As the Trump administration attempts to block billions of dollars in federal funds for electric vehicle charging, an Illinois utility is moving forward with a massive investment to promote wider EV adoption.

At a press conference last Thursday ahead of the 2025 Chicago Auto Show, ComEd announced $100 million in new rebates designed to boost EV fleet purchases and charging stations across northern Illinois. The program helps meet the mandate for the state’s Climate and Equitable Jobs Act, which calls for 1 million EVs on the roads by 2030.

Of the $100 million, $53 million is available for business and public-sector EV fleet purchases, while nearly $38 million is designated to upgrade infrastructure for non-residential charger installations. An additional nearly $9 million is intended for residential charging stations.

The money is in addition to $87 million announced last year for similar incentives.

Funding for the rebate programs comes from distribution charges and “has nothing to do” with the federal government, Melissa Washington, senior vice president of customer operations and strategic initiatives at ComEd, said during an interview. This means that there is no risk of withholding or reductions from the Trump administration.

Washington anticipates continued high levels of interest and engagement in the programs.

“Based upon what we saw last year, there was a quick demand. Applications came right away the minute we opened it up. I would imagine people will be going on [ComEd’s website] and immediately trying to see what we have available for them,” Washington said.

Since launching its EV rebate program last year, ComEd has funded projects in more than 300 ZIP codes, including nearly 3,500 residential and commercial charging ports, and provided funding for municipalities, businesses, and school districts to purchase more than 200 new and pre-owned EV fleet vehicles. The utility designated more than half the available rebate funds for low-income customers and projects in environmental justice communities.

ComEd also partners with the Chicago-area Metropolitan Mayors Caucus on the EV Readiness Program, which helps local governments create ordinances and safety and infrastructure plans to accommodate the growing demand for EVs in their communities. Since its initiation, more than 41 northern Illinois municipalities have participated in the program.

The importance of utility funding for the rebate programs was highlighted by Susan Mudd, senior policy advocate for the Environmental Law and Policy Center, who noted that a St. Louis-area school district is still waiting on 21 electric school buses that had been promised and ordered. The district has been unable to access the online portal to receive its federal funding, due to an executive order issued by the Trump administration.

“During the last four years, the federal government was a reliable partner with policies and programs that helped propel electric vehicle production and implementation and updated standards to save consumers money while cleaning up the air,” Mudd said at the press conference. “That order has already meant that students who would already be riding quiet zero-emission buses are still on old, dirty diesel ones, and the business that was to deliver them can’t get paid.

“While the new administration is willing to sacrifice the health of people across the U.S. and the world, thankfully, we in Illinois can continue to improve things,” Mudd said.

Canary Media’s Electrified Life column shares real-world tales, tips, and insights to demystify what individuals can do to shift their homes and lives to clean electric power.

Andrew Garberson isn’t worried about his electric vehicle handling cold winters.

He recently drove his EV to the gym when the temperature where he lives in Des Moines, Iowa, was a biting 4 degrees Fahrenheit. A polar vortex had brought a brutal wind, “the kind that whistles in the cracks of the car doors when you drive.”

Garberson relies on his electric truck, a graphite-gray Rivian, for year-round family road trips to see his parents, who live a few hours away. “My car will drive 200 miles in freezing conditions in the Midwest,” said the head of growth and research at Recurrent, a company that aggregates data on battery health from more than 29,000 EVs across the United States.

Switching from a gas car to an EV is one the biggest actions an individual can take to reduce their emissions. But EVs have gotten something of a bad rep in cold weather. It’s true that they, like gas cars, lose range as temperatures fall: Depending on the EV, the drop can be 16% to 46%. That loss may be anxiety-provoking, especially for EV owners-to-be.

From Garberson’s perspective, the criticisms are overblown. EVs work even in the most bone-chilling climates across the continental U.S., he said. In any case, Recurrent has found that knowledge and experience go a long way toward relieving those fears.

Plenty of frosty regions are embracing electric cars. Just look at Chicago. Despite its freezing winters, it’s one of the top cities for EV registrations, with more than 25,000 in the 12 months ending in June 2024, according to Experian’s most recent available data. Outside the U.S., the trend holds, too: In Norway, where temperatures can drop below -4˚F, nearly 9 out of 10 new cars sold in 2024 were fully electric.

In this article, we’ll dive into how to get the most winter range out of an EV. First up is a key EV feature to look for if you’re still shopping. Then, for those who already have an electric car, Garberson shares his top range-extending strategies.

EV range shrinks in the cold partly because the chemical reaction in their massive lithium-ion batteries slows down. But the biggest reason for winter range decline is the need to keep passengers warm, Garberson said.

Gas cars use the waste heat generated from the internal combustion engine for cabin heating. EVs don’t have an engine (they have a motor), so they don’t produce enough accidental heat to keep occupants cozy in frigid weather. Instead, EVs siphon energy from the battery to heat the cab, leaving less for propulsion. EVs can either make heat with an electric-resistance heater, which is like turning on a toaster, or much more efficiently move heat from the outdoors into the car using a heat pump.

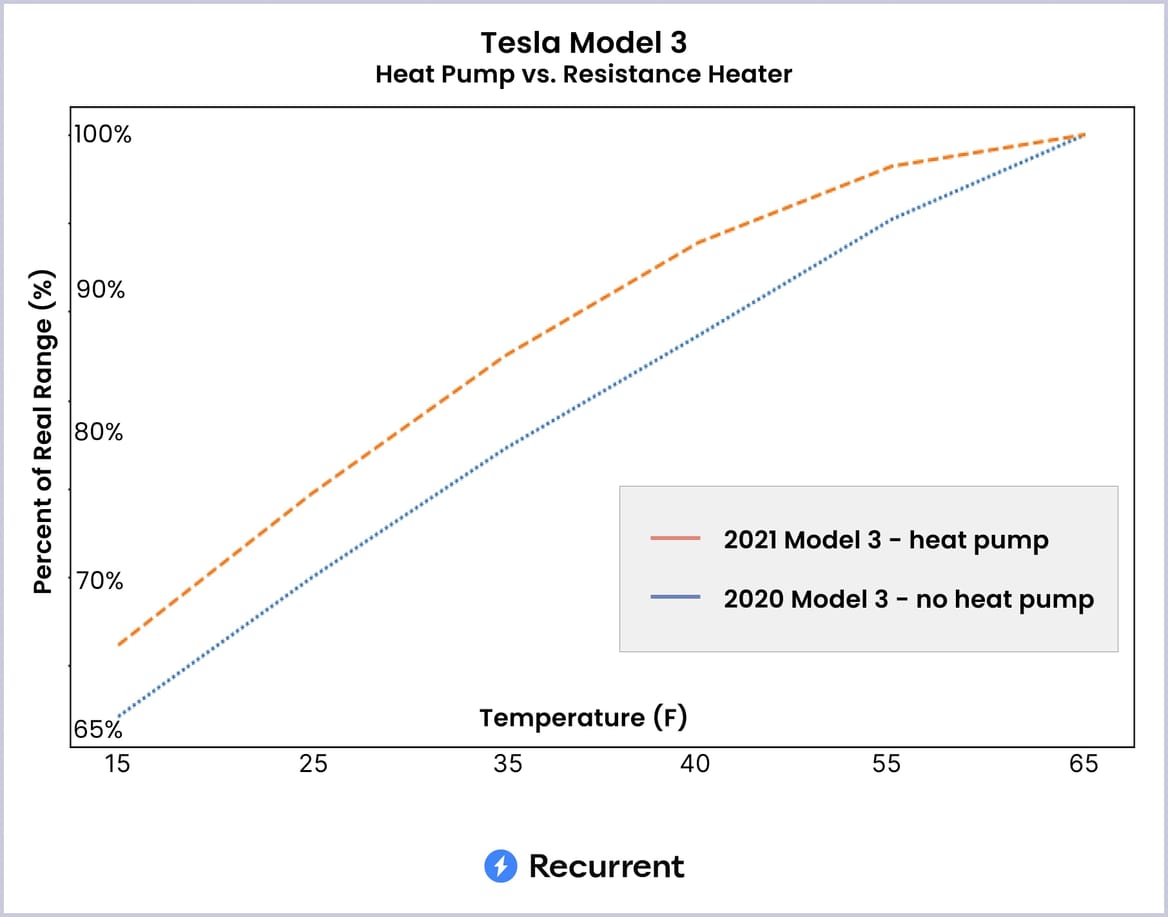

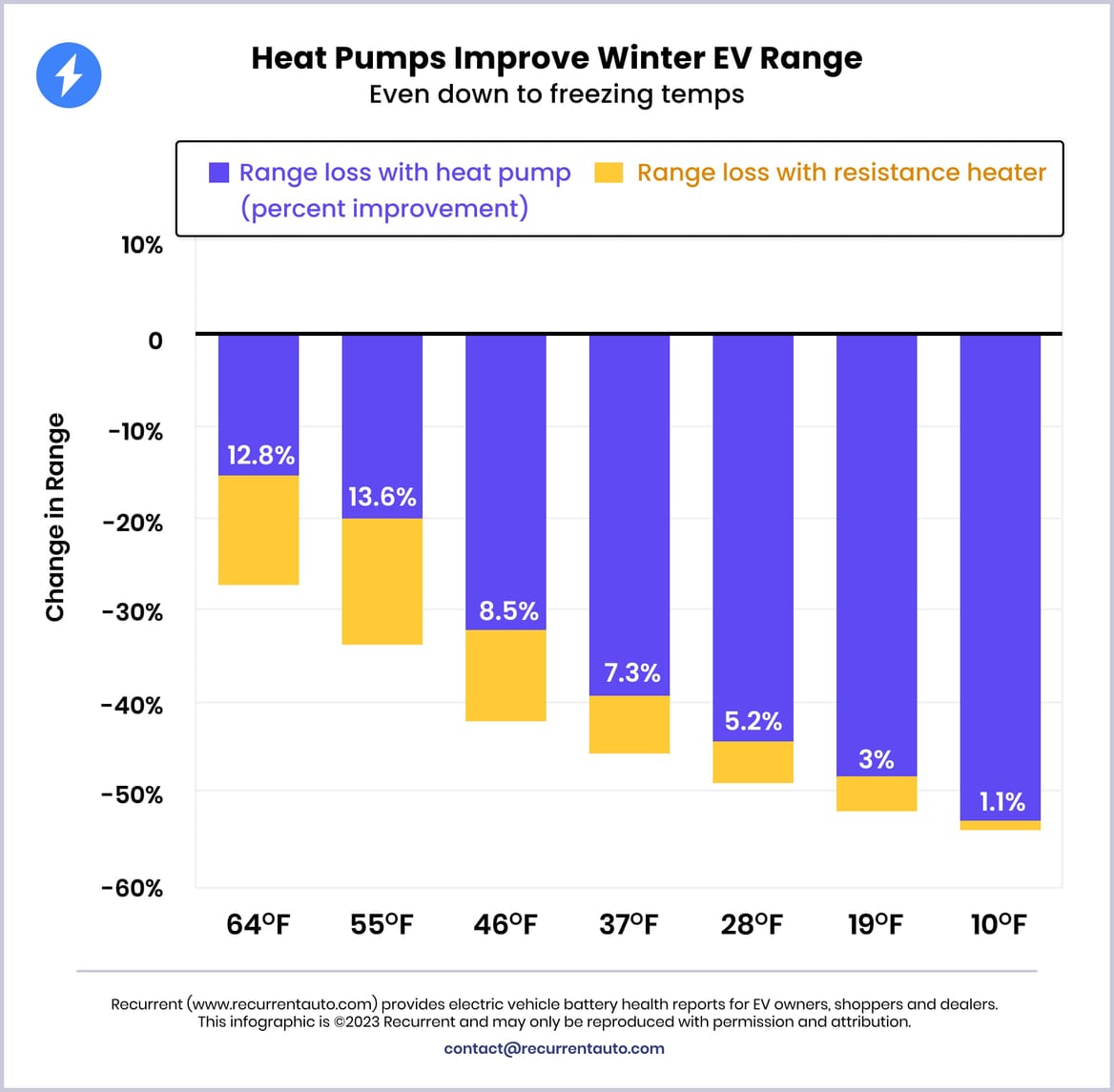

Heat pumps are famous for their critical role in decarbonizing space heating in buildings. They don’t burn fossil fuel, and they’re typically two to three times as efficient as gas and electric-resistance systems, even below freezing. But the tech has also made its way into clothes dryers and water heaters. Now found in some EVs, heat pumps improve range by 8% to 10% in cold conditions, according to Recurrent.

According to Recurrent’s analysis, electric vehicles with the best winter range tend to have heat pumps, including the Tesla Models X, S, 3, and Y; Audi e-tron; and Hyundai Ioniq 5 and Kona.

It’s worth pointing out that heat pumps themselves are less effective as temperatures drop. Even so, EVs with heat pumps offer better range than those with electric-resistance heating. Recurrent points out that at 55˚F, a heat pump reduced range by 20% while a resistance heater lowered it by 33%. As the weather gets colder, the difference in range between EVs with heat pumps and those with resistance heaters shrinks.

To be clear, EVs work well in the winter even without heat pumps, Garberson said. His Rivian truck doesn’t have one, and on a day-to-day basis, he doesn’t even notice the decline in range. He charges at home, which makes topping up easy. For longer road trips, cold weather might mean he needs one more charging stop than he normally would.

Heating technology aside, drivers can take steps to get more out of their EVs in the cold. Recurrent’s Garberson offered his top three range-saving strategies for winter EV drivers.

Prewarm your EV while it’s plugged in. Garberson’s garage isn’t climate-controlled, so his vehicle gets chilly when the weather does. About 10 minutes before he hops in, he uses his car’s app to warm up the cabin. Pulling electricity from the wall outlet means he won’t have to use the battery to bring his car from 4˚F to a toasty 70°F.

Set your charging limit higher. Batteries are happiest when balanced at 50% charge, Garberson said. Because huge charge-level swings are harder on the battery, Recurrent recommends keeping it between 20% and 80% full. But “let’s eliminate anxiety from the discussion and just charge cars a bit more in cold conditions,” he advised. If you normally charge to 70% to keep the battery healthy, as Garberson does, increase it to 80% in the winter.

When you’re headed to a fast charger, set the destination in the car’s GPS, a feature in most modern EVs. Letting the EV know will allow it to start preconditioning the battery so it’s ready to charge when you get there. Otherwise, you may need to wait 15 to 20 minutes at the charger for the battery to warm up sufficiently, Garberson said. “It’s just amazing how [electric] vehicles have been designed over the last few years to help drivers without them even knowing.”

One more tip for your kit? Turning on the heated steering wheel and heated seats “is a far more efficient way” to warm yourself and passengers than heating up the air in the car’s cabin, Garberson said. Once the car is prewarmed and you’re on the road, you could dial down the thermostat and use the targeted heat features to keep you cozy.

But most importantly, Garberson added, do what you need in order to keep yourself and your passengers happy. He’s father to a one-year-old, so “relying on heated seats is not part of my driving equation.”

Besides, “I will admit I am kind of a sucker for creature comforts,” Garberson said. “I need heat any way I can get it.”

Manufacturers provide even more advice on how to extend the winter range of your particular EV model, so be sure to check out their online guides.

A little planning and know-how can go a long way toward a smooth EV experience in frosty weather, Garberson said. Winter takes a bite out of his EV’s range, yes, but “I get by just fine.”

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

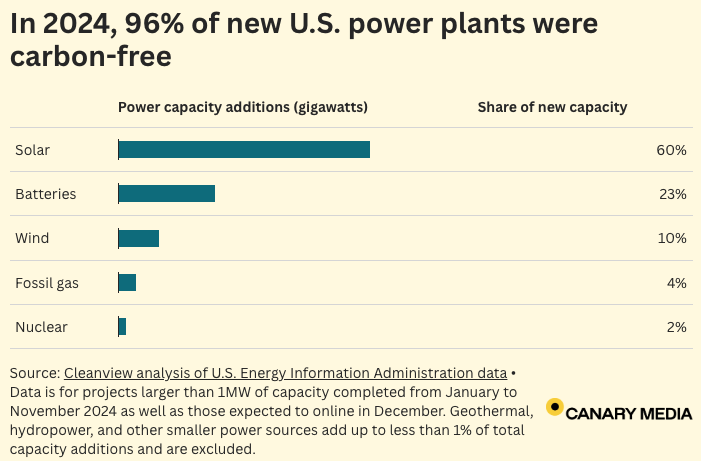

The amount of carbon-free energy built in the U.S. last year far eclipsed the growth of new fossil-fueled power plants.

The U.S. grid added a total of just over 56 gigawatts of power capacity last year. A whopping 96 percent of that came from solar, battery, wind, nuclear, and other carbon-free installations, per new Cleanview analysis of U.S. Energy Information Administration data.

Solar installations dominated power plant additions — 34 gigawatts of utility-scale solar were constructed across the U.S., a 74 percent jump from 2023’s record-high year. Texas and California drove most of this surge.

Grid batteries were the next-biggest new source of power capacity — and saw the fastest growth. The U.S. built 13 GW of energy storage last year, almost double 2023’s record-shattering 6.6 GW. Texas and California led the way here as well.

Wind was the third-biggest source of new capacity, but installations dropped for the fourth year in a row as the industry continued to struggle through lingering supply-chain issues, a plodding interconnection process, and local opposition to projects. Just 2.4 GW of new gas and 1 GW of nuclear went online in 2024.

The U.S. has rolled out more clean energy than fossil-fueled power plants for years now, helping the grid get cleaner and less carbon-intensive. Power emissions have fallen steadily since peaking in 2007 as fossil gas and renewables have replaced coal.

Still, fossil fuels generate the majority of the country’s power and the U.S. faces an uphill battle to decarbonize its grid by 2035, a goal set by outgoing President Joe Biden.

Fossil gas is currently the top source of electricity generation in the U.S., and last year emissions from its use in the rose nearly 4 percent. As big tech firms look to build more energy-intensive data centers to support their AI goals, the sector could become even more reliant on fossil fuels. That surging power demand is already extending the life of coal plants and causing utilities to propose building more gas-fired power plants.

In order to eliminate carbon emissions from the grid, the U.S. is going to need to figure out how to build enough clean energy to dethrone fossil fuels. That was a hard task even when Biden was president and before the AI-driven electricity boom took hold. It will be an even taller task under incoming President Donald Trump, who has vowed to double down on fossil fuels.

The Trump administration has declared that it is rescinding guidance for a $5 billion program that funds EV-charging installations nationwide, potentially halting states’ plans to put billions of obligated but as-yet unspent dollars to work. It’s the new administration’s latest attack on federal climate and clean energy programs authorized by Congress during the Biden administration, and like the others, it’s almost certain to be challenged in court, experts say.

The unexpected news came in a Thursday memo from the Federal Highway Administration to state transportation departments responsible for managing the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Formula Program. NEVI was created by the bipartisan infrastructure law passed by Congress in 2021 to establish reliable charging along major highways across the country. The program is structured to guarantee states access to funds under federally approved plans through fiscal year 2026.

The memo states that FHWA is “immediately suspending the approval” of these state plans pending a U.S. Department of Transportation review. States’ “reimbursement of existing obligations will be allowed in order to not disrupt current financial commitments,” the memo notes. But “no new obligations may occur” until new guidance is developed and states submit and receive approval for their updated plans — a process that could last through the rest of this year.

The memo’s instructions conflict with longstanding practice of guaranteeing states access to federal highway spending as well as with the structure of the NEVI program set by Congress in the infrastructure law.

“Freezing these EV charging funds is yet another one of the Trump administration’s unsound and illegal moves,” Katherine García, Sierra Club’s clean transportation for all director, said in a Friday statement. “This is an attack on bipartisan funding that Congress approved years ago and is driving investment and innovation in every state, with Texas as the largest beneficiary.” The Lone Star State is slated to receive nearly $408 million from the program.

Of the $5 billion authorized by NEVI, $3.27 billion has been obligated to all 50 states, Washington, D.C., and Puerto Rico, according to EV-charging data firm Paren. Of that, roughly $615 million is under contract for constructing almost 1,000 charging sites, Loren McDonald, Paren’s chief analyst, said in a webinar last month.

In a Thursday email, McDonald highlighted that “companies that are under contract with a state and have incurred expenses will get reimbursed.” At the same time, “the experts in Washington, D.C., that we have spoken to in the last few months believe that changes in NEVI like this would require a change in the law from Congress.”

“Our understanding is that FHWA does not have the authority to actually halt or revise the NEVI program this extensively, but will move forward, creating havoc for several months until lawsuits, the courts, and Congress resolve it,” he wrote.

Under the Biden administration, NEVI program formula funding was allocated through fiscal year 2026, and FHWA had approved states’ annual spending plans through fiscal year 2025, Kelsey Blongewicz, policy analyst at research firm Atlas Public Policy, told Canary Media last month.

That funding is “tied to approved state plans and contracts that makes it nearly impossible to reverse or stop,” Beth Hammon, senior EV infrastructure advocate at the Natural Resources Defense Council, wrote in a blog post last month.

Still, FHWA’s new instructions “create great uncertainty for the billions of dollars states and private companies are investing in the urgently needed infrastructure to support America’s highway transportation network,” Ryan Gallentine, managing director at Advanced Energy United, said in a Thursday statement. The trade group represents EV manufacturers, charging infrastructure developers, and other companies involved in NEVI-funded projects.

“States are under no obligation to stop these projects based solely on this announcement,” he wrote. “We call on state DOTs and program administrators to continue executing this program until new guidance is finalized.”

President Donald Trump attacked EVs and the NEVI program on the campaign trail. His administration issued an executive order within hours of his inauguration demanding a halt to all Biden-era climate and clean energy spending and singled out the NEVI program for scrutiny.

Federal agencies have since halted the flow of tens of billions of dollars of federal climate and clean energy funding, drawing outrage from state agencies, nonprofit groups, and companies that have been unable to recover money already spent on projects and programs. Two federal judges have responded to lawsuits challenging the freeze by issuing court orders demanding a halt to them, but a multitude of programs remain inaccessible, according to reports from grant recipients.

Confusion over the NEVI program’s future comes at a moment when significant investments are starting to flow from states to EV-charging manufacturers and charging-network providers — including Tesla — after years of bureaucratic and administrative delays. Federal data as of November tracked 126 operational public charging ports at 31 sites built using NEVI funding.

The Biden administration hoped to spur the buildout of 500,000 public charging stations by 2030, up from about 206,000 today. The NEVI program wasn’t intended to build all those chargers itself but to help install them in places where the economics of providing EV charging aren’t yet supported by the number of EVs on the road, McDonald said.

“In many states, the NEVI program helped jumpstart investment in high-speed EV charging stations, getting high-speed chargers at the gas stations and truck stops where millions of drivers already stop every year,” Ryan McKinnon, spokesperson for Charge Ahead Partnership, a trade group representing fueling-station owners and convenience store chains that make up the majority of NEVI charging sites, said in a Friday statement. “Other states dragged their feet.”

According to McDonald, since NEVI was singled out by the Trump administration, six states have indefinitely discontinued work on it, including Ohio, the Republican-led state that installed the program’s first live chargers in 2023.

UPDATE: In a Friday email, an FHWA spokesperson stated the agency is “utilizing the unique authority afforded under the NEVI Formula Program to ensure the Program operates efficiently and effectively and aligns with current U.S. DOT policies and priorities.”

Massachusetts’ attorney general says plans by the state’s major utilities to lower the cost of charging electric vehicles would offer little actual savings for customers.

In response to a 2022 Massachusetts climate law, the state’s two primary electric utilities, Eversource and National Grid, have proposed plans to create lower rates for charging EVs during off-peak hours, which they say would be implemented no sooner than 2029.

In a regulatory filing last week, however, the state’s attorney general said the utilities’ estimated savings for customers are based on faulty calculations and would be much lower in reality. Plus, a requirement that households and small businesses pay for additional meters to track their charging stations’ power use “negates all financial value for the customer.”

With this filing, the attorney general’s office joins climate advocates who support the idea of offering EV drivers the chance to save money by charging during off-peak hours but take issue with the way utilities propose to implement the strategy.

“If you require that people install a second meter and that they cover the cost of that installation, nobody’s going to do it,” said Anna Vanderspek, electric vehicle program director at the Green Energy Consumers Alliance.

Regulators have asked the utilities for feedback on the attorney general’s concerns and recommendations by February 20. A spokesperson for Eversource did not specifically address the attorney general’s criticism when asked about it but said the utility believes in the benefits of time-of-use pricing and looks forward to continuing the regulatory process. National Grid did not respond to a request for comment in time for publication.

More than a third of cars sold in the United States are likely to be EVs by 2030, J.D. Power forecasts, a prospect that has many industry and elected leaders wondering whether the country’s electric infrastructure is ready to provide power for this growing, gas-free fleet.

Massachusetts has set the ambitious target of putting 900,000 EVs on the road — and on the grid — by 2030. So, like other states facing the same challenges, Massachusetts has turned to the idea of using financial incentives to encourage EV owners to charge during off-peak hours and to lower the cost of charging for drivers in a state where electricity prices are among the highest in the country.

“Electric vehicle time-of-use rates could be a very valuable tool for helping to alleviate the load on the system as well as helping to incentivize people to think about when they’re using electricity,” said Priya Gandbhir, director of clean power at the Conservation Law Foundation.

In the 2022 climate law, legislators required utilities to propose these so-called time-of-use rates, which both Eversource and National Grid did in August 2023.

Eversource’s plan calls for a $15 monthly fee and an off-peak EV charging rate of 19 cents per kilowatt-hour, slightly more than half the proposed peak rate. National Grid would impose a $10 monthly fee and charge 14 cents per kilowatt-hour for off-peak charging, half what the peak rate would be. Both plans would require a separate meter, and both contend the rates cannot be implemented before advanced metering infrastructure is rolled out and tested, a process they expect to take at least four years.

Regulators must rule on these proposals by the end of October.

The numbers laid out by the utilities don’t add up to savings for consumers, the attorney general’s testimony argues. Thus, the proposals are unlikely to motivate more people to buy EVs or to shift their charging times.

The utilities did not estimate the cost of installing a separate meter, but online estimates run from $1,400 to more than $4,000. At the same time, the utilities drastically overstated the savings their plans would yield by using inflated estimates for how many kilowatt-hours the average driver would use to charge their EV, the attorney general’s testimony says. Rather than saving as much as $146 a month, as the utilities calculated, drivers would cut their bill by $21 per month at most, assuming they do all of their charging during off-peak hours. Customers who sometimes charge during peak hours could even see bill increases.

“The math just doesn’t work out,” Vanderspek said.

The attorney general’s office recommends that public utilities regulators reject National Grid and Eversource’s proposals and offers several alternative approaches. The simplest, the testimony says, would be to offer whole-home time-of-use rates, rather than separating out the vehicle charging load. Evidence from other states suggests such a rate could be implemented during the roll-out of advanced metering infrastructure, rather than waiting the minimum of four years the utilities say would be necessary for an EV-specific rate. The filing points to Colorado, where time-of-use rates are rolling out in concert with advanced metering infrastructure.

Another option would be to use data collected by vehicle computer systems or chargers themselves to issue rebates or apply lower rates for charging done at off-peak times. Utilities in California and Minnesota have already deployed this approach.

The same data could be used to offer other financial incentives. National Grid, in fact, already offers such a program in Massachusetts, giving customers 5 cents per kilowatt-hour for off-peak EV charging during the summer and 3 cents per kilowatt-hour the rest of the year.

Any of these approaches could be used not just to improve financial incentives for customers but also to speed up their implementation, to the benefit of both consumers and the environment, Vanderspek said.

“We’re all better off if we’re shifting that load off-peak right now,” she said.

Canary Media’s chart of the week translates crucial data about the clean energy transition into a visual format.

Nearly $2.1 trillion was invested in the global energy transition in 2024 — the highest-ever annual amount.

Last year’s total energy-transition investment was 11% higher than in 2023 and more than double what was spent in 2020, per BloombergNEF.

Most of this money is flowing to two energy-transition sectors: electrified transportation and clean energy.

More than $757 billion was invested in passenger and commercial EVs, electric two- and three-wheelers, and public EV-charging stations. That’s a 20% increase from 2023. Another $728 billion was spent on renewable energy projects ranging from wind to solar to hydropower, a record high but only about 8% more than in 2023. Energy-storage spending, meanwhile, surged 36% last year to nearly $54 billion.

The third-biggest category was power grids, which need to grow in every country to accommodate the rapid expansion of clean energy. Just over $390 billion was invested in 2024 on expanding and retooling grids across the world, up about 15% compared with the year prior.

While funding for these mature energy-transition technologies reached new heights in 2024, earlier-stage climate technologies had a rougher year. Spending on carbon capture and storage was less than half of what it was in 2023. Investment in hydrogen and clean-industry projects was also cut almost in half.

China alone accounted for nearly 40% of last year’s energy-transition investment, outpacing the U.S., EU, and U.K. combined. China also grew its spending faster than any other major country or region last year, while in the EU and the U.K., the sector attracted less money than in the prior year.

By a different measure, from the International Energy Agency, energy-transition investment is now far exceeding funding for fossil-fuel projects. That’s a good thing for the global bid to eliminate use of planet-warming fossil fuels. But even last year’s record-setting pace is not enough to decarbonize the planet. More is needed, the IEA says, especially in developing nations.

The U.S. solar energy industry has succeeded in doing something that would have been hard to imagine a few years ago: It has officially built more than enough factories to meet the country’s demand for solar panels.

The nation can now produce nearly 52 gigawatts of solar panels each year, per a new tally from the Solar Energy Industries Association. That’s up from the 40 GW of capacity reported in late 2024. These numbers don’t count actual production, which is subject to factors like staffing and market demand, but rather what the industry is capable of. Current capacity exceeds the module component of SEIA’s goal from 2020, which was for the whole solar supply chain to hit 50 GW by 2030.

The factory buildout employs workers across the U.S. in high-tech manufacturing roles and diminishes reliance on China, the long-time leader in solar manufacturing. But solar panels, which industry insiders refer to as modules, are just the last step of the solar supply chain: Currently, U.S. factories assemble modules from solar cells that are almost exclusively produced overseas. Those cells, which convert sunlight into electricity, incorporate wafers that are meticulously sliced from silicon ingots; factories that make ingots, wafers, or cells are more complex and capital-intensive than module assembly plants.

Those precursor steps have lagged behind the U.S. module buildout, but companies have pledged to build factories for 56 GW of solar-cell capacity in the next few years, SEIA said. Those proposed projects, if they get built, would meet the needs of the newly revitalized U.S. solar-panel industry. But erecting solar-cell factories requires a step change in capital investment compared with module assembly.

In November, legacy solar manufacturer Suniva kicked off the first new domestic cell production since U.S. producers (Suniva included) succumbed to competition from China in the 2010s. ES Foundry launched pilot cell production at its South Carolina plant in January. The company plans to employ around 500 workers by this summer and ramp up to 3 GW of annual production capacity by the end of September.

Five more cell factories are under construction, per SEIA. They include QCells’ complex in north Georgia, which should bring 3.3 GW of cell production online later this year, and Silfab Solar’s 1 GW plant in South Carolina.

But President Donald Trump swiftly attacked his predecessor’s investments in clean energy, signing an order on his first day in office to “immediately pause the disbursement of funds” from the Biden administration’s landmark climate and infrastructure laws. That order targets grants, loans, and other appropriated funds and therefore does not seem to affect tax credits, Canary Media previously reported. But the move has sown confusion in clean-energy markets and could presage attempts to undo the legislation that created the tax credits.

Some companies are thus holding back on solar-cell factory investments until they see what the Trump administration does with a key manufacturing tax credit, which has proven vital to secure construction loans.

The rebirth of U.S. solar manufacturing had to start somewhere, and assembling panels made sense as that first step. Now, all those panel makers could become anchor customers for the next link in the chain — the proposed cell manufacturers. But making that jump isn’t so easy.

Take the case of Heliene, a company based in Ontario, Canada, that nonetheless has established its bona fides as a committed U.S. solar manufacturer.

Heliene opened a solar-module factory in Mountain Iron, Minnesota, back in 2017, during the first Trump administration. The company later expanded that facility to assemble 800 megawatts of panels per year with a staff of 320 workers. Another expansion is already underway to grow that workforce to 520 and capacity to 1.3 GW by April.

In November, when previously bankrupt Suniva began the first U.S. cell production in years, Heliene swooped in to purchase every cell Suniva’s new factory could make. Heliene could, for the time being, tout its products as the only U.S.-built modules filled with U.S.-built cells.

Now Heliene is working on its boldest move yet: a $200 million solar-cell factory to be built somewhere in the U.S. in partnership with India’s Premier Energies. But Heliene founder and CEO Martin Pochtaruk told Canary Media in January that he couldn’t make the final call on that plant given the uncertainty around what will happen to Biden-era tax credits under Trump.

Building a cell factory requires a significant step up in dollars and complexity compared with a module-assembly plant, Pochtaruk explained. Putting panels together is a largely mechanical task that costs around $30 million of capital investment for every GW of production, he said.

Solar-cell production costs more than four times that, at about $130 million per GW, Pochtaruk noted. “It’s a chemical process that is much more complex. You need to build a clean room that is similar to an operating room, but industrial-sized.”

Cell production exposes silicon wafers to chemicals in liquid and gaseous forms, which must unfold in precisely calibrated environments, Pachtaruk added. Water used in the process requires treatment before it can be reused or sent to the sewer. The equipment to do all these things drives up costs relative to module assembly and makes permitting more complicated.

That raises the stakes for anyone looking to put their chips on the table for American solar-cell production — even if they’ve already found success in their panel-assembly bets. The prospects of financing these bigger bets are intimately tied to the future of federal manufacturing tax credits, part of the Biden policies that Trump has vowed to dismantle.

Even successful solar manufacturers typically don’t want to fork over their own cash for the hefty expense of a new cell factory. They turn to lenders to finance construction costs. But lenders have a hard time loaning money to a type of business without much of a track record to evaluate, and the current U.S. cell-manufacturing landscape is mostly nonexistent.

Cell manufacturers have something else going for them, though: the 45X tax credit. As enacted in the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, 45X awards a set amount of money for each key solar component that a company makes in the country in a given year. If the manufacturer doesn’t have enough tax liability to absorb all that credit, it can sell the credits to another entity, generating cash to pay down debt or invest in further expansion.

Heliene pulled that off last fall with 45X credits from module production and netted about $50 million from the transaction.

Financial institutions mulling a $100 million–plus loan to a solar-cell manufacturer want to use the future 45X credit as collateral, Pochtaruk said. Future cell sales may be hard to predict, but a guaranteed payout based on the number of cells produced is easy to model (at least in a world where the U.S. government honors legally binding contracts and pays its obligations).

“Lenders will not agree to come forward until there’s clarity” on the long-term status of the tax credits, Pochtaruk said. So Heliene is still finalizing a location in the U.S., tabulating construction costs, and then will need to make a final call on the investment by late April. A Premier Energies executive told investors Monday that the plan is on pause pending clarity on the fate of the tax credits.

The potential loss of tax credits may be less consequential to companies like Qcells, which can draw construction funds from its corporate parent, Korea’s Hanwha. A smaller solar-focused company like Heliene doesn’t have other corporate coffers to rely on in lieu of tax-credit–based financing.

It’s still entirely possible that the credits will survive. Under normal circumstances, it would take a new act of Congress to undo them. A cadre of Republicans in Congress has publicly urged leadership to preserve them, based on the economic benefits they bring to their districts. Meanwhile, SEIA coordinated a lobbying push on Capitol Hill Wednesday to meet with more than 100 members of Congress or staff to urge them to protect the credits.

The current uncertainty, though, is at the very least delaying the commitment of more private funds to build solar-cell factories. Those projects — and the high-tech, well-paying manufacturing jobs they come with — could collapse altogether if the situation persists or Congress undoes the recently created tax credits.

Since launching in 2019, the U.S. startup Brimstone has positioned itself as a pioneering producer of low-carbon cement. The company’s technology can make the essential material without using any limestone — the carbon-rich rock that, when heated up in fiery kilns, releases huge amounts of planet-warming gases into the air.

Now, Brimstone is looking to use its same process to supply another emissions-intensive industry: aluminum production.

The Oakland, California-based company sources carbon-free rocks that are widely available in the United States but are primarily used today as aggregate for building and road construction. Brimstone pulverizes those rocks and adds chemical agents to leach out valuable minerals. Certain compounds are then heated in a rotary kiln to make industry-standard cement.

Last month, Brimstone announced that its novel approach can also yield alumina, which is the main component of aluminum — the lightweight metal found in everything from household appliances and smartphones to buildings, bridges, and airplanes. Aluminum is also a key ingredient in many clean energy technologies, such as solar panels, heat pumps, power cables, and electric vehicles.

Alumina production today involves extracting and refining a reddish clay ore called bauxite from a handful of countries using environmentally destructive methods. The United States imports nearly all of the alumina it needs to feed its giant, energy-hungry smelters. Over half that supply comes from Brazil, with Australia, Jamaica, and Canada providing most of the rest.

Brimstone says its approach could reduce or supplant the need to scrape bauxite from overseas mines, a process that generates copious amounts of toxic waste. Instead, the company aims to supply U.S. aluminum smelters by sourcing common calcium silicate rocks from domestic quarries and by using chemicals that can be more efficiently recycled than bauxite.

The strategy might also help the six-year-old startup navigate the fraught early period that many newcomers face when trying to break into giant, incumbent industries. Cement is a fairly cheap and abundant material, and the construction sector is inherently wary of deviating from tried-and-true — if carbon-intensive — practices. But the U.S. makes relatively little smelter-grade alumina, despite the essential role it plays in the country’s economy.

“Alumina is a very high-value product that allows us to get into the market…and be very investable in the beginning,” Cody Finke, Brimstone’s co-founder and CEO, told Canary Media. He said that producing alumina could help his team “bridge that valley of death” as it works to scale low-carbon production of cement, which he described as a “larger but lower economic driving force” for the business.

The company, which has raised more than $60 million in venture funding, is slated to open a pilot plant in Oakland later this year that will produce alumina alongside Portland cement — the product that comprises the vast majority of cement made today — and supplementary cementitious materials. Brimstone also plans to build a $378 million commercial demonstration plant by the end of the decade, the site for which is still being decided.

Brimstone is expanding its scope during an especially dynamic period for the aluminum sector.

In recent decades, U.S. aluminum producers have significantly reduced domestic production in response to spiking energy prices and increased competition from China. That in turn has reduced alumina demand from U.S. smelters — which dissolve the alumina in a molten salt called cryolite, then heat and melt it to make aluminum metal. From 2019 to 2023, U.S. alumina imports fell by nearly 33% as manufacturers closed or curtailed their operations.

President Donald Trump has called for imposing fresh tariffs on U.S. aluminum, copper, and steel imports as a way to “bring production back to our country,” and his administration this week imposed or threatened duties on imports from Canada, Mexico, and China, a sweeping action that affects aluminum products. Industry analysts told Reuters that aluminum tariffs would result in higher costs for U.S. consumers, at least until domestic output ramps back up. The country-focused tariffs have already sparked volatility across commodities markets.

At the same time, however, Trump is trying to block federal investments that could boost domestic production of both aluminum and alumina.

Century Aluminum, for example, is set to receive up to $500 million from the U.S. Department of Energy to build the nation’s first new smelter in 45 years. The Biden administration finalized the award on January 15 as part of its larger initiative to slash emissions from industrial manufacturing. Century’s “green smelter” — the location of which hasn’t been announced — will purportedly emit 75% less carbon dioxide than traditional smelters, thanks to its use of carbon-free energy and energy-efficient designs.

The DOE award is currently entangled in Trump’s freeze on tens of billions of dollars in congressionally mandated climate and energy spending. Brimstone is also affected by the pause. In December, the DOE awarded Brimstone up to $189 million to cover half the cost of its planned commercial demonstration plant.

Brimstone declined to comment on the federal funding fracas, which remains in flux even though federal courts have ordered the flow of investment to resume.

Despite the policy uncertainty, there are still potential upsides to making alumina from alternatives to bauxite and within the United States.

Producing alumina using less environmentally intensive techniques — and supplying that material to smelters powered by clean energy — would help lower emissions across the U.S. supply chain and provide much-needed metal for domestic manufacturers. Lessening the country’s reliance on imports could also help insulate the United States from supply chain disruptions and national security risks, according to a 2018 report by the U.S. Department of Commerce.

“Aluminum is a linchpin of domestic aerospace, defense, and automotive applications,” Kevin Kramer, a former executive for U.S. aluminum maker Alcoa who is now a Brimstone senior advisor, said in a statement. “Establishing a new alumina source stateside is vital, and Brimstone’s 100% U.S.-based solution is exactly what the industry needs.”

Three U.S. states — Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia — mine small amounts of bauxite for chemical and industrial applications. The nation’s single alumina refinery, located in Louisiana, uses imported bauxite to make alumina for aluminum smelting. But most of the world’s alumina production happens in other countries with much larger bauxite deposits.

Other types of minerals and clays also contain alumina, though the modern industry only deals with bauxite. That’s because of “the relatively straightforward nature of extracting bauxite, combined with its commercial abundance,” Adam Merrill, a mineral commodity specialist at the U.S. Geological Survey, said by email. Nearly all commercially produced alumina uses the Bayer process, which involves dissolving bauxite in a high-temperature caustic solution and filtering it to remove impurities.

“Today, the process is used much in the same way as when it was patented in 1888,” he added.

Merrill said that, aside from Brimstone, he isn’t aware of other current research efforts that involve using calcium silicate rocks for alumina production. Earlier studies in the mid-20th century pointed to the fact that silicates contain relatively tiny quantities of alumina — meaning producers would have to dig up substantially more rocks to match what they’d get from bauxite.

Finke said that Brimstone’s answer to this challenge is “co-production,” something he said the industry hasn’t tried before in a meaningful way.

“We’re not just taking the bit of alumina that’s in this and then throwing the rest out,” he said, holding up a small chunk of the silicate rock basalt. “We’re additionally making Portland cement and supplementary cementitious materials. That’s really what our insight was.”

Brimstone plans to mine rocks from existing surface quarries across the United States. At its future commercial demonstration plant, about 20% of its total product will be smelter-grade alumina, with the remaining materials turned into inputs for concrete.

“This would be the first time that alumina is produced from a rock quarry in the United States in a generation,” Finke said of the facility.

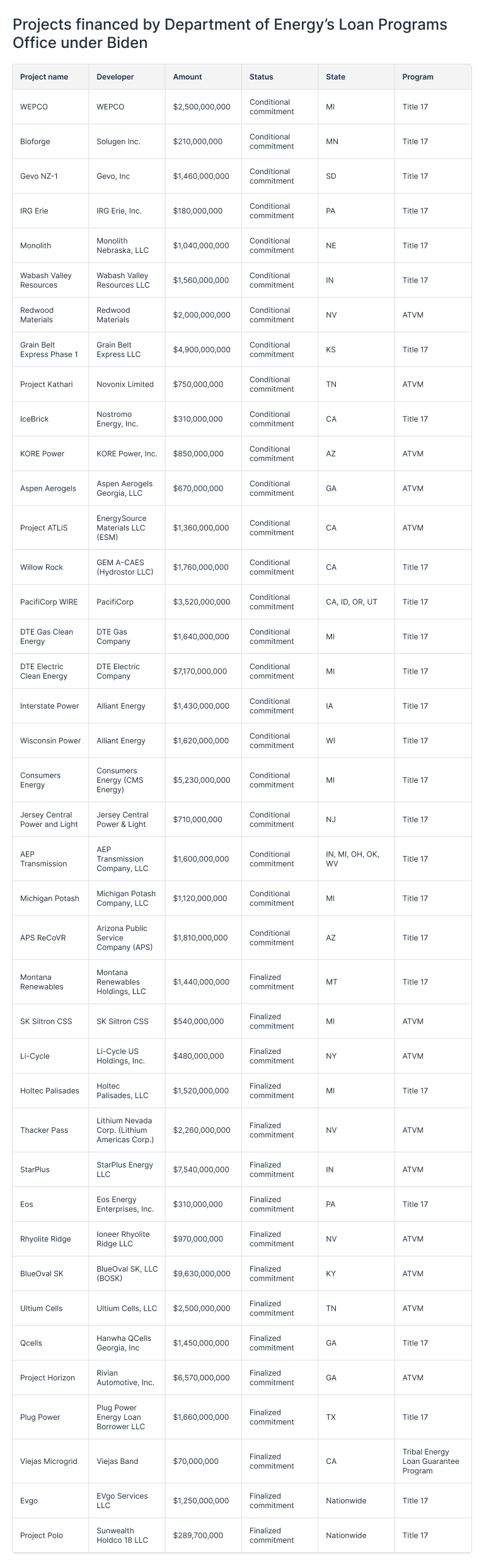

The Department of Energy made an unprecedented number of loans to ambitious clean energy projects throughout the Biden administration. Now the fate of that financing is uncertain amid President Trump’s ongoing attacks on federal climate and clean energy spending.

Under Biden, the DOE’s Loan Programs Office issued a total of 53 loans and loan guarantees worth over $107 billion. They went to large-scale projects including electric-vehicle factories from Ford and Rivian, the restart of the Palisades nuclear power plant in Michigan, and facilities that produce sustainable aviation fuel. The map below, based on public DOE data compiled on January 17 and shared with Canary Media, shows LPO loans by status for projects where geographic data is available. See the data table at the end of this article for more information on all projects that received LPO loans.

It’s unclear how the Trump administration will treat these loans.

LPO’s new director, John Sneed, is exploring whether it’s legally viable to cancel existing loans made by the office, per reporting from Bloomberg.

About 44% of the LPO financing announced under Biden — nearly $47 billion — is currently in the conditional phase, meaning it’s unfinalized and still subject to negotiations with the federal government. A big question mark hangs over these conditional loan commitments, though even finalized loans could be targeted for clawbacks, experts say.

The LPO, which awarded key financing to Elon Musk’s Tesla in 2010, saw its lending authority soar to nearly $400 billion thanks to the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act. As of January 17, the office reported that over 160 applicants were currently seeking more than $200 billion in loans for various energy projects.

Sneed intends to focus the office’s remaining loan authority on technologies like nuclear power and liquefied natural gas, Bloomberg reported, technologies favored by Trump’s newly confirmed Energy Secretary Chris Wright. Wright is the founder and former CEO of fracking firm Liberty Energy and sat on the board of small modular nuclear startup Oklo. Liberty also invested $10 million in next-gen geothermal startup Fervo Energy under Wright’s tenure.

The LPO’s stated mission is to provide low-cost financing to clean energy and transportation projects that struggle to attract investment from traditional lenders who are wary of unique or first-of-a-kind investments. In seeking to make good on that promise, the LPO has actually earned — not lost — money over its 20-year history.

See the table below for the full list of Biden-era LPO loans.

As temperatures dipped well below freezing last month in Asheville, North Carolina, the heat pumps at Sophie Mullinax’s house hummed along, keeping up just fine.

The fact she was warm inside without a gas furnace while the outdoor temperature read 9 degrees Fahrenheit reaffirmed a core belief: “Electrification is better in almost every way you slice it.”

Mullinax is chief operating officer for Solar CrowdSource, a platform that connects groups of customers with solar panels and electric appliances. Since last spring, the company has been preparing for North Carolina’s first-ever statewide incentives for switching out gas stoves and heaters for high-efficiency electric versions.

The Energy Saver North Carolina program, launched in mid-January, includes more than $208 million dollars in federally funded rebates to help low- and moderate-income homeowners make energy-saving improvements, including converting to electric appliances.

“The electric counterpart to every single fossil-fuel technology out there does the same job better,” Mullinax said, and “has a lower impact on the climate, is healthier, and often saves money.”

Solar CrowdSource, which has partnered with the city of Asheville and Buncombe County to help meet the community’s climate goals through electrification, expects the rebate program to make its task easier.

Still, questions remain about the federally funded inducements, including — perhaps most urgently — whether they can survive President Donald Trump’s unilateral assault on clean energy.

The state’s new incentive program stems from the Inflation Reduction Act, the 2022 federal climate law that unleashed nearly $400 billion in federal spending on clean energy and efficiency — and which is now embattled by a flurry of Trump edicts.

While much of the climate law directs incentives to large, utility-scale wind and solar projects, the $8.8 billion home rebate program is designed to curb planet-warming emissions house-by-house, where there is vast potential for improving efficiency and shifting to electric appliances.

Studies estimate that roughly 35% of home energy use is wasted — lost to inefficient heating and cooling systems and appliances, air leaks around windows and doors, and poorly insulated walls. That’s especially true in states like North Carolina, where building energy conservation codes are woefully outdated.

While homes in North Carolina rely less on fossil-fuel appliances than in other parts of the country, they still contribute to climate change. About a third are heated with fuels other than electricity, per the U.S. Census Bureau. According to the Energy Information Administration, some 15% use gas for cooking. In all, state officials estimate that households that burn gas, propane, and other fuels account for 5% of the state’s net greenhouse gas pollution.

Both energy waste and the rising cost of fossil fuels — whether burned directly in the home or in Duke Energy power plants — contribute to the state’s energy burden. Some 1.4 million North Carolinians pay a disproportionately high fraction of their income on energy bills, according to the state’s latest Clean Energy Plan.

But though the state has long deployed federal weatherization assistance to its lowest-income households, there’s little precedent here for a widespread nudge to electrification, either through carrots or sticks.

Unlike dozens of municipalities around the country, no local government in North Carolina has moved to limit residential hookups for gas; most legal analysts say they lack the power to do so. In 2023, the state legislature made doubly sure of that with a law banning local bans on new gas appliances or connections.

Meanwhile, a decades-old state rule barring ratepayer-funded utility promotions that could influence fuel choice has prevented Duke from offering much in the way of carrots. While shareholders could pay for rebates, they have little motive to do so: Duke acquired Piedmont Natural Gas, the state’s predominant gas utility, in 2016.

For years, Duke has offered incentives, carefully calibrated not to run afoul of state rules, for builders to construct more efficient homes. The latest iteration of those ratepayer-backed inducements is under $2,000 per home. By contrast, the new statewide rebates for upgrading to electric appliances cap out at $14,000 apiece.

“This is the largest and the first program in the state that is truly incentivizing fuel switching,” said Ethan Blumenthal, regulatory counsel at the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association.

A second program within Energy Saver North Carolina offers rebates of up to $16,000 to homeowners who add insulation, plug air leaks, and make other improvements, so long as an audit shows the measures will reduce energy use by at least 20%.

In both cases, North Carolina officials are aiming the incentives at low- and moderate-income households. Those earning less than 80% of the area’s median income — about $70,000, depending on the county — get projects for free, and those earning up to 150% of the median get a 50% rebate.

“That was a choice. The federal government did not require it to be a specifically low- to moderate-income program,” said Claire Williamson, energy policy advocate at the North Carolina Justice Center. Yet, she added, the administrations of former Gov. Roy Cooper and current Gov. Josh Stein have “made sure that these funds are going to people who need them the most.”

Like Solar CrowdSource, the North Carolina League of Conservation Voters has awaited the new rebates for months. Meech Carter, clean energy campaigns director at the group, has been handing out flyers, holding information sessions with legislators and community leaders, and setting up an online clearinghouse for homeowners to explore available incentives.

“Every time I present on the website and what resources are out there, I get so many questions on the rebate program,” Carter said, “especially for replacing gas appliances, propane heaters, and transitioning folks to cleaner sources and more energy-efficient sources.”

Costs and climate concerns are factors, she said, but so is health. Just like fossil-fuel–burning power plants and cars, gas stoves and furnaces emit soot and smog-forming particles. A growing body of evidence shows that these pollutants get trapped indoors and far exceed levels deemed safe.

Now that the rebate program has launched, Carter has dozens of people statewide to call back and assist, including 25 in Edgecombe County’s Princeville, the oldest town in the country chartered by Black Americans.

Edgecombe is among the state’s most impoverished counties, making it a prime candidate for the new rebates. “Considering North Carolina’s energy landscape,” Carter said, “we are very optimistic about this program.”

Yet even champions for the program acknowledge they have questions about its deployment. Despite the immense need, it’s hard enough to expend weatherization assistance money due to distrust in government programs, a dearth of qualified contractors, and other hurdles. Those funds, intended for the state’s lowest-income households, total roughly $38 million per year at the moment, after a big infusion from Congress, according to state officials. The new rebates, if evenly distributed over five years, would more than double that with another $41.6 million annually.

“This is larger than the weatherization assistance program,” said Williamson. “There are many contractors out there, but I think there is going to be a big lift to get people trained.”

Announcing the program last month, Gov. Stein stressed that new contractors and other workers would follow.

“[The Department of Environmental Quality] estimates that the program will support over 2,000 jobs across our state,” Stein said at the launch event. “I’m also eager to see the workforce development opportunities that will come.”

Asked how historically disadvantaged communities could benefit from such opportunities, department spokesperson Sascha Medina said over email, “We have planned this program to launch and ramp up for continuous improvement. We will be focusing our marketing to contractors in high energy burden and storm impacted areas first and will expand from there.”

Still, the counties most devastated by Hurricane Helene, like Buncombe, aren’t first on the program’s outreach list. The department’s analysis of statewide energy burdens led it to choose Halifax County in the eastern part of the state along with Cleveland County, in the foothills.

“The hurricane affected areas add a layer of complexity to the program because the rebate programs cannot duplicate money that has been awarded to households through other recovery funding sources,” Medina said. “As we roll out the program, we will continue to work with our partners in the affected areas and receive guidance from the U.S. Department of Energy.”

That guidance from a Trump-led Department of Energy could imperil the success of the rebates more than any other factor. While the president rescinded his widely panned memo halting virtually all federal government spending, his first-week orders targeting Biden-era clean-energy spending appear to remain in force.

The fact that the federal government signed contracts with the state in accordance with a law passed by Congress should shield North Carolina’s Energy Saver rebate program from harm, Department of Environmental Quality Secretary Reid Wilson said at the launch.

“This is finalized. This is done,” Wilson said.