NUCLEAR: Federal officials finalize a $1.52 billion loan to restart a southwestern Michigan nuclear plant, which has now secured $3.1 billion in subsidies to be the first shuttered U.S. nuclear plant to restart. (Bridge)

ALSO: The AI boom has left big tech companies scrambling to find large amounts of low-carbon energy to power data centers, creating new demand for nuclear power. (Mother Jones)

GRID:

WIND: Wind turbine service technician is projected to be the fastest growing occupation in South Dakota through 2032, according to state labor officials. (South Dakota Searchlight)

SOLAR:

OIL & GAS: North Dakota regulators approve plans for a $3.2 billion plant that would convert natural gas into diesel fuel and lubricants. (North Dakota Monitor)

CLIMATE:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: Ford will start offering customers who buy or lease an electric vehicle a free home charger and installation in an effort to relieve range anxiety. (Detroit Free Press)

NUCLEAR: The Energy Department approves a $1.52 billion loan guarantee to restart the closed Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan, part of a resurgence of interest in nuclear power in the U.S. (New York Times)

ALSO: The AI boom has left big tech companies scrambling to find large amounts of low-carbon energy to power data centers, creating new demand for nuclear power. (Mother Jones)

NATURAL GAS:

CLIMATE: Environmental advocates are skeptical of a federal effort to establish guidelines for voluntary carbon markets. (Grist)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

ELECTRIFICATION:

WIND:

GEOTHERMAL: The U.S. House last week passed a bipartisan bill that aims to speed up approval for geothermal projects. (Think Geothermal)

POLITICS: Climate change is rarely acknowledged by either candidates in a hotly contested U.S. Senate race in Ohio, where some communities are experiencing new clean energy investments under the Inflation Reduction Act. (Inside Climate News)

COMMENTARY: A columnist describes a “tragedy of errors” that has led to the U.S. falling behind China in the race to lead on solar technology. (Bloomberg)

GAS: California Gov. Gavin Newsom vetoed a bill Friday night that would have required public health warning labels on gas-burning ranges and cooktops, saying the measure was “highly prescriptive” and would be difficult to amend in the future as scientific knowledge evolves. (Washington Post)

ALSO: After a federal court struck down Berkeley’s ban on new natural gas hookups, a growing number of California cities are pushing forward with efficiency-based building codes to continue the push toward building electrification. (Inside Climate News)

WIND:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

SOLAR:

UTILITIES: PG&E warned more than 12,000 customers in northern California that preemptive shutoffs are likely this week as high temperatures and gusty winds elevate wildfire risks. (SF Gate)

CLIMATE: As erosion and melting permafrost destroys an Alaska Native village, its residents prepare to complete one of the first large-scale relocations because of climate change. (Associated Press)

OIL & GAS:

POLITICS: Early plans suggest Donald Trump would radically remake the Interior Department, weakening environmental protections and expanding mining and oil and gas development across the West, including on currently protected public lands. (The Guardian/Type Investigations)

COMMENTARY: A wildlife conservationist writes that the Bureau of Land Management’s current Western Solar Plan lacks balance and would put Nevada landscapes at risk. (Nevada Independent)

Residents with heat pumps in four Massachusetts towns will soon pay hundreds of dollars less for their electricity over the winter, thanks to a new pricing approach advocates hope will become a model for utilities across the state.

State regulators in June approved a plan by utility Unitil to lower the distribution portion of the electric rate from November to April for customers who use heat pumps, the first time this pricing structure will be used in the state. It’s a shift the company hopes will make it more financially feasible for residents of its service area to choose the higher-efficiency, lower-emissions heat source.

“We asked, is there a way we can structure the rates that would be fair and help customers adopt a heat pump?” said Unitil spokesman Alec O‘Meara. “We recognize that energy affordability is very important to our customers.”

Electric heat pumps are a major part of Massachusetts’ strategy for reaching its goal of going carbon-neutral by 2050. Today, nearly 80% of homes in the state use natural gas, oil, or another fossil fuel for space heating. Looking to upend that ratio, the state has set a target of having heat pumps in 500,000 homes by 2030.

One of the major obstacles to this goal is cost. To address part of this barrier, Massachusetts offers rebates of up to $16,000 for income-qualified homeowners and $10,000 for higher-income residents for heat pump equipment.

The cost of powering these systems though, can be its own problem. Natural gas prices have been trending precipitously downward for the past two years and Massachusetts has long had some of the highest electricity prices in the country. This disparity can be particularly stark in the winter, when consumers using natural gas for heating get priority, requiring the grid to lean more heavily on dirtier, more expensive oil- and coal-fueled power plants, said Kyle Murray, Massachusetts program director for climate and energy nonprofit Acadia Center.

So switching from natural gas to an electric heat source — even a more efficient one like a heat pump — doesn’t always mean savings for a consumer, especially those with lower incomes.

“Electric rates are disproportionately higher than gas rates in the region,” Murray said.

Unitil’s new winter pricing structure is an attempt to rebalance that equation. In New England, electric load on the grid is generally much lower in the winter, when people turn off their air conditioners and switch over to gas or oil heating. That means that the grid, built to accommodate summer’s peak demand, has plenty of capacity for the added load of new heat pumps coming online — no new infrastructure needs to be built to handle this demand (for now, at least).

“The marginal cost of adding demand is lower,” said Mark Kresowik, senior policy director at American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy, which supports heat pump-specific rates.

Unitil, which provides electricity to 108,500 households, decided to let customers share in that lower marginal cost. The company estimates customers will save about six cents per kilowatt-hour, which would work out to a monthly savings of more than $100 for a home using about 2,000 kilowatt-hours per month. The new rate should go into effect in early 2025, O’Meara said.

As Unitil is preparing to deploy its heat pump rate, environmental advocates and other stakeholders are pushing for adoption of this strategy beyond Unitil’s relatively limited territory.

Public utilities regulators are in the middle of considering a rate case filed by National Grid, which serves some 1.3 million customers in Massachusetts. National Grid has proposed what it calls a technology-neutral “electrification rate,” which would provide discounts to certain high-volume energy users, which would include heat pump users.

However, several advocates for low-income households and clean energy — including Acadia Center, Conservation Law Foundation, Environmental Defense Fund, Low-Income Energy Affordability Network — as well as the state energy department and Attorney General Andrea Campbell argue that this approach is inadequate. They’ve submitted comments urging regulators to require National Grid to offer a heat pump rate similar to Unitil’s plan, but modified to work within National Grid’s pricing model.

“Every intervenor in the docket who commented on the electrification proposal in any capacity was negative on it,” Murray said. “And the [department of public utilities] in its questioning seemed fairly skeptical as well.”

National Grid declined to comment on the pending rate case.

The electrification rate, opponents argue, would lower costs not just for households with heat pumps, but also for those with inefficient electric resistance heating and even heated pools, effectively running counter to the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

“The ‘electrification’ proposal would apply to all electricity consumption, whether or not consistent with the Commonwealth’s climate policy of reducing greenhouse gases,” said Jerrold Oppenheim, a lawyer for the Low-Income Weatherization and Fuel Assistance Program Network and the Low-Income Energy Affordability Network.

It would also do nothing to encourage heat pump adoption among low- and moderate-income households, they say: Some 48% of low-income customers interested in switching to a heat pump would actually see bill increases of up to 33%, according to a brief filed by Oppenheim for the network.

Beyond the National Grid rate case, other stakeholders are also pushing for seasonal heat pump rates. The state has convened an Interagency Rates Working Group to study and make recommendations on the challenges of changing how electric rates are designed to encourage electrification of home heating and adoption of electric vehicles. In August the group released an analysis that found seasonal rates created significant savings for homes with heat pumps.

“They came to the same conclusion, that this is the right approach,” Kresowik said.

Eventually, the introduction of advanced metering technology will simplify the process of applying lower rates to desired uses, like heat pumps and electric vehicles. But the full deployment of these systems is still several years in the future, and action to ease adoption of heat pumps must be taken much sooner, advocates argue.

In the meantime, many have expressed some optimism that regulators will require National Grid to make its electrification proposal more responsive to the state’s climate and equity priorities.

“I would be surprised if the electrification pricing proposal exists as is in the final [regulatory] order,” Murray said.

Electric vehicles are an essential solution to decarbonizing transport.

Electric cars tend to have a lower carbon footprint than petrol or diesel cars over their lifetimes. While more carbon is emitted in the manufacturing stage, this “carbon debt” tends to pay off quickly once they’re on the road. The carbon savings are higher in countries with a cleaner electricity mix, and these savings will also increase as countries continue to decarbonize their electricity grids.

How quickly are countries moving to electrified transport? Which countries are leading the way?

In this article, we look at data from across the world on electric vehicle (EV) sales and the stock on the road.

This data comes from the International Energy Agency. It publishes its Global EV Outlook every year. We will update this data every time a new release is published.

Sales of electric cars started from a low base but are growing quickly in many markets.

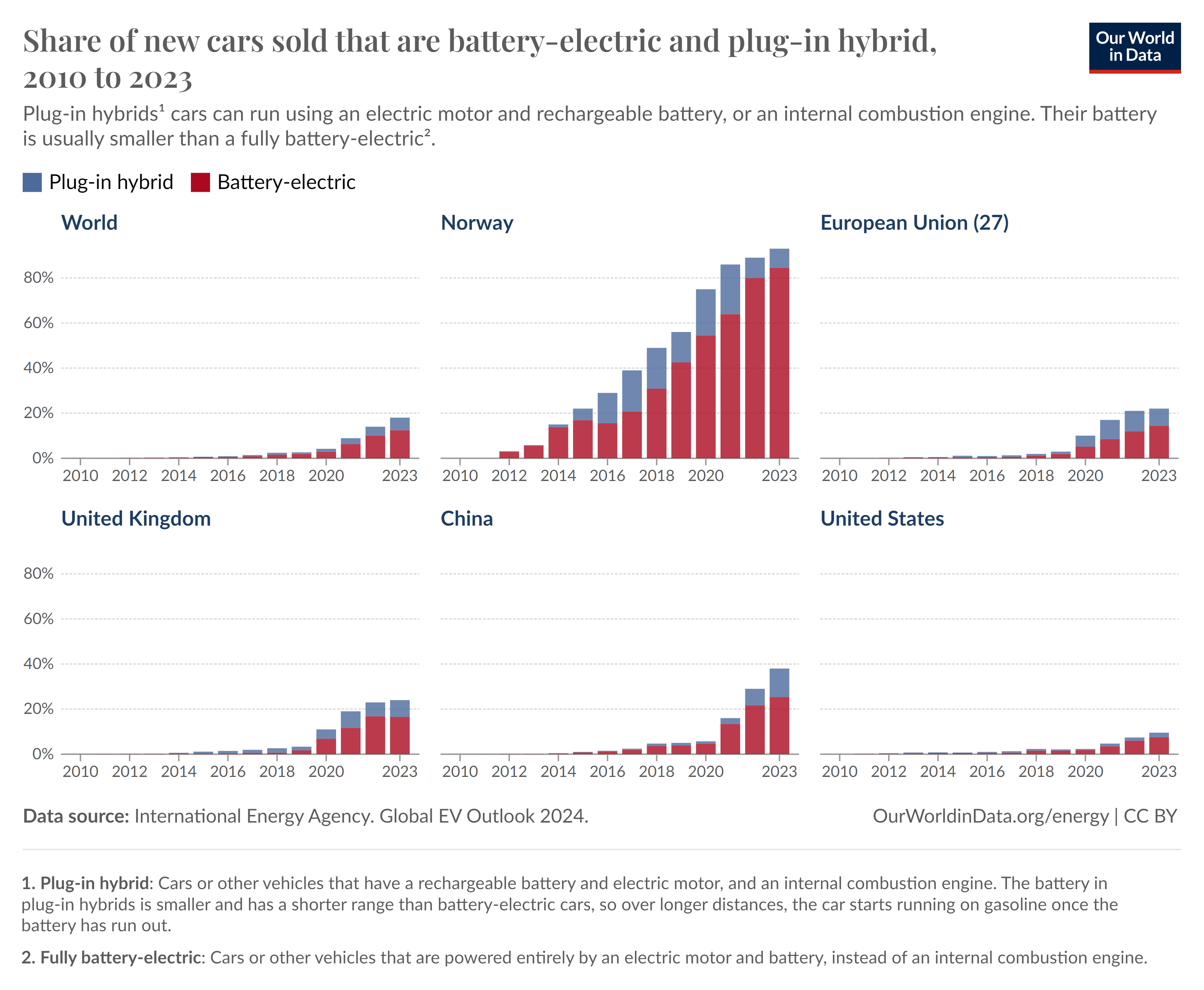

Globally, around 1-in-4 new cars sold were electric in 2023. This share was over 90% in Norway, and in China, it was almost 40%.

In the chart below, you can explore these trends across the world.

Here, “electric cars” include fully battery-electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids.

.png)

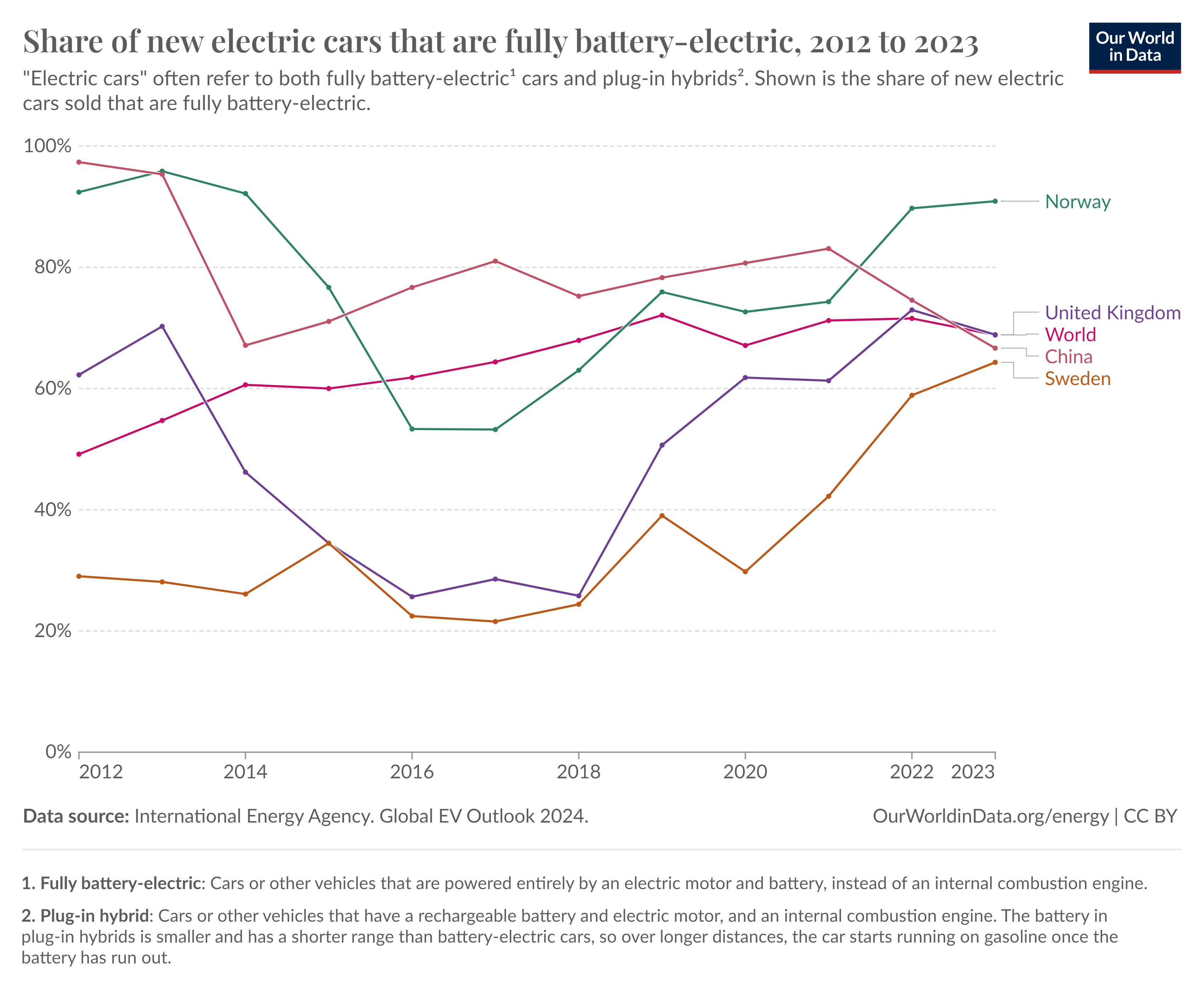

“Electric cars” include battery-electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles. The difference is that fully battery-electric cars do not have an internal combustion engine. In contrast, plug-in hybrids have a rechargeable battery and electric motor, and an internal combustion engine that runs on gasoline.

That means a plug-in hybrid could be driven as a standard petrol car if the owner did not charge the battery. The battery in plug-in hybrids is smaller and has a shorter range than battery-electric cars, so over longer distances, the car starts running on gasoline once the battery has run out.

Since plug-in hybrids will often run on petrol, they tend to emit more carbon than battery-electric cars. However, they do usually have lower emissions than petrol or diesel cars.

In the first chart below you can see electric car sales broken down by these two technologies. This is given as a share of new cars sold each year.

In the second, you will find the share of new electric cars sold that are fully battery-electric.

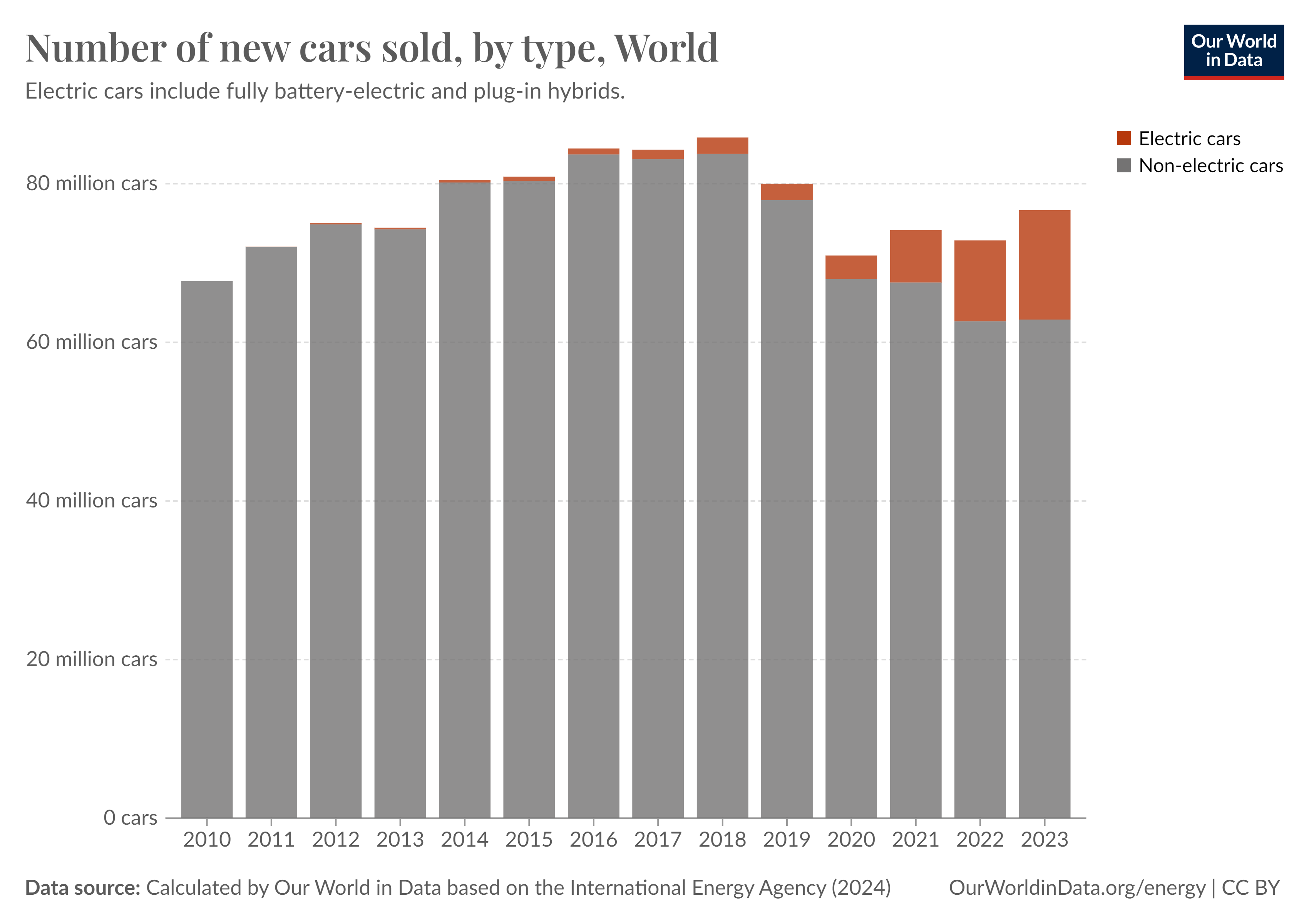

The chart below shows the total number of new electric cars sold. Again, this includes fully battery-electric and plug-in hybrids.

Based on the data published by the IEA on the number of electric cars sold, and EV sales as a share of all new cars, we can calculate the absolute number of new cars of each type sold each year.

These figures suggest that global sales of non-electric cars peaked in 2018. This aligns with other estimates published elsewhere; for example, Bloomberg New Energy Finance reported that sales peaked in 2017.

You can explore this data for other countries in the chart below, too.

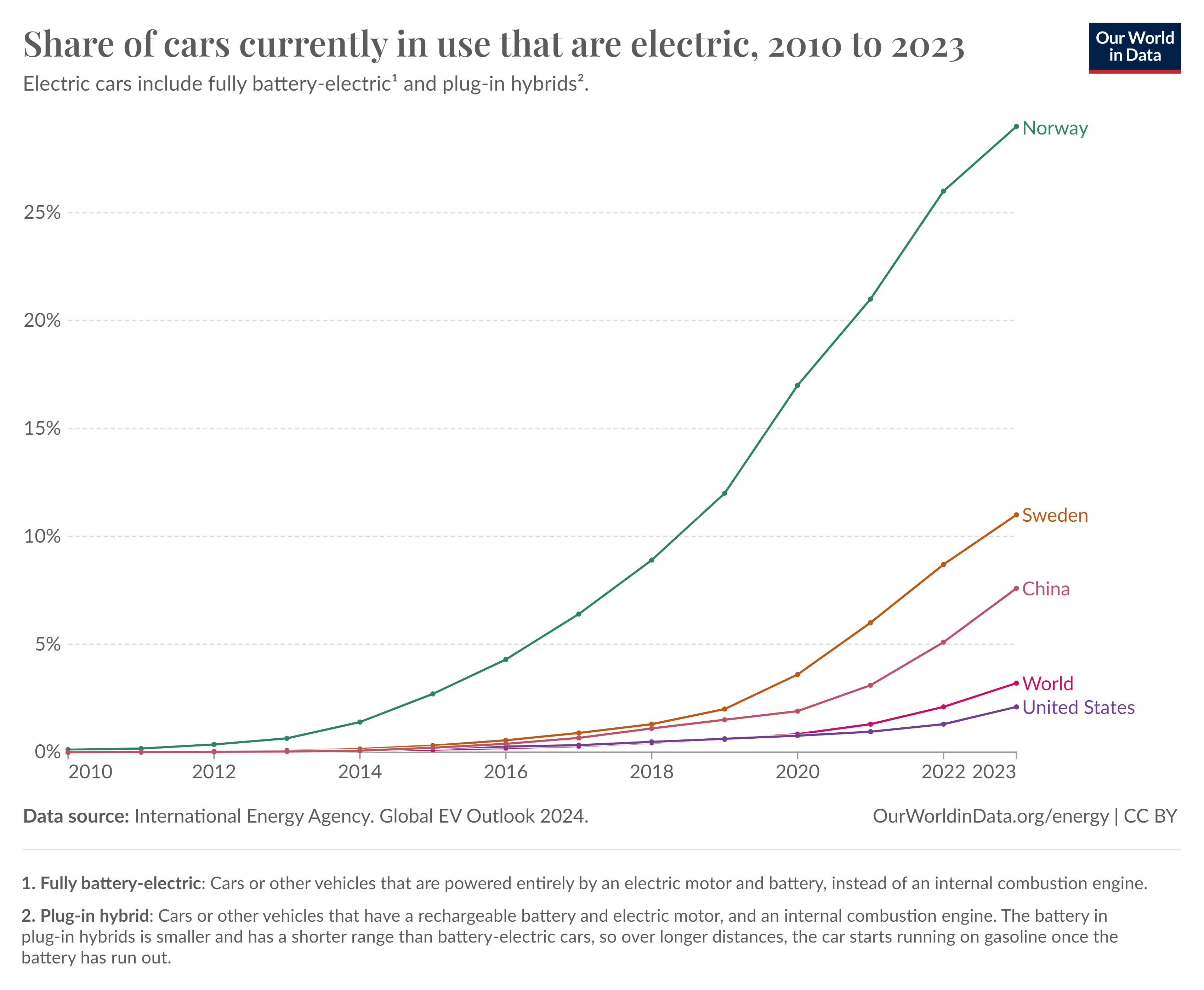

The cars that are on the road today represent sales data over more than a decade.

This can be captured in a metric called “stocks”. It’s an approximation of the number of cars that are in use and represents the balance of cars being added and those that are being retired.

Because people use their cars for a long time, it takes time before new sales have a visible influence on car stocks. That means the share of cars on the road that are electric is much lower than the share among new sales.

The share of cars in use that are electric is shown in the chart below.

The number of electric cars on the road is the cumulative total of sales over the years (minus any cars that have been taken off the road).

The total number of electric car stocks is shown in the chart below. There are now more than 40 million electric cars in use globally, and this is growing quickly. In 2022, this figure was just 26 million.

1. Many studies make this point. Here are just a few:

See Zeke Hausfather’s article in the Carbon Brief. Simon Evans’s fact-check on electric cars, also in the Carbon Brief.

This report is from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

The International Energy Agency’s analysis on the life-cycle footprint.

2. The data below comes from the IEA’s Outlook for 2024.

IEA (2024), Global EV Outlook 2024, IEA, Paris https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024, License: CC BY 4.0.

3. How much lower will depend on someone’s driving and charging habits. If they recharge regularly and run mainly on the battery, its emissions will be much lower. The International Energy estimates that a plug-in hybrid emits half as much carbon as a petrol car per kilometer. But again, there are large uncertainties depending on personal usage.

GRID: New Hampshire utility regulators decide not to allow consumer advocates from that state and Maine to intervene in the review of a widely criticized $385 million transmission line upgrade project because it is an “asset condition” project. (InDepth NH)

SOLAR:

AGRIVOLTAICS: At an orchard at its Hudson Valley research campus, Cornell University plans to experiment with raised solar panels that can be adjusted to shade apple trees during hot weather. (Cornell Chronicle)

TRANSPORTATION: Oral arguments begin today on two lawsuits aiming to restart momentum on the Manhattan traffic congestion tolling program, with one of the involved attorneys saying it’ll be difficult to reduce transportation emissions in New York City without it. (The City)

ELECTRIC VEHICLES: Revel opens its first 24/7 public electric vehicle charging station in Manhattan, with 10 fast chargers offering charge rates up to 320 kW. (electrek)

WORKFORCE: Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey discusses growing the climate workforce in her state, quipping that “whoever figures out this workforce component first, wins.” (Boston.com)

PIPELINES: In Connecticut, environmental activists call on the state’s governor to block a proposed upgrade to a 1,100-mile natural gas pipeline while the expansion plan is still in its early stages. (Fox 61)

FOSSIL FUELS: Stakeholders at a Northeast fuels conference offered differing views of the future role of natural gas, with some claiming it will be “here for the long-term” and others predicting “a future where we are less reliant” on it. (RTO Insider, subscription)

GRID: A PJM Interconnection executive says the pace of new capacity is “nowhere near where we need to be,” with only 2 GW added last year compared to 5 GW the year before. (Utility Dive)

ALSO: Grid operator MISO advances plans for a $21.8 billion portfolio of transmission projects that analysts say could produce up to $23.1 billion in net benefits, partly by limiting the need for new generation. (Utility Dive)

OIL & GAS:

CARBON CAPTURE: U.S. Sen. John Barrasso, a Wyoming Republican, introduces a bill that would increase subsidies for using captured carbon dioxide to stimulate oil and gas production from aging wells. (E&E News, subscription; news release)

CLEAN ENERGY:

WIND: The state of Iowa sues a Washington-state company for allegedly dumping tons of old wind turbine blades around the state, in violation of solid waste laws. (Iowa Capital Dispatch)

SOLAR: University of Pittsburgh researchers interview four dozen rural people, including many farmers, about their views on rural solar development and find that smaller projects that work with the landscape would be more readily embraced. (Inside Climate News)

NUCLEAR:

POLITICS:

ELECTRIFICATION: The Biden administration awards nine tribal nations in Western states nearly $42 million to electrify homes with clean energy. (news release)

This story was originally published by Grist. Sign up for Grist’s weekly newsletter here.

This story was supported by the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

In the dusty light of a decades-old lunch counter in Lewisville, Arkansas, Chantell Dunbar-Jones expressed optimism at what the lithium boom coming to this stretch of the state will mean for her hometown. She sees jobs, economic development, and a measure of prosperity returning to a region that needs them. After waving to a gaggle of children crossing the street in honey-colored afternoon sunshine, the city council member assessed the future as best she could. “Not to say that everything’s perfect, but I feel like the positives way outweigh the negative,” she said.

Lewisville sits in the southwest corner of the state, squarely atop the Smackover Formation, a limestone aquifer that stretches from northeast Texas to the Gulf Coast of Florida and has for 100 years spurted oil and natural gas. The petroleum industry boomed here in the 1920s and peaked again in the 1960s before declining to a steady trickle over the decades that followed. But the Smackover has more to give. The brine and bromine pooled 10,000 feet below the surface contains lithium, a critical component in the batteries needed to move beyond fossil fuels.

Exxon Mobil is among at least four companies lining up to draw it from the earth. It opened a test site not far from Lewisville late last year and plans to extract enough of the metal to produce 100,000 electric vehicle batteries by 2026 and 1 million by 2030. Another company, Standard Lithium, believes its leases may hold 1.8 million metric tons of the material and will spend $1.3 billion building a processing facility to handle it all. All of this has Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders predicting that her state will become the nation’s leading lithium producer.

With so much money to be made, Dunbar-Jones and other public officials find themselves being courted by extraction company executives eager to tell them what all of this could mean for the people and places they lead. They have been hosting town meetings, promising to build lasting, mutually beneficial relationships with the communities and residents of the area. So far, Dunbar-Jones and many others are optimistic. They see a looming renaissance, even as other community members acknowledge the mixed legacies of those who earn their money pulling resources from the ground. Such companies provide livelihoods, but only as long as there is something to extract, and they often leave pollution in their wake.

The companies eyeing the riches buried beneath the pine forests and bayous promise plenty of jobs and opportunities, and paint themselves as responsible stewards of the environment. But drawing brine to the surface is a water-intensive process, and similar operations in Nevada aren’t expected to create more than a few hundred permanent jobs. It’s high-paying work, but often requires advanced degrees many in this region don’t possess. Looking beyond the employment question, some local residents are wary of the companies looking to lease their land for lithium. It brings to mind memories of the unscrupulous and shady dealings common during the oil boom of a century ago.

For residents of Lewisville, which is majority Black, such concerns are set against a broader history of bigotry and the fact that even as other towns prospered, they have long been the last to benefit from promises of the sort being made these days. Folks throughout the area are quick to note that the wealth that flowed from the oil fields their parents and grandparents worked benefited some more than others, even as they lived with the ecological devastation that industry left behind.

Dunbar-Jones is confident that, if nothing else, concern about their reputation and a need to ensure cordial relations with community leaders will sway lithium companies into supporting local needs. “All I can say is right now it’s up in the air as to what they will do,” she said, “but it seems promising.”

Lewisville sits just west of Magnolia, El Dorado, and Camden, three cities that outline the “golden triangle” region that prospered after the discovery of oil in 1920. In an area long dependent upon timber, the plantation economy transformed almost instantly as tenant farmers, itinerant prospectors, and small landholders became rich. Within five years, 3,483 wells dotted the land, and Arkansas was producing 73 million barrels annually.

Although the boom created great wealth, Lewisville remained largely rural, and its residents labored in the fields that made others rich. Still, the oil economy, coupled with the timber industry, brought a rush of saloons, itinerant workers, and hotels to many towns. Restaurants, supermarkets, and other trappings of a middle-class community soon followed, though Lewisville always lagged a bit behind.

That prosperity lasted a bit longer than the oil did. The first wells ran dry by the end of the 1920s, but the Smackover continued producing 20 to 30 million barrels annually until 1967, when it began a steady decline. These days, it offers about 4.4 million a year.

The shops that once served Lewisville and the furniture and feed factories that employed those who didn’t work the fields have long since gone. Jana Crank, who has lived here for 58 years, came of age in the 1960s and remembers prosperous times. She runs a community gallery in what’s left of downtown, where most buildings sport faded paint and cracked windows. “It used to be a TV fix-it shop,” Crank, a retired high school art teacher, said of the space.

As she spoke, a group of friends painted quietly. Canvases showing sunsets, crosses, and landscapes lined the walls. The scenes, bright and cheerful, stood in contrast to Lewisville, where retailers have moved on, the hospital has closed, and the schools have been consolidated to save money. Fewer than 900 people live here, about half as many as during the town’s peak in the 1970s. They tend to be older, with a median household income of around $30,000. “People are just dying out, their children don’t even live in town,” Crank said. “They have nothing to come back for.”

That could change. Jobs associated with mining rare-earth minerals are highly compensated and highly sought-after, many of them netting as much as $92,000 per year. State Commerce Secretary Hugh McDonald believes the state could provide 15% of the world’s lithium needs, and Sanders has said Arkansas is “moving at breakneck speed to become the lithium capital of America.”

A few steps in that direction already have been taken around Lewisville, the county seat of Lafayette County. It is home to 13 lithium test wells, the most in the region. They’re tucked away behind pine trees, fields of cattle, and, occasionally, homes. The dirt and gravel roads leading to them have been churned to slurry by heavy equipment.

Those who own and work the wells arrived quietly last year, their presence indicated by the increasing number of trucks with plates from nearby Texas and Louisiana, sparking rumors throughout the region. They officially announced themselves to Mayor Ethan Dunbar last fall, in visits to local officials, mostly county leaders, to initiate friendly relations and establish the basis for economic partnerships. Mayor Dunbar and the Lewisville City Council were invited to a public meeting where lithium company executives discussed their plans and took questions.

The town’s motto is “Building Community Pride,” something Dunbar-Jones, who is the mayor’s sister, takes seriously. She and others have hosted movie nights, community dinners, and, in a particular point of pride, clinics to help people convicted of crimes get their records expunged. Meanwhile, the city council, joined by a number of residents, has come together to nail down just what the lithium boom will mean for the town and to ensure everyone knows what’s in store.

That’s particularly important, Dunbar-Jones said, because 60% of the town’s residents are Black. “Typically in minority neighborhoods, people are not as aware of what’s going on, because the information just doesn’t trickle down to them the way it does to other people,” she said. “At the meetings with the actual lithium companies, there may be a handful of people of color there versus others. So that lets you know who’s getting that information.”

A representative of Exxon, the only company that responded to a request for comment, said it has strived to build ties with communities throughout the region. “We connect early and often with elected officials, community members and local leaders to have meaningful conversations, provide transparency, and find ways to give back,” the representative said. It has opened a community liaison office in Magnolia and has worked with the city’s Chamber of Commerce to sponsor community events. It also established a $100,000 endowment for Columbia and Lafayette counties to provide grants for “education, public safety, and quality-of-life initiatives.”

Folks in Lewisville would like to see more of that kind of attention. In March, the city, working with the University of Arkansas Hope-Texarkana, hosted a town hall meeting so residents could speak to lithium executives and express concerns. The mayor recalls it drawing a standing room-only crowd that expressed hope that the industry would bring jobs and revenue to town, but also worried about the environmental impact. Folks called on Exxon and other companies to support new housing and establish pathways for young people to work in the industry.

Venesha Sasser, who at 29 is the chief development officer of the local telephone company, sees the coming boom providing an opportunity to build generational wealth for families and resources, like broadband internet access, for communities. Any company that can invest $4 billion in a lithium operation can surely afford to toss a little back, Sasser said. “We want to make sure that whoever is investing in our community, and who we are investing in, actually means our people good.”

Sasser followed a trajectory common among young Black professionals from the area: She left to pursue an education, then returned to care for loved ones. As she got more involved in the community, she often found herself being treated a little differently, an experience Mayor Dunbar delicately described as bumping up against “old systems.” Lewisville is a majority-Black town in a majority-White county, and as of 2022, had a poverty rate of 23%. Although community leaders say they work well with colleagues in other towns and with county leaders, they also feel that they’ve had to elbow their way into conversations with lithium companies. They worry that the dynamics of the oil days, when Black men worked alongside whites but often in lower-paying, less desirable jobs and most of the money stayed in wealthier cities like El Dorado, will repeat themselves.

“You had people from Magnolia and El Dorado and Spring Hill and other places coming in and doing the work and reaping the benefits, and then when it was gone, they were gone,” said Virginia Henry, a retired school teacher who grew up in Lewisville and lives in Little Rock. Her ex-husband drilled for oil years ago, and the experience left her with a sour taste in her mouth. “I’m thinking it’s going to be pretty much the same,” she said. “They’re going to ease in, they want to do all this work and create all these jobs for somebody and then ease out when it’s done in a few years. Then here we’ll be with soil that can’t grow anything, contaminated water, and a whole bunch of kids with asthma.”

Mayor Dunbar, who is midway through his second term, is trying to balance reservations with optimism. “‘Imagine the possibilities.’ That’s my tagline,” he said, settling into a chair at City Hall. A blackboard behind him outlined his priorities: housing, recreation, education. He hopes support from companies like Tetra Technologies, which is developing a 6,138-acre project not far away, will finance those goals and give people a future that’s more stable than the past, one in which Lewisville’s children can pursue the same opportunities that kids in nearby, better-resourced communities can.

“Think about Albemarle in Magnolia,” he said, referring to the bromine plant about 30 miles up the road. “Get a job at Albemarle, you stay there 25 years, you earn a decent salary, you’d have a decent retirement. You can live well. Quality of life is good. We are hoping to see the same thing here.”

Many of the people poised to benefit from the lithium beneath their feet seem ambivalent about climate change. In El Dorado, in a bar called The Mink Eye, an oil refinery worker grimaced at the mention of electric vehicles. The next morning, retired oil workers gathered at Johnny B’s Grill scoffed at the idea of a boom. A waitress admitted that she’d bought stock in lithium companies, but said any faith that the industry will bring renewed prosperity does not necessarily mean folks are on board with the green transition. “These men drive diesels,” she said, pointing toward her customers. Still, she said, any jobs are good jobs.

That attitude pervades the state capitol in Little Rock, where politicians who don’t give much thought to why the energy transition is necessary cheer the state’s emerging role in it. The governor, who has cast doubt on human-caused climate change, has appeared at industry events like the Arkansas Lithium Innovation Summit to proclaim the state “bullish” on its reserves of the element. “We all knew that towns like El Dorado and Smackover were built by oil and gas,” Sanders told the audience. “But who knew that our quiet brine and bromine industry had the potential to change the world.”

Much of the world’s lithium is blasted out of rocks or drawn from brine left to evaporate in vast pools, leaving behind toxic residue. The companies descending on Arkansas plan to use a more sustainable method called direct lithium extraction, or DLE. It seems to be a bit more ecologically friendly and much less water-intensive than the massive pit mines or vast evaporation ponds often found in South America. It essentially pumps water into the aquifer, filters the lithium from the extracted brine, then returns it to the aquifer in what advocates call a largely closed system. Researchers from the University of California, Los Angeles, in a report prepared for the Nature Conservancy, said that “DLE appears to offer the lowest impacts of available extraction technologies.”

Still, the technology is relatively new. According to Yale Environment 360, Arkansas provides a suitable proving ground for the approach because it has abundant water, a large concentration of lithium, and an established network of wells, pipelines, and refineries. But there are concerns about the amount of water required and the waste material left behind, despite repeated assurances from lithium companies that the process is safe and sustainable.

Although DLE doesn’t require as much water as brine evaporation, in which that water is lost, “it is a freshwater consumption source,” Patrick Donnelly, of the Center for Biological Diversity, said in an interview with KUAF radio in Fayetteville, Arkansas. The waste generated by the process is another concern, he said, “in particular, a solid waste stream. It’s impossible for them to extract only the lithium.”

Locals are well aware of the impact brine can have on the land. Before anyone realized its value, oil and gas producers didn’t worry much about it leaking or spilling onto the ground, literally salting the earth. Some are concerned that the pipelines that will carry brine to refineries might leak, as they did in the oil days. Such fears are compounded by the fact the state Department of Environmental Quality relies on individuals to report problems and doesn’t appear to do much outreach to residents.

There’s also a lot of skepticism about how many jobs the boom may create. So far, Standard Lithium’s plant in El Dorado employs 91 people, said Douglas Zollner, who works with the Arkansas branch of the Nature Conservancy and has toured the facility. No one’s offered any projections on how many people might find work in the budding industry, but a lithium boom in Nevada suggests it may not be all that many. Construction of the Thacker Pass mine, which could produce 80,000 metric tons of lithium annually, is expected to generate 1,500 temporary construction and other jobs — but it will only employ 300 once operational.

Those jobs pay well, but typically require advanced training. Public universities like Arkansas Tech University are revising science and engineering curricula to meet the lithium industry’s needs, hoping to connect students with internships in the field. However, locals worry that disinvestment in schools in rural and largely Black communities will leave those who most need these jobs unable to attain the training necessary to land them.

Just how much money might flow into local communities remains another open question. Fossil fuel companies lease the land they drill and pay landowners royalties of 16.67% of their profit. Any oil pumped from the land also is taxed at 4 to 5% of its market value. This fee, called severance tax, is paid to the counties or towns from which the resource was extracted.

None of these things apply to lithium. So far, there is no severance tax on the metal, though the state levies a tax of $2.75 for every 1,000 barrels of the brine from which it is extracted. The state Oil and Gas Commission continues haggling over a royalty rate, though it seems unlikely the fee will be as high as those paid on oil and gas leases. When the state sought a double-digit royalty, the industry balked, arguing that extracting and processing lithium is expensive and officials ought to wait until production begins in earnest before deciding what’s fair.

Companies cannot extract and sell the metal for commercial use until the commission sets a royalty rate, a process expected to drag on for some time. On July 26, the major players in the Arkansas lithium industry filed a joint application seeking a rate of 1.82%. The South Arkansas Mineral Association — which represents the majority of landowners, which is to say, timber companies, oil companies, and other corporate interests — demanded a higher share.

Small landowners still hope to benefit, and the lack of clarity around royalties hasn’t done much to engender trust among locals wary of the companies looking to lease their land. Some folks, already offered terms, are using online forums to determine if they’re being stiffed. Others fear efforts to wrest land from the few Black families who own property, often passed between generations informally without a deed or title. Such land, called heirs’ property, accounts for more than one-third of Black-owned property in the South, and without the documentation required to prove ownership, land can be subject to court-ordered sales.

Many in Lewisville say they regularly receive calls and texts from people interested in buying land, and Henry has seen people checking out properties and attending auctions. During a visit to the Lafayette County courthouse archives, I noticed a woman thumbing through mineral rights records. Although she wouldn’t identify herself, she politely explained that she was checking such documents throughout Arkansas, Texas, and Louisiana, bringing to mind the speculators who, during the oil boom, did the same before approaching naive residents who may not know about the riches under their land.

Beyond the timber companies with holdings in the region, most of the major landowners are white and wealthy, and any spoils, Henry suspects, will simply pass from one affluent family or powerful company to another, with no benefit to people like her. “What land, honey?” she said with a small, sardonic laugh. “That’s a pie in the sky type dream to me.”

Despite the concerns, the hype and fanfare surrounding the possibility of an economic revival remains high. City officials in Lewisville, and the people they lead, are trying to remain open-minded and easygoing even if unanswered questions linger about how many jobs might be coming, how the boom will benefit their town, and what it will mean for the environment.

“You know, it’s kind of frustrating because the questions get asked at these meetings,” Dunbar, the mayor, said. But he feels the lithium companies often meet questions with the same pleasant, if unhelpful, answer of “We can’t talk about it.” They’re always so careful in their responses. “They deliberately did not say anything until they knew what they wanted to do and say, that’s the same with what they want to provide communities,” Dunbar said.

As for the $100,000 commitment from Exxon, no one’s sure exactly who will receive that money or how allocations will be made. The mayor, discussing that point, showed some frustration. He said he has tried, and will continue to try, to get the companies to put their promises of jobs and support for local infrastructure in writing.

The balance of goodwill that he is trying to maintain between everyone involved is delicate: the lithium companies, whose jobs and support his community desperately needs; the county officials he must work with; the residents of Lewisville; and the mayors he collaborates with on grant applications. These towns are small, and word spreads quickly; relationships are as precious as the riches deep below the ground.

As Dunbar-Jones, the city council member, finished her turkey sandwich in the late afternoon light of the diner, she spoke of her faith in the ties between the people of Lewisville. “It’s hard to get a group of people to work together, period, especially when they don’t know each other,” she said. “But we all know each other.”

Despite her confidence, she knows she’s dealing with relationships in which companies take what they can and leave, where the question of what they owe the communities that enrich them is naive. Her father benefited from his job at Phillips 66, but it couldn’t last forever. When the oil was gone, those who profited from it were, too. From their perspective, she said, it’s a question of “How long am I going to support a community I’m no longer in? It would be unrealistic to think that there will be some long-term benefits from it.” The same is true of lithium, and the companies that will mine it. At some point, they will leave, and take their jobs and their money with them. Dunbar-Jones only hopes they leave Lewisville a little better off once they’ve left.

Editor’s note: Climeworks is an advertiser with Grist. Advertisers have no role in Grist’s editorial decisions.

This article originally appeared in Grist, a nonprofit, independent media organization dedicated to telling stories of climate solutions and a just future. Learn more at Grist.org

The UK’s last coal-fired power plant, Ratcliffe-on-Soar in Nottinghamshire, will close this month, ending a 142-year era of burning coal to generate electricity.

The UK’s coal-power phaseout is internationally significant.

It is the first major economy – and first G7 member – to achieve this milestone. It also opened the world’s first coal-fired power station in 1882, on London’s Holborn Viaduct.

From 1882 until Ratcliffe’s closure, the UK’s coal plants will have burned through 4.6bn tonnes of coal and emitted 10.4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) – more than most countries have ever produced from all sources, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

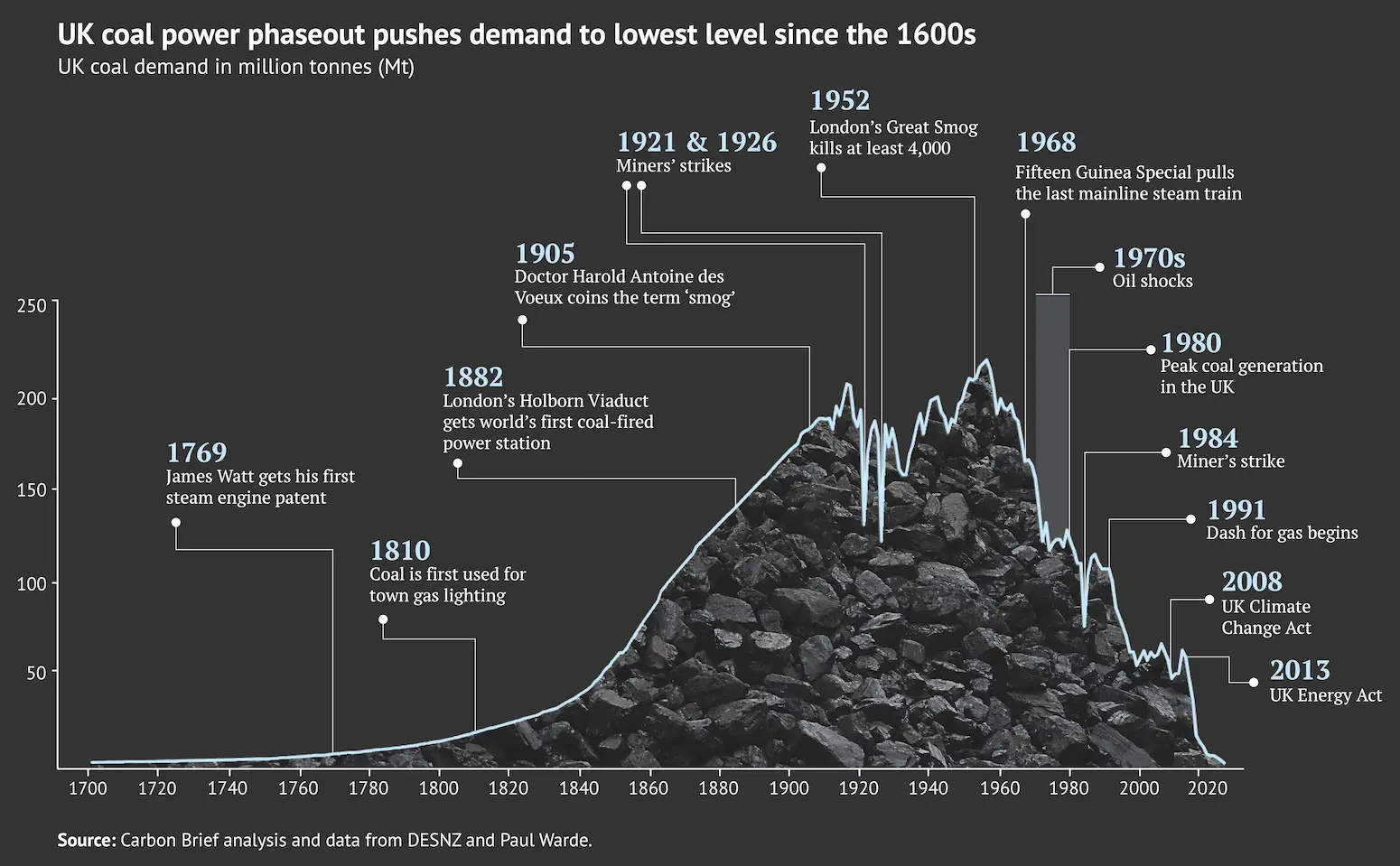

The UK’s coal-power phaseout will help push overall coal demand to levels not seen since the 1600s.

The phaseout was built on four key elements.

First, the availability of alternative electricity sources, sufficient to meet and exceed rising demand.

Second, bringing the construction of new coal capacity to an end.

Third, pricing externalities, such as air pollution and carbon dioxide (CO2), thus tipping the economic scales in favour of alternatives.

Fourth, the government setting a clear phaseout timeline a decade in advance, giving the power sector time to react and plan ahead.

The UK’s experience, set out and explored in depth in this article, demonstrates that rapid coal phaseouts are possible – and could be replicated internationally.

As the UK aims to fully decarbonise its power sector by 2030, it has the challenge – and opportunity – of trying to build another case study for successful climate action.

The UK’s resource endowment has long included abundant coal, which had been used in small quantities for centuries. Coal use for electricity generation only came much later.

Over the centuries, surface coal deposits had been exhausted and mining became a necessity, despite the dangers of subsurface flooding, rock collapse and noxious gases.

The earliest steam engines, in use from around 1700, burned coal to pump water out of mines, enabling deeper coal deposits to be accessed.

These steam engines were very inefficient, but improvements by inventors including James Watt and George Stevenson made the use of coal more economical – and more widespread.

(This effect, whereby greater efficiency reduced costs, which, in turn, raised demand and fueled greater use of coal, despite higher efficiency, became known as the Jevons paradox.)

As a result, UK coal use began to surge as shown in the chart below, helping to power the Industrial Revolution, the British empire – and an explosion in global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Dr Ewan Gibbs senior lecturer in economic and social history at the University of Glasgow and author of “Coal Country: The Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialization in Postwar Scotland”, says:

“The way the UK’s Industrial Revolution unfolded, coal was absolutely pivotal to becoming the industrial economy that Britain developed in the 19th century. The steel industry was powered by coal. And over the late 18th – and certainly in the first half of the 19th century – Britain became a coal power economy. It was the world’s first coal-fired economy.”

This is before looking at the coal mining industry and its role in the British Industrial Revolution, adds Gibbs, which employed more than a million miners at its peak and shaped the industrial economy of large regions of the country.

In 1810, coal began to be used for town gas for lighting and from 1830 it was used to fuel the expansion of the railways as they snaked across Britain.

It was in 1882 that coal was first used to generate electricity for public use. In January of that year, the world’s first coal-fired power station began operating at Holborn Viaduct in London.

Built by the Edison Electric Light Station company, the “1,500-light” generator, known as Jumbo, supplied electricity for lighting to the viaduct and surrounding businesses until 1886. It was hailed by Edison himself as a success.

These new uses – supplying heat, light and locomotion, in addition to industrial energy – helped drive a steep uptick in the use of coal in the UK. Demand grew more than tenfold from 14.9m tonnes (Mt) in 1800 to 172.6Mt by 1900.

Small coal-fired power plants were being opened around the UK during this period, including the Duke Street Station in Norwich. Opened in 1893, the site provided lighting for the Colman’s mustard factory on Carrow Road and surrounding area.

Despite surging domestic demand, the UK also became the “Saudi Arabia of 1900”: coal was its largest bulk export and it was the biggest energy exporter in the world until 1939.

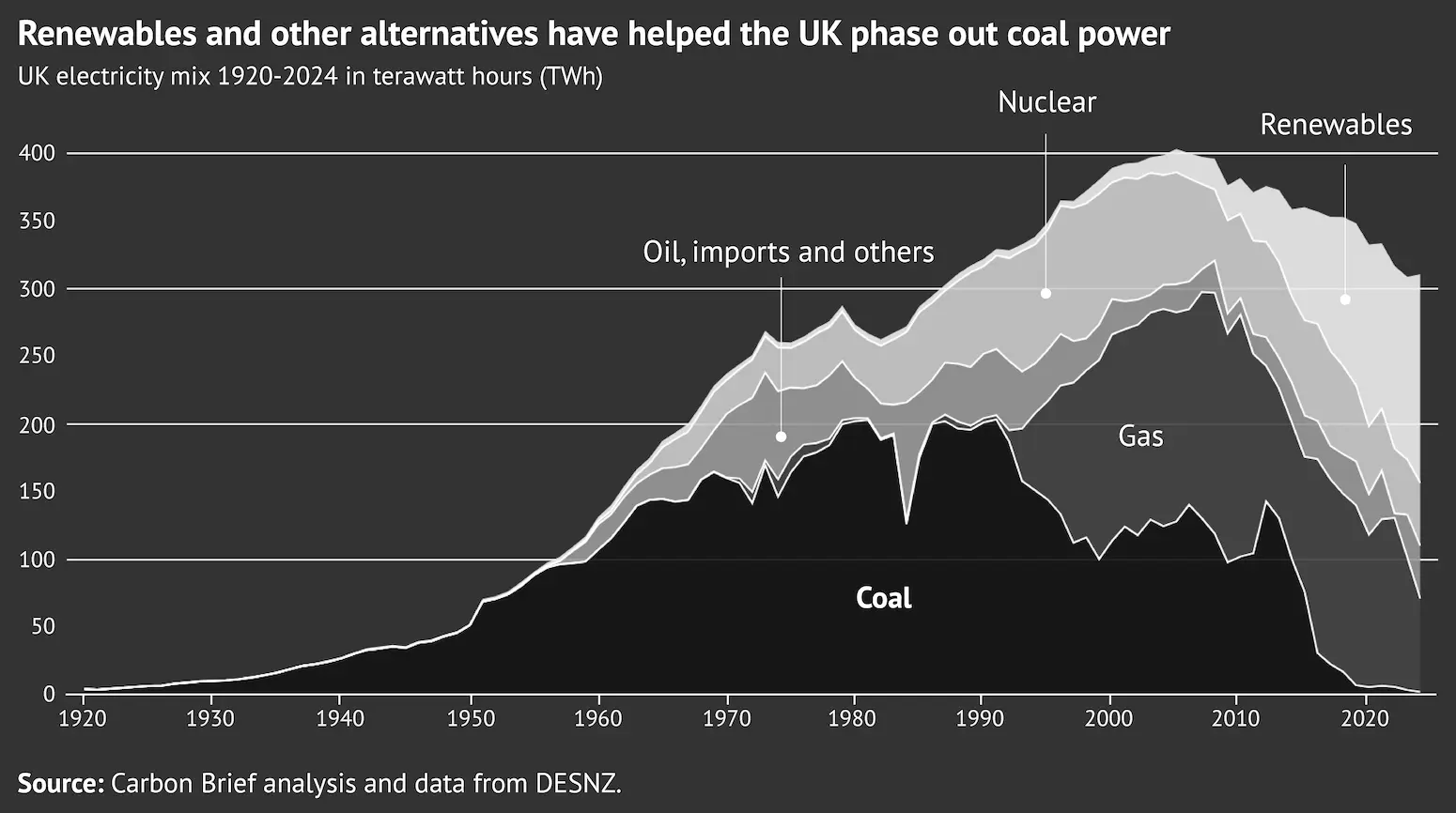

By 1920, the UK was generating 4 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity from coal, meeting 97% of national demand – the bulk of which came from factories.

It was around this time that the first hydropower plants were also being built in Scotland, although most were used to directly power nearby aluminium plants. As industries such as this continued to grow in the UK, so too did the demand for electricity.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the use of coal continued to expand in the UK, despite notable blips driven by miners strikes in the 1920s and the Great Depression between 1929 and 1932.

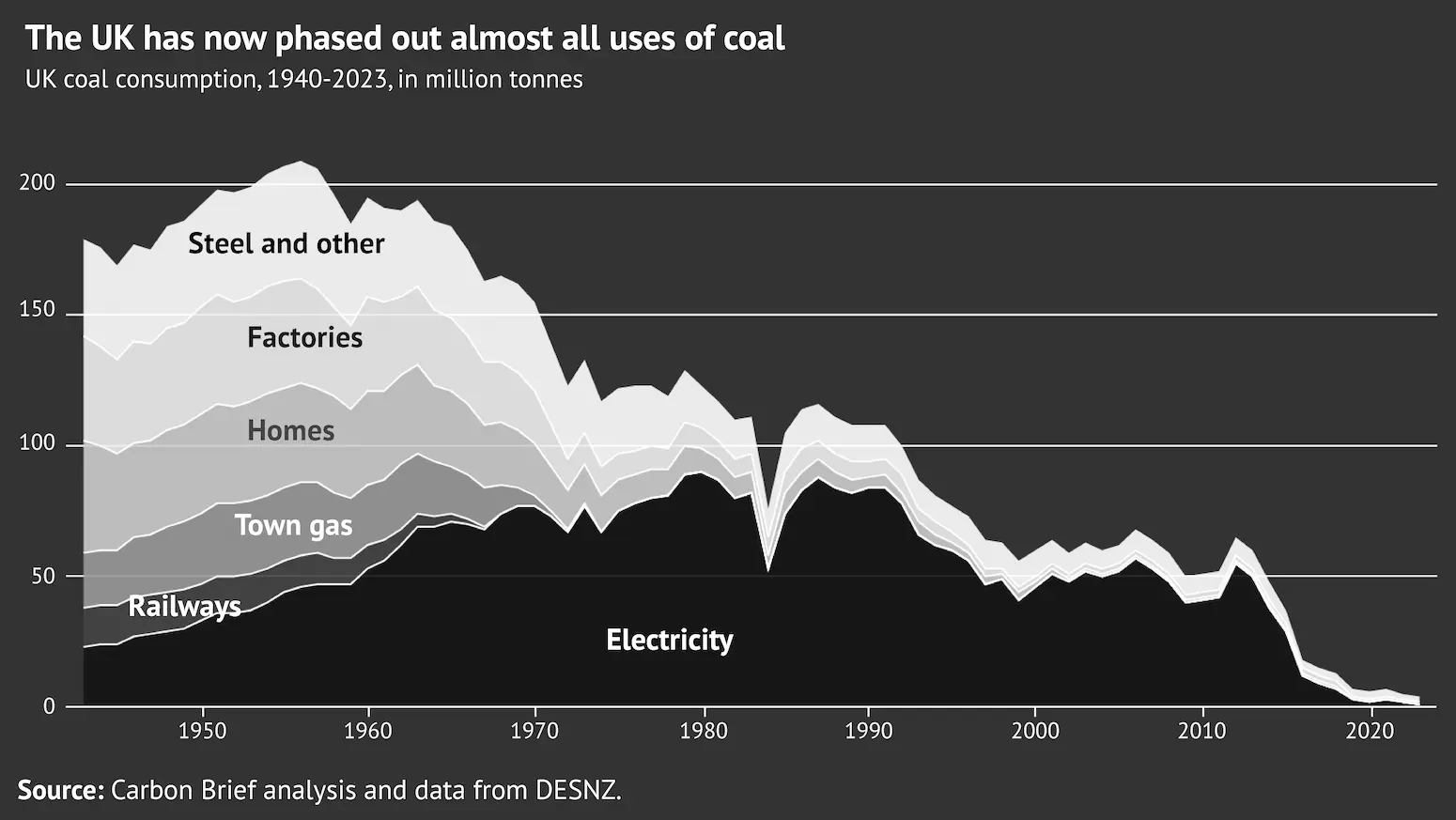

By the time UK coal use had reached its peak of 221Mt in 1956, however, coal power was still only a small fraction of demand. Steelmaking, industry, town gas, domestic heat and the railways dominated, as shown in the chart below.

Over the second half of the 20th century, all of these uses – except power – declined steeply.

Reasons for the decline in UK coal use in this period include the advent of North Sea gas and the end of steam railways, as well as increasing globalisation and deindustrialisation.

The coal mining workforce dropped from more than 700,000 in the 1950s to less than 300,000 by the mid-1970s. However, these losses occurred as part of a fairly “just transition”, as mining jobs were replaced by those in manufacturing, Gibbs says.

After the mine closures that triggered the 1984 strikes, mining jobs fell again to less than 50,000 by 1990. Many former coal mining communities remain impoverished and this period has been cited as a “failed just transition” for coal workers.

Another key factor in the post-war coal decline was that, by the 1950s, the environmental impact of burning coal was becoming too obvious – and dangerous – to ignore.

As early as the 1850s, pollution from burning coal in London’s homes and factories had started causing “pea-souper” days – when a greenish fog settled over the city. In 1905, Irish doctor Harold Antoine des Voeux had coined the term “smog” while working in London.

But events came to a head in December 1952. As winter temperatures began to bite, the people of London stoked their coal fires. An anticyclone weather pattern caused cold, still conditions, trapping polluted air over the city.

Smoke from fires mingled with pollution from factories and other sources dotted across London, creating what became known as the “Great Smog”.

Lasting for four days, the fog was up to 200 metres thick, according to the Met Office. Conditions were worst in London’s East End, which was home to a large number of factories powered by coal.

During this period, around 1,000 tonnes (t) of smoke particles, 2,000t of CO2, 140t of hydrochloric acid and 14t of fluorine compounds were emitted per day in London, according to the Met Office. Additionally, “and perhaps most dangerously”, 370t of sulphur dioxide was converted into 800t of sulphuric acid, it adds.

About 4,000 people are known to have been killed by the Great Smog, although it could have been many more. Hospitalisations increased by 48%, instances of asthma grew in exposed children and the city was disrupted for days.

Three years later, parliament responded with the 1956 Clean Air Act. This outlawed “smoke nuisances” or “dark smoke” and set limits for what new furnaces could emit. Laws around emissions were further strengthened in 1968.

The decades that followed saw the use of coal for domestic heating, rail travel and industry continue to decline as cheaper and cleaner alternatives began to take over.

These years also saw a shift away from small coal plants in cities towards large-scale power plants in rural areas, closer to coal mines. While the UK was also pioneering nuclear power, it was not until 1957 that coal’s share of annual electricity generation fell below 90% for the first time.

Between 1960-64, the Central Electricity Generating Board (CEGB) unveiled plans for 10 coal-fired power stations using 500 megawatt (MW) “turbo-generator” units. These projects formed a wave of new coal plants that were opened between 1966 and 1972.

Construction of these projects saw coal capacity climbing to an all-time peak of 57.5GW in 1974. Coal generation peaked a few years later in 1980, at 212TWh, but by this time – with electricity demand rising rapidly – it only made up 76% of electricity supplies, as oil and nuclear power had eroded its market share.

The UK’s last new coal-fired generating capacity was at Drax, which had opened in 1975 as a 2GW plant, but was doubled to 4GW in 1986.

By 1990, despite significant growth in nuclear capacity in the previous decade, coal still made up 65% of the UK’s electricity mix.

The combination of the Clean Air Act, the switch from town gas to North Sea gas, deindustrialisation and globalisation had all helped drive down the use of coal in the second half of the 20th century.

But, as noted above, coal power continued to thrive for much of this period, as alternative sources of electricity generation failed to keep up with rising demand.

As a result, coal generation did not peak until 1980 – and remained at similar levels in 1990.

Then, after a century dominating UK electricity supplies, coal was phased out in two rapid and distinct stages, punctuated by a plateau that lasted more than a decade.

The first stage was the “dash for gas” of the 1990s.

The second stage saw the buildout of renewables, rising energy efficiency and policies to make coal plants pay for their pollution.

From the 1950s, the expansion of nuclear and oil-fired power-plants had begun to erode coal’s share of the UK electricity mix. Still, coal-fired electricity generation continued to grow throughout the 1960s and 1970s as coal-fired power stations were built up and down the country. This included Ratcliffe-on-Soar, the UK’s last operating coal-fired power plant, which was commissioned in 1968 by the CEGB.

While gas had been discovered in the North Sea in the 1960s, its large-scale use for electricity generation was ignored and restricted for many years.

With the exception of 1984 – when oil power helped keep the lights on during the miners’ strike – coal generation continued to hold steady through the 1980s.

By the end of that decade, however, coal power was about to enter its first stage of decline.

Amid rising concern about acid rain, the EU passed the 1988 Large Combustion Plant Directive (LCPD), requiring reductions in sulphur dioxide emissions. Coal plants were a major source, with abatement technology added to their running costs.

At the same time, ”combined cycle” gas turbine technologies were advancing and gas prices were falling, making gas not only cleaner, but also cheaper than coal.

The ensuing dash for gas within the newly privatised electricity sector saw coal-fired generation roughly halve in a decade. It fell from more than 200TWh and 65% of the total in 1990 to just over 100TWh and 32% in 2000 – with gas power going from near-zero to nearly 150TWh over the same period.

Following the turn of the century, the UK’s coal power entered a period of stagnation, with its output rising, then falling and rising again, in response to the ebb and flow of gas prices.

In 2000, the UK’s now-defunct Royal Commission on Environmental Pollution had published a report on energy and the “changing climate”. It called on the government to cut UK greenhouse gas emissions to 60% below 2000 levels by 2050, including via a “rapid deployment of alternative energy sources” to replace fossil fuels.

By the time of the 2003 energy white paper, the “60% by 2050” target was government policy, as was a goal for 10% of electricity to be renewable by 2010, supported by a “renewables obligation”. New nuclear was “not rule[d] out” – but it remained uncertain.

Yet the 2003 white paper also left the door open to “cleaner coal” using carbon capture and storage (CCS). And it proposed government-backed investment in new coal reserves.

It was to take another decade, including a range of new policy developments, a major protest movement and an unexpected – but highly significant – decline in electricity demand, before UK coal power would enter the second stage of its phaseout.

One such policy development was the 2005 entry into force of the EU Emissions Trading System (EUETS), the world’s first major carbon market. It was initially ineffective – carbon prices crashed, particularly in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis – but the EUETS established the principle that polluting power plants should pay for their CO2 emissions.

Another notable policy was the 2001 update to the EU’s LCPD, which set out tighter limits on air pollution from power plants and came into force in 2008.

Many of the coal-fired power plants in the UK were old by this point and opted to use a “derogation” (exemption) that allowed continued operation until 2015, without the need to invest in pollution control equipment, if they only operated for a limited number of hours.

While this sealed the fate of a raft of older plants, the prospect of new coal-fired capacity in the UK was very much still on the agenda at this point.

In late 2007, the “Kingsnorth six” scaled the chimney of an existing coal plant in Kent to protest against plans for a new station at the site. In January 2008, the local council approved the plans for what would have become the UK’s first new coal plant for 24 years.

In October 2008, the UK passed the Climate Change Act, including a legally binding target to cut greenhouse gas emissions to 60% below 1990 levels by 2050 – later strengthened to 80% and then, in 2019, to “net-zero”.

Sean Rai-Roche, policy advisor at thinktank E3G, tells Carbon Brief that the Act, as the first legally binding climate goal set by a country, was a “seminal moment” in the UK’s journey, including its coal phaseout.

By 2009, then-energy and climate secretary Ed Miliband – now secretary of state for energy security and net-zero – announced that no new coal plants would be built in the UK without CCS.

“The era of new unabated coal has come to an end,” Miliband stated at the time.

Yet the Labour government continued to back new coal with CCS, describing it as part of a “trinity” of low-carbon electricity sources along with new nuclear and renewables.

It was only towards the end of 2009, when developer E.On postponed its Kingsnorth plans, that protestors were able to claim their “biggest victory” for the UK climate movement.

The Kingsnorth plant was formally cancelled the following year and no new coal projects were ever built again in the UK, paving the way for an early phase out as old plants retired.

(In contrast, countries including the US and Germany built a wave of new coal capacity around 2010, locking themselves in to continued use of the fuel for longer periods.)

After 2010, with no new coal plants built in the UK and with many older sites set to close rather than making costly upgrades to meet tighter air pollution rules, coal power was primed for the second stage of its phase out – but not before alternative generation was available.

The 2013 Energy Act formalised the end of unabated coal power with an emissions performance standard (EPS). This set a limit of 450g of CO2 per kilowatt hour for new power plants – around half the emissions of unabated coal.

Dr Simon Cran-McGreehin, head of analysis at thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU), tells Carbon Brief that the combination of air-pollution rules, the cost of CCS and carbon pricing has made ongoing coal generation “uncompetitive”. He says:

“Ongoing coal power simply isn’t an option, as it would have such high costs…that it would be uncompetitive with even gas and nuclear, let alone new renewables.”

The 2013 Energy Act also revived plans for new nuclear, leading to the construction of Hinkley Point C in Somerset, and created “contracts for difference” to support the expansion of low-carbon generation.

Renewable generation went on to double in the space of five years, from around 50TWh in 2013 to 110TWh in 2018. Renewables are on track to generate more than 150TWh in 2024.

The coalition government also introduced the “carbon price floor” in 2013, which added a top-up price to CO2 emissions from the power sector and tipped the scales in favour of gas over coal.

This additional carbon price had a “significant effect” on UK coal power, according to thinktank Ember, helping drive a sharp reduction in generation over the years that followed.

Coal dropped from nearly 40% of the UK electricity mix in 2012 to 22% in 2015.

In addition to the growth of renewables, an additional factor allowing the rapid phaseout of UK coal generation has been the fall in electricity demand since 2005.

Indeed, by 2018, demand had fallen to levels not seen since 1994, saving some 100TWh relative to previous trends – equivalent to the output of four Hinkley Point Cs.

Electricity demand has declined thanks to a combination of energy efficiency regulations, LED lighting and the offshoring of some energy-intensive industries.

The rapid pace of progress meant that, by 2015, then secretary of state for energy and climate change Amber Rudd was able to announce a target to phase out coal by 2025.

Speaking at the Institution of Civil Engineers, Rudd said:

“It cannot be satisfactory for an advanced economy like the UK to be relying on polluting, carbon-intensive 50-year-old coal-fired power stations. Let me be clear: this is not the future.”

The following year, in 2016 – after the last plant closures due to the EU’s LCPD – coal power dropped precipitously to just 9% of annual electricity generation.

That year also witnessed the first hour with no UK coal power since the Holborn Viaduct plant had opened in 1882. This was followed in 2017 by the first full day without coal power, in 2019 by the first week without the fuel and, in 2020, by the first coal-free month.

The coal phaseout target was then brought forwards in 2021 to October 2024, with just 1.8% of the electricity mix having come from coal in 2020.

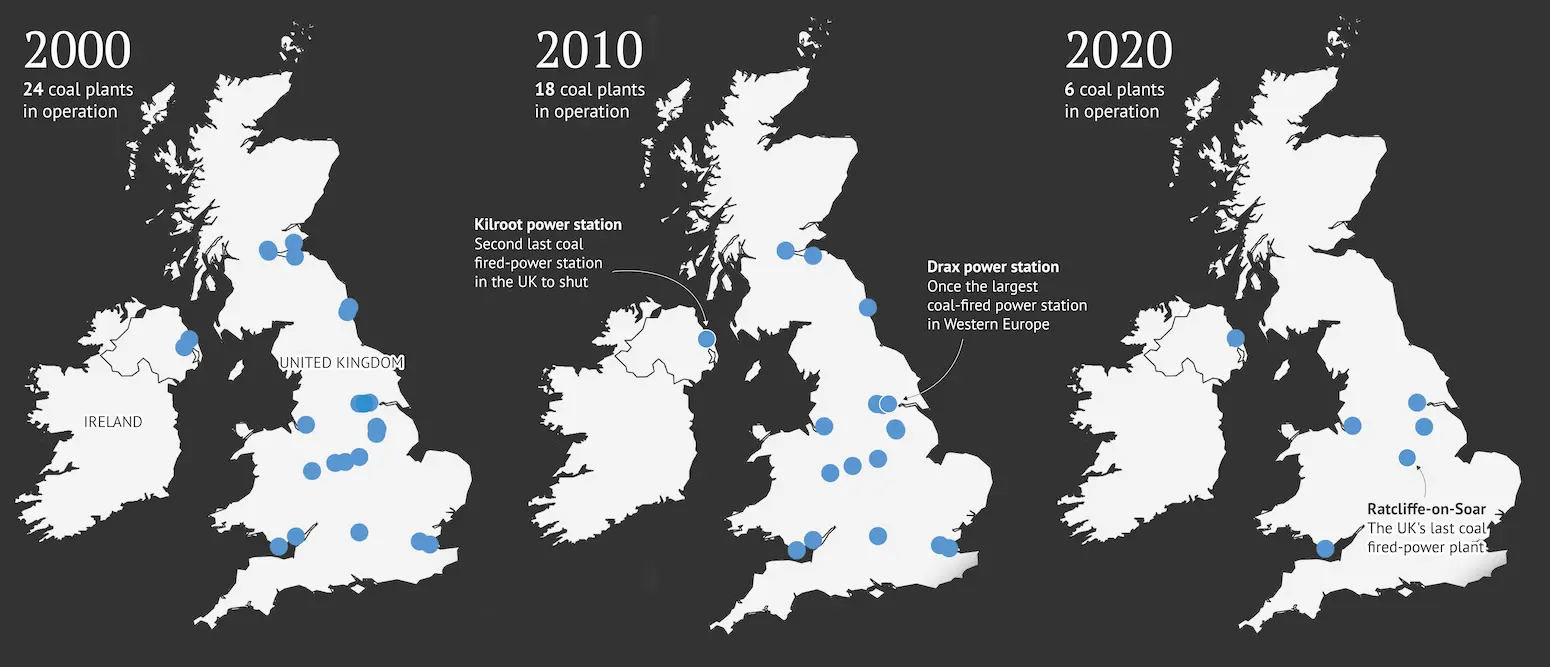

Coal plants continued to shutter throughout this period, as shown in the maps below. SSE’s last coal-fired power station, Fiddler’s Ferry, and RWE’s Aberthaw B station closed in March 2020. Drax’s two remaining coal units and EDF’s West Burton A all closed in March 2023.

(Four of the six coal units at Drax have been converted to burn biomass – mostly wood pellets imported from North America – with uncertain climate impacts. It generates around 14TWh of electricity per year from these units, roughly 4% of the UK total.)

Then, in late 2023, the UK’s second-last coal-fired station – Kilroot in Northern Ireland – stopped generating electricity from coal, leaving just one plant remaining.

These closures left Ratcliffe-on-Soar as the only operating coal-fired power station in the UK in 2024, with coal having met just over 1% of demand in 2023.

On 28 June 2024, the last coal delivery to Ratcliffe took place, a “landmark moment” in the country’s coal journey. The shipment of 1,650 tonnes of coal was only enough to keep it running for a matter of hours.

At full capacity, the 2GW Ratcliffe would have needed roughly 7.5Mt of coal each year, the burning of which would have produced around 15MtCO2.

Ratcliffe’s closure by 1 October will bring to an end 142 years of coal power in the UK. And, contrary to scores of misleading headlines over the years, the lights have stayed on.

Remarkably, the UK’s coal power phaseout – as well as the closure of some of the country’s few remaining blast furnaces at Port Talbot in Wales and Scunthorpe in Lincolnshire – will help push overall coal demand in 2024 to its lowest level since the 1600s.

In total, coal-fired power stations in the UK will have burned through some 4.6bn tonnes of coal across 142 years, generating 10.4bn tonnes of CO2, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

If UK coal plants were a country, they would have the 28th-largest cumulative fossil-fuel emissions in the world. This would mean greater historical responsibility for current climate change from those coal plants than the likes of entire nations such as Argentina, Vietnam, Pakistan or Nigeria.

The UK’s electricity system today looks dramatically different to even just a few decades ago, with renewables increasingly dominating the generation mix.

In 2023, renewables set a new record by providing 44% of the country’s electricity supplies, up from 31% in 2018 and just 7% in 2010. Their output is set to increase from around 135TWh in 2023 to more than 150TWh this year, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

By comparison, fossil fuels made up just a third of supplies, with a record-low 33% of the electricity mix, of which coal was a touch over 1%.

This decrease of just under 20% brought fossil fuel supplies down to 104TWh, the lowest level since 1957, when 95% of the mix came from coal.

The changing makeup of the UK’s electricity mix over the past century is shown in the figure below. Notably, while oil, nuclear and gas have each played important roles in squeezing out coal power, it is now renewables that are doing the heavy lifting.

Indeed, all other sources of generation are now in decline: nuclear as the UK’s ageing fleet of reactors reaches the end of its life; and gas, as well as coal, as renewables expand.

In 2024, renewables have continued to take up an increasing share of the electricity mix, with Carbon Brief analysis of year-to-date figures putting them on track to make up around 50% of supplies for the first time ever.

The growth of renewable electricity in the UK’s electricity mix has been “instrumental in driving coal out”, E3G’s Rae-Roche tells Carbon Brief:

“Crucially, coal hasn’t been replaced by other fossil fuels, gas generation fell from 46% in 2010 to 32% in 2023. [Carbon Brief analysis suggests gas will fall again, to around 22% of electricity supplies in 2024.] So, on a gigawatt basis, we’ve replaced the ‘firm’ coal capacity with gas, but on a gigawatt hour basis – which is what matters to emissions – we stopped using as much [of either] coal or gas because of the renewables on the system.”

For one hour in April, for example, the share of electricity coming from coal and gas fell to a record-low 2.4%, Carbon Brief analysis revealed.

This pressages the first-ever period of “zero-carbon operation”, when the electricity system will be run without any fossil fuels – a moment that the National Energy System Operator (NESO) expects to reach during at least one half-hour period during 2025.

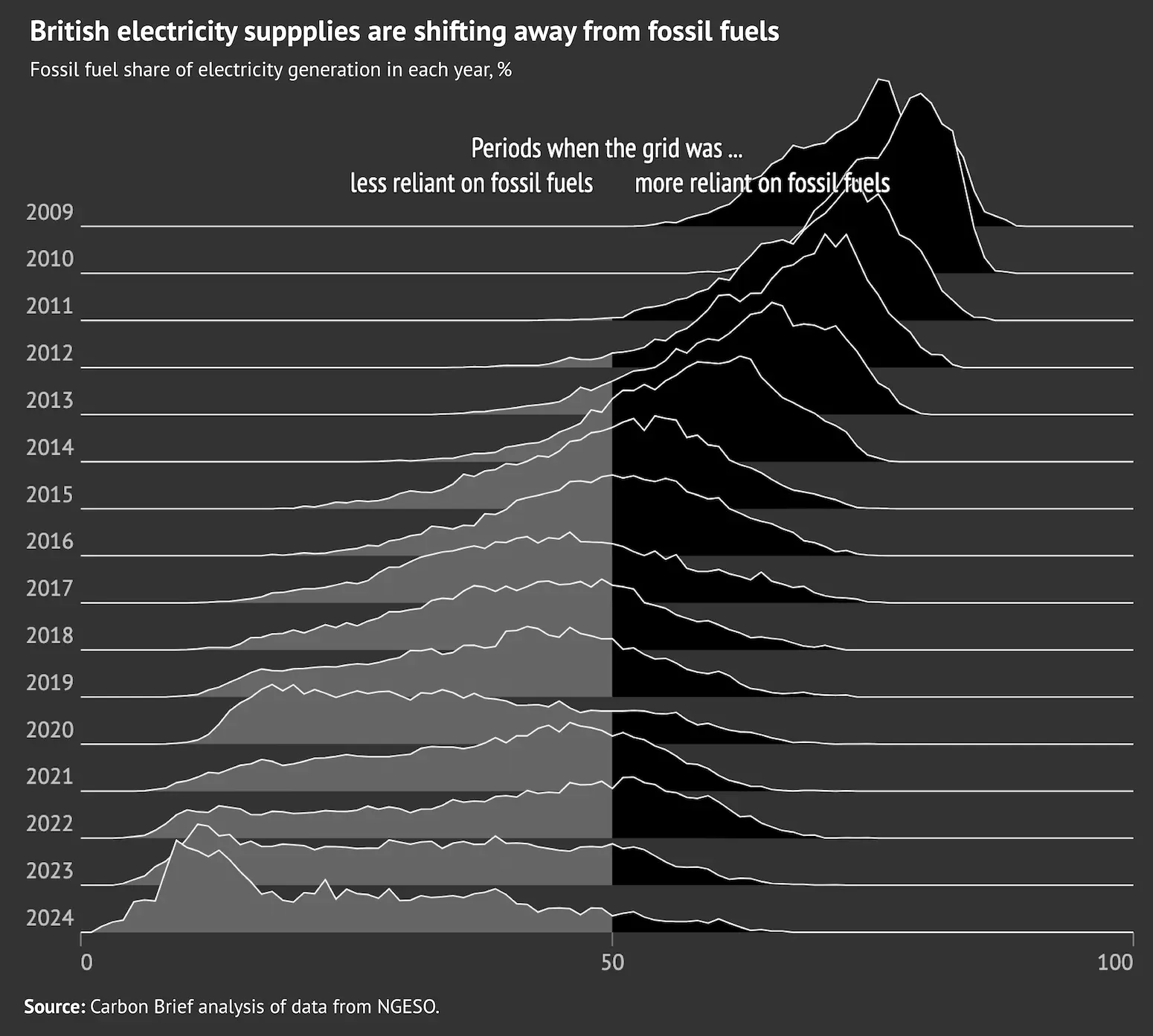

In 2009, the lowest half-hourly fossil-fuel share was 53%. The first half-hour period where there was less than 5% fossil fuels only happened in 2022, Carbon Brief’s analysis found.

Last year, there were 16 half-hour periods with less than 5% fossil fuels and more than 75 periods of such in the first four months of this year.

This switch has been enabled by the swift growth of renewable technologies, in particular wind, which now vies with gas month-to-month as to the biggest source of electricity in the country. In the first quarter of 2024, wind contributed more electricity than gas generation for the second quarter in a row.

After becoming the first major economy to phase out coal generation, the UK is looking to go one step further by fully decarbonising its power supplies by 2030.

Under the previous Conservative government, the UK was targeting a fully decarbonised power sector by 2035. The newly elected Labour government brought this forward to 2030.

At the same time, the power sector will need to start expanding in order to meet demand from sectors such as transport and heating, as they are increasingly electrified.

Former Climate Change Committee (CCC) chief executive and now head of “mission control” for the government’s 2030 power target Chris Stark told a central London event in mid-September that he saw the goal as “possible”, but “challenging in the extreme”.

Noting scepticism that clean power by 2030 is achievable, he said that it was nevertheless a real goal and not an aspirational “stretch target”.

Stark added that many people had been similarly sceptical of the UK’s ability to phase out coal power by this year – and that that scepticism “really motivates me”.

Electricity demand in the UK is expected to increase by 50% by 2035, according to the CCC.

Meeting this growth at the same time as phasing out unabated gas will require a very large increase in renewable generating capacity, as well as supporting systems to ensure the grid can run securely on predominantly variable generation from wind and solar.

At the event, Stark noted that clean power by 2030 was a “smaller target” than for 2035 because it would come before widespread electrification of heat and transport.

Even so, meeting the goal would require unabated gas power to be phased out within six years, from its current share of around 22%. This would be roughly twice as fast as the UK has phased out coal, from 39% in 2012 to zero in 2024, as the chart below shows.

In order to meet its 2030 target and wider UK climate goals, the Labour government has pledged to double onshore wind capacity, treble solar and quadruple offshore wind.

The expansion of renewables is continuing to be supported by the government’s “contracts for difference” (CfD) scheme. The latest allocation round wrapped up earlier this month and secured contracts for 131 projects, with a total capacity of 9.6GW.

While many welcomed the results as a boost to the renewable pipeline in the UK, others highlighted the need to ramp up capacity in the coming years.

Analysis by trade association Energy UK found that the next CfD auction would need to secure four times more new capacity in order for the UK to reach its targets.

The Labour government is also backing new nuclear projects, CCS and a “strategic reserve of gas power stations” to guarantee security of electricity supplies.

According to a 2023 report from the CCC on how to meet the then-2035 power-sector decarbonisation target, renewables were expected to make up around 70% of generation in 2035, with nuclear and bioenergy contributing another 20% and the final 10% coming from flexible low-carbon sources, including energy storage, CCS or hydrogen turbines.

(A September 2024 report from the International Energy Agency sets out the “proven measures” that can be taken to integrate growing shares of variable wind and solar into electricity grids, while maintaining system stability. It says: “Successful integration maximises the amount of energy that can be sourced securely and affordably, minimises costly system stability measures, and reduces dependency on fossil fuels.”)

Since taking office, the Labour government has asked the Electricity System Operator (ESO, soon to become the National Energy System Operator NESO) to provide “practical advice” on how to reach the “clean power by 2030” target.

Stark told the event that he expected this advice to show that 2030 was unachievable under the current policy and regulatory regime. He said that, by the end of the year, the government would publish a paper setting out the policies that would be needed.

After 142 years of near-continuous electricity generation from coal, the closure of Ratcliffe-on-Soar is truly the end of an era for the UK.

Moreover, there is an obvious symbolism around the UK, home to the world’s first-ever coal-fired power station in 1882, becoming the first major economy to phase out coal power.

Perhaps because of its status as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution and as the world’s first “coal-power economy”, the UK’s coal phaseout is also viewed internationally as an “inspiring example of ambition”, says COP29 president-designate Mukhtar Babayev.

Beyond mere symbolism, the UK’s coal phaseout also matters in substantive terms, because it shows that rapid transitions away from coal power are indeed possible.

Coal’s share of UK electricity generation halved between 1990 and 2000 – and then dropped from two-fifths of supplies in 2012 to zero by the end of 2024.

This progress hints at the potential for other countries – and indeed the whole world – to replicate the UK’s success and, in so doing, making a major contribution to climate action.

Already Belgium, Sweden, Portugal and Austria have phased out coal-powered generation, and increasingly countries around the world are announcing targets to follow-suit. This includes the G7 announcing in May plans to phase out unabated coal by 2035.

The world’s roughly 9,000 coal-fired power plants account for a third of global emissions, notes IEA chief Fatih Birol. And pathways that limit global warming to 1.5C or 2C include very rapid reductions in CO2 emissions from coal overall – and coal-fired power, in particular.

Indeed, unabated coal-fired power stations have been singled out for attention by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IEA and the UN.

Despite this attention, some 604GW of new coal power capacity is still under development, with the vast majority located in just a handful of countries, including China and India.

In developed countries, three-quarters of coal-fired power plants are on track to retire by 2030, according to the Powering Past Coal Alliance (PPCA). But, globally, 75% of operating coal capacity still lacks a closure commitment, it says.

As other countries look to retire their coal fleets and move away from the fuel, the UK can be used as a case study of a successful phaseout.

There are four key elements that enabled the UK phaseout:

Illustrating each of these elements in turn, on the first point, alternative sources of electricity generation in the UK were initially insufficient to cut into coal power output.

Oil and nuclear from the 1950s onwards eroded coal’s share of electricity generation, but were not sufficient to meet rising demand, meaning coal output kept growing.

In contrast, gas power plants were built so rapidly in the 1990s that they exceeded demand growth and pushed coal generation into decline. Similarly, the rapid growth of renewables after 2010, combined with declining demand, was key to the UK’s coal phaseout.

On the second point, the UK did not build any new coal plants after 1986, partly as a result of protests and political action in the 2010s.

Speaking to Carbon Brief Daniel Therkelsen, campaign manager at campaign group Coal Action Network, says the end of coal-fired power was a “historic moment”, adding that it was “a huge win for the UK public…particularly [those] who spent countless hours campaigning”.

The fact that the UK did not build new coal plants meant there were no recently built assets – with associated economic interests – needing to be retired early for a phaseout.

Moreover, the UK’s existing coal-power fleet was reaching the end of its economic lifetime.

The fact that there were few UK coal mining jobs remaining after the 1980s removed another interest group, that might have stood in the way of the coal power phase out. (In contrast, “influential…coal corporations and unions” have slowed coal’s decline in Germany.)

In terms of externalities, a series of UK and EU policies and regulations covering air pollution and carbon pricing helped tip the scales against coal power.

By making coal plants pay for pollution control equipment, CCS infrastructure or CO2 emissions permits if they wanted to stay open, these policies changed the economic calculus in favour of alternative sources of electricity generation.

Finally, the UK government’s 2015 pledge to phase out unabated coal sent a clear signal to the electricity sector. It allowed decision-making to proceed in the full knowledge that coal plants would need to close, that plant operators would need to diversify their portfolios rather than investing in continued coal-plant operation, and that the sector as a whole would need to ensure alternatives were in place to maintain reliable electricity supplies.

E3G’s Rae-Roche highlights the long-term political goal of coal phaseout as the starting point for successful implementation. He explains:

“You need to set long-term goals and have policy stability about where you want to get to from there. Once you’ve got that established, you think about the legislation that’s required to incentivise clean and move away from fossils. What support needs to be delivered to the clean industry, how that support needs to be managed in terms of the power system and what the power system needs to actually deliver it.”

Similarly, Frankie Mayo, senior energy and climate analyst at Ember, tells Carbon Brief that clear political commitment and policies are key. He says:

“The biggest lesson is that, once the commitments and policies are clear, then rapid, large-scale clean power transition is possible, and it lays the groundwork for future economy-wide decarbonisation.”

As the UK embarks on its next major challenge in the power sector – targeting clean power by 2030 – it has another opportunity to provide a successful climate case study to the world.

Data analysis by Verner Viisainen.

Graphics and design by Joe Goodman.

HYDROGEN: Uncertainty surrounding federal tax credit rules has left the clean hydrogen industry stuck in neutral, but experts say the delay is providing much-needed time to figure out the best uses for the fuel. (Canary Media)

ALSO: General Motors plans to partner with a large supplier to build a hydrogen fuel cell plant in Detroit, which could take a few years until production starts. (Crain’s Detroit, subscription)

OIL & GAS:

ELECTRIC VEHICLES:

UTILITIES: Advocates sound the alarm over a lack of policies stopping utilities from shutting off customers’ power for nonpayment during deadly heat waves. (The Guardian)

GRID:

NUCLEAR: The U.S. Energy Department greenlights California startup Oklo’s plan to begin developing an advanced nuclear reactor at the Idaho National Laboratory. (Newsweek)

POLITICS: Environmentalists push back against a bill that would weaken semiconductor industry oversight that President Biden is reportedly set to sign. (The Hill)

PIPELINES: A planned 645-mile pipeline across Texas from the Permian Basin to a Louisiana terminal creates landowner concerns about its effects on nearly 13,000 acres of land, including the possibility of eminent domain. (KOSA)

MINING: Arkansas sees a rush to mine lithium for batteries, triggering memories of unscrupulous and shady behavior during a previous oil boom and raising concerns about the ephemeral nature of extraction. (Grist)

COMMENTARY: Federal support for carbon capture and storage relies on the assumption that unproven and prohibitively expensive technologies will soon become viable, an energy analyst writes. (Utility Dive)