distance transmission lines to transport electricity from far-flung areas in the middle of the country to urban centers. Supply chain woes and inflation have also led to a spate of canceled offshore wind projects in the Northeast.

In 2024, the U.S. added 5.1 GW of utility-scale wind, including its first commercial offshore wind farm, marking a 23% drop from 2023 and the fourth year in a row of falling annual installations. Texas alone accounted for 42% of the country’s new wind capacity in 2024, bringing 2.1 GW online.

Developers expect to add 9.2 GW of wind capacity this year, and 6.1 GW are already under construction or waiting to come online, according to the Cleanview report. If that happens, wind capacity additions would increase by 79% this year.

But that’s a big if. Trump has vowed that “no new windmills” will be built during his presidency and has taken aim at offshore wind in particular — a sector that on paper is set to give wind installations a big boost this year. It remains to be seen whether these under-construction projects will be able to forge ahead as planned despite political headwinds.

Battery storage could be more of a bright spot. Its growth, already fast, is set to accelerate this year.

Last year, the U.S. added 10.9 GW of battery storage capacity, a 65% year-on-year increase that surpassed the previous 56% leap in 2023. California and Texas brought the most grid storage online, building 3,152 MW and 2,832 MW of capacity respectively.

In 2025, storage developers expect to add 18.1 GW of capacity, which would equal a 68% jump from 2024. Based on projections, Texas will overtake California as the nation’s leading energy storage market by adding 7 GW of capacity this year, Cleanview found.

The battery buildout has been propelled in part by declining prices, but even energy storage hasn’t escaped Trump’s assault on renewables. The administration’s tariffs on Chinese imports are expected to negatively impact the industry, which relies on batteries manufactured in China.