Rye Development secured a federal license to build a massive new pumped hydro energy storage facility in Washington state. The company could become the first to construct this type of grid megaproject in the U.S. since 1995.

Long before lithium-ion batteries reshaped the power sector, utilities stored electricity by pumping water uphill when energy was abundant and later letting it descend, turning turbines to generate power when needed. This technique depends on gravity and heavy construction, and the U.S. pumped hydro fleet got built when utilities could unilaterally invest in long-term assets. In the country’s modern, largely deregulated, and rapidly changing power markets, nobody has pulled off the expensive and time-consuming feat.

Until now — potentially. On Thursday, Rye secured a license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to build and operate a planned pumped storage project just north of the Columbia River Gorge, near the town of Goldendale (population 3,500). It’s the final regulatory step, meaning that Rye can now finalize plans and begin building.

“With electricity demand and energy costs on the rise, this type of pumped storage project represents a huge step forward,” said Erik Steimle, director of development at Rye. He added, “It’s a fully domestic source of energy storage: The major components are concrete, steel, and labor.”

That effort joins two others Rye is working on, which Steimle said could start construction sooner: Swan Lake in Oregon and Lewis Ridge in Kentucky. So far, though, none have broken ground.

At Goldendale, Rye plans to excavate two 60-acre reservoirs separated by 2,000 feet of vertical gain. The company will pipe in water from the nearby Columbia River, then circulate the water up and down to store and discharge power.

This will have a nameplate capacity of 1.2 gigawatts, bigger than any battery storage installation thus far. But pumped storage really shines in how long it can discharge power for — in this case, 12 hours. The cost of building a bigger reservoir scales much more favorably than stacking more batteries does to achieve the extended storage.

The project is a bet on increased demand for long-duration storage as intermittent renewable production surges. The Pacific Northwest has built ample solar and wind generation but has struggled to expand its transmission network, which produces congestion on the wires. So a major storage plant like Goldendale could help: charging up when solar or wind floods the network and then discharging back when demand is high.

The project will typically pump water for 12 to 16 hours a day and generate eight hours a day, but it could push that to a maximum of 12 hours, according to the license document.

Individual power plants seldom need to petition FERC for permission, but Goldendale fell under that body’s jurisdiction because it will connect with federal land and pump water from a navigable waterway. Notably, the new reservoirs will not even touch the Columbia, drastically limiting environmental impacts, compared with those from America’s earlier dam-building spree.

The layout covers about 680 acres, largely private land that used to house a decommissioned aluminum smelter, but it connects to transmission infrastructure overseen by the federal Bonneville Power Administration. Up on a ridge, the high reservoir will be nestled among a series of wind turbines. Between that power plant and the smelter, Rye won’t need to build any new access roads, Steimle said.

The approval stipulates certain environmental mitigations: Rye has to schedule its filling of the reservoirs to avoid altering the river flow during salmon smolt migration, for instance; plant native vegetation on disturbed land; and purchase 277 acres elsewhere to dedicate to golden eagles’ nesting and foraging.

With federal permission secured, Rye now needs to lock down customer contracts (much like another capital-intensive long-duration storage project, Hydrostor’s recently approved compressed-air effort in California). This type of infrastructure is too costly to build without a guarantee of revenue. But Rye needed to win its license before it could finalize contracts with customers, Steimle noted. The project can serve utilities in the Pacific Northwest as well as in California, where state regulators have mandated that power providers buy long-duration storage to balance a massive supply of solar generation.

Rye has already secured a financing partner for Goldendale: Danish firm Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, which also bought Rye’s Swan Lake project, back in 2020. Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners will supply the estimated $2 billion to $3 billion needed to build Goldendale once Rye finds buyers for the clean power.

Now, Rye will finalize construction planning alongside its commercial efforts. The FERC license stipulates that construction must commence within 24 months, so the countdown is on.

Even Rye’s successful licensing journey underscores the challenges of leaning on pumped hydro to support the transition to clean energy. The company filed for its license in June 2020. It took five and a half years to get the green light, and it will take up to two years to finalize plans and then four or five more to actually finish building the thing.

That ponderous pace explains why such a large-scale plant hasn’t been built in the U.S. since the Rocky Mountain Hydroelectric Plant came online in Georgia in 1995. A few other companies have tried, like Absaroka Energy, which is developing the Gordon Butte plant in Montana. Globally, a new pumped hydro site opened in Switzerland in 2022; it took just 14 years.

To put it simply, pumped hydro construction isn’t a nimble response to a rapidly changing electricity mix. Batteries, on the other hand, are — they’re mass-produced in factories and can be installed swiftly in prepackaged containers.

But pumped hydro works extremely well when built. It has a far longer duration than the typical four-hour lithium-ion battery. These facilities also last far longer than lithium-ion cells, which degrade with use. The Goldendale license covers 40 years of operation, but the system is designed to last 100, Steimle said; the owner of the Rocky Mountain plant sought a license extension for another 40 to 50 years.

“Pumped hydro is a battery you can cycle over and over again with little to no degradation over a very long period of time,” he said.

And it clearly works at a massive scale: The U.S. has more than 22 gigawatts already running.

As Paul Denholm, a clean grid modeler at the institution formerly known as the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, told Canary Media previously, “Utilities with pumped-storage plants love them — they’re awesome.”

For nearly two years, Century Aluminum has been searching for a site to put a giant new U.S. smelter — a decision that largely hinged on where it could strike a deal with utilities to access cheap, reliable electricity.

On Monday, the Chicago-based manufacturer finally unveiled its plans. Rather than build its own power-hungry facility, Century is partnering with Emirates Global Aluminium to jointly develop a smelter near Tulsa, Oklahoma, the companies announced. The facility will be America’s first new aluminum smelter in nearly half a century if completed as planned by the end of the decade.

“Together we will make a huge contribution to rebuilding American aluminum production for the 21st century,” Abdulnasser Bin Kalban, CEO of the Dubai–based EGA, said in a statement.

Century had previously identified northeastern Kentucky as its preferred location for a $5 billion smelter, though the company was also evaluating sites in the Ohio and Mississippi river basins. In 2024, the Biden-era Department of Energy selected Century to receive up to $500 million to build a “green” smelter powered by 100% renewable or nuclear energy.

Century didn’t immediately return Canary Media’s questions about the status of the federal award or how energy issues factored into its decision to join forces with EGA.

But on Tuesday, Century CEO Jesse Gary told Fox Business, “That grant is going to underlie the total investment … to help build this new smelter.”

Aluminum production contributes about 2% of greenhouse gas emissions globally every year, and the majority of those emissions come from generating high volumes of electricity — often derived from fossil fuels — to power smelters.

Emirates Global Aluminium first proposed building its own Oklahoma smelter last May. Up until this week, EGA and Century seemed to be racing each other to fire up their new facilities. The fact that the companies teamed up reflects how difficult it is for manufacturers to secure power at the volumes and prices they need, not only in the United States but globally — a challenge that’s getting even harder with the competition from AI data centers.

Building a smelter “is very expensive and very complicated, so I take it as good news,” said Joe Quinn, who leads the Center for Strategic Industrial Materials for SAFE, which advocates for policies to enhance U.S. energy security.

“There was a scenario where both could have failed,” he added. “But now they’re getting together, and I think that strengthens the likelihood of a new smelter being built in the United States.” He said the news was “a little surprising, but then again not that surprising” given the challenges of opening a multibillion-dollar greenfield smelter.

Under this new agreement, EGA will own 60% of the joint venture and Century will own the remaining 40%. The Tulsa-area facility is expected to produce 750,000 metric tons of aluminum per year, an amount that is 25% larger than previously envisioned — and more than double the current U.S. production of primary aluminum.

A facility that massive will require over 11 terawatt-hours of power, or enough electricity annually to power the city of Boston or Nashville, according to an Aluminum Association report.

America’s output of the versatile metal has sharply declined in recent decades, in large part owing to rising industrial electricity rates. Today, the country operates just four smelters — down from 33 in 1980 — and it imports about 85% of all the aluminum it needs each year. At the same time, the U.S. is using more aluminum in solar panels, power cables, infrastructure, and electronics. By 2035, U.S. demand for primary aluminum is expected to rise by as much as 40%, the advocacy group Industrious Labs said in a report last year.

Annie Sartor, Industrious Labs’ senior campaigns director, said that “two smelters would have been ideal” for boosting U.S. aluminum production. “One is better than none, but neither can succeed without affordable, clean power,” she said in a statement.

Construction on the Oklahoma smelter is set to start by the end of this year, the companies said. Negotiations are still underway with the Public Service Company of Oklahoma, which is a subsidiary of utility giant AEP, and the state of Oklahoma to secure a competitive, long-term power contract.

Last year, EGA signed a nonbinding agreement to build its proposed smelter with the office of Republican Gov. J. Kevin Stitt, a deal that includes over $275 million in incentives, including discounts for power. Oklahoma’s “energy abundance” was a key factor in selecting the state for the new aluminum smelter, Simon Buerk, EGA’s senior vice president for corporate affairs, previously told Canary Media.

More than 40% of Oklahoma’s annual electricity generation comes from wind turbines spinning on open prairies, while about half the state’s generation comes from fossil-gas power plants. Last summer, the Public Service Company acquired an existing 795-megawatt gas plant south of Tulsa to meet the rising energy needs of its customers, potentially including EGA.

Buerk said last year that the Oklahoma smelter’s annual power mix “will be based on EGA’s decarbonisation objectives, market dynamics, and market demand for low-carbon aluminum.” He confirmed that Monday’s announcement doesn’t change any of the options being discussed in ongoing negotiations with the utility. That includes a potential tariff structure that gives the smelter dedicated long-term access to a proportion of renewable energy.

The news that Century Aluminum is investing in Oklahoma comes as a major letdown for some environmental and labor groups in Kentucky, who had advocated for bringing the project to their state. Century already owns two aging smelters in western Kentucky, and the new facility was supposed to create thousands of construction jobs and more than 1,000 permanent positions — jobs that will now go to Oklahoma.

“This is a disappointing loss for Kentucky, but it should serve as a wake-up call,” Lane Boldman, executive director at Kentucky Conservation Committee, said in a statement. “For Kentucky to remain an energy leader and meet the needs of industries looking for reliable and affordable power, it must modernize its energy infrastructure more quickly, such as grid modernization, energy storage, and diversifying with renewables.”

An update was made on Jan. 27, 2026 to include a response from EGA and comments from Century CEO Jesse Gary.

U.S. solar manufacturers start 2026 in an odd position. They have made real strides toward reshoring production, but still have a long way to go — and federal and trade policies are layering new uncertainties onto the task.

The U.S. is now actively producing all the major components in the solar supply chain: polysilicon, ingots, wafers, cells, and modules. That hasn’t happened in over a decade, since SolarWorld closed its wafer-production plant in Oregon in 2013.

“Except for the glass, everything we have in the module could be domestic, should the client choose that,” said Martin Pochtaruk, CEO of Heliene Solar, which manufactures in Minnesota. “The main issue is the limitation on capacity.”

The U.S. can make almost 65 gigawatts of panels annually, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. But it can’t yet build enough of the precursor components to meet the demand for panels. (SEIA expects the U.S. will install 44 gigawatts of direct-current solar capacity this year.)

Major factory construction now underway takes aim at that shortfall, even as factory owners grapple with upheavals in federal domestic and trade policies.

Congress created new rules last year that block tax credits from going to “foreign entities of concern,” or FEOC. Those regulations technically kicked in on Jan. 1, but the Treasury Department still needs to release preliminary guidance and launch formal rulemaking.

Separately, an anti-dumping investigation could raise tariffs on solar imports from India, Indonesia, and Laos, as part of a long-running Commerce Department effort to block imports by China-linked companies that build in other countries to avoid steep tariffs.

And last year, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick launched an investigation into the national security implications of the polysilicon supply chain, which could impose global tariffs on products that contain polysilicon — including solar panels and their components.

Here are the three biggest storylines to follow for the state of domestic solar manufacturing in 2026.

As of last year, U.S. factories have officially been able to make enough solar modules to meet domestic demand.

Cell capacity, however, lags far behind, at just 3.2 gigawatts. This year, companies are pushing to catch up.

“If we want to have the manufacturing here, we have to have the cell manufacturing here, because that’s the most difficult step, in many ways; it’s where a lot of the innovation happens,” said Tim Brightbill, a lawyer at Wiley Rein LLP who has brought numerous trade cases on behalf of domestic manufacturers. “We can’t just outsource that to China and hope the rest of the industry will be OK.”

Newcomer T1 Energy started building its cell factory in December in Rockdale, Texas, and should open 2.1 gigawatts of cell production by year’s end.

“This is the year of execution for us,” said Russell Gold, T1’s executive vice president for strategic communications. The 100-acre facility will cost $400 million to build and will generate 1,800 jobs. A planned second phase would add another 3.2 gigawatts.

Qcells, the subsidiary of Korean conglomerate Hanwha, is still plugging away on its ingot, wafer, and cell factory in Cartersville, Georgia. The site started producing modules in 2024; it was supposed to produce ingots, wafers, and cells — the more complicated precursor steps — in 2025, but that build-out fell behind schedule. Qcells is aiming to get Cartersville fully operational by the end of 2026, said Marta Stoepker, head of corporate communications at Qcells North America.

Norway’s NorSun had planned a $620 million, 5-gigawatt ingot and wafer factory near Tulsa, Oklahoma, set to open in mid-2026 and supply Heliene and others. But the company’s website returns a 404 error code, and NorSun told Heliene that the Tulsa factory is not moving ahead, Pochtaruk said.

Heliene had wanted to build a cell factory to supply its 1.3-gigawatt module production in Minnesota, but it froze development amid the market turbulence when President Donald Trump took office in 2025. In the coming weeks, Pochtaruk said, Heliene will begin large-scale production of panels using Suniva cells made with domestic wafers, supplied by Corning, which are sliced from domestic polysilicon created by Hemlock Semiconductor in Michigan.

Then there’s an important outlier: First Solar, which has long been the only solar manufacturer with a homegrown supply chain.

First Solar is also unique in that it eschews silicon in favor of thin-film deposition of cadmium and telluride. It’s able to produce a fully functioning solar panel without the separate steps of carving wafers or etching silicon cells. That advantage allowed the company to grow and thrive behind protective U.S. tariffs in the years when the silicon-solar industry collapsed.

First Solar has built 14 gigawatts of domestic manufacturing capacity across Alabama, Louisiana, and Ohio and is building a new site in South Carolina.

The Republican budget law passed last year forces companies that want to claim the solar manufacturing tax credit, or tax credits for installing solar panels, to prove that they aren’t overly beholden to control or support from prohibited Chinese entities.

Weaning any high-tech supply chain from Chinese influence is challenging, but the task is further complicated because the federal government hasn’t finalized its rules yet. In theory, any panel coming off the line since New Year’s Day needs to comply, but doing so requires a bit of extrapolation, or perhaps luck.

Some companies should have no problems. Heliene is headquartered in Canada. Qcells hails from Korea. First Solar is homegrown. Still, they need to pay for the legalistic accounting to prove they qualify.

Some manufacturers that had ties to China, however, have taken steps to reverse that status. China’s JA Solar sold its Arizona factory to Corning. Trina Solar sold its Dallas factory in 2024 to the company that became T1; in December, T1 released a detailed breakdown of the steps the U.S.-headquartered company took to clear itself of FEOC-related risk.

“We want to show investors, hey, we’re prepared for this, we did our work,” Gold said.

Others have slightly more complicated arrangements, like Canadian Solar, which, despite its name, operates largely out of China; and Illuminate USA in Ohio, a joint venture between U.S. developer Invenergy and Chinese solar giant Longi. These firms have not yet completed the kind of sell-off that Trina did with T1, so it’s harder to see how their 2026 production could qualify for tax credits.

In another category are clearly Chinese-owned factories in the U.S., including JinkoSolar in Florida and Hounen Solar in South Carolina, which seem sure to fail the FEOC test.

The quest for FEOC compliance will be a dominant theme for the industry this year — especially once the rules are actually released.

U.S. solar manufacturing has long depended on trade protections, and two major proceedings could reshape the global playing field this year.

Historically, the U.S. has levied tariffs on China’s solar exports in order to offset government subsidies that helped drastically lower the cost of panels made there. Major Chinese manufacturers responded by building module assembly factories in other countries that did not face such tariffs.

Last year, the U.S. added tariffs on solar modules from Cambodia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Vietnam after concluding a Biden-era trade case.

A subsequent petition by U.S. manufacturers could extend tariffs to India, Indonesia, and Laos. Such requests used to draw an outcry from solar developers, who would face higher prices for their materials. But last year, at the U.S. International Trade Commission’s preliminary hearing for the latest case, nobody testified in opposition, Brightbill said, though some parties later filed opposing statements.

The Commerce Department’s investigations could wrap up over the next few months and lead to preliminary duties, with a final determination coming in the early fall.

A different trade action could take a more global approach than this country-by-country effort.

“It’s not only tax credits you have to look into,” Pochtaruk said of planning new factory investments. “Any and all business plans have to have in consideration what the heck the 232 [outcome] is.”

He’s referring to the ongoing investigation into the national security implications of the polysilicon supply chain, under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962. Trump previously used this mechanism to push for tariffs on things like steel and aluminum; it’s different from the authority he invoked for the so-called Liberation Day tariffs last year.

“The courts have largely upheld Section 232 actions by the president, because they tend to defer to the president on national security issues,” Brightbill said.

The Section 232 investigation could produce a far-reaching global tariff on products that contain silicon — not just raw polysilicon but also finished solar cells and panels.

Such a global tariff could drive up costs for the domestic module makers that still have to import cells, since the U.S. is not yet self-sufficient in that step. Then again, it would also raise the cost of foreign modules competing with domestic ones.

“It could be a way to address this Whac-A-Mole problem that we’ve been dealing with for some time,” Brightbill said.

By statute, the Commerce Department must send recommendations to the White House by March 28, which then gives the president 90 days (until late June) to formulate a response.

“All of this contributes to a level of uncertainty around your solar supply chain, and makes building a reliable, transparent, domestic solar supply all the more important,” said Gold, of T1. “The fact that we have a supply deal with Hemlock and Corning gives us a lot of comfort.”

New Hampshire Republicans are attempting to do away with a 50-year-old property tax exemption for households and businesses with solar, contending that the policy forces residents without the clean energy systems to unwittingly subsidize those who have them. Supporters of the exemption, however, say this argument is misleading, insulting, and at odds with New Hampshire’s tradition of letting communities shape their own local governments.

The focus of the debate is a bill proposed in the New Hampshire House this month by Republican Rep. Len Turcotte and several co-sponsors in his party. The measure would repeal a law, established in 1975, that authorizes cities and towns to exempt owners of solar-equipped buildings from paying taxes on whatever value their solar systems add to their property. As of 2024, 153 of the state’s municipalities – roughly two-thirds – had adopted the exemption, one of the only incentives offered in support of residential solar power in the state.

The exemption means that homeowners without solar must pay more property tax to make up for the money not being collected from the “extreme minority” who have solar panels, Turcotte said while presenting his legislation at a hearing of the House Science, Technology, and Energy Committee last week. This “redistribution” of the tax burden is unfair, he said.

The solar property tax exemption is a fairly common policy: Nationally, 36 states offer some version of it. While legislators in many states have targeted pro-solar policies like net metering, property tax exemptions have so far avoided similar attacks. New Hampshire, therefore, could end up as a proving ground for whether this approach can find traction.

New Hampshire does not have a sales tax or an income tax and leans heavily on local property taxes for revenue; its rates are among the highest in the country. That makes changes to property tax policy a particularly sensitive subject. The solar exemption bill has Republicans, who are typically tax averse, walking a fine line between championing what they say is fairness for all and pushing a policy that will inevitably raise taxes for some.

The state authorizes 15 other property tax exemptions — including for elderly residents, veterans, and those with disabilities — but Turcotte’s bill targets only the one for solar.

The exemption is a “local option” policy, meaning cities and towns must opt in through a vote in each municipality. Turcotte, however, doubts the average resident realized that they were signing up to pay more on their own taxes.

“They see a feel-good measure,” he said. “Do they truly understand? I don’t believe they do.”

After Turcotte presented his bill, the remaining speakers — about a dozen clean energy advocates, lawmakers, business leaders, and local solar owners — uniformly opposed his proposal.

Removing the exemption would be an unfair rule change after homeowners invested in solar systems with the understanding they’d be getting a tax break, many argued. Businesses using solar could face a “significant tax increase,” said Natch Greyes, vice president of public policy at New Hampshire’s Business and Industry Association. The change could cost homeowners with solar hundreds of dollars per year while barely reducing the property tax rate for everyone else, others said.

In the town of Hudson, for example, $2.2 million in property value isn’t taxed because of the exemption, out of a tax base of $5.1 billion, its chief assessor James Michaud testified. Removing the exemption would have virtually no effect on the tax rate, he said.

“It’s almost incalculable how small it is,” he said.

Whatever tiny tax shift the exemption creates is worth it, others argued, saying that it provides an incentive for the public good: More solar means lower greenhouse gas emissions and less burden on the grid. Turcotte countered that these broader benefits of solar — many of which have been well documented — are “subjective.”

The question of local control also loomed large in the testimony. In New Hampshire, whose motto is “Live Free or Die,” the right of individual towns to decide on their own rules and regulations has long been a point of pride. Repealing the exemption would mean overriding decisions made by voters. Turcotte’s claim that residents didn’t understand what they were getting into is not only condescending but also just plain wrong, several witnesses said.

“You are essentially, with this bill, substituting your judgment about what is proper at the level of local taxation for that of town meetings and city councils throughout the state,” said Rep. Ned Raynolds, a Democrat, while questioning Turcotte.

The bill now awaits a vote in committee before it can face a floor vote from the full House. It would then advance to the Senate. Republicans control both chambers of the state Legislature and the governor’s office.

But the bill’s opponents hope that lawmakers will heed their arguments and give weight to the mass of voters who have approved the exemption across the state.

“This is the reason two-thirds of the towns have adopted it: They can see it’s a good thing,” testified David Trumble, a solar owner from the town of Weare. “Solar is a good thing.”

In the United States, the Trump administration is waging a relentless war on offshore wind, taking an all-of-government approach to thwarting construction of turbines at sea.

On the other side of the Atlantic, however, 10 European countries have formed an alliance to build out 100 gigawatts of offshore wind power and transform the North Sea into what German Chancellor Friedrich Merz called “the world’s largest clean energy reservoir.”

On Monday, officials from Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, and the United Kingdom met in Hamburg to sign a declaration vowing to collaborate on construction of enough offshore wind capacity to power nearly 150 million households by 2050. The document, dubbed the Hamburg Declaration, affirms a goal of building a total of 300 gigawatts of offshore wind capacity in the region, although only a third of that would come from international projects that involve cross-border collaboration. The remaining two-thirds would come from national projects built by countries to send power to their own grids.

At least 100 companies signed onto an accompanying industry declaration in which they promise to cut the costs of offshore wind installations and hire upward of 91,000 workers.

“This is a move not just to establish European energy independence, but to support a strategic sector that’s had a very difficult few years,” said Ollie Metcalfe, the head of wind research at the consultancy BloombergNEF.

Europe has faced energy shortages since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, forcing Kyiv’s allies to wean themselves off the cheap natural gas the Kremlin had shipped westward for decades. The continent ramped up imports of American liquefied natural gas, but that proved very expensive and has left Europe vulnerable to the Trump administration’s bullying on issues such as Greenland’s sovereignty. Nuclear power produces roughly one-quarter of Europe’s electricity, but building new reactors can take well over a decade and some countries, including Luxembourg, remain firmly opposed to atomic energy. In cloudy Northern Europe, with its limited solar potential, harnessing the fierce gusts on the North Sea with offshore turbines represents one of the best options to produce large volumes of power.

Implementing the pact will prove harder than signing it. Countries with lower electricity prices are likely to encounter pushback over a cross-border compact with nations whose energy-market policies have driven up rates. Norway boasts relatively low electricity prices thanks to its vast system of hydroelectric dams. Already, exports of Norwegian electricity to the continent, where Germany’s decision to shut down its nuclear power plants helped push its rates to some of the highest levels in the world, have stirred political blowback in the Nordic nation.

“Sometimes the technical stuff sounds like the most difficult to overcome, but in reality it’s the political and regulatory barriers that end up being the most difficult to solve,” Metcalfe said.

Norway may contribute the fewest turbines under the pact, BloombergNEF forecasts, because its continental shelf drops sharply into deep water, making it difficult to site traditional turbines bolted to the seafloor. Norway has experimented with floating turbines, but the technology is much less mature. And the country’s offshore energy industry has traditionally focused on oil and gas. (Landlocked Luxembourg, which lacks a shoreline, is contributing financing to the deal.)

Europe’s homegrown offshore wind giants, such as Norway’s Equinor and Denmark’s Ørsted, are likely vendors for the buildout, said Gaurav Purohit, the Germany-based vice president of European asset finance at the credit-ratings agency Morningstar DBRS. With the U.S. government bearing down on projects such as Ørsted’s Revolution Wind in New England and Equinor’s Empire Wind in New York, he said the North Sea buildout would allow the companies to redirect capital back to Europe.

Other likely winners of the offshore wind push include the German utility RWE, German transmission giants TenneT and Amprion, and the French energy giant TotalEnergies, which has committed to a big renewables buildout — a contrarian move among oil majors. While China’s soaring offshore wind companies are looking to enter the European market, “I do think European developers will benefit more,” Purohit said.

But he cautioned that the high cost of building offshore wind, particularly when interest rates are elevated and inflation is driving up the price of materials, means that projects would likely “need financial institutions to take a stake.”

Increasing the transmission connections is key, said Matt Kennedy, an executive who heads up sustainability issues for IDA Ireland, the government agency that attracts foreign investment. Right now, the island nation on the EU’s western fringe is connected to other grid systems only by power lines to the United Kingdom. In 2028, the Celtic Interconnector, a 700-megawatt power line connecting Ireland to France, is set to come online, establishing the first direct transmission between the Emerald Isle and the continent. Kennedy said the two-way line will likely hasten construction of offshore wind in Ireland, where the industry has been stunted by planning bottlenecks and, like Norway, a steep continental shelf dropoff. Ireland, which already has a large onshore wind industry, has 7 gigawatts of offshore turbines approved.

Establishing a link to France “really sets the pace for us to be able to deliver on our commitment,” Kennedy said.

“This is a radical step,” he added. “It’s a massive step for Ireland in terms of providing that enabling architecture to access the European market. This will allow us to export an abundance of renewable energy that we plan to have, but also in times of need allows us to import.”

The pact is not renewable energy for the sake of going green, said Ed Miliband, the British secretary of state for energy security and net zero.

“Our view on offshore wind energy is hard-headed, not soft-hearted,” he said, according to Euronews. “I think offshore wind is for winners. Different countries will pursue their national interests, but we are very clear where our interests lie.”

Clean energy foes, from the Trump administration to state legislators to some community members, have long complained that large solar installations are threatening farmland and rural America’s pastoral way of life.

The claims are especially salient in North Carolina, which is both a top-five state for solar deployment and a behemoth in agriculture. Fighting “Big Solar” has become a passionate cause among a small but vocal group of conservatives in this purple state, where lawmakers recently advanced anti-solar legislation dubbed the Farmland Protection Act.

But a new analysis finds that, in actuality, solar fields occupy a tiny fraction of farmland in North Carolina — less than one-third of a percent of the nearly 11 million acres classified as agricultural.

The report by the nonprofit North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, now in its third edition, draws on data from the U.S. Geological Survey, satellite imagery, and state registrations of solar projects with 1 megawatt or more of capacity. The previous version, from 2022, found similar results: Solar that year took up 0.28% of agricultural land.

“A narrative we run into pretty regularly is that solar is taking up a lot of farmland,” said Daniel Pate, director of engagement for the association and a report contributor. But, he said, “the number continues to be minuscule.”

The study comes as Trump officials invoke similar criticisms to stymie large-scale solar, including by kneecapping a program that helps farmers install their own solar arrays.

It also comes as local restrictions on renewable energy, including solar, gain steam around the country.

In North Carolina, a looming threat to solar is the Farmland Protection Act pending in the Republican-controlled state legislature. Sponsored by a longtime solar critic and onetime farmer, Republican Rep. Jimmy Dixon of rural Duplin County, House Bill 729 included a complete ban on large-scale solar on agricultural land when it was filed last April. The provision was later removed, but the bill now phases out county property tax breaks for large solar, a deal-breaker for many developers. With backing from the state Farm Bureau and the state’s agricultural commissioner, the measure has cleared two House committees and awaits a hearing in two more before it can advance to the floor.

Organized opposition, often funded by fossil fuel interests, has unquestionably helped stoke such resistance to renewable energy. But in rural communities, the lingering perception that large-scale solar installations are overtaking the landscape can also come from a place of good faith.

Without doubt, the vast majority of utility-scale solar fields in the state — about 34,000 out of 40,000 acres — are on agricultural land, according to the report. Arrays that have replaced crops and trees are often visible from the road, since that puts them closer to power lines and substations, creating a starker perception of loss. And in some places — especially in wide, flat eastern North Carolina — the concentration of large-scale solar on farmland is substantially higher than the statewide figure. In Halifax County, for instance, solar takes up a full 1% of agricultural land and is on pace to triple its share in the next few years, according to the Center for Energy Education, a local nonprofit.

But despite concerns about its footprint, solar can also help rural communities — to say nothing of its benefits for the climate. Even with the incentives Dixon seeks to abolish, counties are earning vastly more property tax revenue from farmland with solar than from farmland without, researchers say.

Plus, farmers who lease their land for panels have reported earning about $750 to $1,400 per acre per year, according to the report. That steady income can provide a critical supplement to the boom-and-bust revenue inherent in raising crops and animals. That’s one reason Halifax retreated from a proposal last year that would have effectively prohibited new projects: Elected officials heard from constituents who said they would have lost their family farmland but for solar.

Some in the state’s farming community are also enthusiastic about the promise of agrivoltaics, which would allow them to collect revenue from solar while using the land underneath photovoltaic panels for crops, pollinator-friendly plants, or grazing.

Even so, many in the state’s powerful $111 billion agricultural industry remain deeply skeptical of solar. Their distrust is likely exacerbated by decades of bitter battle with environmental advocates — some of the same groups promoting clean energy — over pollution from hog and poultry factory farms.

Jerry Carey, market intelligence specialist for the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association and another contributor to the report, came face-to-face with some of those skeptics when presenting the findings at a recent meeting with “influential farmers.”

“They’re willing to have a conversation. But they don’t want to hear the numbers. They know what they know. They know what they see,” Carey said. As for the dream of agrivoltaics, he added, “One guy literally said, ‘I don’t want to hear about bees and butterflies.’”

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

Two decades ago, the European Union got basically none of its power from wind and solar. Now, those are the leading sources of electricity in the bloc.

In 2025, wind and solar produced more electrons for the EU than fossil fuels did, per a new Ember report — the first time that’s ever happened over the course of an entire year.

It’s a watershed moment. Back in 2015, just under 13% of the EU’s electricity was generated from whirling wind turbine blades and sun-soaking photovoltaic panels. Fossil fuels, meanwhile, produced almost 43% of its power; coal alone accounted for nearly one-quarter of electricity.

Flash forward to 2025: The share of electricity from fossil fuels dropped below 29% while that from wind and solar jumped above 30%.

Though wind still produces more power for the EU than solar does, it was the blistering growth of the latter that drove last year’s achievement. In fact, wind generation actually declined slightly in 2025 from the year prior, but that was offset by a 20% increase in electricity from solar. All 27 EU nations saw solar generation grow last year — and globally, seven EU nations are among the countries that depend most on solar for electricity.

At the same time, coal has entered structural decline, the result of ever-cheaper renewables, an increasing reliance on natural gas, and a suite of policies discouraging coal use. Last year, coal accounted for just 9.2% of the region’s electricity, and several EU nations have already phased it out entirely or committed to doing so before 2030.

That leaves gas, a fuel that provided 16.7% of the EU’s power last year but which the region produces little of.

Europe had heavily depended on gas from Russia until 2022, when the nation invaded Ukraine and prompted a reckoning around domestic energy security in the EU. The bloc is now aiming to quit Russian gas completely by next year. It has turned to two sources to make up for that lost energy: domestic renewables and imported liquefied natural gas from the U.S.

But now, with the Trump administration destabilizing the EU-U.S. relationship, the bloc would like to reduce reliance on the U.S., too. The upshot: Expect renewable energy to keep winning in Europe.

The Double Island Volunteer Fire Department in Yancey County, North Carolina, is the beating heart of this remote community in the shadow of Mount Mitchell, about 50 miles northeast of Asheville. Once home to a schoolhouse that doubled as a church, the red-roofed building still hosts weddings, parties, and other events.

“It was built to serve as a community center,” said Dan Buchanan, whose family has lived in the area since 1747 and whose mother attended the school as a young girl. “A place to gather.”

Sixteen months ago, when Hurricane Helene hit this rugged corner of countryside with catastrophic floods, Double Island’s fire department was where locals turned for help.

“This is [our] ‘downtown,’” said Buchanan, who serves as the assistant fire chief. “In the wake of the storm, people were like, ‘Let’s get to the fire station.’ That was the goal of everybody.”

Fresh out of retirement and living back in his hometown to care for his ailing mother, Buchanan drew on his long career in emergency response to spring into action. With the station, powered by generators, serving as their command center, he and his neighbors gathered and distributed food, water, and other provisions to those in need. They hacked through downed limbs and sent out search teams.

“By the end of the fourth day, we had accounted for all the residents of the Double Island community,” Buchanan said. And while no one in the enclave died because of the hurricane, some suffered while they waited for medications like insulin.

A lack of drinking water and limited forms of communication were also huge obstacles. “When we finally got the roads cleared, and people could get in here, we were literally writing down our needs on a notepad and giving it to whomever, and then they would ferry supplies,” Buchanan said. “A carrier pigeon would have been nice.”

Helene was a “once in 10 lifetimes” storm, Buchanan said, with devastation he and the community hope to never see again. But more extreme weather events are all but certain thanks to climate change, and today Double Island is better prepared.

The station is equipped with a microgrid of 32 solar panels and a pair of four-hour batteries. The donated equipment will shave about $100 off the fire department’s monthly electric bill, meaningful savings for an organization with an annual operating budget of just $51,000.

When storms inevitably hit, felling trees and downing power lines, the self-sustaining microgrid can provide some electricity and an internet signal.

“We’ll have at least a way to run our radio equipment, run our well and basic lighting and refrigeration,” Buchanan said, adding that the latter was vital for medication. “It may not seem like much — but that’s the Willy Wonka golden ticket.”

Communication, he stressed, was key. “If you can’t communicate, you can’t get the help you need.”

The microgrid project, called a resilience hub, was made possible by a network of government and nonprofit groups that came together after Helene to help fire departments like Double Island and other community centers with long-term recovery. Now, a state grant program is injecting a burst of funds into their efforts. Using both public and private time, know-how, and money, the program aims to create a model for resilience that can be replicated nationwide.

“We aren’t only preparing for a disaster; we’re also helping utility diversification, cost savings, and normalization of the technology,” said Jamie Trowbridge, a senior program manager at Footprint Project, a leading nonprofit in the initiative. Those benefits aren’t unique to Yancey County, he said. “We’d like to see this be a pilot for us on what scalable microgrid technology could be across all of western North Carolina — and maybe the country.”

The Double Island experience was common in the immediate aftermath of Helene. Across the region, communities isolated by closed roads and mountainous terrain turned to their fire departments for help.

That’s part of how Kristin Stroup got involved in the resilience hub effort. Based in Black Mountain, a popular tourist destination 15 miles east of Asheville, Stroup helped start a corps of volunteers who gathered at the town’s visitor center. In coordination with an emergency operations center based at Black Mountain’s main fire station, she led over 200 volunteers in doing whatever they could, from cooking and doling out food to making the country roads passable.

“People [were] just driving around the town with chain saws,” said Stroup, today a senior manager in energy and climate resilience with the nonprofit Appalachian Voices. The weekend after Helene hit, she said, “Footprint rolled into town with a bunch of solar panels. I became an instant part of their family.”

With founders who cut their teeth in international aid, the New Orleans–based Footprint Project had teamed up with the North Carolina Sustainable Energy Association, Greentech Renewables Raleigh, and others to pool donations of batteries, solar panels, and other equipment to deploy microgrids to dozens of sites in the region before the end of 2024. From Lake Junaluska to Linville Falls, recipients included fire stations such as the one in Double Island and an art collective in West Asheville.

By February 2025, Footprint had hired Trowbridge and another staff person to work in the area permanently. Footprint continued to cycle microgrid equipment throughout the region from its base of operations in Mars Hill, a tiny college town 20 miles north of Asheville that was virtually untouched by Helene. It launched the WNC Free Store, which donates solar panels and other supplies to residents still far from recovery — like those living out of RVs and school buses after losing their homes.

From the outset, Footprint had a critical local ally in Sara Nichols, the energy and economic development manager at the Land of Sky Regional Council, a local government partnership encompassing four counties that stretch from Tennessee to South Carolina.

“A lot of the other organizations we saw come through in the same way Footprint did, most of them did not stay. They leverage resources to do really important work, and when that work feels done, they go home,” Nichols said. “The fact that Footprint is working thoughtfully to figure out how our recovery and resiliency can be taken care of — while also thinking about their own organizational strategic growth — means a lot to me. They’ve been incredible partners.”

To be sure, assistance and rebuilding in the region are ongoing, and many systemic inequities exacerbated by the storm can’t be solved with a solar panel. But the power is back on. The cell towers are functioning. The roads are open. Piles of debris, from fallen limbs to moldy furniture, have been cleared. In relief parlance, western North Carolina is beginning to see “blue skies.”

That’s why it’s all the more important that Footprint, Appalachian Voices, and other local collaborators haven’t let up in their efforts. The web of organizations involved is thick and, seemingly, ever expanding. Last fall, the network announced it was deploying five resilience hubs around the region, including the Double Island project and a permanent microgrid at a community center in Yancey County.

“These projects, driven by a small group of determined partners, have accelerated Appalachia’s long-term resilience and preparedness,” Invest Appalachia, another nonprofit partner, said in a news release.

Now, the local public-private effort is getting a boost from the state of North Carolina. Under the administration of Gov. Josh Stein, a Democrat who has made Helene recovery a centerpiece of his first-term agenda, the State Energy Office will deploy $5 million from the Biden-era Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to install up to 24 microgrids across six western counties impacted by Helene.

The money will also go to two mobile aid units for rural counties on either end of state — one in the east and one in the west. Dubbed “Beehives” by Footprint, these solar-powered portable units will be full of equipment that can be deployed to purify water, set up temporary microgrids, and otherwise respond to storms and extreme weather.

Expected recipients of the stationary microgrids could include first responders like the Double Island Fire Department and second responders like community centers. Peer-to-peer facilities and small businesses are also encouraged to apply.

Land of Sky and other stakeholders are choosing grantees on a rolling basis through next summer. There’s already been an inundation of applicants, and six grantees have been selected, including a community center about a dozen miles up the road from Double Island in Mitchell County. But organizers say they need more interest from outside the Land of Sky region, especially in Avery County, north of Yancey on the Tennessee border; and Rutherford County, east of Asheville, which includes Chimney Rock, a village that was infamously devastated by Helene and is slowly rebuilding.

Geographic distribution isn’t the only problem organizers have faced. Some entities — while undoubtedly deserving of assistance — aren’t appropriate for the government grant because they are located in areas at risk of future flooding.

“A battery underwater is not that useful,” Trowbridge said, “so if your site is in a floodplain, maybe this isn’t the right fit for you. But we definitely want you to know about the Beehive.”

Above all, organizers like Nichols, a passionate promoter of the Appalachian Region, are determined to ensure that the state’s effort is not the be-all and end-all of resilience.

“What we’re being tasked with as recipients of this money is to try and figure out how we make this a much bigger project,” she said. “That means we’ve brought in other partners like Invest Appalachia. We’ve been seeking other kinds of money. We’re using this state money to successfully build what could be a much more comprehensive resiliency hub model.”

She added that communities across the country — even if they think they’re safe from extreme weather and climate disaster — could take cues from the western North Carolina example.

“We were a place that was not supposed to get a storm,” Nichols said. “We were a climate haven.”

Offshore wind developers are back to building three major U.S. projects nearly a month after the Trump administration ordered them to pause construction.

Ørsted, Equinor, and Dominion Energy all got the green light from federal judges last week to resume work on their massive, multibillion-dollar wind farms off America’s east coast. The companies wasted no time restarting the installation of turbines, offshore substations, and other equipment — eager to make up for delays that had cost each of them millions of dollars a day and threatened to tank at least one project that is more than halfway complete.

The developers had been stuck in limbo since receiving the Dec. 22 suspension order from the U.S. Interior Department, which cited unspecified “reasons of national security” — a rationale that failed to convince federal judges as they weighed developers’ requests for relief. Two other in-progress projects remain mired by delays as they await hearings.

The late-December order was the culmination of the Trump administration’s yearlong assault on offshore wind, which has managed to freeze new development but has been less successful in stopping projects already underway. Most of the five projects are in advanced stages of construction and viewed as critical by grid planners for keeping electricity reliable and affordable. These offshore wind farms are likely the only ones that will get built nationwide in the coming years because of Trump’s interventions.

Dominion Energy, which is developing the Coastal Virginia Offshore Wind project, said it delivered the first batch of turbine components by ship to its leasing area off Virginia Beach, Virginia, last weekend and is now installing the first of its 176 turbines. All the turbine foundations are already in place for the $11.2 billion project, and the utility is working to start producing power in the first quarter of this year.

The wind farm is expected to supply 2.6 gigawatts of clean electricity to the grid when fully completed later this year — power that the region can’t afford to lose, according to the mid-Atlantic grid operator PJM Interconnection.

In a Jan. 13 court brief supporting Dominion Energy, PJM said the offshore wind project would help with the “acute need for new power generation to meet demand” in the 13-state region, much of which is being driven by the boom in AI data centers. “Further delay of the project will cause irreparable harm to the 67 million residents of this region that depend on continued reliable delivery of electricity,” according to PJM’s filing.

Meanwhile, off the coast of Rhode Island, Ørsted has resumed construction on the 704-megawatt Revolution Wind project, which was nearly 90% complete when the federal stop-work order came late last month. The Danish energy giant was hit with a similar order in August, which a federal judge lifted in September given the lack of any “factual findings” by the Trump administration.

Of Revolution Wind’s 65 wind turbines, 58 are already in place, as are the cables and substations needed to bring the power to shore. At the time of the December suspension, the $6.2 billion project had been expected to start generating power as soon as this month, according to Ørsted.

Equinor, which had also previously received a separate stop-work order, is back to work on its 810-MW Empire Wind project off the coast of Long Island, New York.

The developer recently warned that the $5 billion project, which is more than 60% complete, would likely face cancellation if work couldn’t resume by Jan. 16; it won a favorable ruling on Jan. 15. Molly Morris, president of Equinor Renewables America, said the project is using a heavy-lift vessel that is available at the project site only until February, The City reported. After that, Equinor wouldn’t have been able to lease the vessel for another year, creating untenable project delays.

A spokesperson for Equinor said the company now expects to complete work assigned to the vessel, which includes installing an offshore substation, following the injunction ruling.

Continuing construction on America’s offshore wind farms “is good news for stressed power grids on the East Coast,” Hillary Bright, executive director of the advocacy group Turn Forward, said in a statement last week. She added that if projects aren’t allowed to advance, the electricity system in the heavily populated region will be “more likely to experience reliability issues and see ratepayer bills soar.”

Americans’ utility bills are already climbing nationwide, owing in large part to the rising prices and constrained supplies of fossil gas. Residents in colder-climate states are especially feeling the squeeze this winter — though early data shows that existing offshore wind operations are helping reduce electricity costs in some places.

Vineyard Wind, a 800-MW wind farm off the coast of Massachusetts, has been sending power to the grid from 30 of its planned 62 turbines since last October. On Dec. 7, an especially chilly day, the project’s wind output helped displace a significant amount of fossil gas on the wholesale market, resulting in savings of more than $2 million for New England ratepayers over the course of the day, Amanda Barker, the clean energy program manager with Green Energy Consumers Alliance, said on a Jan. 21 press call.

Vineyard Wind is one of the two projects waiting to resume construction in the wake of Interior’s December suspension order. Its developers, Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, sued the federal government on Jan. 15, becoming the last of the affected firms to seek legal relief from the Trump administration’s attacks. Vineyard Wind is now 95% complete, with all but one of its turbines now hovering over the Atlantic Ocean.

The second stalled project, Sunrise Wind, is an Ørsted development off the coast of New York. The 924-MW wind farm is almost 50% complete and, before the stop-work order, was expected to come online in 2026. A court hearing for the development is scheduled for Feb. 2, and the delay is costing Ørsted millions of dollars in the meantime.

Overall, the court orders from last week represent a win for getting more electricity onto the grid during a time of rising demand — and another round of setbacks for Trump’s efforts to destroy the fledgling sector.

Still, it’s hard to say whether this marks the administration’s final attempt to stymie projects or whether more delay tactics are coming for America’s beleaguered offshore wind projects.

See more from Canary Media’s “Chart of the Week” column.

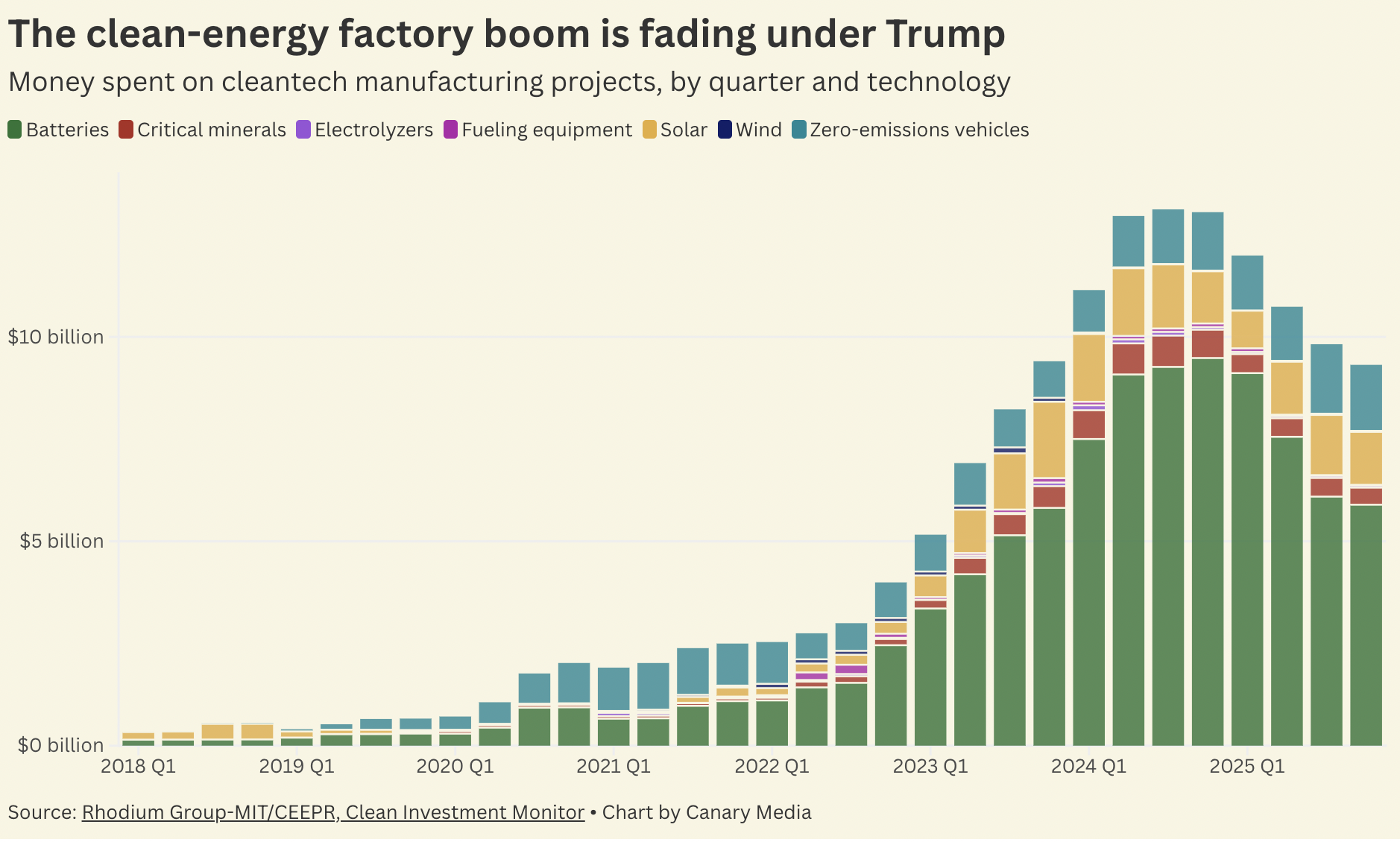

Clean energy manufacturing was on the upswing in the U.S. Then the first year of Trump 2.0 happened.

After years of increasing investment in factories to make batteries, electric vehicles, solar panels, and more — a surge prompted by the Inflation Reduction Act — the trend reversed under the Trump administration last year. Companies spent a total of $41.9 billion on cleantech manufacturing facilities in 2025, down from $50.3 billion the year before, per fresh figures from the Clean Investment Monitor, a joint project from Rhodium Group and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Energy and Environmental Policy Research.

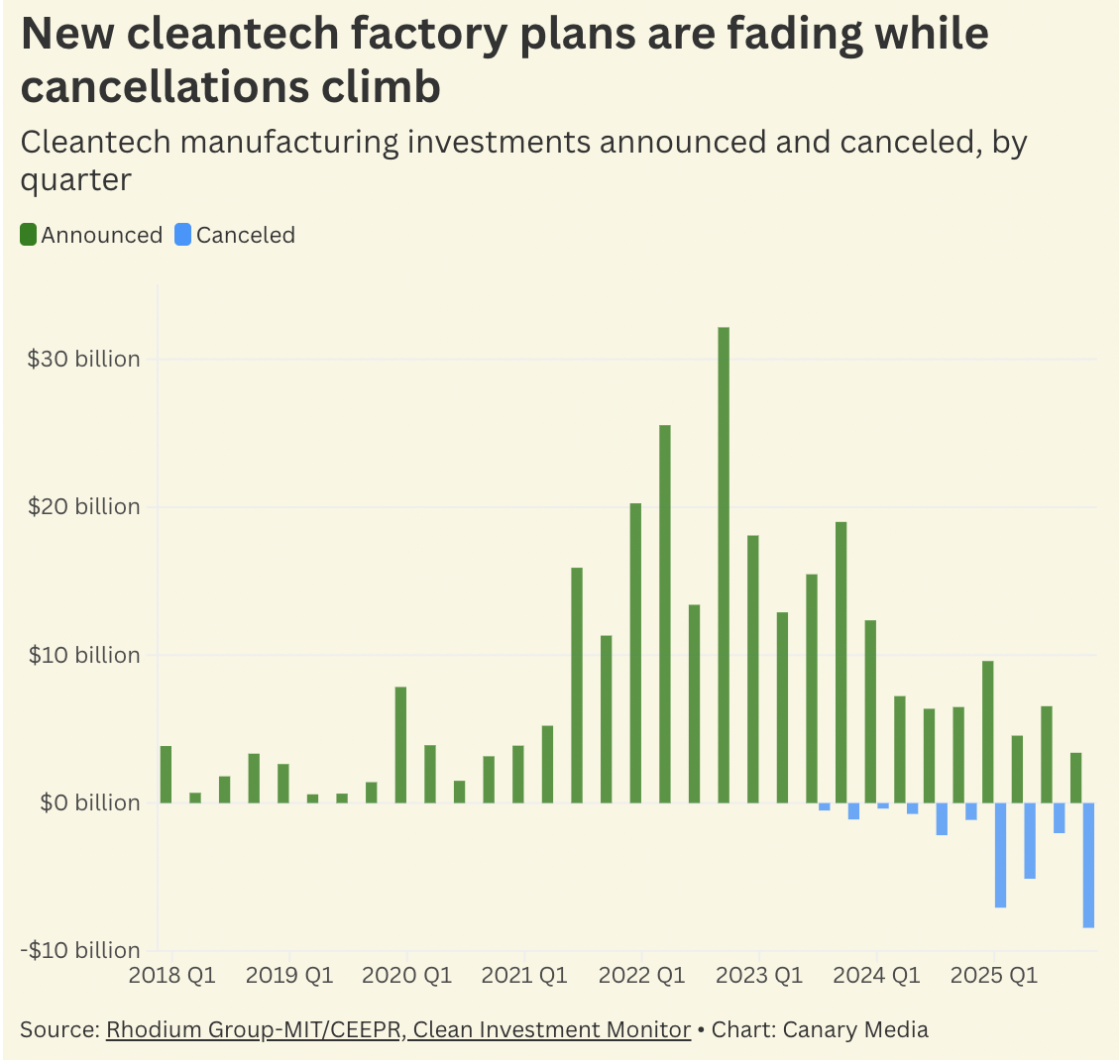

More concerning, however, is the fact that businesses are making fewer new plans to invest in cleantech factories — and a whole lot of companies are backing out of prior commitments.

Cancellations nearly matched factory announcements last year: Firms unveiled a total of $24.1 billion in new cleantech manufacturing projects, but scrapped $22.7 billion worth.

It’s a dramatic reversal. The Biden-era Inflation Reduction Act had spurred well over $100 billion in cleantech manufacturing commitments through incentives for both factories and their customers, be they families in the market for an EV or energy developers building a solar megaproject. The ensuing boom in cleantech factory construction created thousands of jobs and caused overall manufacturing investment to soar. Most of the investment was planned for areas represented by Republicans in Congress.

But last year, the Trump administration put strict stipulations on incentives for factories and repealed many of the tax credits that helped generate demand for American-made cleantech. It also showed an astonishing hostility to clean energy projects — namely offshore wind — and cast a general cloak of uncertainty over the entire economy.

To be fair, other potential factors are at play.

Some of the slowdown in cleantech factory investment could simply be the market maturing. Plenty of projects announced right after the Inflation Reduction Act might already be online, or close to it. Or it could be the result of the gravitational pull of the data center boom, which is attracting gobsmacking amounts of capital that could have otherwise financed more cleantech factories.

But either way, as the new data shows, the Trump administration has weakened the case for investing in expensive projects tied to clean energy. I’m willing to bet that the consequence will be more factory cancellations — and less investment — over this year, too.